After the Tragic Lindbergh Kidnapping, Artist Isamu Noguchi Designed the First Baby Monitor

The six-decade career of the artist and commercial designer is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/22/3e22257a-182e-4ef8-bc2c-e1eb66d5f7ae/radio-nurse-wr.jpg)

It sits like a dark, faceless plastic mask, more like a prototype for a Star Wars film.

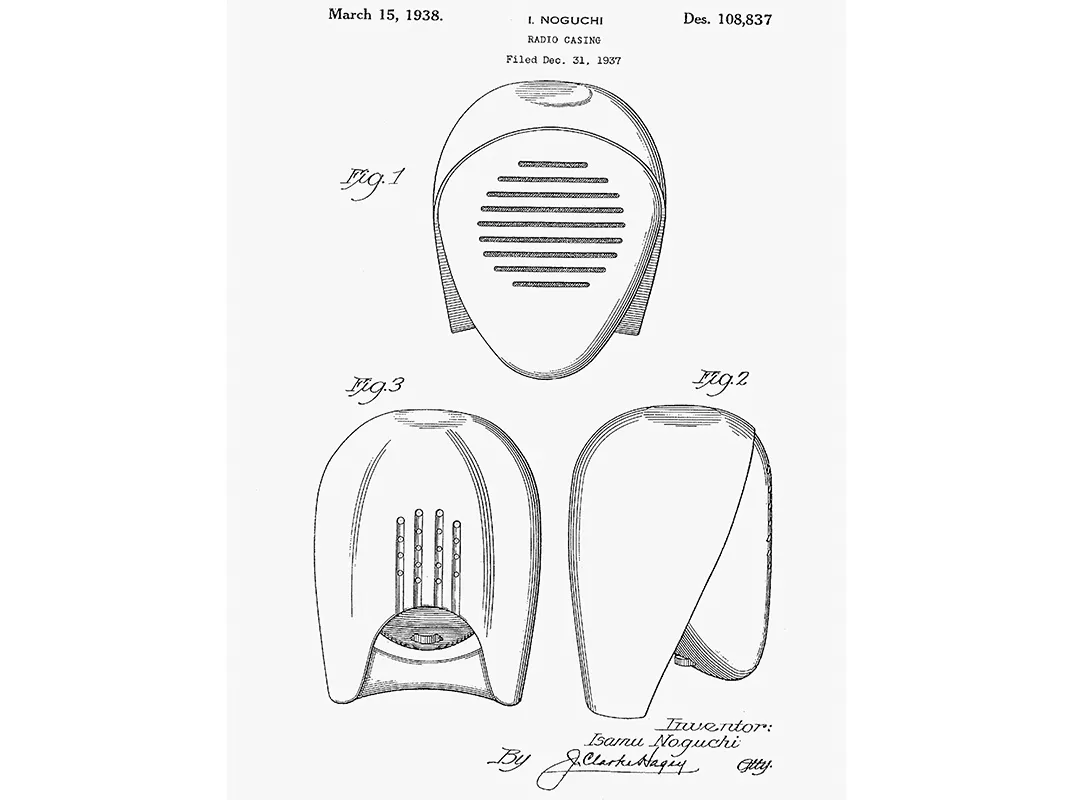

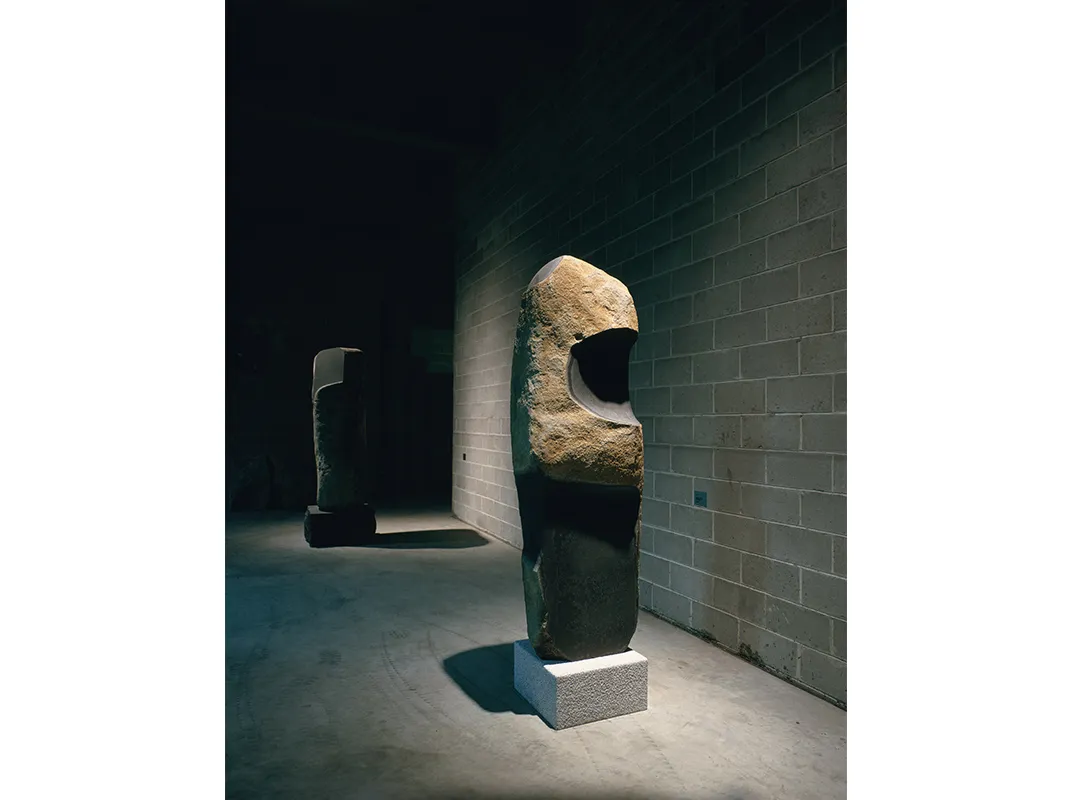

Eight inches high and made of black Bakelite, Isamu Noguchi’s Radio Nurse is not only a modern design that fits in with his monumental stone sculptures for which he is known, but the 1937 artwork is also the first working baby monitor.

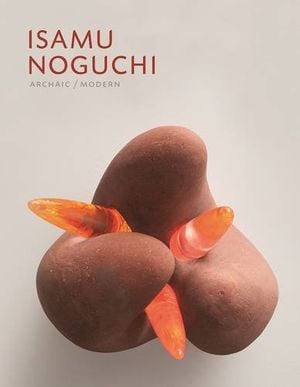

As one of the objects in the Smithsonian’s current retrospective “Isamu Noguchi: Archaic/Modern,” it has found a fitting home. The Smithsonian American Art Museum hosting the show was originally the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Noguchi submitted a patent application for the Radio Nurse covering the appearance of the receiver and was granted a design patent (D108,837).

It’s one of several patents he was granted that augment the exhibition of 74 works from the artist’s six-decade-long career, largely drawn from New York’s Noguchi Museum, that show his innovations in design—some of which endure today.

Despite its futuristic Art Deco design and fulfillment of what would prove to be a desirable parenting aid, Radio Nurse, a commission from the Zenith Radio Corporation in response to the Lindbergh baby kidnapping earlier that decade, did not succeed because its radio frequency overlapped with car radios and garage door openers.

But some other of Noguchi’s designs were much more successful. His 1950s Akari light sculptures that blended the simplicity of ancient Japanese Chinese lanterns with the modernism of electricity continue to be manufactured as high-end design, but also in an array of knockoffs.

