A Smithsonian Scholar Revisits the Neglected History of the Chesapeake Bay’s Native Tribes

Revisiting Indian Nations of the Chesapeake

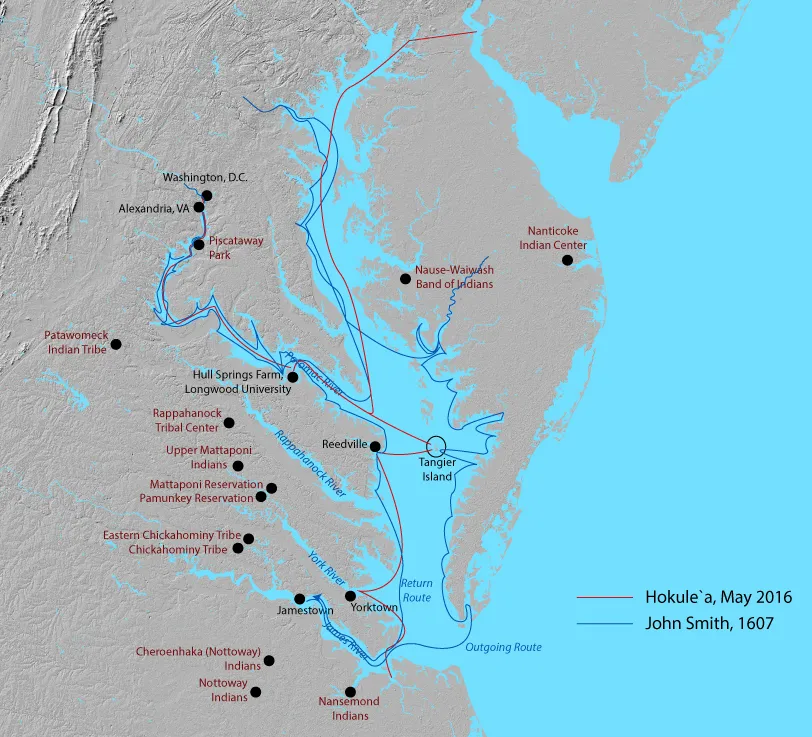

Four hundred years ago, a group of Indians greeted a ragtag group of British settlers, who proceeded to set up camp in a swampy area that became Jamestown, on the James River near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. From there, the intrepid Capt. John Smith set out twice to explore the bay. His boat was small and tublike, his crew motley indeed. But from their voyages came the first map of the Chesapeake region and descriptions of the Indians living there—as well as details about the bay itself.

Earlier this year, the crew of a Hawaiian voyaging canoe, the Hōkūleʻa, made its way up the Bay, following in the strokes of the European settlers, and like Smith and his party, were greeted by those Indians' descendants. “These Hawaiians,” said Piscataway Chief Billy Tayac, “they’re only the second ship in 400 years to ask permission to land here.”

Today, few may know of the Indians that lived in the Chesapeake region: the Piscataway, the Mattaponi, the Nanticoke and the Pamunkey—the people of Powhatan and Pocahontas who finally got federal recognition this past February. Throughout the 19th century, these native peoples were displaced, decimated, assimilated and generally forgotten. But as Hōkūleʻa docks along these waterways, they are far from gone.

