Artist June Schwarcz Electroplated and Sandblasted Her Way Into Art Museums and Galleries

The Renwick hosts a 60-year career retrospective for the innovative California enamelist

She began with the alchemy of enameling—the high-temperature fusing of glass and metal that dates back to 13th Century B.C.

But June Schwarcz’ art took a leap when she combined it with electroplating, an industrial process that allowed her to create singular, varied, largely abstract work over a 60-year period that was always marked with innovation.

“June Schwarcz: Invention and Variation,” a new show at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., surveys her career with nearly 60 works, some never displayed in public before.

It represents the first full retrospective of the California artist, who died in 2015.

“Though she was in pretty frail health the last years of her life, she actually made a piece the week before she passed away at the age of 97,” says Robyn Kennedy, chief administrator at the Renwick Gallery, who helped coordinate the show that was guest curated by Bernard N. Jazzar and Harold B. Nelson, co-founders of the Los Angeles-based Enamel Arts Foundation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/ee/b7ee4b20-84f9-4c30-9dd5-3a5d72dbc5df/june-schwarcz-portrait_photo-by-m-lee-fatherree-wr.jpg)

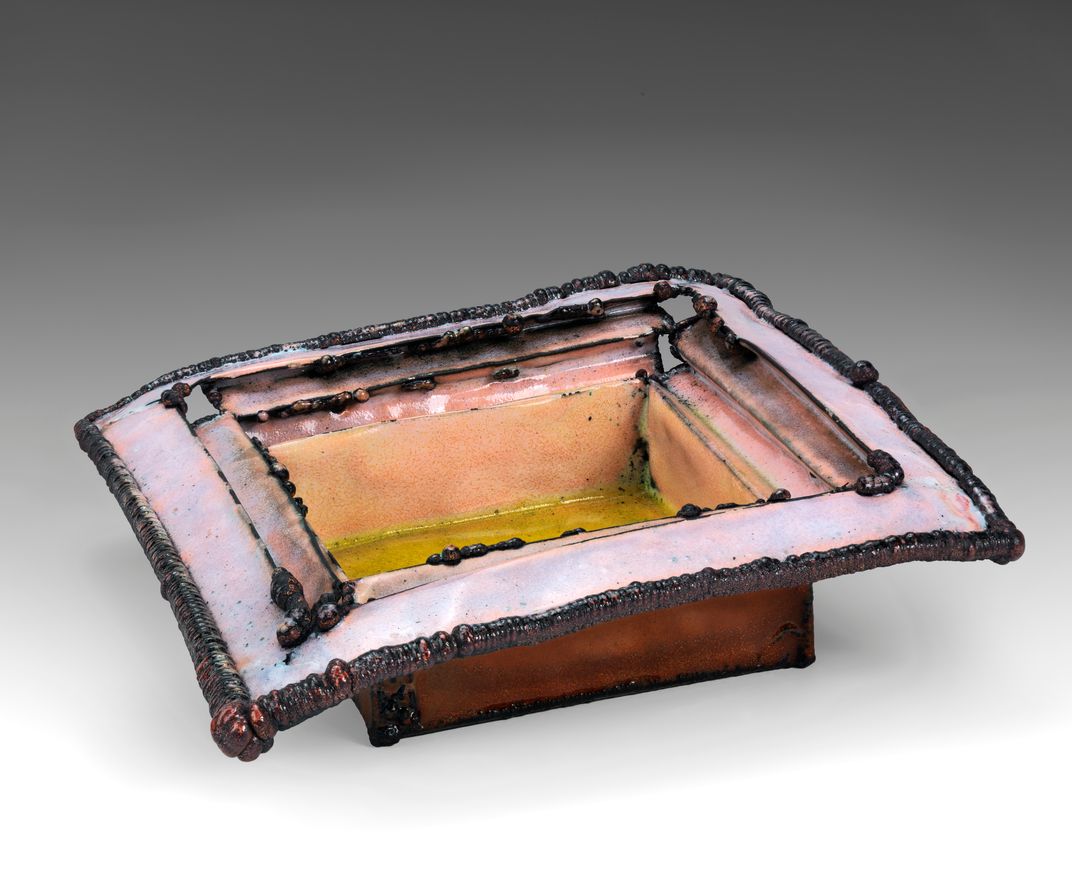

The Schwarcz exhibit will be paired at the Renwick next month with another mid-century innovator in crafts, Peter Voulkos. Both, according to Abraham Thomas, the Fleur and Charles Bresler Curator-in-Charge at the Renwick, “exuded a spirit of creative disruption though their ground-breaking experimentation with materials and process and simply by challenging what a vessel could be.”