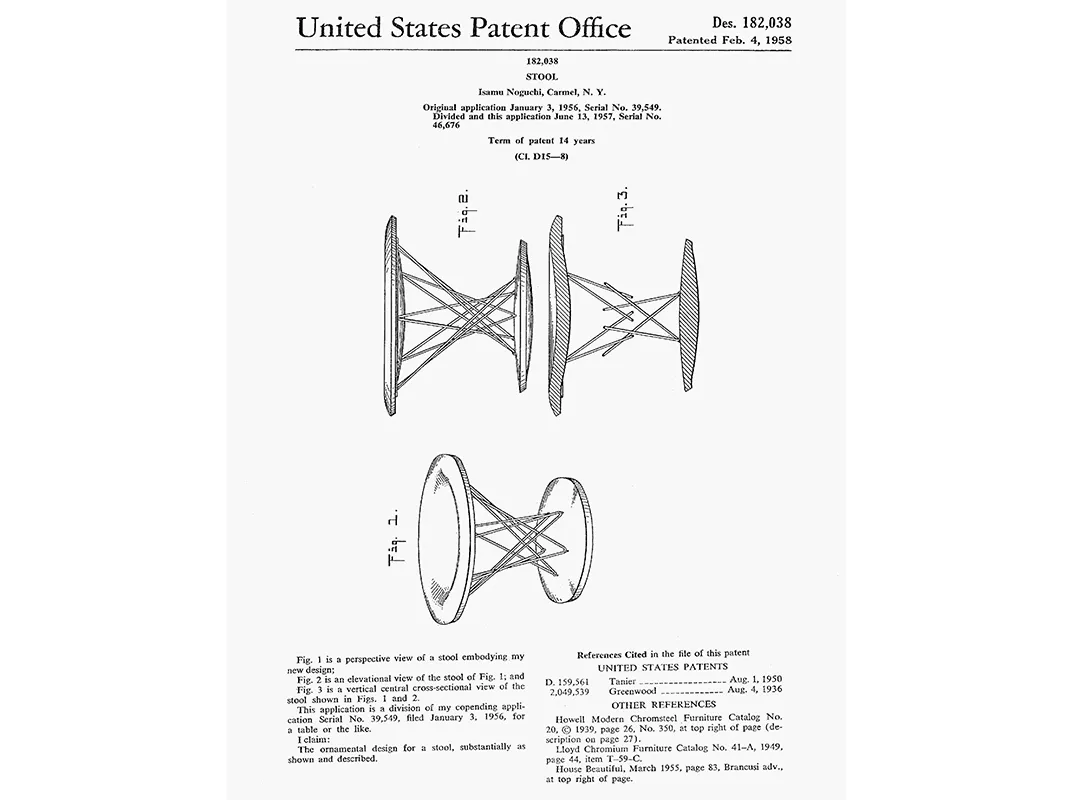

Also on display in “Archaic / Modern” are examples of the artist's wire form tables and stools, and a kidney shaped Freeform Sofa from about 1948, as well as a walnut and glass Coffee Table, first introduced in 1948—and all still being manufactured.