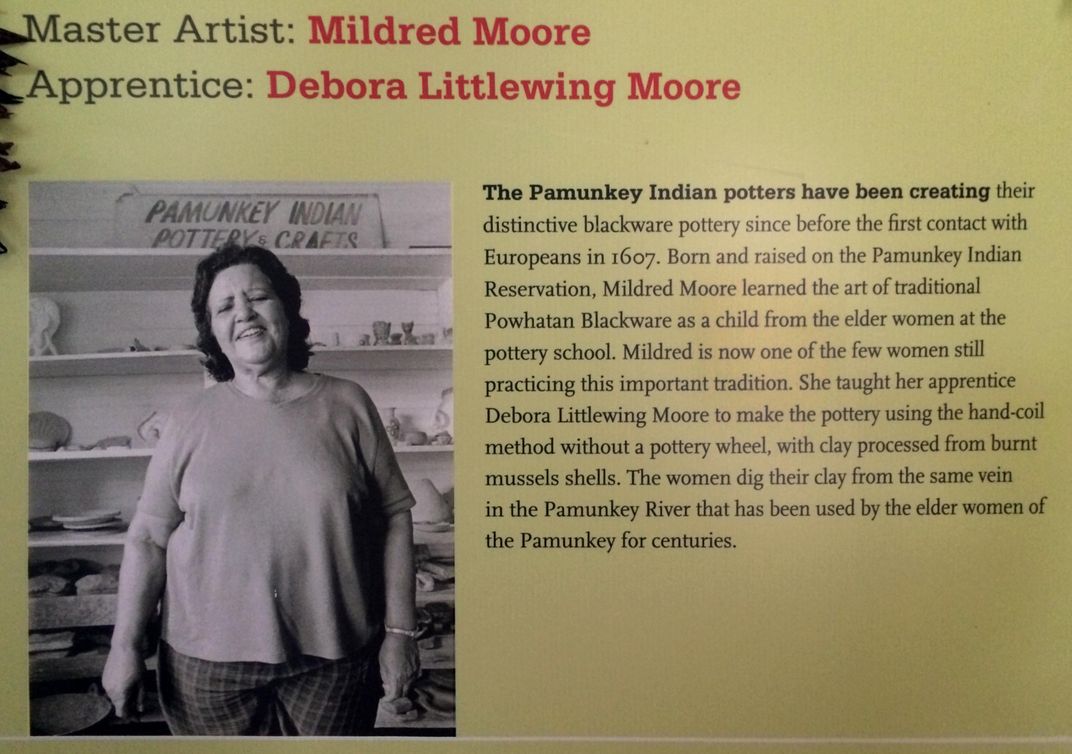

“The 1970s were rough, the 1980s were rough,” says Debbie Littlewing Moore (Pamunkey). “After the Queen of England came over to Williamsburg in 2007 for their 400th anniversary, it became popular to be Native again. It goes through cycles. But there is a whole generation that was afraid to be Indians. This is hundreds of years of historical trauma.”

The journey of the traditional Polynesian sailing vessel, which left Hilo, Hawaii, in May 2014 on its voyage around the globe, always begins at each port with a greeting first to the Indigenous cultures of whatever lands it visits.

The Indians of the Chesapeake came out in full force to welcome this floating embassy of aloha and mālama honua—meaning to take care of the Earth. I had been aboard these past eight days in my role as both voyager and scholar, observing, taking notes and learning lessons.

The Jamestown settlers were by no means the first Europeans to the bay area. In addition to two previous British attempts at settlement, Spanish explorers may have visited almost a hundred years earlier, but definitely by 1559. At the time of the Jamestown settlement, the Spanish were still declaring dominion over the Chesapeake region. But Jamestown was the first attempt at relatively successful colonization.

It may be that the Powhatan confederacy of Indians—busy with their own intertribal skirmishes—that greeted the Jamestown settlers had formed in response to a combination of threats. The confederacy included tribes from the Carolinas to Maryland. “We don't know how long that particular political dynamic existed,” says anthropologist Danielle Moretti-Langholtz at the College of William and Mary, “The documents are all from the English, we don't know the voices of Native peoples. We are heirs of this triumphal English story.”

Unlike the Puritans of Plymouth, the Jamestown settlers had come for economic reasons. Back in England, King James I laid claim to these lands, declaring British ownership. Smith’s two voyages were to search for riches—mineral wealth especially, but also furs—and to seek out a Northwest Passage around the continent. Smith failed in both endeavors. Moreover, his voyages represented a direct affront to Powhatan, the chief in whose confederacy Jamestown resided.

Chesapeake Indians were riverine communities, drawing sustenance from the waterways for as much as ten months of the year. Smith’s choice to explore by boat put him in easy contact with these peoples.

But in his wake, the English would also settle the waterways, producing goods to ship back to England. Thus began not only the removal of Indians from their lands, but also the transformation of those lands in ways that would have negative impacts on the Bay itself.

With its message of mālama honua, Hōkūleʻa seeks out stories of those who are trying to repair the damage caused by human exploitation of the environment. The largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay has suffered from 400 years of unsustainable practices.

When the canoe arrived in Yorktown, representatives of the Pamunkey, Mattaponi and Nottaway Indian Tribes of Virginia greeted Hōkūleʻa, just as representatives of two bands of Piscataway welcomed the canoe at Piscataway Park in Accokeek, Virginia, and later in May on the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia.

These were moments of ceremony—gift giving, powerful oratory and feasting. Indigenous peoples shared their legacies, their current issues and their hopes and plans for the ongoing revitalizations of their cultures—a concept they call survivance.

