The Discovery of a Tiny Tyrannosaur Adds New Insight Into the Origins of T. Rex

The horse-sized dino species had smarts and a keen sense of smell, setting the stage for the evolution of the enormous predator

:focal(781x403:782x404)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/0d/c30da39b-4d47-4dba-8207-9027650264e9/sues3web.jpg)

There’s no dinosaur quite like Tyrannosaurus rex. The giant, flesh-eating “tyrant king” has dominated our imaginations for more than a century, snarling at us from museum halls and Hollywood blockbusters. But how did one of the biggest carnivores to ever walk the Earth get to live so large?

A new fossil find from Uzbekistan adds a crucial clue, underscoring the fact that this celebrated family of sharp-toothed dinosaurs didn’t always rule.

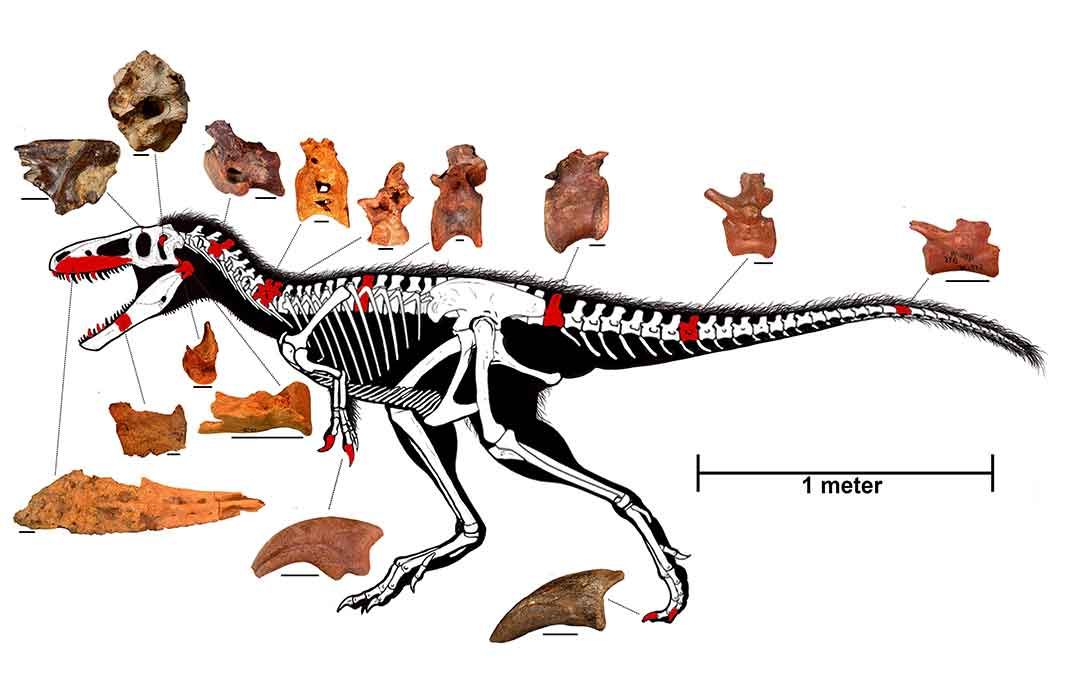

The new dinosaur, named Timurlengia euotica by National Museum of Natural History paleontologist Hans-Dieter Sues and colleagues today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), took a circuitous route to discovery. Back in 2012 Sues and study coauthor Alexander Averianov described a smattering of bones from the 90-million-year-old rock of Uzbekistan’s Kyzylkum Desert. The pieces were definitely those of a small tyrannosaur, Sues says, but the bones “did not have the unique features or a unique combination of features that would have allowed us to distinguish our animal from other tyrannosaurs.”