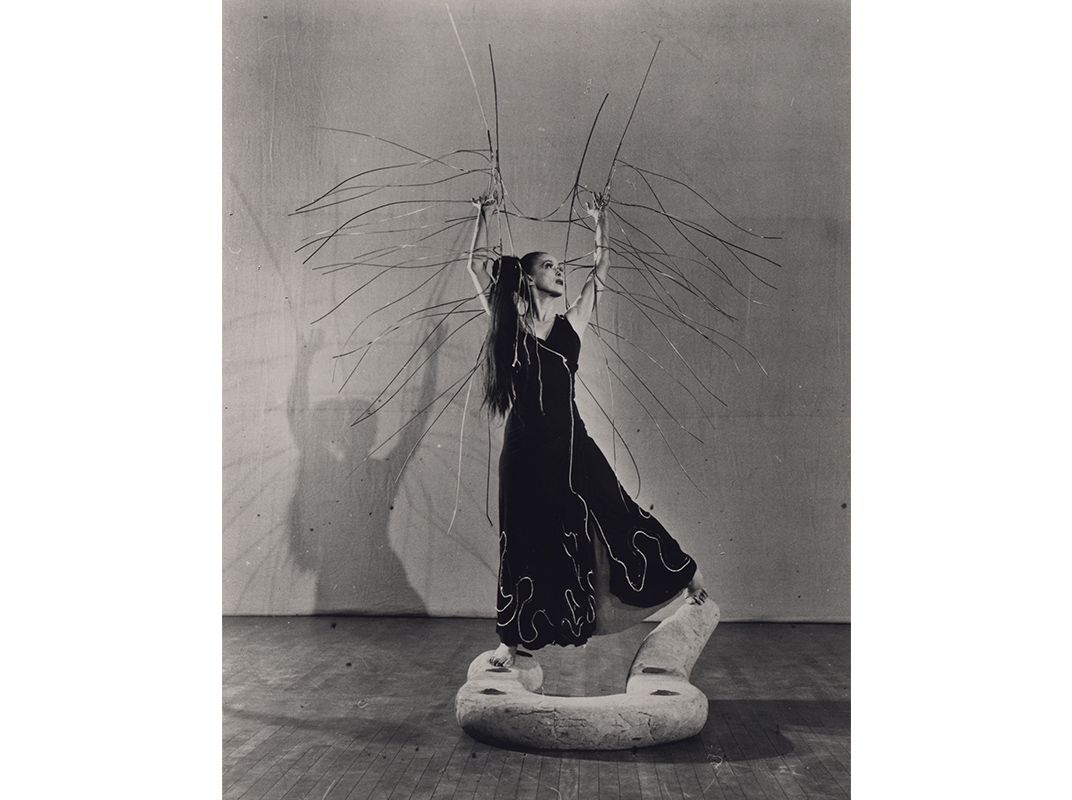

Just as the artist didn’t see a difference between the ancient and the modern futuristic forms, Noguchi spent his career blending art and design.

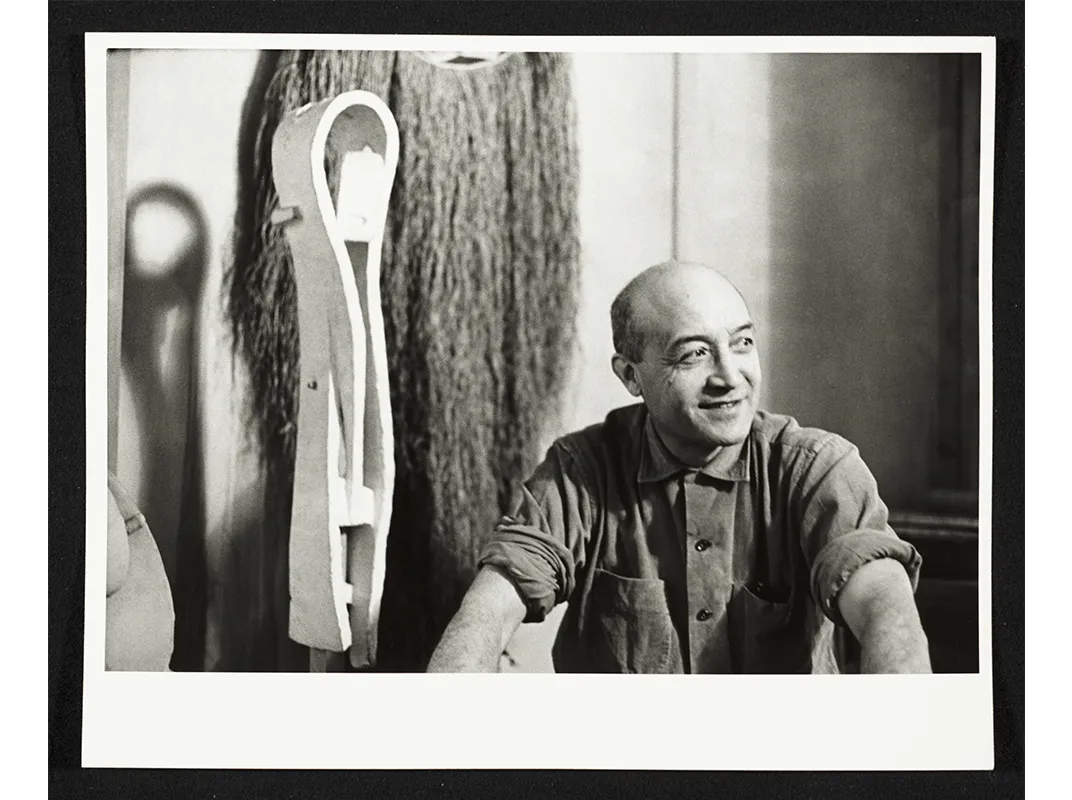

Born in Los Angeles in 1904, Noguchi was raised and educated in Japan, Indiana, New York and Paris—a background that made him “among the first American artists to think like a citizen of the world,” says Betsy Broun, the Margaret and Terry Stent Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