Of her nonfunctional forms, Schwarcz once famously said, “they simply don’t hold water.”

Born in Denver as June Theresa Morris, she studied industrial design at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute and worked in fashion and package design before marrying mechanical engineer Leroy Schwarcz in 1943.

She first learned the enameling process and its power to create brilliant translucent colors in 1954.

“She took a class with three other ladies and sat around a card table and followed an enamelists’ instruction book,” Kennedy says. “That’s what really got her started.” Schwarcz mastered it quickly enough to have her work included in the inaugural exhibition at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts in 1956.

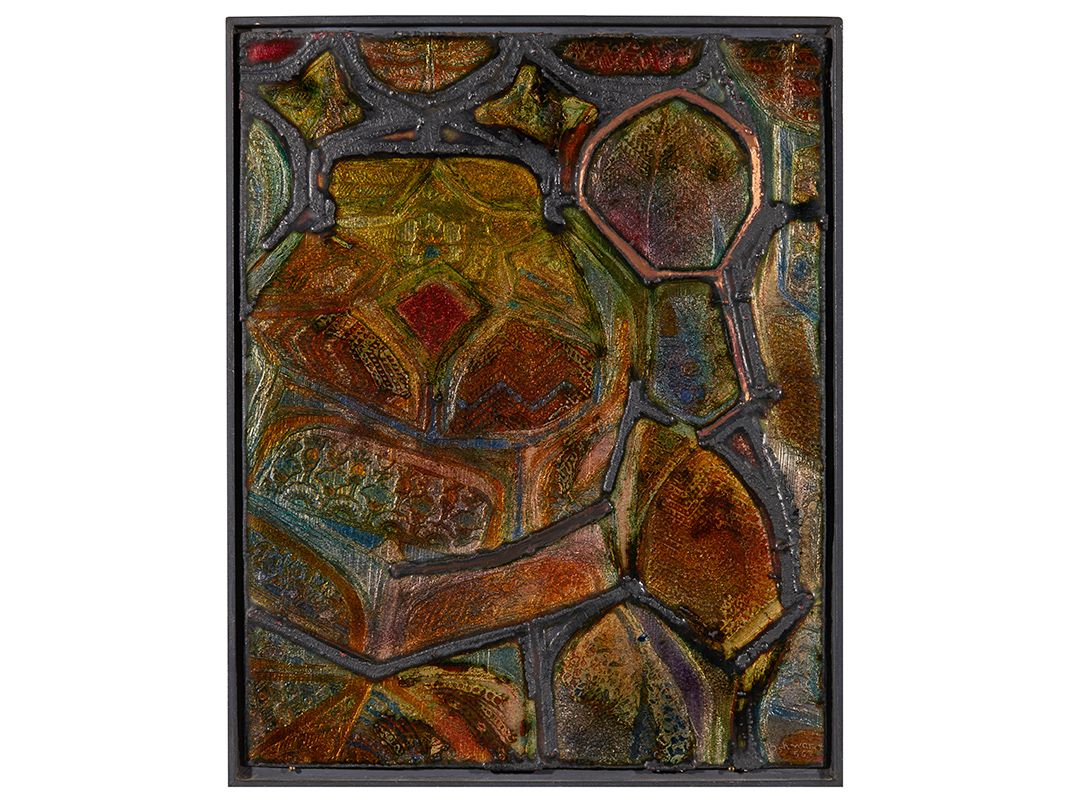

“Transparent enamel has been fascinating to me because of its ability to catch and reflect light,” the artist once said. “At times the transparent enameled surface seems to expand its boundaries . . . and to contain light.”

