How Countless Hours of Live Jazz Were Saved from Obscurity

The Savory Collection breathes fresh life into jazz

When Loren Schoenberg visited the hamlet of Malta, Illinois, in the year 2010, he knew not what he’d find. What he discovered—stashed away in boxes that had lain dormant for decades—was a remarkable collection of sound recordings that would prove to shake the jazz world lock, stock and barrel, and would command the fervent attention of Schoenberg and Grammy award-winning audio restoration expert Doug Pomeroy for the next half-dozen years.

Schoenberg, founding director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, a Smithsonian Affiliate, has spearheaded the effort to bring this motherlode of live jazz to the ears of consumers across the country via a staggered series of album-size iTunes releases. Volume I, “Body and Soul: Coleman Hawkins and Friends,” hit the iTunes Store this September. The second volume, featuring a host of classic Count Basie cuts, is slated for release on December 9.

The entire collection was the property of a man named Eugene Desavouret, son of the prodigious, idiosyncratic sound engineer William “Bill” Savory.

Savory, who in the 1930s found gainful employ at a so-called transcription service—one of many dedicated to recording live jazz tunes off the radio for networks using top-of-the-line technology—rapidly amassed a personal music collection par excellence.

Staying after hours each night, Savory would cut himself custom records chock-full of vibrant swing and heartbroken blues. In his time with the transcription service, Savory forged many a personal connection with the musicians of the day, each of whom thrilled to learn of his exclusive, masterful renderings of their on-air displays.

“He’d take them down to [Benny] Goodman or [Count] Basie or the others,” Schoenberg recalls, “and say, ‘Hey, I recorded your broadcast last night.’ He became friends with [them], and that’s how it all happened.”

As fate would have it, Schoenberg, who himself fondly remembers playing alongside Benny Goodman, Ella Fitzgerald and others, would come into contact with Savory half a century later, in the 1980s. Schoenberg had long been an admirer of the five Benny Goodman LPs Savory had released in the 1950s, discs he viewed as the gold standard in recording quality—“much better than the studio recordings,” he tells me, “and much better even than the famous Benny Goodman Carnegie Hall concerts.”

Upon meeting Savory in person, Schoenberg posed him a single question: “How did you pick the best of everything you had?” Schoenberg wryly recounted Savory's response: “I didn’t pick the best of everything I had. I picked the best of what was in the first box!”

At this point in the narrative, Schoenberg was beyond intrigued. For decades after he dogged Savory, imploring the audio maestro to allow him access to more of his apparently copious never-before-heard jazz records. Savory, however, was a tough nut to crack.

“I never got to hear it,” Schoenberg lamented. Not during Savory’s lifetime, at least.

Fortunately, six years after Savory’s passing, his son—Desavouret—agreed to let Schoenberg take a look at the collection at last. He was expecting something good, of course, but what he found was truly astonishing:

“Imagine my surprise when it was Count Basie and Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald and Coleman Hawkins,” Schoenberg says, pure glee in his voice. “I went back out the following week with my board chairman, and he graciously underwrote the museum acquiring the collection.”

Acquiring the collection, though, was merely the first step. Next on Schoenberg’s agenda was converting the music—several hundred hours’ worth—from vinyl to high-fidelity digital files. “[Doug Pomeroy] and I worked very closely together for years to digitize the music, and to equalize it,” Schoenberg explains—all the while taking care not to, as he puts it, “lobotomize the frequencies.”

Now, a kiosk at the National Jazz Museum offers listeners from all across the globe unfettered access to the full array of tracks Bill Savory captured all those many years ago. Not only that, but the museum intends to publicize the Savory Collection on iTunes in a series of “albums,” arranged by Schoenberg and uploaded seriatim.

The first album, titled “Body and Soul: Coleman Hawkins and Friends,” includes with the songs a colorful, photo-filled liner notes packet that explores the significance of the various tunes as well as the artists who brought them to life. Additionally, the album is graced with scene-setting introductory remarks by renowned “Jazz” documentarian Ken Burns.