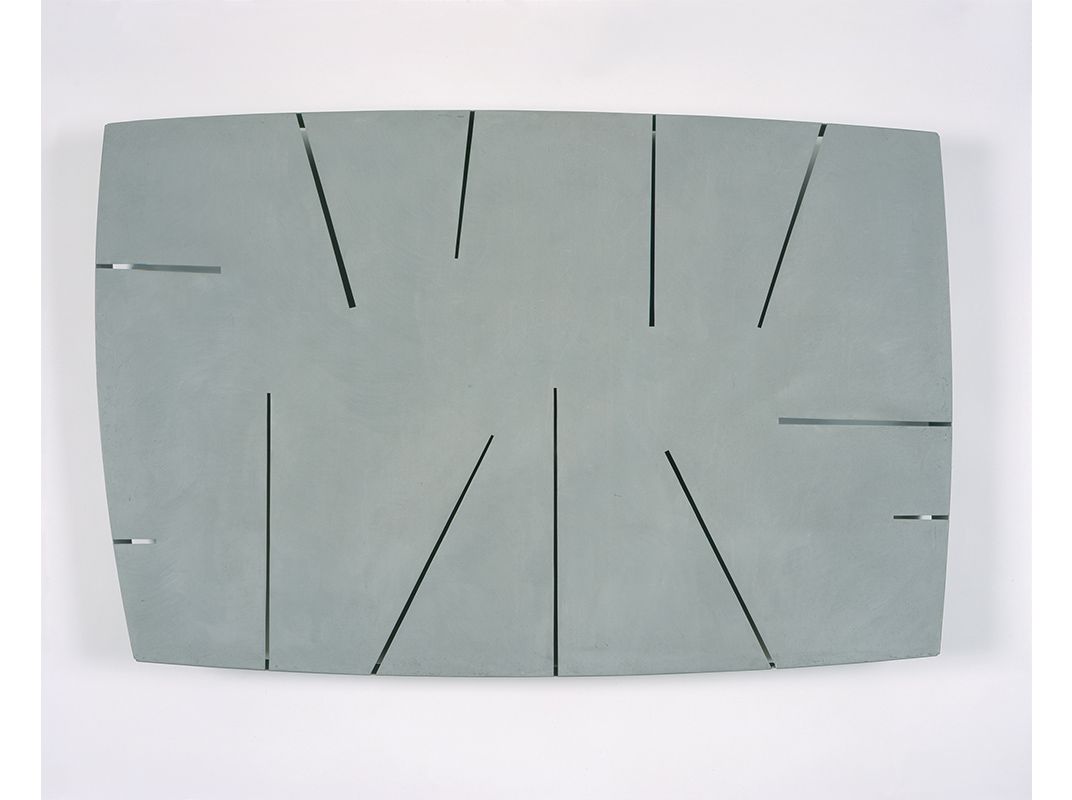

As well known as he became for fine art and for monumental stone works like the 1967 Grey Sun, Noguchi remained fascinated by inventors and industrialists like Alexander Graham Bell and Henry Ford, who he once called the true American artists.

Dakin Hart, the senior curator at the Noguchi Museum, says, “Thirty or 40 years ago, doing any kind of commercial work was seen to undermine serious work of the sculptor.”

“Even his dealer Arne Glimcher at Pace Gallery said he spent his entire career—50 years he worked with Noguchi—trying to protect Noguchi the sculptor from Noguchi the designer in order to maintain a market position,” says Hart, who organized the exhibition with Smithsonian American Art Museum curator of sculpture Karen Lemmey.