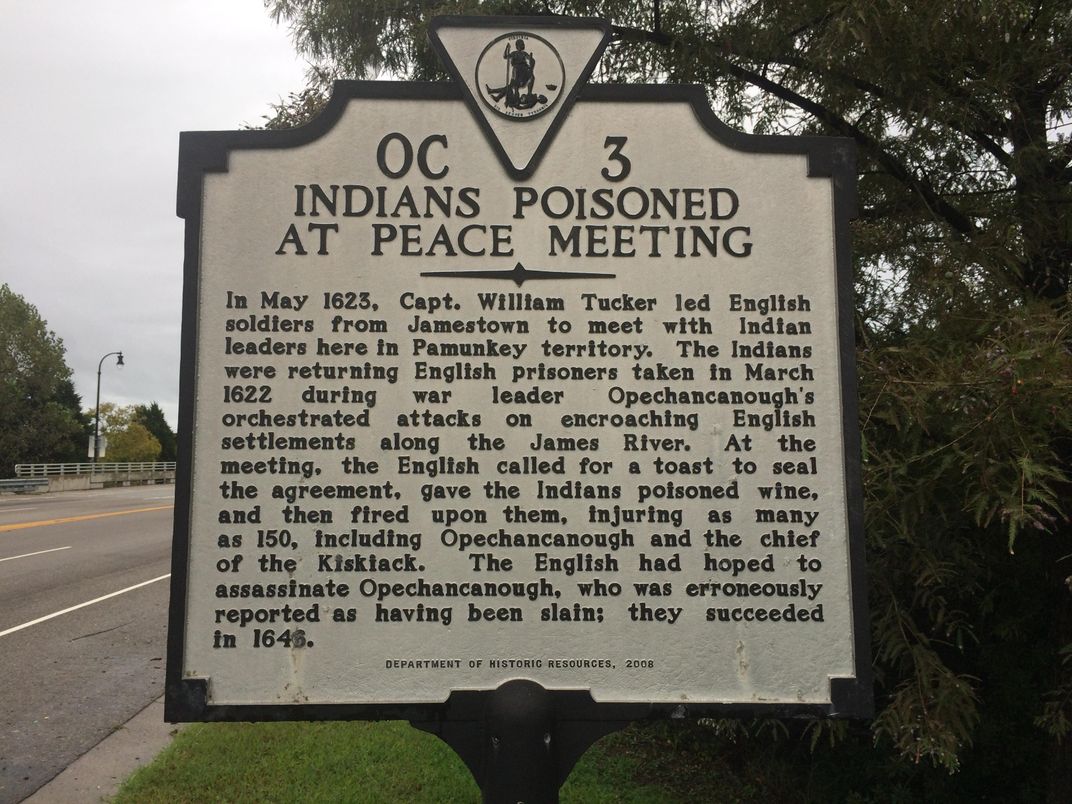

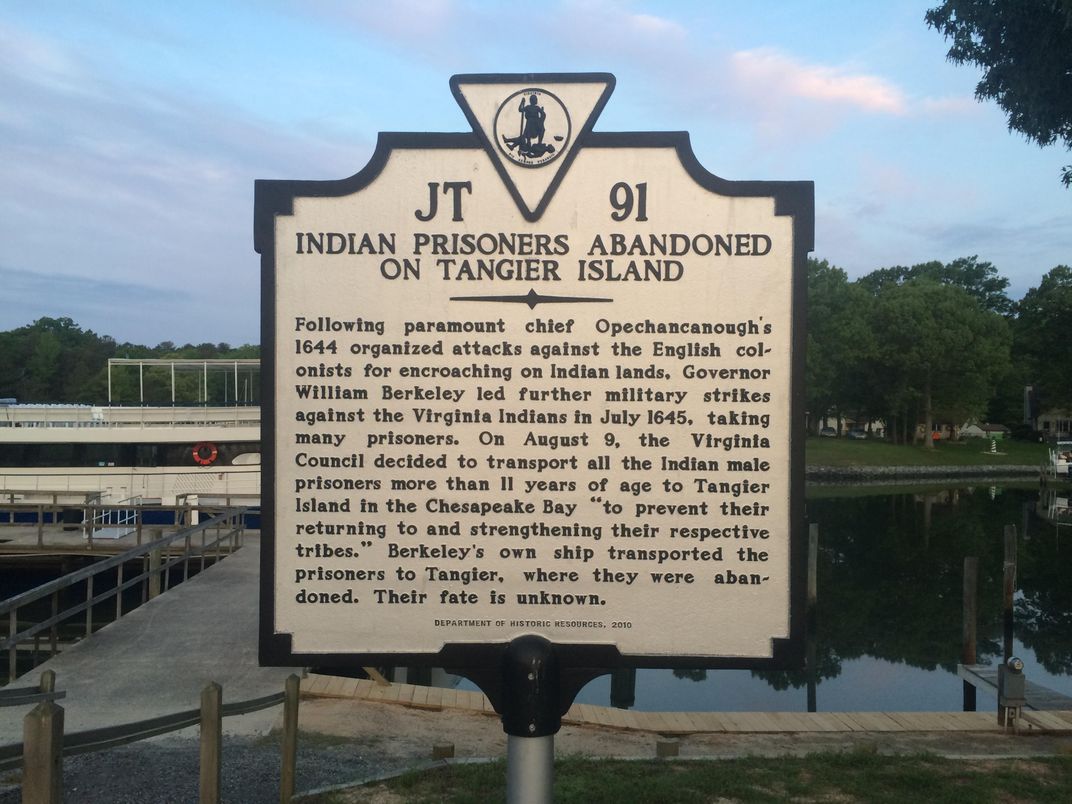

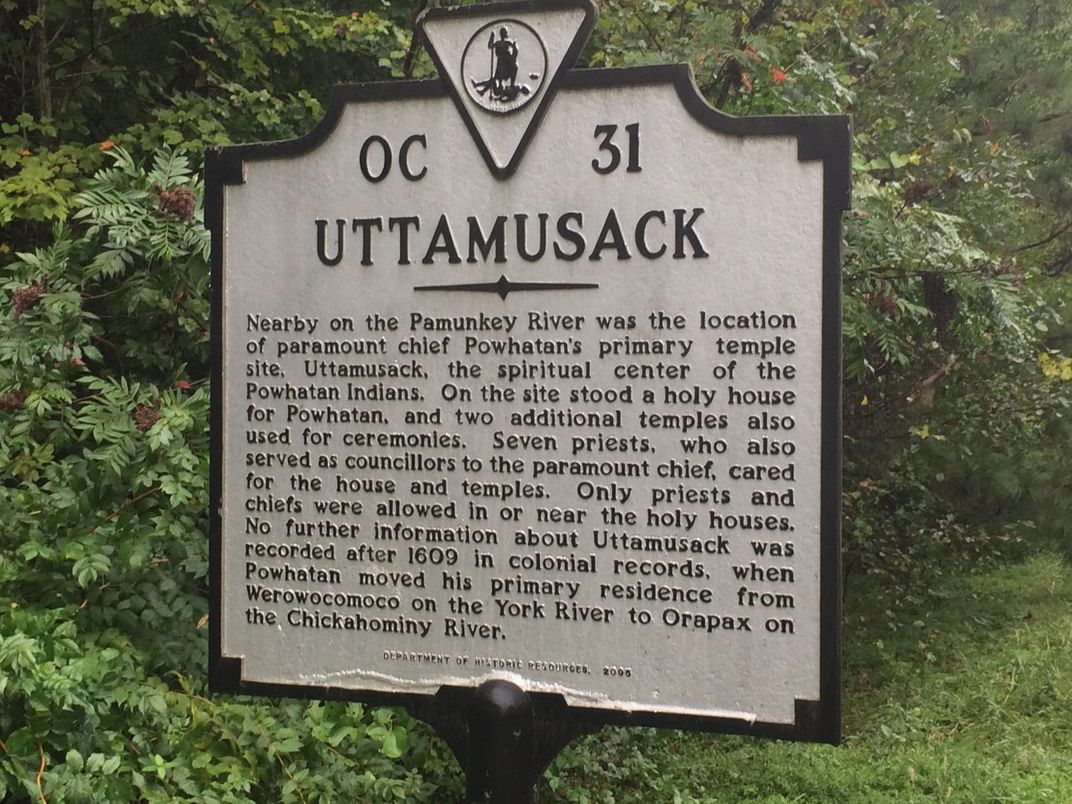

The post-Jamestown story of the Indians of the Chesapeake (and for that matter of much of the Eastern Seaboard) is lost in the textbooks. Schoolchildren learn about Jamestown and Pocahontas, but then the story stops. Though occasional roadside historical markers drop a few hints of their early story, the deep history is largely invisible.

