Is Architecture Actually a Form of Weaving?

David Adjaye, architect of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, approaches building design as creating “fabric”

David Adjaye is known for his innovative architectural designs. He integrates a wide array of influences into his own kind of modernism in projects as diverse as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver, the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture—perhaps his most ambitious project to date—expected to be opened next year in Washington, D.C. So it may seem strange that a man celebrated for his buildings would also be curating an exhibition about fabric.

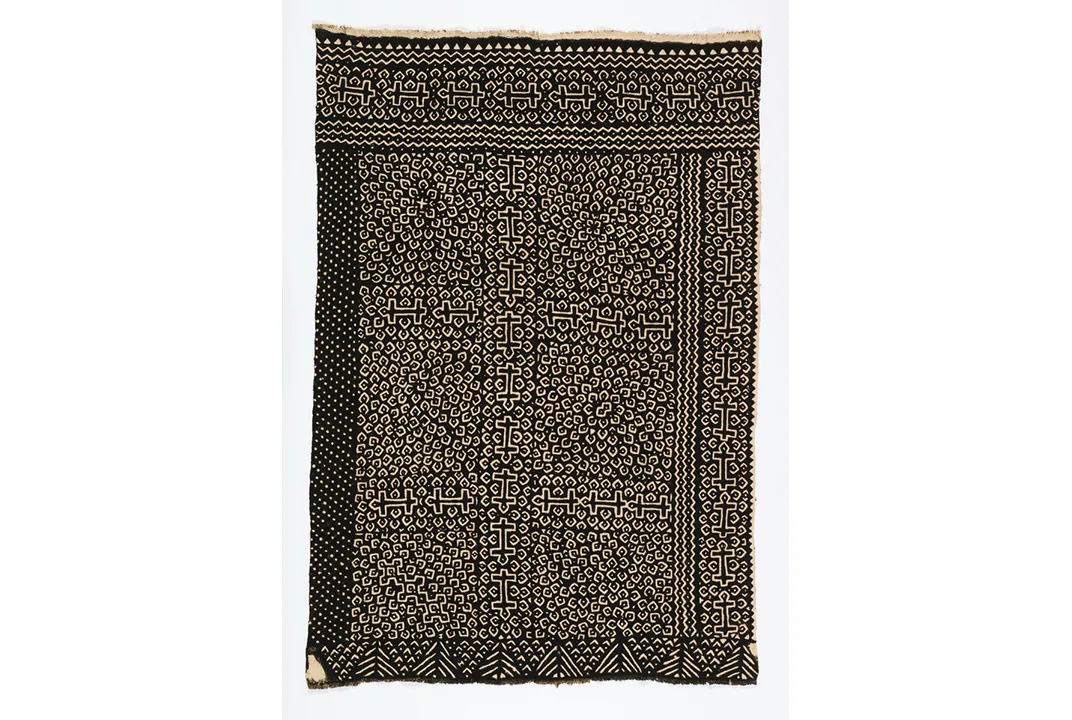

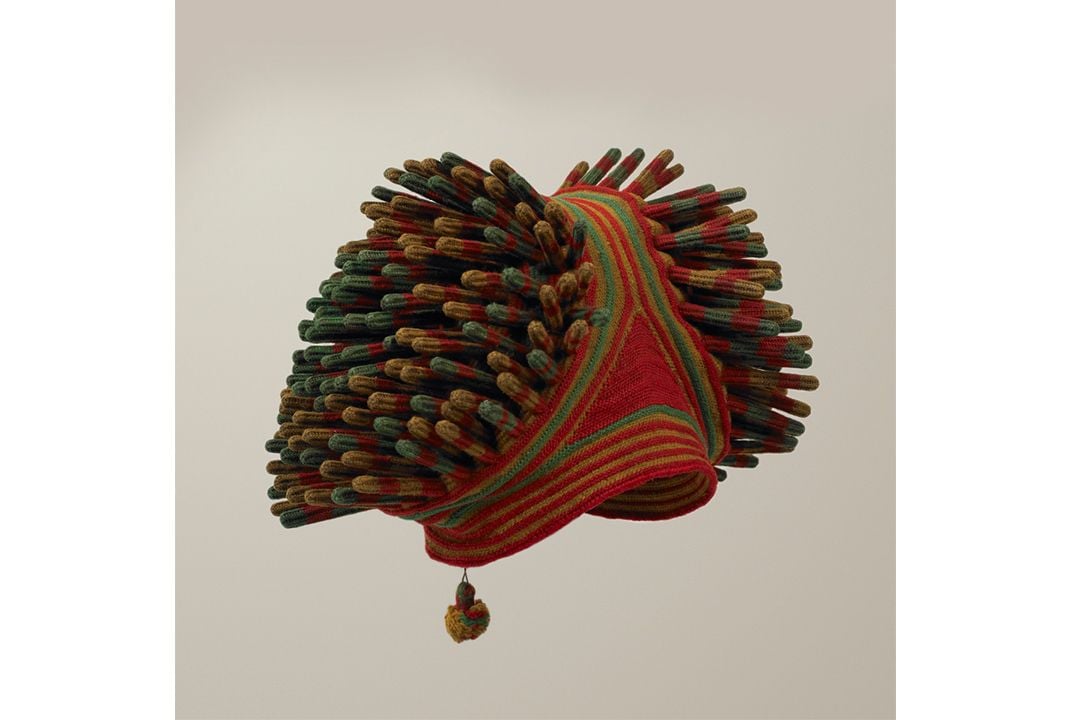

Adjaye is overseeing the newest installment of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s “Selects” series, which spotlights the little-known West African textiles in the museum’s permanent collection. The show spotlights 14 colorful cloths, caps and wraps from communities throughout Africa. It also offers the celebrated architect a chance to explore the surprising connections between textile making and building design.

“What’s interesting to me is this idea of fabric and weaving as a kind of abstraction of making places that people come together in,” he says.

Adjaye says that the overlap of these two disciplines has always fascinated him. He sees it as a way to understand architecture that was first explored by thinkers like 19th-century German architect Gottfried Semper in his influential work The Four Elements of Architecture. The book made the case that building one of the elements, enclosure, actually originated as textiles—first as interwoven grasses and branches, which gave way to woven screens and tapestries, before more solid walls served as dividers of space.

This concept of textiles as dividers of space is partly why Adjaye has displayed the fabrics upright in the exhibition instead of flat—to transform them from fabric into “architectural elements.”