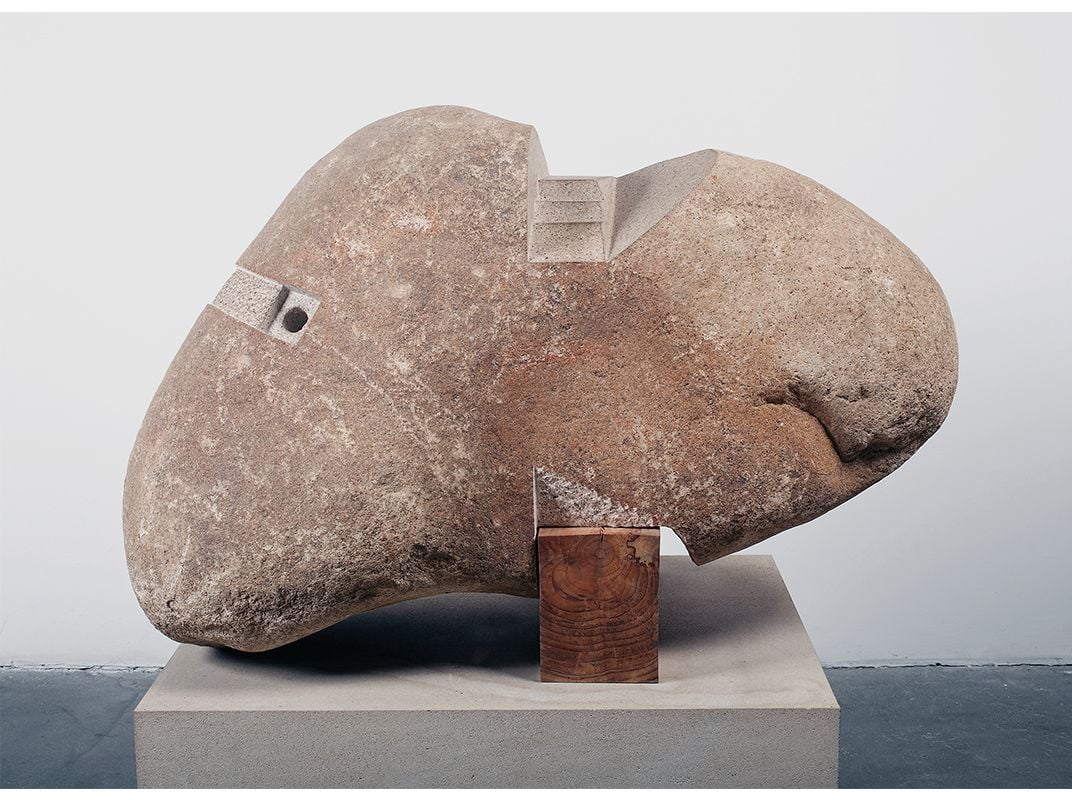

“But of course almost all of his great sculptural work came out of his work as an industrial designer,” Hart says. “So often genius in one area is just the imported conventional wisdom from another field. Noguchi was brilliant at doing that.”

