How the Artist Behind the Giant Landscape Portrait on the Mall Used a Super-Precise GPS Satellite System as a Paintbrush

To create the National Portrait Gallery’s “facescape,” artist Jorge Rodríguez-Gerada got some high-tech help

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/f5/d1f59613-7bb7-4007-8f6b-c0b748a03446/satout_of_many_one_wash_dc_ge1_6oct2014_a.jpg)

There are many uses for Global Positioning Systems (GPS)—in cars, computers, phones—but it seems the first time an artist has used this kind of technology to make art in America is happening right now on the National Mall between the Lincoln Memorial and the World War II Memorial.

Earlier this year, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery commissioned Jorge Rodríguez-Gerada, a Cuban-American artist, to create a giant earth portrait, a “facescape,” on a 900-foot by 250-foot plot on the Mall. A team installed 15,000 pegs, or stakes, in the ground, and the next step is to thread the stakes with string, in order to create a template for the placement of the soil and the sand, forming the light and dark facial features of the portrait.

To position the stakes, Rodríguez-Gerada enlisted the help—for free—of Topcon Positioning Systems, Inc. of Livermore, California. “Topcon technology is my digital paintbrush,” the artist says.

The average GPS used on our phones is relatively inexpensive, but not extremely accurate. Using the GPS satellite systems and its own special components, Topcon does super-precise “GPS+” surveying for agribusiness, private commercial construction companies, cartographers and government agencies (including the U.S. Army and Navy).

“To take just one example, farmers need exact locations to put down seeds, spray pesticides or build routes for tractors,” says Scott Langbein, the director of product marketing at Topcon. “We show them how to do that—and save them time and fuel.”

Now the company has volunteered to help with a piece of earth art.

Rodríguez-Gerada spent this summer creating a composite drawing of the faces of 50 young Washington, D.C. males in order to make his landscape portrait. Then he gave the final artwork to Topcon.

“What we did was to bring his image into the digital world and scaled it from the drawing, using the same techniques we would use to build a road or a bridge,” says Mark Contino of Topcon, who has worked with the artist on this project from the beginning. “A month ago we did a construction surveying program.” Essentially, Topcon was mapping the portrait on the site.

“We use the same GPS signals, but we use a lot more and better high-precision components,” Contino explains. “If you are building a subdivision in a field, for example, first you locate trees, hills and streams. This information goes back into a CAD program in your computer so the architects and engineers can design a digital map for the subdivision that goes back into the field. Someone then has to follow that survey to put stakes in the field to indicate where the roads will go.”

“We used the same technology for Rodríguez-Gerada’s project,” he continues. “We created a series of vector lines, using XYZ coordinates of the art work on latitudinal and longitudinal axes. We have a fixed base station on the site that sends out a GPS correction signal every second.”

The Clark Construction Company, which will actually move the dirt and sand to create the image on the ground, has 22 volunteer field engineers to do the mapping before the earth moving. Topcon trained each in less than a day on how to use its precision GPS receiver called a HiPer SR in receiving the signals from the base station. It is a unit the size of a salad plate that is mounted on a pole.

The volunteer takes a HiPer SR and a computer with him to the site to locate the precise locations to hammer the stakes into the ground. The HiPer SR receives signals from the base station every second, with instantaneous corrections. As each volunteer walks around with his HiPer SR and computer, he can find, to within half an inch, the exact spot to place a stake.

Whereas the GPS on a phone is accurate only to within 30 feet of a destination, Topcon, by utilizing advanced GPS techniques with the HiPer SR, can locate the spot to within a pinkie’s width.

“If you think of the earth as a big piece of graph paper, we are the pencils,” Contino says. “We make the marks on the paper, and all of a sudden you see the shape emerge as we put more and more points down. We use our technology to take the design out into the real world.”

Incredibly, it will take Clark’s 22 field engineers fewer than 10 days to place more than 8,000 “mapping” stakes on the 6-acre site. Now that is science in the service of art.

Related Books

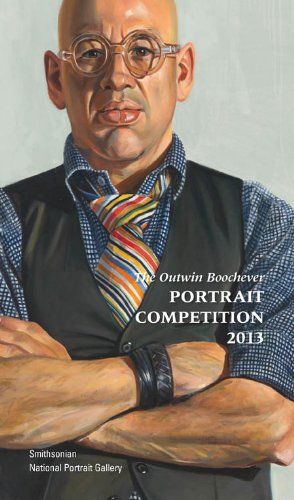

Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition 2013

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)