Part of Hōkūleʻa’s impact has been to raise consciousness of these cultures and to restore their voices and their presence in the world.

British settlements in the Chesapeake during the 17th century followed the usual pattern of expansion. Indians pushed off their lands. Treaties and alliances were made, promises broken. Frontiersman pushed into Indian land at the expense of the communities.

Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 saw white indentured servants unite with black slaves in an uprising against the Virginia governor in an attempt to drive Indians out of Virginia. They attacked the friendly Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes, driving them and their queen Cockacoeske into a swamp. Bacon’s Rebellion is said to have led to the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, which effectively embedded white supremacy into law.

“By 1700, the English had settled and established plantation economies along the waterways, because they are shipping to England,” says Moretti-Langholtz. “Claiming those pathways pushed the Indians back, and the back-country Indians become more prominent. Some Natives were removed and sold into slavery in the Caribbean. This whole area was kind of cleaned out. But there are some Indians that remain, and they are right in the face of the English colonies. We can celebrate the fact that they’ve held on.”

The frontier moved away from the Chesapeake, over the Appalachians into what are now Kentucky, Tennessee and parts of the Ohio Valley, as well as the Deep South, but the plight of the Chesapeake Indians did not improve. Several lost or sold reservations they had gained, and by the mid 1800s, many were moving North to where there were more jobs. They merged with other communities—Puerto Ricans, Italians—where they could blend in, and where they experienced less prejudice.

Around the late 1800s to early 1900s, there was an attempt to reorganize a Powhatan confederacy. “The numbers weren’t strong enough,” says Denise Custalow Davis, Mattaponi tribal member and daughter of Chief Curtis and Gertrude Custalow, “and at that time, it wasn’t safe to be Indian. Because they had been so persecuted, some tribes were reluctant to come in whole-heartedly. There’s still that lack of trust.”

Perhaps the most damaging of all was the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, pushed forward by the white supremacist and eugenicist Walter Ashby Plecker, the first registrar of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics. This Act made it unsafe and, in fact, illegal to be Indian.

The law required that birth certificates identify the child’s race, but allowed for only two choices—white or colored. All persons with any African or Indian ancestry were simply designated “colored.”

Plecker decreed that Virginia Indians had so intermarried—mostly with blacks—that they no longer existed. He instructed registrars around the state to go through birth certificates and to cross out “Indian” and write in “Colored.” Further, the law also expanded Virginia's ban on interracial marriage, which would not be overturned until 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia. )Mildred Loving is often identified as black. She was also Rappahannock Indian.

Consequent to Plecker’s actions, Virginia Indians today face considerable challenges proving their unbroken lineage—a requirement necessary for achieving status as a Federally Recognized Tribe.

While many Indians simply left, the Mattaponi and Pamukey stayed isolated, which protected them. They kept mostly to themselves, not even connecting with the other Virginia tribes. But they continue today to honor their 340-year-old treaty with the Governor of Virginia by bringing tribute every year.

On the Eastern side of the bay, the Nanticoke mostly fled into Delaware, while a small band called the Nause-Waiwash moved into the waters of the Blackwater Marsh. “We settled on every lump,” said the late chief Sewell Fitzhugh. “Well, a lump is just a piece of land that is higher, that doesn’t flood most of the time.”