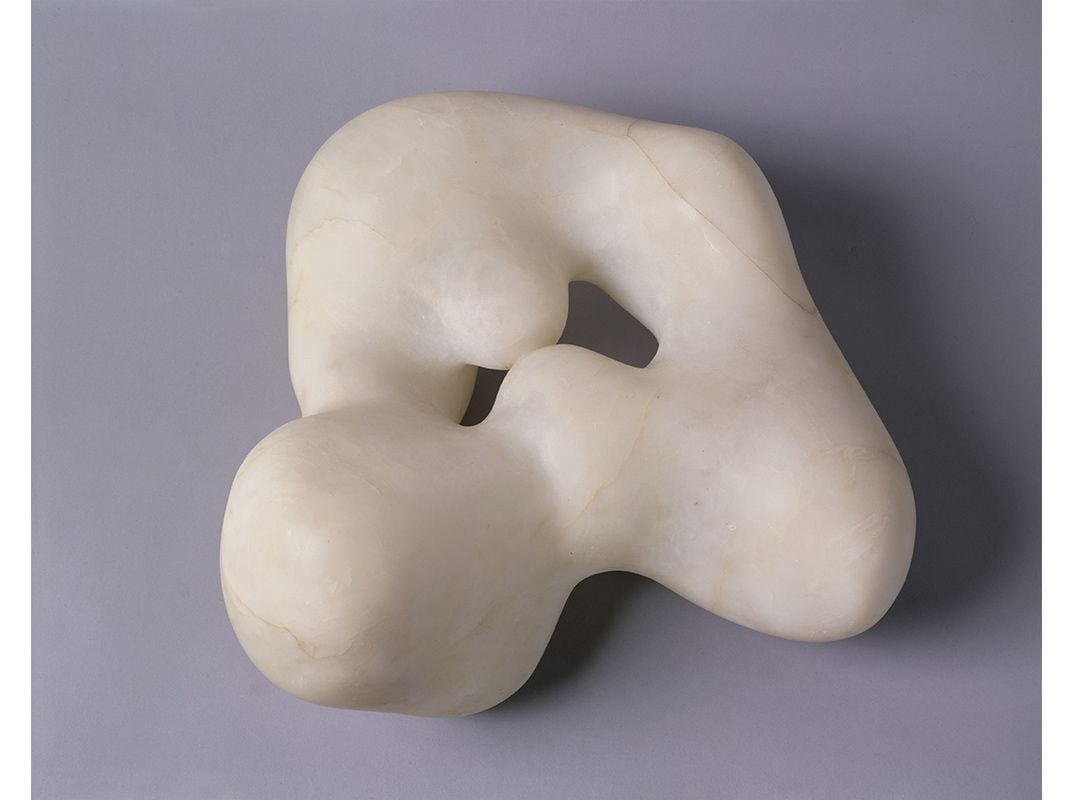

Indeed, many of his most successful sculptures blended the traditions of, say, a stone Japanese fountain, with modern technology that allowed water to run continuously through it as he does in The Well. Likewise, his Red Lunar Fist combined a bioluminescent chunk of crystal-bearing cave work with elements of an electric wall lamp. It is featured prominently on the cover of the accompanying catalog.

But his Akari light sculptures—with various patent applications on display—were his most popular and enduring creations. Using paper, bamboo and metal, Noguchi created a series of lamps that combined the inventions of the 20th century with Chinese paper lantern traditions that date to 230 B.C. The lamps continue to be updated, currently with LED lighting, which is something the artist would have appreciated, Hart says.

“The Akari form was all about proving a theory,” he says, “which was that washi paper, which was made from mulberry bark, could naturalize electric lighting. That was his hope. If you passed electric light through paper you could get something that felt like daylight again.”

“That was the excitement for him—naturalizing a newer technology into something that felt real, that felt connected, that felt of the natural world,” he says.

It was such a perfect combination, of course it was copied at the most popular household design stores.

“It’s infuriating what has happened to this idea,” says Lemmey. “Of course the best ideas are often imitated. There’s so much subtlety to these Akari lights—the mulberry paper, the bamboo, the tradition. You could substitute a metal dowel and lower the price, but there’s an authenticity to it. And he saw the sale of it supporting his studio museum.”

He opened his Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum in his studio and home in Long Island City, New York, a few years before his death in 1988 at 84.

Many of his designs of home furnishings, displayed among his sculptures in the Smithsonian show, are still popular, from the Noguchi Freeform Sofa to the Cyclone Tables.

Of the latter, the tables feature a base and top, which is not resting on the wire stem, but held together by tension, like a bicycle wheel. His patents from February 1958 explore how they work.

“They look so simple, but they’re really not simple,” Hart says of the table designs. “The structural rigidity of it comes from the fact that they’re strung together like a bicycle wheel.”

“Up to its limit, it works very very well,” he says. “But if I sat on this, all the wires would just collapse in a circle.”

There were also problems with his invention of a rocking stool of a similar design. “It really rocks, so there were some accidents,” Hart says. “People would use it as a step stool—not a good idea.”

