Bearing Witness to the Aftermath of the Birmingham Church Bombing

On September 15, 1963, four were killed in the Ku Klux Klan bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130913035038birmingham-church-modern-day-470.jpg)

On September 15, 1963, two and a half weeks after the March on Washington, four little girls were killed in the Ku Klux Klan bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Addie Mae Collins, 14, Denise McNair, 11, Carole Robertson, 14, and Cynthia Wesley, 14, were the youngest casualties in a year that had already seen the murder of Medgar Evers and police brutality in Birmingham and Danville.

For many Americans, it was this single act of terrorism, targeted at children, that made plain the need for action on civil rights.

Joan Mulholland was among the mourners at a funeral service for three of the girls on September 18, 1963. (A separate service was held for the fourth victim.) Thousands gathered around nearby 6th Avenue Baptist Church to hear Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who observed that “life is hard, at times as hard as crucible steel.”

Mulholland, a former Freedom Rider who turns 72 this weekend, was then one of the few white students at historically black Tougaloo College in Mississippi. She and a VW busload of her classmates came to Birmingham to bear witness, to “try to understand.” She says of the victims, “They were so innocent—why them?”

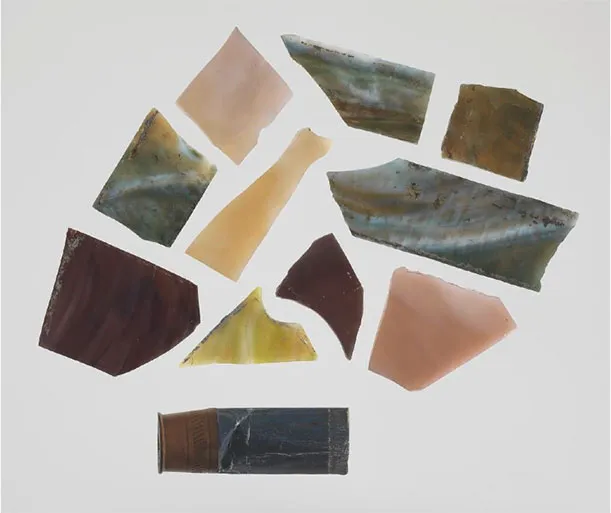

Mulholland stopped at the ruined 16th Street church first, picking up shards of stained glass and spent shotgun shell casings that remained on the grounds three days after the bombing. Ten of those shards of glass will join one other shard, recently donated by the family of Rev. Norman Jimerson, in the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. For now, Mulholland’s shards can be viewed in “Changing America: The Emancipation Proclamation, 1863 and the March on Washington, 1963” at the American History Museum.

Mulholland joined us for an exclusive interview in the gallery. She is a short, sturdy woman with a quiet demeanor, her long white hair tied back in a bandana. A smile flickers perpetually across her lips, even as her still, steel blue eyes suggest that she has seen it all before.

As a SNCC activist in the early 1960s, Mulholland participated in sit-ins in Durham, North Carolina, and Arlington, Virginia, her home. She joined the Freedom Rides in 1961 and served a two-month sentence at Parchman State Prison Farm.

Looking back, Mulholland recognizes that she was a part of history in the making. But at the time, she and other civil rights activists were just “in the moment,” she says, “doing what we needed to do to make America true to itself—for me particularly, to make my home in the South true to its best self.”

Mulholland spent the summer of 1963 volunteering in the March on Washington’s D.C. office. On the morning of the March, she watched as the buses rolled in and the crowds formed without incident. That day, she says, was “like heaven”—utterly peaceful, despite fear-mongering predictions to the contrary.

Eighteen days later, the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church changed all that. “Things had been so beautiful,” Mulholland remembers, “and now it was worse than normal.” The explosion, which claimed the lives of four children and injured 22 others, set off a wave of violence in Birmingham. There were riots, fires and rock-throwing. Two black boys were shot to death, and Gov. George Wallace readied the Alabama National Guard.

The funeral on September 18 brought a respite from the chaos. Mourners clustered in the streets singing freedom songs and listened to the service from loudspeakers outside the 6th Avenue church. “We were there just in tears and trying to keep strong,” Mulholland recalls.

The tragedy sent shockwaves through the nation, galvanizing the public in the final push toward passage of the Civil Rights Act. “The bombing brought the civil rights movement home to a lot more people,” says Mulholland. “It made people much more aware of how bad things were, how bad we could be.” As Rev. King said in his eulogy, the four little girls “did not die in vain.”

Mulholland hopes that her collection of shards will keep their memory alive. “I just wish this display had their pictures and names up there,” she says. “That’s the one shortcoming.”

After graduating from Tougaloo College in 1964, Mulholland went back home to the Washington, D.C. area—but she never really left the civil rights movement. She took a job in the Smithsonian’s Community Relations Service and helped create the first Smithsonian collection to document the African American experience. She donated many artifacts from her time in the movement—newspaper clippings, buttons and posters, a burned cross and a deck of cards made out of envelopes during her prison stint, in addition to the shards from Birmingham.

She kept some of the shards and sometimes wears one around her neck as a memento. “Necklace is too nice a word,” she says.

Others she used as a teaching tool. From 1980 to 2007, Mulholland worked as a teaching assistant in Arlington and created lessons that reflected her experience in the civil rights movement. She brought the shards to her second grade class, juxtaposing the church bombing in Birmingham with the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa.

“I saw second graders rubbing this glass and in tears as it was passing around,” she says. “You might say they were too young. . . but they were old enough to understand it at some level. And their understanding would only grow with age.”

Fifty years after the bombing, Mulholland says that “we aren’t the country we were.” She sees the ripple effects of the sit-ins culminating, but by no means ending, with the election of President Barack Obama in 2008. And while the struggle for civil rights isn’t over, she says, when it comes to voting rights, immigration reform, gender discrimination and criminal justice, Mulholland remains optimistic about America’s ability to change for the better.

It’s “not as fast as I’d want,” she says. “I think I’m still one of those impatient students on that. But the changes I’ve seen give me hope that it’ll happen.”