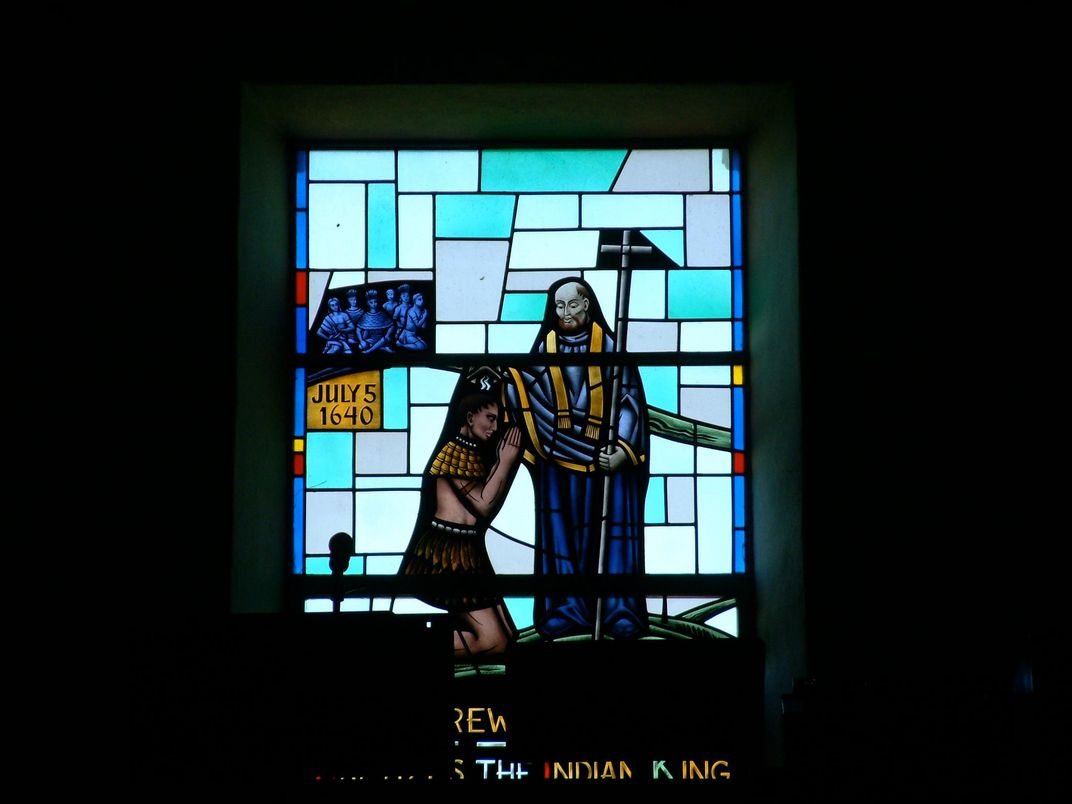

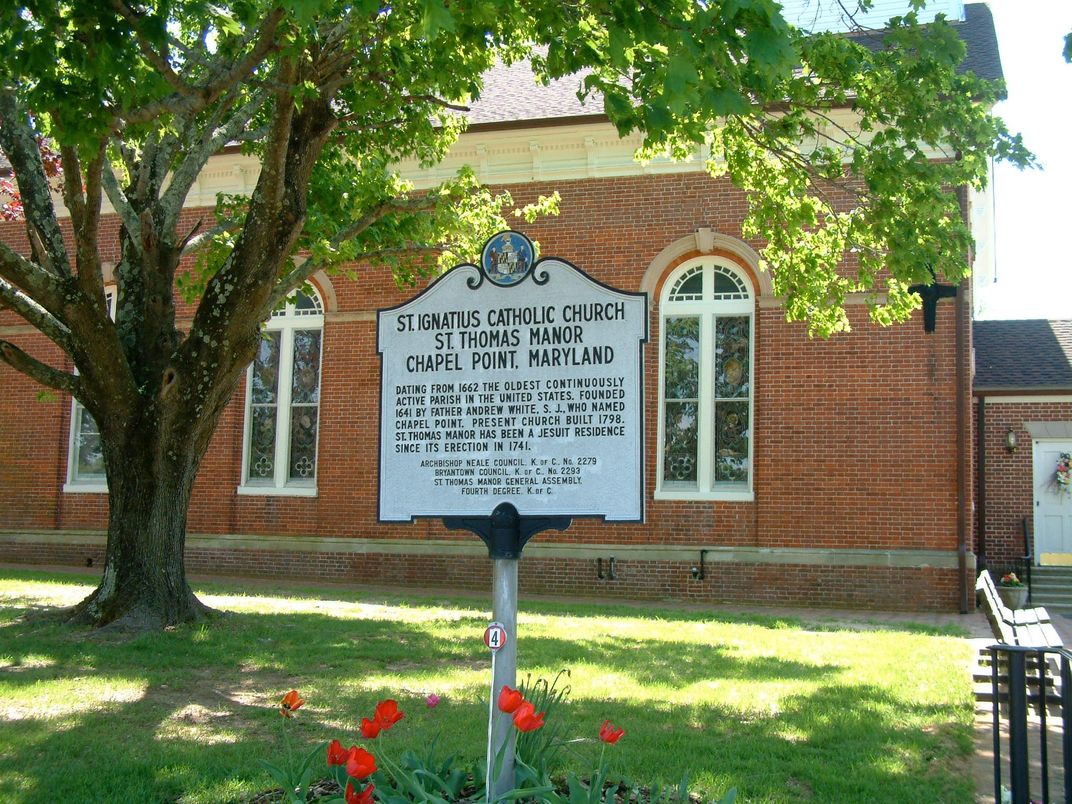

Maryland, meanwhile, was an English-Catholic colony, and the Piscataway Indians were converted. By 1620 they were settled into three reservations (or manors) under the Catholic provincial authority.