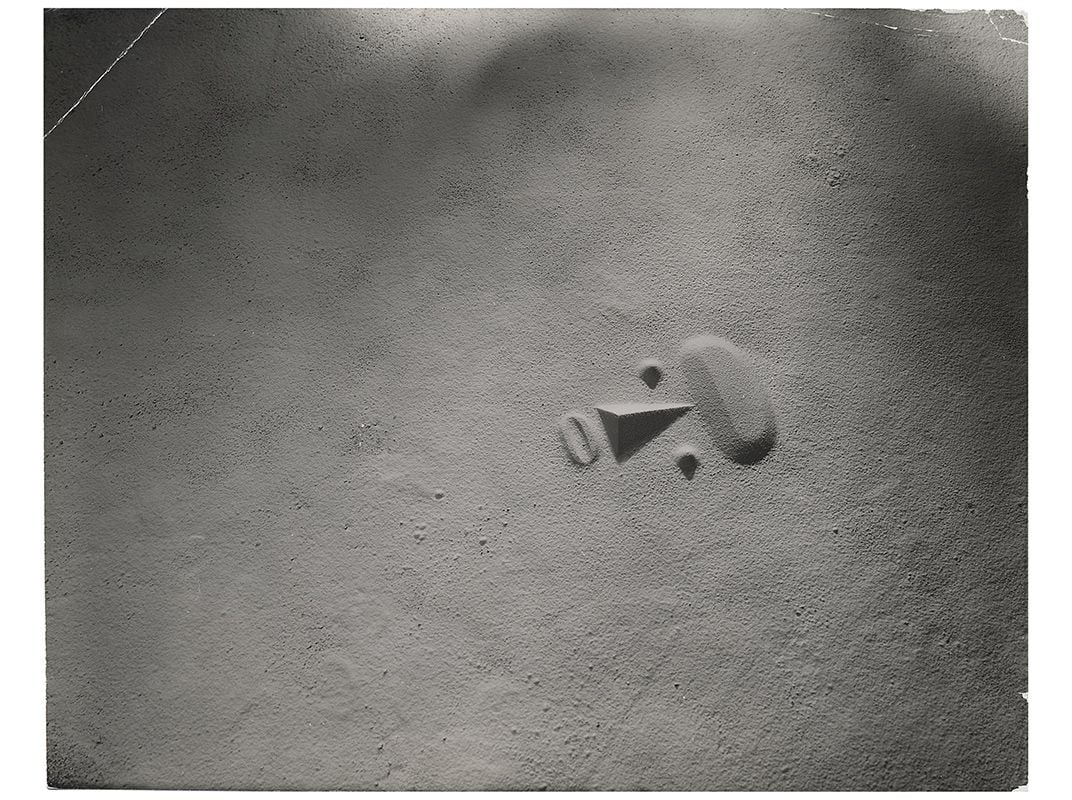

Like the Radio Nurse, not all of Noguchi’s design inventions came to pass. “He was obsessed with designing the perfect ashtray,” Hart says. But his patent application for one that featured fingers as if out of a Louise Bourgeois sculpture wasn’t accepted by the patent office.

The Radio Nurse, used in combination with a crib-side box called the Guardian Ear, was at first accepted enthusiastically by Zenith, which commissioned it.

“Zenith was the Apple of the '30s,” Hart says. “It made all of the cool new products that people wanted in their home.”

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh’s baby in 1932 followed by the arrest, trial and execution of Richard Hauptmann in the subsequent years, created interest in a device that would better keep track of children in the home. But not just any box of wires.

“What the president of Zenith realized was that he needed something people would be proud to have in their living room,” Hart says. “It had to be good design. And it was widely received that way. It was exhibited and won design awards.”

But despite a few years of manufacture, it failed.

“The radio frequency technology that it used interfered with regular radios and the new technology of the time, which were for electric garage doors,” Hart says. “Signals were being crossed. It actually meant that driving by in a car you could pick up the transmissions of the Radio Nurse on your car radio.

“Which was the exact opposite of what it was trying to do, because it was sold as a security device,” he says. “But anybody driving by would know there’s a baby in that house.”

Still, he adds, “as a formal thing it’s neat because he did what he usually does, which is be able to synthesize three really interesting things: the traditional kendo mask, the bamboo sword fighting practice mask, with a period nurse’s cap, which still looked a little bit like a wimple, and of course, it’s a robot head. It’s an automaton. So it’s synthesizing together three really different figures of authority into something that feels purposeful and a little bit severe, but hopefully not terrifying.”

It wasn’t until another generation that the kind of baby monitors used today came onto the market.

And when a vintage Noguchi Radio Nurse came up for auction in 2008, the price was a surprising $22,800.

"Isamu Noguchi, Archaic/Modern” continues at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. through March 19, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/4a/ab4ae891-16f8-4884-b930-366d9d9e843b/age-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)