A Coral Reef’s Mass Spawning

Understanding how corals reproduce is critical to their survival; Smithsonian’s Nancy Knowlton investigates the annual event

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Nancy-Knowlton-coral-spawning-631.jpg)

It's 9 p.m. and the corals are still not spawning.

Nancy Knowlton and I have been underwater for an hour, diving and snorkeling about 350 feet off the coast of Solarte Island, one of 68 islands and mangrove keys on Panama's Caribbean coast.

Neon-green glow sticks hanging from underwater buoys guide our way. Occasionally, I rise to the surface and hear the thumping bass of Latin music from a coastal town. The moon is full. Surely, this is the perfect setting for a coral love fest.

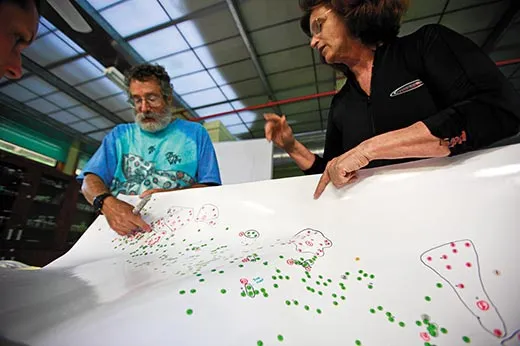

But then I recall what Knowlton had said that morning, standing over a map of her study site: "The coral are fairly predictable, but they don't send us an e-mail."

Knowlton, 60, has studied coral reefs for three decades, first while monitoring the effects of Hurricane Allen, in 1980, on reefs in Jamaica; then as founding director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography's Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation in San Diego; and now as the Smithsonian's Sant Chair of Marine Science at the Natural History Museum. In that time, overfishing has allowed seaweed and algae to grow unchecked, smothering coral worldwide. Poor water quality has increased coral diseases. Deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels have burdened oceans with absorbing more carbon dioxide, which increases their acidity and makes it more difficult for corals to deposit skeletons and build reefs. Currently, a third of all coral species are reportedly at risk of extinction. "If we don't do something," says Knowlton, "we could lose coral reefs as we know them by 2050."

Such grim predictions have earned Knowlton the nickname Dr. Doom. She understands the value of coral reefs—home to one-quarter of all marine species, a source of potential biopharmaceuticals and an organic form of shoreline protection against hurricanes and tsunamis. In the Caribbean, a staggering 80 percent of corals have been destroyed in the past 30 years. Along with other marine scientists, Knowlton has been trying to help reefs survive by better understanding coral reproduction.

For decades, scientists assumed that coral colonies picked up sperm in the water and fertilized eggs internally—and some do. But in the mid-1980s, research biologists discovered that most corals are "broadcast spawners." Unable to self-fertilize, they release sacs containing both eggs and sperm, synchronizing their spawning with neighboring coral colonies. Fertilization takes place in the water. The corals appear to use three cues to begin their mass spawning: the full moon, sunset, which they sense through photoreceptors, and a chemical that allows them to "smell" each other spawning.

Since 2000, Knowlton and a team of research divers have been coming annually to Bocas del Toro, Panama. They have spotted, flagged, mapped and genetically identified more than 400 spawning coral colonies.

The next evening, with no spawning on the first night of this year's expedition, the divers pile into a boat and motor out to the site, about 20 minutes from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute's Bocas del Toro field station. But only a couple of young coral colonies release sacs. "Maybe they're still learning the ropes," Knowlton says.

As with most romantic encounters, timing is everything. The researchers have found that if a coral spawns just 15 minutes out of sync with its neighbors, its chance of reproductive success is greatly reduced. The looming question is, what will happen to fertilization rates as coral colonies become fewer and farther between?

By the third day, the suspense is building. "It will happen," Knowlton barks at lunch, pounding her fists on the table. As her plate rattles, a smile spreads across her face.

Sure enough, the coral colonies start spawning around 8:20 p.m. The tiny tapioca-like sacs, about two millimeters in diameter, rise in unison, slowly drifting to the surface. For the few minutes that they are suspended in the water, I feel like I'm swimming in a snow globe.

"To me, coral spawning is like a total eclipse of the sun," Knowlton says. "You should see it once in your life."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)