When the Protestant rebellion in England filtered across to the Americas, the Indians were subsequently maligned as “Papists.” Catholic practices were banned, and Indian manors were turned over to Protestant authorities, who did not recognize reservation boundaries and gave away parcels of Indian lands to their children. White settlement also pushed these Indians off the banks of the Potomac and upcreek to areas like Port Tobacco—an Anglicization of the Indian name Potopaco.

By the late 1600s, the Piscataway government, under the tayac (paramount chief) decided to leave the area after so much conflict with white settlers.

“There is petition after petition, speech after speech, on record by the chiefs to Maryland Council, asking them to respect treaty rights,” says Gabrielle Tayac, Chief Billy Tayac’s niece and a historian at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

“Treaty rights were being ignored, and the Indians were getting physically harassed. The first moved over to Virginia, then signed an agreement to move up to join the Haudenosaunee [Iroquoise Confederacy]. They had moved there by 1710. But a conglomeration stayed in the traditional area, around St. Ignacious Church. They’ve been centered there since 1710. Families mostly still live within the old reservation boundaries. But they also have always made pilgrimages to the old sacred site at Accokeek.”

It’s a long drive along winding country roads into the back forests of central-eastern Virginia to find the Mattaponi and Pamunkey Reservations.

One passes entrances to long driveways leading to hidden farms, expensive and reclusive estates, or people who just like their privacy. When you arrive at Mattaponi, the houses look much like anywhere else in the region, but the sense of place is different: houses are grouped together and there are no fences.

A white school building sits in the center. Virginia Indians could not go to white schools, so on the two remaining reservations—Mattaponi and Pamunkey—they had their own schools, up to seventh grade. Lacking higher education posed further difficulties. That didn’t change until schools were desegregated in 1967.

Post World War II, there was a very gradual integration into the larger economy. “I can remember when the roads were our roads, and when they were first paved. That was in our lifetime,” recalls elder Mildred "Gentle Rain" Moore, master Powhatan potter of the Pamunkey Tribe. Most people who lived on the reservation but worked off the reservation were self-employed: logging, selling fish, and fishing— not just to sell, but to feed their families. And they farmed. “When you raised a farm, you raised a farm to feed you through the summer, can food for the winter and into the spring, until you could start fishing again.”

“We never starved, we always had plenty of food” says Moore. “Daddy never let us go hungry. He had a garden, he used to fish, hunt. There was no store on the reservation. We used to have to walk down the railroad tracks for about a mile or more to go to the store.”

As for working in local industries, Denise Custalow Davis says, “They may employ you, but if they find out you’re from the reservation—because you might not look Indian—suddenly they don’t need you anymore.”

**********

Hōkūleʻa’s impact in the Hawaiian Islands, back when it first sailed to Tahiti in 1976, was to prove to all Oceania that contrary to much of Euro-American scholarship, their ancestors had indeed been great navigators, voyagers, adventurers, who colonized the largest ocean on Earth. And it is that spirit of pride for Indigenous peoples that the canoe brought to the Chesapeake.

“For me it was about our cultures,” says Debbie Littlewing Moore, who helped organize the Yorktown event. “There’s such a large distance and difference between us and Hawaiians, but also similarities, and now this generation has the opportunity to preserve their native cultures. Out West, our brothers and sisters have been feeling the worst aspects of colonization and assimilation for the last 200 years. Here it has been the last 500 years.”

“Hawaiians have held onto their culture so strongly, they still had elders teaching them,” she adds. “Here, my elders are gone. So it was a breath of fresh air to see these people who are revitalizing their culture so strongly. It was one of the best memories I have, for the rest of my life. Their energy was so beautiful.”

In the next article, we learn what the Mattaponi and Pamunkey are doing to help restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay—to mālama honua.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/d1/20d1aa77-cb4d-4448-96a6-7b84a3a86e5d/king__queen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)