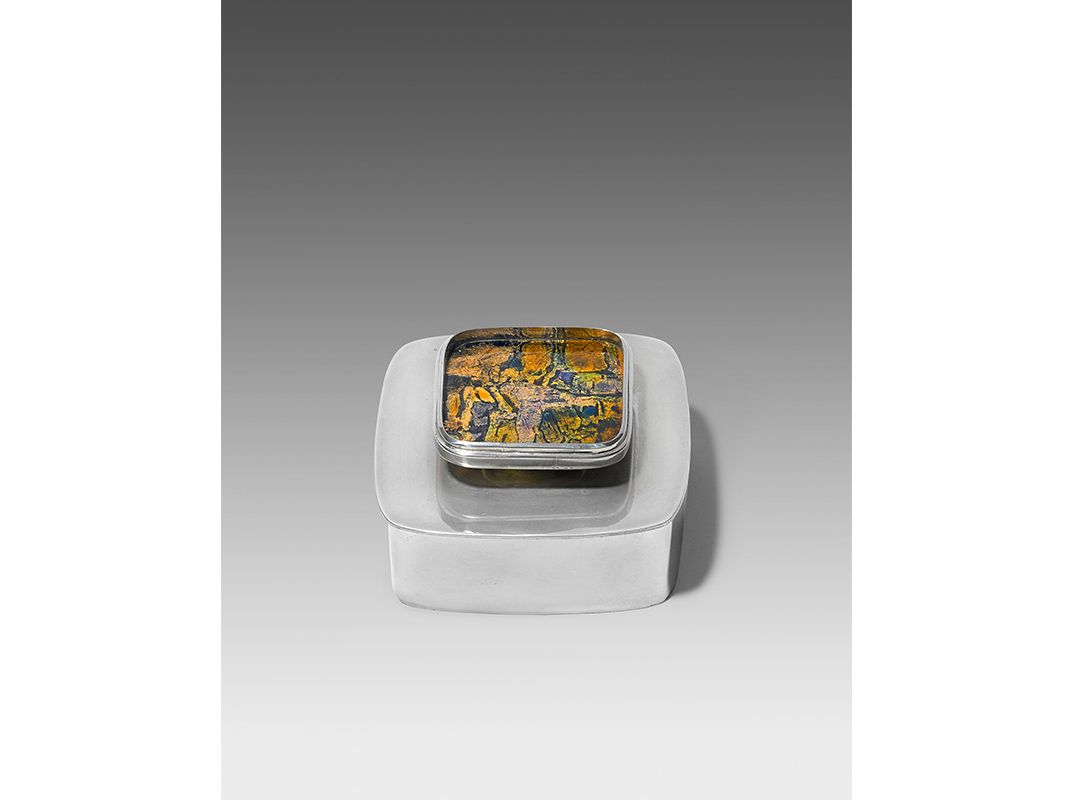

She often worked basse-taille, which involved cutting into the surface of copper plates and bowls to create complex compositions to which she added further layers of transparent enamel, and devised her own variations on other traditional enameling techniques, such as cloisonné and champlevé.

But Schwarcz was not interested in metalsmithing, Kennedy says. Indeed, “for a while she used prefabricated copper bowls to allow her to concentrate on enameling. She began experimenting with form after she began to use copper foil, which gave her more flexibility.”

The key was to work with thin enough foil that allowed her to shape and form the pieces.