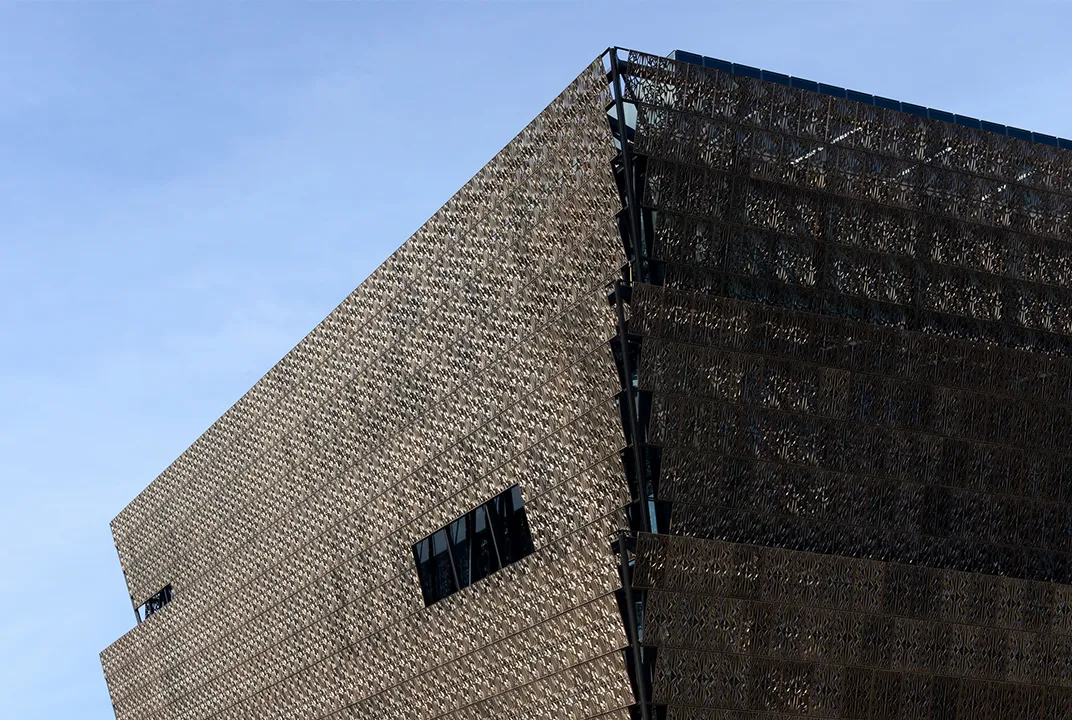

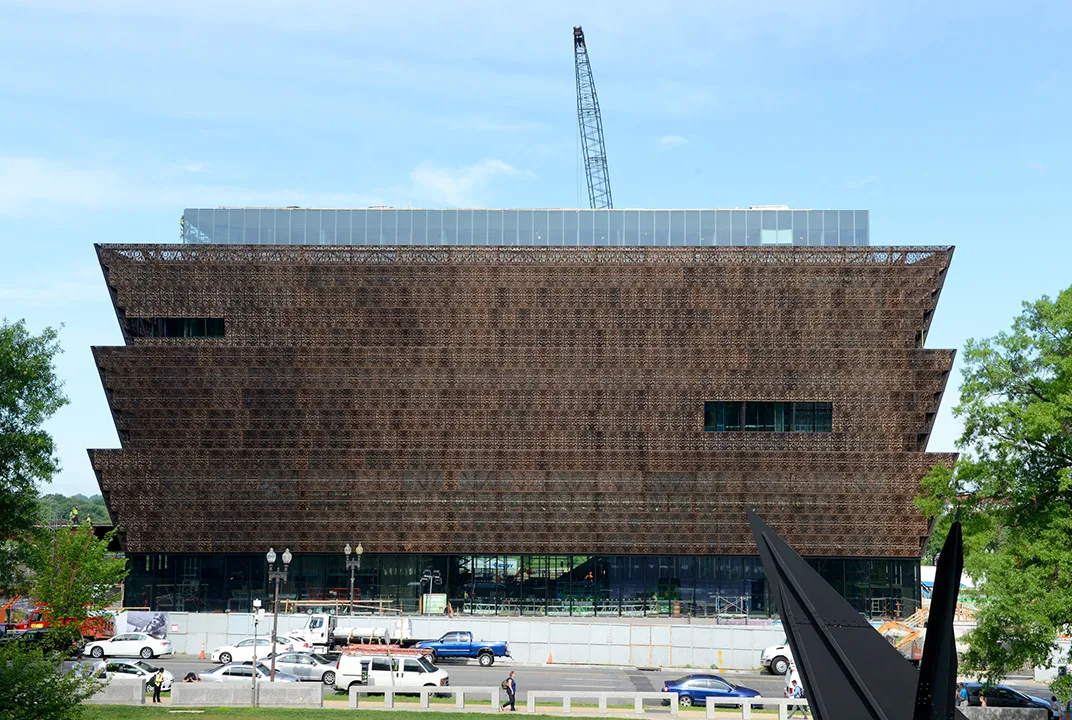

This blend of architecture and textiles can be seen in his design of the edifice of the African American History Museum as well (for which Adjaye is serving as lead designer, along with the project’s lead architect, Philip Freelon). In particular, the outside of the building is bronze mesh that references the professional guilds of the freed African-American communities of the South, particularly South Carolina and Louisiana. It required an algorithm that mimicked an actual Charleston house and demanded that Adjaye and his team create a new bronze-coated alloy.

“Textiles, especially West African textiles, often demonstrate a paradoxical juxtaposition of regularity and serendipity,” says Kim Tanzer, a professor of architecture at the University of Virginia. “I see this quality in the walls of the [museum].”

She points to the “visual and structural meter” set by the floor levels and upward-slanting walls of the museum; the individual bronzed panels, which create “a secondary rhythm;” and the “syncopation” provided by the gaps between those walls. All of this creates a façade that shares elements with something that would fit comfortably into the Cooper Hewitt’s “Selects” exhibition.