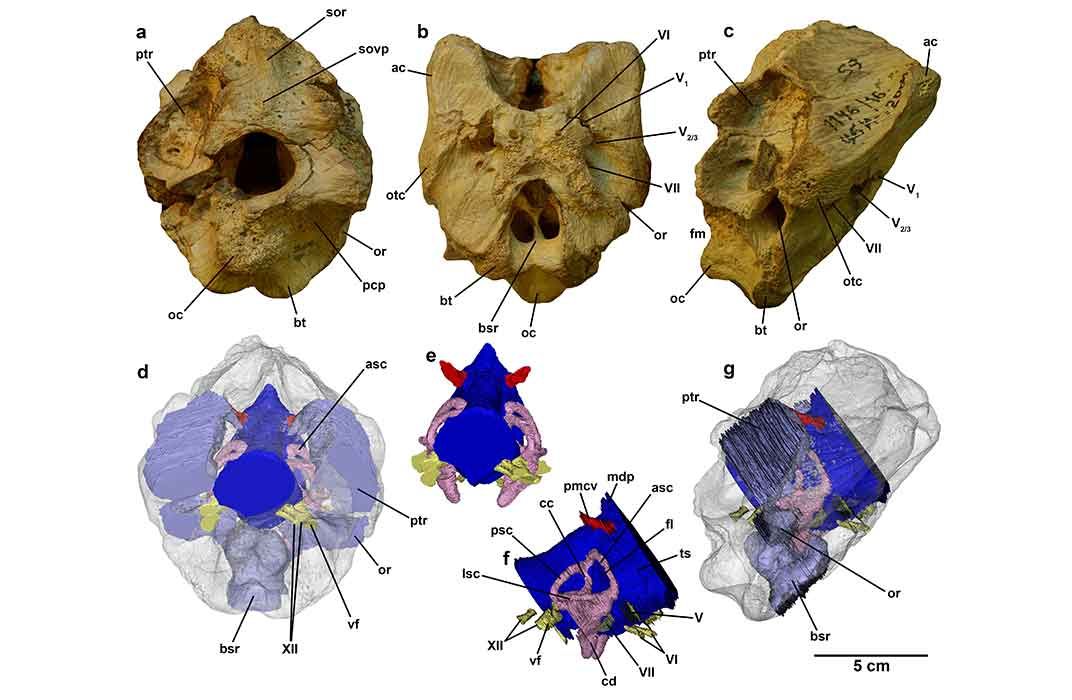

A braincase changed all that. The ancient skull piece, found in the same rock layer, showed that the Uzbekistan tyrannosaur was definitely something different from its relatives found elsewhere. Combined with the previously discovered pieces, which Sues and colleagues attribute to the same species, Timurlengia emerges as a pint-sized version of the charismatic dinosaurs that would come to terrorize the Cretaceous 20 million years later.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/f5/14f530f9-078c-4d77-8c8c-bf8b134b5157/sues1web.jpg)

“Timurlegnia would have been a small, slender-limbed version of the ‘tyrant king’,” Sues says, albeit with a stature comparable to a modern horse. And while the fossils show that Timurlengia had some important differences from later, larger tyrannosaurs, such as teeth that were slimmer and better suited to slicing flesh than puncturing bone, Sues notes that details of the braincase and inner ear indicate that the small carnivore “had a keen sense of hearing and excellent eyesight” that would characterize the giant tyrannosaurs that came later.

Such a tiny terror is exactly what paleontologists have been expecting, says North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences paleontologist Lindsay Zanno. While noting that “the specimen itself is a great discovery,” Zanno points out that her team, the authors of the new study and others have established that tyrannosaurs stood in the shadow of larger carnivores for the early part of the Cretaceous, with Timurlengia continuing the trend. This is part of the broader goal of paleontology, Zanno says, establishing who lived where and when to then draw out larger evolutionary patterns.

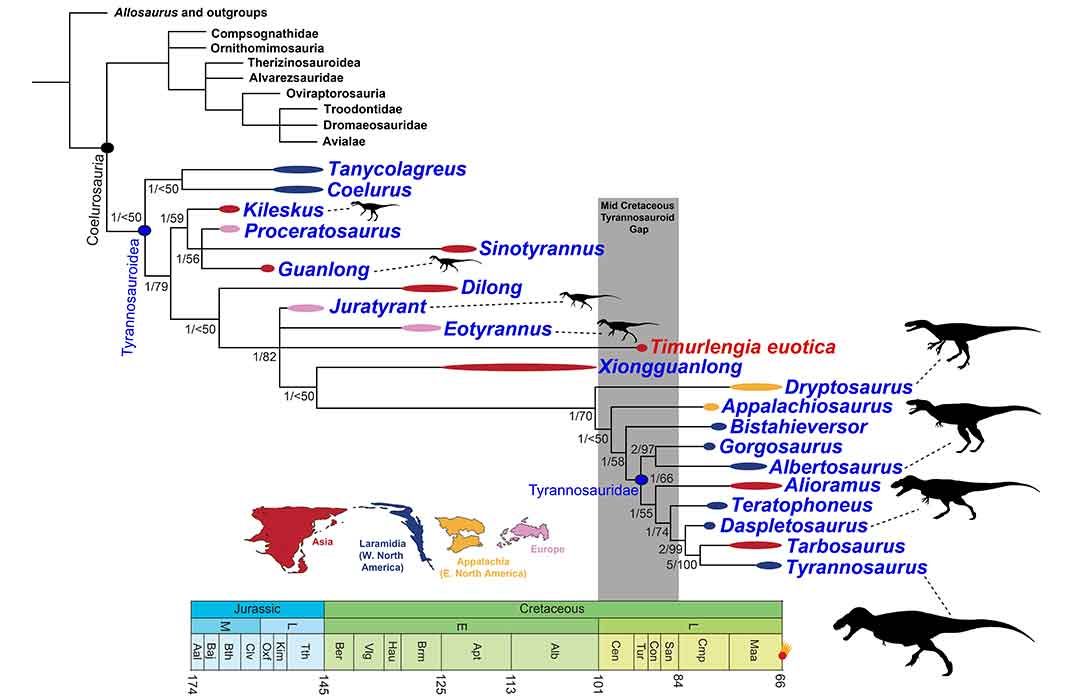

For its own part, the dinosaur’s place in time makes Timurlengia so striking. Paleontologists know that the very first members of the tyrannosaur lineage split from their relatives in the Jurassic, about 170 million years ago. They were small, slender and had three claws on long arms.

The first truly giant tyrannosaurs—the species that set up the rise of T. rex—didn’t evolve until about 80 million years ago. At about 90 million years old, the much smaller Timurlegnia represents a little-known time in tyrannosaur evolution and throws additional evidence to the idea that, despite their imposing title, tyrannosaurs stayed tiny for tens of millions of years before growing to snatch the title of apex predator.

So while the name “tyrannosaur” might remind us of 40-foot-long, 9-ton giants, for most of their history these dinosaurs lived on the margins of habitats dominated by relatives of Allosaurus and other types of carnivore. And this time period molded tyrannosaurs into what they’d eventually become. “The small early tyrannosaurs were competing with various other theropods,” Sues says, “and presumably their neurosensory capabilities evolved in that ecological context.”

Their sharp sense of smell and excellent eyesight didn’t let tyrannosaurs muscle out the competition, in other words. Instead these traits let them take over when extinction swept their rivals from the evolutionary stage. “When other megapredators bowed out, tyrannosaurs were primed to pick up the slack,” Zanno adds. Tyrannosaurs had to get lucky before they could become the monstrous predators we adore.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/39/c939a906-2244-4bdc-9ceb-4268fed3b27a/sues2web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)