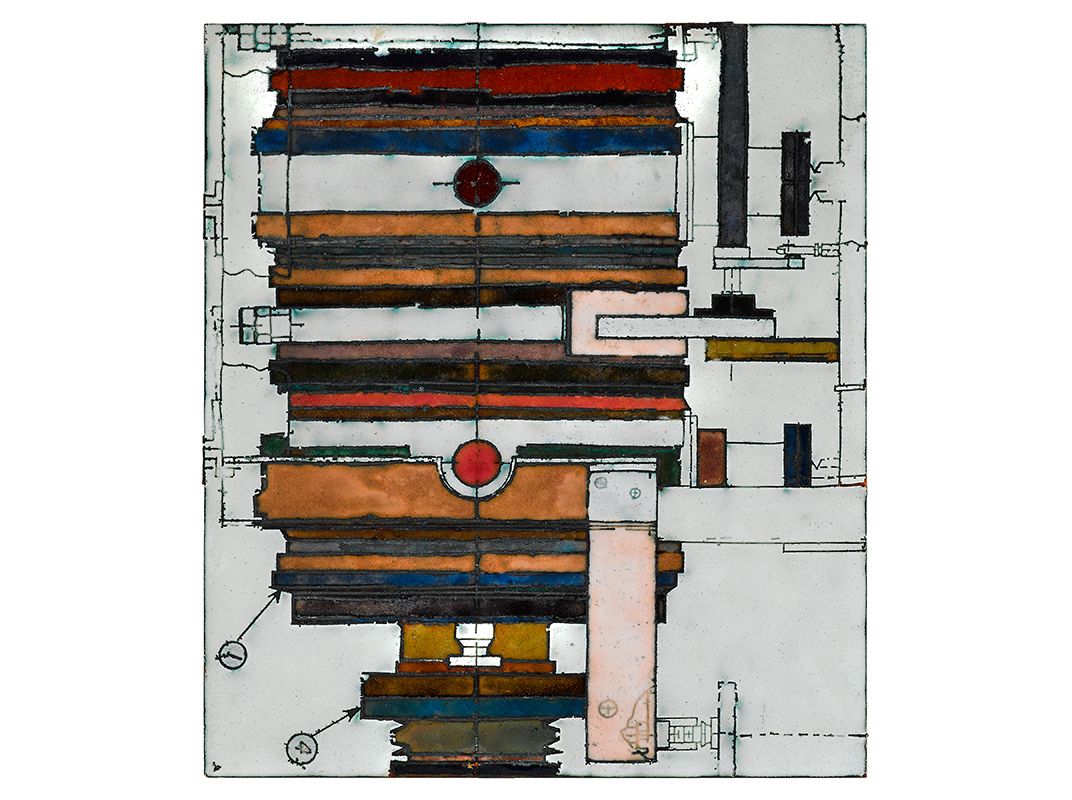

Even when learning printmaking techniques like etching, she preferred to concentrate on the metal plates than any resulting paper prints, sometime dipping the metal into acid baths to alter it further.

But the thinness of the copper plates limited her as well, so she looked into the industrial metalworking process known as electroplating in the 1960s. Pleased with its potential, she had her husband build a 30-gallon plating tank to be installed in her Sausalito, California, home studio.

It became another tool in building up portions of her work before she applied enamel color and put it in the kiln. But the constant experimentation it required became something of compulsion, Schwarcz once said.

“It’s like gambling. I go through so many processes, and I don’t know how something’s going to come out,” Schwarcz told Metalsmith magazine in 1983. “That makes the process continually exciting.”

Despite her constant experimentation and variety of results in two and three dimensions, she also upheld certain artistic traditions. They included the vessel itself. “It was been a very basic form for all mankind with a rich history,” she once said. “I like to feel a part of that continuing tradition.”

At the same time, she often paid homage to a wide variety of influences, from African and Asian design, to individual artists.

“June Schwarcz: Invention & Variation” is in many ways a stroll through art history. The 1965 Detail from Dürer has its designs taken directly from a print of the Prodigal Son by the famed 16th-century German artist—but chiefly the cross hatches on the rooflines in the background landscape.

Similarly, she lifts the swirls of dapper on a stone sculpture in France for her Art History Lesson: Vézelay.

The glowing pink and gold of Fra Angeleco inspired a series of late period vessels from a decade ago. And the Swiss-German artist Paul Klee influenced a series of black and white table sculptures.

“I love that piece,” Kennedy says of the jagged edge of Vessel (#2425), just seven-inches tall. “When you look at it in a photograph, it could be monumental. There is a lot of quality of that in her work.”

Besides the influence of art and culture, some of the works harken back to her lifelong interest in textiles. Some pieces are carefully pleated. Others have their metal surfaces sewn together to keep their shape.

“She was a very good seamstress, so she started making paper patterns for some of the metal forms,” Kennedy says. “It’s very much like a dressmaker.”

One 2002 piece, Adam’s Pants #2, was inspired by the baggy, low-riding styles being worn by her grandson, except that rather than denim it’s done in electroplated copper and enamel, sandblasted.

“Everything was available as an inspiration to her,” Kennedy says.

In her final years, long after she was named a Living Treasure of California in 1985, and around the time she received the James Renwick Alliance Masters of the Medium Award in 2009, Schwarcz turned to much lighter materials.

“When she got older it got difficult for her to work so she started to work with wire mesh,” Kennedy says, displaying her 2007 Vessel (#2331) and (#2332) as well as her more abstract Vertical Form (#2435), in electroplated copper mesh that was patinated.

“In their somber palette and assertive verticality, they posses a haunting, spectral quality that sets them apart from everything else Schwarcz produced,” Jazzar and Nelson say in the exhibition’s accompanying catalog.

Her groundbreaking work paved the way to artists who followed her in enamel including William Harper and Jamie Bennett, whose works are also in the Renwick collection, and who will speak on the influence of Schwarcz during the show’s run.

“She was considered a great inspiration by a lot of enamelists in particular,” Kennedy says, “because she just broke out of the boundaries.”

“June Schwarcz: Invention & Variation” continues through August 27 at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)