“Freakish Absurdities:” A Century Ago, An Art Show Shocked the Country

The Armory Show provoked reactions of love and hate; today it is recognized as changing American art forever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130215074041Bathers-thumb.jpg)

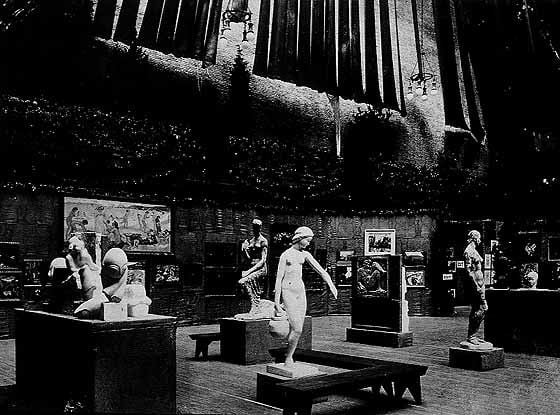

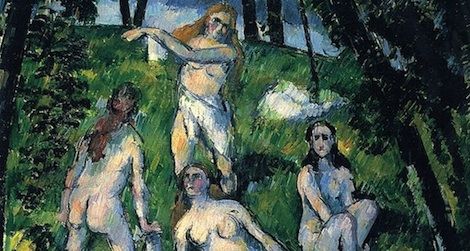

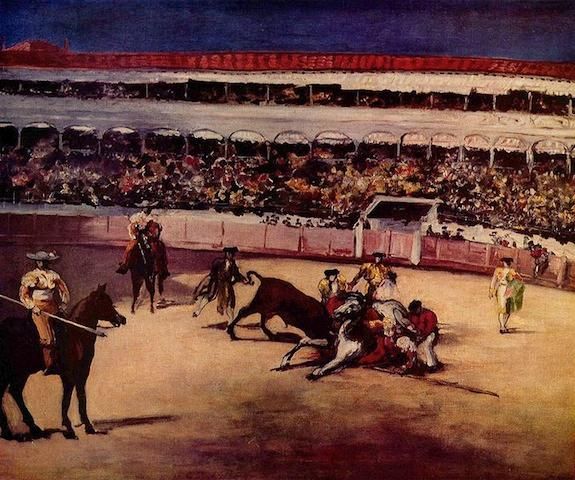

Posters advertised a heady guest list for the 1913 Armory Show held in New York City, including, Matisse, Brancusi, van Gogh and Cézanne. It would have been a once-in-a-lifetime gathering had it been true and not just a little bit of ornery fun on the part of organizers (unfortunately, van Gogh died in 1890 and Cézanne in 1906). Even without them, the show, which celebrates its 100th anniversary February 17th through March 15th, managed to make history.

“Going to the Armory Show is kind of like going to a sideshow,” explains Mary Savig, a specialist from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. Organized by artists Walt Kuhn, Walter Pach and Arthur B. Davies the show, which featured some 1,250 works of art from both European and American artists, is seen as the moment modern art took center stage in the United States.

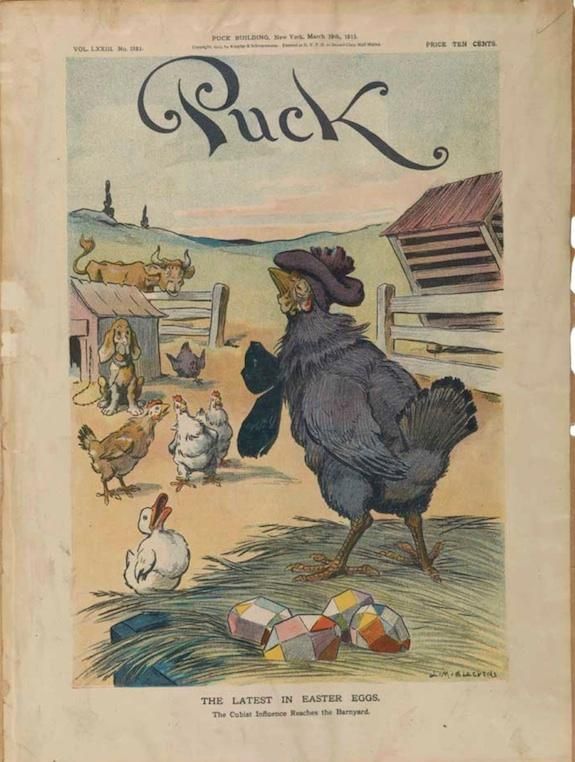

Everything from Impressionism to Cubism was included, sometimes to comical effect. Critics weren’t quite sure what to do with the radical new vision of art on view, particularly when it came to French artist Marcel Duchamp’s enigmatic Nude Descending A Staircase. Audiences and critics alike became obsessed with what they thought must be an optical illusion or some sort of visual trick. Savig says, “There was this rhetoric in the newspapers formed around the idea that you would go and you would look for this woman in the painting and was she there? People couldn’t figure it out.” One critic in Chicago even held a very serious lecture trying to highlight precisely where the figure of the woman could be delineated. (For more about Duchamp and his painting, check out Megan Gambino’s document deep dive with materials from the Armory Show)

The New York Tribune declared it a “Remarkable Affair, Despite Some Freakish Absurdities.”

Other reactions were less kind. The International News Service published a cartoon by Frederick Opper that purported to explain art from the exhibition in four panels, including the room featuring “work by ‘nuttists,’ ‘dope-ists,’ topsy-turvists,’ ‘inside-outists’ and ‘toodle-doodle-ists,’ whom police are now trying to locate” and a dotted line which showed the “route taken by Old Masters after seeing advanced art exhibits.”

“That was also to the credit of the organizers of the show,” says Savig, “because they really wanted it to be sensational. They were really hoping to get these headlines that would grab people in to see for themselves what kind of unimaginable artwork was on exhibit.”

Savig, who curated the exhibit, “The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913,” set to open at the Montclair Art Museum on Feb. 17, 2013, says that the show was also a personal mission on the part of the organizers. “ wanted American art to be equal to or eventually surpass the European works in the show. He really wanted. . .to show how avant-garde Europe was. But also, to show, hopefully, that Americans could also be at that level.”

Along with her colleague Kelly Quinn, who created an interactive, online timeline about the planning and execution of the Armory Show, Savig relied on the Archives of American Art’s extensive materials to get the behind-the-scenes stories. Kuhn’s letters back home to his wife, Vera, for example, detail his time spent scouring Europe for material to take back for the show. Writings from artists who volunteered at the show exclaiming over the inspiring works of art offer a personal testimony as to the impact the show had on the course of American art. And tiny details like a letter from a rabbi who lost his umbrella while attending the show, reveal, says Savig, the wide appeal of the show and the audience the exhibit was able to attract.

One example of the kind of passion the show could encourage comes from artist Manierre Dawson, who desperately wanted to buy some of the art on view. “There’s these really sweet pieces of his father saying that he can’t buy the Picasso because it would be outrageous to hang above the mantle and that really it would be better for him to spend his money elsewhere,” says Quinn. “But he had saved his money and he ends up buying a Duchamp drawing. He kind of consoles himself and says, it’s almost as big and almost as good as Nude Descending a Staircase.”

The show traveled to Chicago and Boston after New York. Despite requests from Baltimore, Des Moines and Seattle, the organizers only completed a three-city tour before getting back to their own art. But that was enough to accomplish the goal Kuhn and the others had set out for themselves: to revolutionize art in America.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)