The son of a Ghanaian diplomat, Adjaye spent his childhood moving through very different countries and cultures—Tanzania, Egypt, Lebanon and England—and has since visited every one of Africa’s 54 nations. He describes the incorporation of these varied backgrounds into his art as a type of weaving, synthesizing distinctive elements in a way that creates a new sort of singular whole.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/51/f85166dd-6ff7-4674-86ea-d93da88f9c02/davidadjaye-02-web-resize-1072x720.jpg)

For the exhibition, Adjaye was given full access to the Cooper Hewitt’s archives and its collection of 26,000 textiles found himself quickly drawn to its colorful African fabrics. The individual pieces reflect what he calls a “common memory” of each particular place and its culture—symbols from proverbs of the Asante people on a funeral wrap; or projections sprouting from a Cameroonian hat meant to symbolize the wearer’s inner thoughts. At the same time, Adjaye saw all these pieces as forming together their own kind of “mosaic of the geography and cultural lines” of the continent and its myriad people.

Adjaye sought to avoid presenting the pieces as “so-called ethnic objects,” to approach them instead as lenses through which he could take a more abstract look at materials, technique and geography. The exhibition attempts to read the collection from this perspective—telling how the textiles’ colors reflect the mineral quality of a jungle versus a mountain, or how their patterns reflect the dynamic of one city versus another. Each wrap and cap becomes a symbol of its community, and together the pieces more broadly weave a larger textile of West Africa.

“That is absolutely analogous to my thinking of architecture right now,” says Adjaye. He sees both textile and architecture as a “cultural frame that allows society to flourish.”

Adjaye emphasizes that the influence of these textile patterns can be seen throughout his architectural works. He points to the geometric shapes of the façade of London visual arts center Rivington Place and the colorful diamonds of Washington, D.C.’s Francis A. Gregory Library. His latest museum may be the clearest example of this overlap yet.

Just as the Selects exhibit required Adjaye to encapsulate a diverse and complicated history into a unified whole, that has been his challenge with the African American History Museum.

He sees the project as a new type of museum that he believes “we’re going to see more of in the 21st century” —focusing on the story of a particular group, rather than collected objects, to understand a place more broadly. It’s about “understanding the complex, fantastic and difficult history of America through the lens of the African-American people,” as Adjaye puts it. He points to the National Jewish Museum and the National Museum of the American Indian as moving in that direction and expects this to be a growing trend for museums both in the U.S. and throughout the world.

Set at the corner of 15th Street N.W. and Constitution Avenue, the 380,000-square-foot museum is designed to convey this weaving of culture and history. It includes a 116-foot-tall building topped by a three-tiered copper “Corona,” housing the museum’s gallery spaces. Its main entrance is a striking “Porch.” In the façade, Adjaye incorporates elements of artwork from the Yoruba people of West Africa, what he calls “a powerful artistic tradition across central and west Africa” that forms “part of a deep, psychic territory of this community.”

“In part, Adjaye’s personal design narrative embodies the 400-year-long trajectory of Africa in diaspora—rich African sources and European intellectual frameworks, informed by the research he and his team did to understand and incorporate craft traditions of the 19th-century American, especially antebellum, South,” says Tanzer. “The [museum] is a beautiful example of the strategic ‘borrowing’ that created the rich cultural environment we have all inherited from the African continent.”

"We wanted a building that is worthy of a rich cultural heritage, and we wanted it to work as a museum," says Lonnie G. Bunch, the museum's founding director and chairman of the jury that selected Adjaye's design. In addition to the specific physical dimensions and environmental considerations, Bunch had instructed the architects to reflect in their designs the optimism, spirituality and joy, as well as the "dark corners" of the African American experience.

Adjaye emphasizes that the African American History Museum is “not a museum for African-Americans, it’s a lens through which to understand the mosaic of America and what makes America.” And like a textile that fits a particular culture and location, he sees his architectural projects as growing out of a particular geography and place, rather than the other way around.

“My buildings look different in each context—if I worked in the same place twice, it would probably be the same kind of building,” he says. “If I work in a new place, new forces come into play.”

"David Adjaye Selects" is on view through February 14, 2016 in the Marks Gallery at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum at 2 East 91st Street in New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)