A Host of Relics from Lincoln’s Last Days All Came to Reside at the Smithsonian

The Lincoln collection at the American History Museum marks the horrific tragedy and the poignancies of a nation in mourning

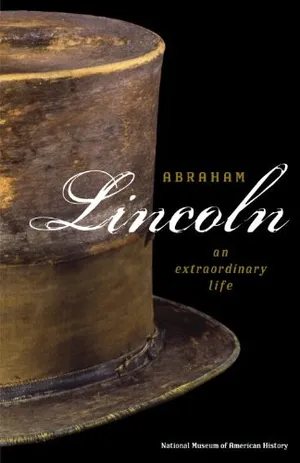

Abe Lincoln's hat, the famous stovepipe that made a tall man taller, became his trademark and also his briefcase.

The day he stood outside the Capitol to make his first inaugural address, he took his hat off and looked about for a place to put it, and when his erstwhile political rival, Senator Stephen Douglas, reached out to hold it for him, it was seen as a gesture of unity within the fracturing Union. On a special train to Gettysburg in late 1863, chattering generals and officials so distracted the president that he stopped laboring over the speech that he would deliver at the soldiers' cemetery, and stuck it back in his hat. When he took it out later, completed and delivered it, the newspapers hardly noticed, but those 272 words will never be forgotten.

The hat and his height identified him from afar, a towering figure that was surely an asset in politics and among military men, but so conspicuous that it also made a tempting target. We do not know whether he wore it in 1864 as he stood on the parapet of Fort Stevens watching Jubal Early's approaching Confederate invaders, but it's easy to imagine that a particular Rebel sharpshooter was actually aiming at the president when he seriously wounded the army surgeon standing beside him.

One summer night, according to an infantryman guarding Lincoln's retreat at the Soldiers Home, the hatless president came galloping up in a hurry. Lincoln said a gunshot had sounded in the darkness and spooked his horse. He doubted that the shot was meant for him, but the soldier wrote that when he searched down the road he found the missing hat, with a bullet hole through the crown.

Like the president's hat, his pocket watch went with him everywhere, as he checked off the station stops on his way from Springfield, as he sat for anxious hours in the telegraph office, waiting for news from Shiloh, Cold Harbor and all the places where so much American blood was spilled. Sitting in that office, he dipped a pen into the inkwell and wrote a first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as dispatches praising and admonishing generals in the field.

The hat, the watch, the inkwell, a desk he used in Illinois, the shawl that he draped about his shoulders as he paced worrying to and from the War Department, a coffee cup that must still bear his fingerprints—and then the artifacts of his fate, the actress's blood-stained cuff, the surgical instruments, the funeral pall, the drum that paced that final solemn procession, the mourning watch that Mary Lincoln wore the rest of her days—mute as they are, these tangible fragments of his life and death speak to us almost as eloquently as his immortal words.

The Lincoln Collection at the National Museum of American History got its start sometime in 1867, the actual date is unknown, when the United States Patent Office delivered the president's top hat and his chair from Ford's Theater to the Smithsonian Institution. The Secretary ordered the items crated and stored in the basement of the Smithsonian Castle building. The chair was eventually returned to the theater. The hat, however, remained hidden away for the next 26 years, but according to curator Harry R. Rubenstein, it was the first of a collection that "grew slowly and without much curatorial direction, other than the goal of preserving anything associated with the martyred president." Rubenstein's book, Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life details the stories behind this unparalleled collection of more than 100 artifacts that were donated by family members, close friends and associates of the Lincolns.

Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/c4/4fc44a69-4061-4a57-8da3-f956f82f58f1/lincolnsuitweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/cf/0ccfcfdf-0eb8-48ea-8a4b-06aa285fdc42/20086462web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/d5/37d58ebf-48d8-4eca-a046-cc515805eca8/emancipationproclamationinkstandweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/cc/b3cccdd9-fd72-468a-a6dc-62dc9208a21f/200810492web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/b7/8fb754ef-6877-4f53-bff9-b491220e3fe3/200810490web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/3f/453fc8d7-d96a-45ab-a78b-afa50128d58c/20086463web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)