Ed Roberts’ Wheelchair Records a Story of Obstacles Overcome

The champion of the disability rights movement refused to be hindered and challenged the world to create spaces for independent living

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/55/5855de87-a600-45bc-aeeb-52ccdd8f59d1/ed-roberts-wheelchairweb.jpg)

“I am delivering to you,” said the handwritten note addressed to the Smithsonian Institution, “the motorized wheelchair of Ed Roberts.” After several dozen more ink-hewn words—words like “pioneer” and “amazing life”—the note concluded, asserting that the wheelchair told “an important story.”

And so, in May of 1995, Mike Boyd, his note in hand, pushed his longtime friend's wheelchair to the Smithsonian’s Castle, the museum’s administration building, where he intended to leave it. “You can’t do that,” Boyd heard, repeatedly, from several women—docents, perhaps—flustered by the spontaneity and lack of process. “You can’t just leave it here!” A security guard was summoned, and Boyd recalls finally imploring him, “Look, Ed Roberts was the Martin Luther King Jr. of the disability rights movement.”

Indeed, Roberts, a disability rights activist who died on March 14, 1995, at the age of 56, is hailed as the “father” of the independent living movement, a man who defied—and encouraged others to defy—the once-undisputed view that severely disabled people belonged in institutions and that the able-bodied best knew what the disabled needed.

A post-polio quadriplegic, paralyzed from the neck down and dependent on a respirator, Roberts was the first severely disabled student to attend the University of California at Berkeley, studying political science, earning a BA in 1964 and an MA in 1966, and nurturing there a nascent revolution. At UC Berkeley, Roberts and a cohort of friends pioneered a student-led disability services organization, the Physically Disabled Students Program, which was the first of its kind on a university campus and the model for Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living (CIL), where Roberts served as executive director from 1972 to 1975. Over time, from that first CIL, sprang hundreds of independent living centers across the country.

Roberts himself was a model—a joyful, positive model—of independence: He married, fathered a son, and divorced; he once swam with dolphins, rafted down the Stanislaus River in California, and studied karate.

Boyd, a special assistant to Roberts, had ferried the wheelchair from Roberts’s home in Berkeley to Washington, D.C. In the late afternoon of May 15, Boyd and several hundred other supporters had marched from the Capitol to the Dirksen Senate Office Building, pulling by a rope the empty wheelchair. A memorial service inside the Dirksen Building followed. And then, after the crowd had dissipated, Boyd and wheelchair remained—a horse, he says of the chair, without its general. He had promised Roberts that after his friend’s death, the wheelchair’s last stop would be the Smithsonian.

And it was.

Now held by the National Museum of American History, Roberts’s wheelchair embodies a story of obstacles overcome, coalitions formed and the able-bodied educated. It records a story that began in February of 1953, when the ailing 14-year-old boy, prone in a San Mateo County Hospital bed, overheard a doctor tell Roberts’s mother, "You should hope he dies, because if he lives, he'll be no more than a vegetable for the rest of his life.” Roberts, whose sardonic humor was part of his charm, was later known to joke that if he was a vegetable, he was an artichoke—prickly on the outside and tenderhearted on the inside.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/fd/7cfdc210-fce4-44b3-955b-6530682a7b65/42-65134979web.jpg)

The story continues when, several years later, his Burlingame, California, high school refused him a diploma because he had failed to meet the state-required physical education and driver training courses. Roberts and his family appealed to the school board and prevailed—and Roberts learned a thing or two about resisting the status quo.

The story continues when a University of California, Berkeley, official, hesitant to admit Roberts, said, “We’ve tried cripples before and it didn’t work.” In 1962, Roberts gained undergraduate admission to UC Berkeley—but not a room in a dormitory. The dormitory floors unable to bear the weight of the 800-pound iron lung he slept in, Roberts took up residence in an empty wing of the campus hospital.

During much of his time at Berkeley, Roberts relied on a manual wheelchair, which required an attendant to push him. Though he appreciated the company, he observed that the presence of an attendant rendered him invisible. “When people would walk up to me, they would talk to my attendant,” Roberts recalled, during a 1994 interview. “I was almost a nonentity.”

Roberts had been told that he would never be able to drive a power wheelchair. Although he had mobility in two fingers on his left hand, he could not operate the controller, which needed to be pushed forward. When Roberts fell in love and found the constant company of an attendant incompatible with intimacy, he revisited the idea of a power wheelchair and discovered a simple solution: If the control mechanism were rotated, the controller would need to be pulled backward. That he could do. On his first try, he crashed his wheelchair into a wall. “But that was a thrill,” he recalled. “I realized that, boy, I can do this.”

“That’s what the movement was about: disabled people coming up with their own solutions, saying we can build a better set of social supports, we can build a better wheelchair,” says Joseph Shapiro, journalist and author of No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement. “Disability is not a medical problem. The problem is the built environment and the barriers that society puts up. It’s not about the inability to move or to breathe without a ventilator; it’s about the inability to get into a classroom.”

There is an expression—“wheelchair bound”—that contradicts the reality of those who use wheelchairs, not the least of them Roberts. “It isn’t a device that binds us or limits us: it is an ally, an accommodation,” says Simi Linton, a consultant on disability and the arts, the author of My Body Politic, and herself a wheelchair user. “It shows a disabled person’s authority over the terms of mobility. It expands our horizons. And Ed was very much out in the world—around the globe.”

Just prior to his death, Roberts traveled the country—and the world—in a custom-built wheelchair that not only met his particular physical needs but also encouraged self-expression. “When he came into the room he captured people’s attention,” Joan Leon, a co-founder, with Roberts, of the World Institute on Disability, a think tank in Oakland, California, recalled in a eulogy for her colleague. "He kept that attention by moving his chair slightly—rolling it back and forth, lifting and lowering the foot pedals, and raising and releasing the back, even honking the horn or turning on the light.”

The wheelchair sports a Porsche-worthy, power-operated Recaro seat, which reclined when he needed to lie prone; a headlight, for nighttime driving; and a space in the back for a respirator, a battery and a small portable ramp. Affixed to one side of the wheelchair, a bumper sticker declares, in a purple type that grows bigger, letter by letter, “YES.”

“Some objects don’t immediately reference a person. With a plate or a tea cup, you don’t have to think about who used it or how that person used it,” Katherine Ott, curator of the museum’s Division of Medicine and Science, says. But Roberts’s wheelchair, she observes, bears the intimate traces, the wear and tear, of its owner—including the lingering imprint, on the seat cushion, of his body. “Who used it—and how it was used—is always hanging in the air.”

In 1998, Linton visited the Smithsonian, to work with Ott on an upcoming conference about disability. Knowing that Roberts’s wheelchair had come to the museum, she asked to see it. Ott led her to a museum storage room, and when she saw the chair, Linton began to weep: “I remember just welling up—at how beautiful the chair was and that it was empty: There was no one driving it. It was stock still, and Ed was not a still kind of guy. He was a mover and a shaker.”

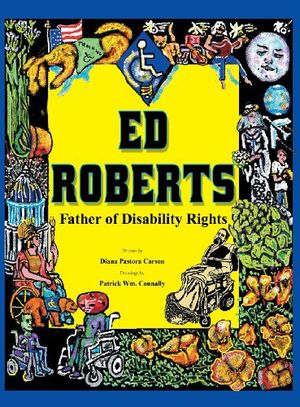

Ed Roberts: Father of Disability Rights