In the Early 19th Century, Firefighters Fought Fires … and Each Other

Fighting fires in early America was about community, property and rivalry

In a scene from the film Gangs of New York, set in Civil War-era Manhattan, a crowd gathers in the night as a fire breaks out. A volunteer fire department arrives, and then another. Instead of cooperating to extinguish the blaze, the rival fire companies head straight for each other in an all-out brawl as the building burns. According to the curator of a new display case exhibit on American firefighting in the 19th century, there is a certain element of truth behind the scene.

“It is certainly true that fire companies had rivalries that would turn physical,” says Timothy Winkle, deputy chair and curator of the division of home and community life at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. “There were rivalries in cities like New York and Baltimore where fire companies would go at it and be on opposite sides of civil unrest... Lets just say that somewhere in that scene is something in the spirit of what was beginning to be wrong with the state of volunteer firefighting at that point.”

As American towns grew into dense cities where a single fire could threaten the lives of thousands, the country lacked the types of institutions that fought fires. In England, firefighters were organized and paid for by insurance companies which only responded to fires at addresses that were insured. But there were no major insurance companies operating in early America. The first homeowners insurance company wasn't started until 1752 (by Benjamin Franklin) and didn't become common until the 1800's. By that time, Americans had developed their own tradition of fighting fires as a grassroots collective. The first response of those communities was what would later be called a “bucket brigade.” Neighbors from all around the fire would run to help or at least toss their buckets into the street for volunteers to fill with water and pass forward to be dumped on the fire.

Leather fire buckets, like the one displayed in the exhibit, were a ubiquitous part of urban life in 1800.

“In many communities they would be required,” says Winkle. “You would keep them in your front hall and throw them out into the street for people to use in the event of a fire. They were painted with names and addresses. When the fire is over, they all get taken to a church or other central place and people would pick them up.”

Newspapers of the era advertised the services of artists who would personalize and decorate fire buckets for a fee. The buckets became a way of participating in the protection of a community while also showing off social status. Throwing water on a fire one bucket at a time wasn't a very effective way of saving one particular house, but it could buy the occupants enough time to salvage some belongings and prevent the fire from spreading to other buildings and potentially destroying an entire neighborhood.

As firefighting equipment evolved from buckets to engines, the need for special training and tools emerged. Enter the creation of volunteer fire companies.

“Leonardo DiCaprio as the narrator [of Gangs of New York] calls them 'amateur' firefighters,” says Winkle “To say they are 'volunteers' is more accurate. Because even today, the majority of firefighters are still volunteers, but nobody would call them 'amateurs.' That can also be applied to the volunteers of the 1840s into the 1860's. They were as trained as the technology of the time allowed.”

American firefighting began to evolve into a system of fraternal organizations, similar to the Masons or the Oddfellows. “The volunteer firefighters of the early period are sort of the most virtuous members of the early republic,” says Winkle. “They're establishing themselves as manly heroes. . . with mottoes in Latin, hearkening back to the republics of old.”

One of their early tools was a bed key, designed to quickly disassemble a bed in order to remove it from a burning building. Before the introductions of gas lines, before houses were full of artificial accelerants, before buildings tended to be more than two stories tall, it was relatively safe to try to salvage property from a burning building.

“There's a big difference in priorities at that time,” says Winkle. “ If your house catches fire, it's probably going to be a loss. But it's likely that the fire will burn slowly enough that at least some things can be salvaged so at least you aren't losing your movable wealth. The bed was most likely your most valuable single item.”

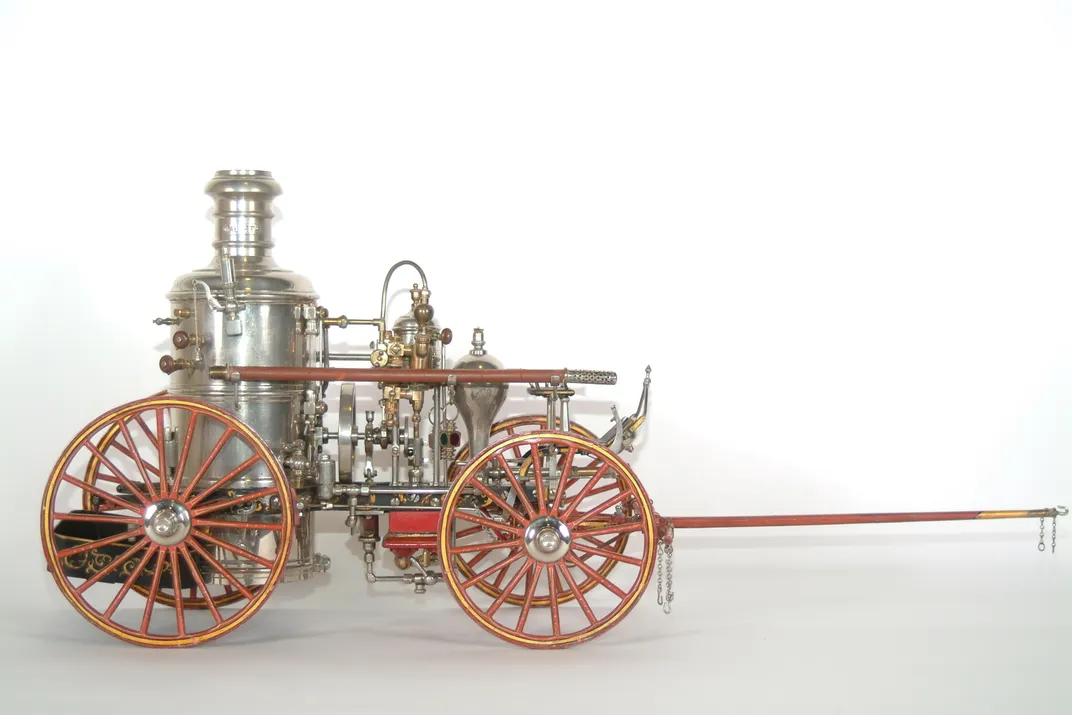

In the period around 1800, some early fire engines with manually operated pumps were horse-drawn, but large groups of strong men moved them around, just as depicted in the film. Hose companies were formed when municipal water sources were built with primitive hydrants. A riveted leather hose, like the sample on display in the exhibit, was invented to take advantage of pressurized water sources.

As buildings grew taller, stronger steam-powered pumps were needed. Those required fewer, but better-trained firefighters to operate. Shrinking the sizes of fire companies was somewhat of a social problem. Volunteer fire companies existed to do more than just fight fires.

“These organizations served as fraternal organizations as well as fire companies,” says Winkle. “The reason you joined a fraternal society in this period was things like death benefits for your family after you die, because there was no social safety net.”

One particularly striking item from the collection is a fire hat decorated shortly after the end of the Civil War for the Phoenix Hose Company of Philadelphia by David Bustill Bowser, an African-American artist, who would not have been permitted to join any of the whites-only fire companies of the era.

“It has a wonderful image of a phoenix rising from a fire,” says Winkle. “I love how the company totally bought into this classical allusion from ancient times. It's such an appropriate symbol of hope in the face of fire. [Bowser] did banners for the Union Army. And it's also a reminder of ways in which people could participate even when they weren't allowed to.”

The display exhibit “Always Ready: Firefighting in the 19th Century” is currently on view at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)