Kicking off the music is an extended version of Coleman Hawkins’s immortal “Body and Soul,” in which the pioneer’s virtuosic tenor saxophone skills are on full display. Schoenberg describes the song as “the first chapter of the Bible for jazz musicians.” Little wonder, then, that its release as a Savory single earlier this year drew the attention of jazz researchers and enthusiasts the world over.

The slick tonal turns of phrase of “Body and Soul” segue smoothly into the inflected, conversational vocals and easy cymbals of “Basin St. Blues,” which in turn give way to the gentle, down-tempo strains of “Lazy Butterfly.” The sequence is punctuated with jocular commentary from a period radio announcer.

After this opening trio of Hawkins tunes comes the exuberant, upbeat brassy number “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” in which Ella Fitzgerald’s sharp, spunky vocals take the helm (“Oh dear, I wonder where my basket can be?”). Following is Fitzgerald’s “I’ve Been Saving Myself for You,” a sultry complement with prominent piano flourishes.

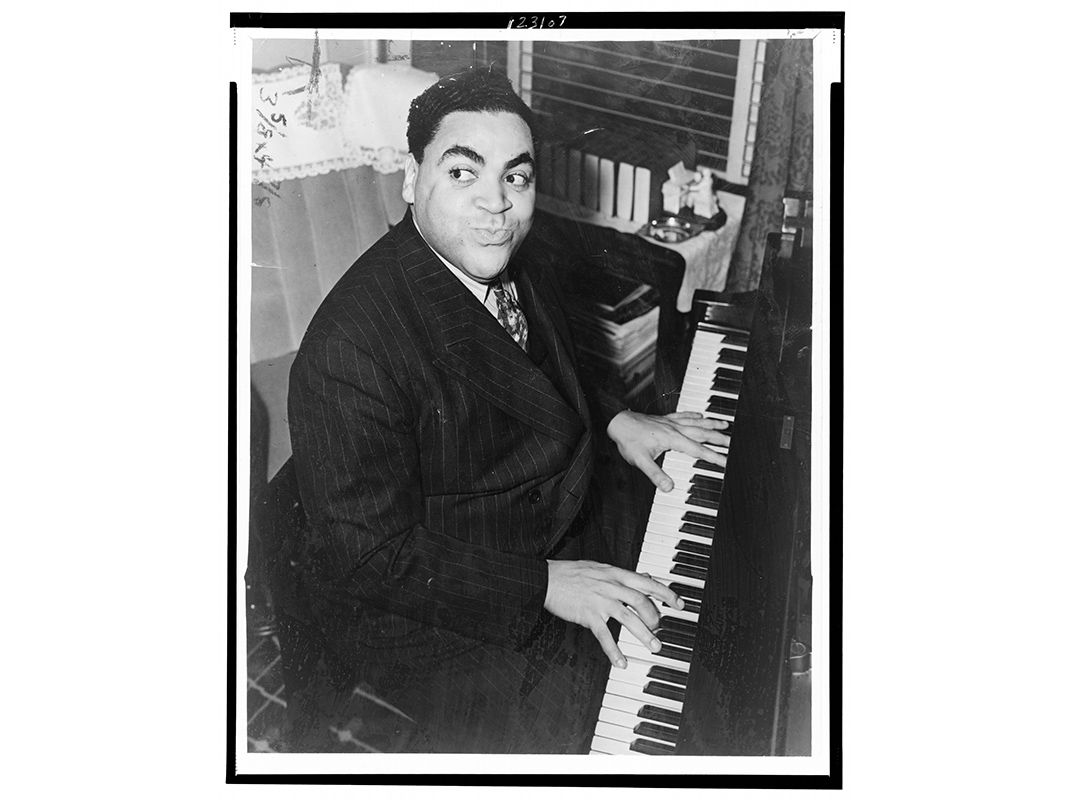

The midsection of the album is devoted to fun-loving Fats Waller and his Rhythm. The persistent bass beat of “Alligator Crawl” simulates the heavy footsteps of the title reptile, and Waller’s intimations of “fine etchings that will surely please your eye” in “Spider and Fly” are playfully suggestive and sure to entertain.

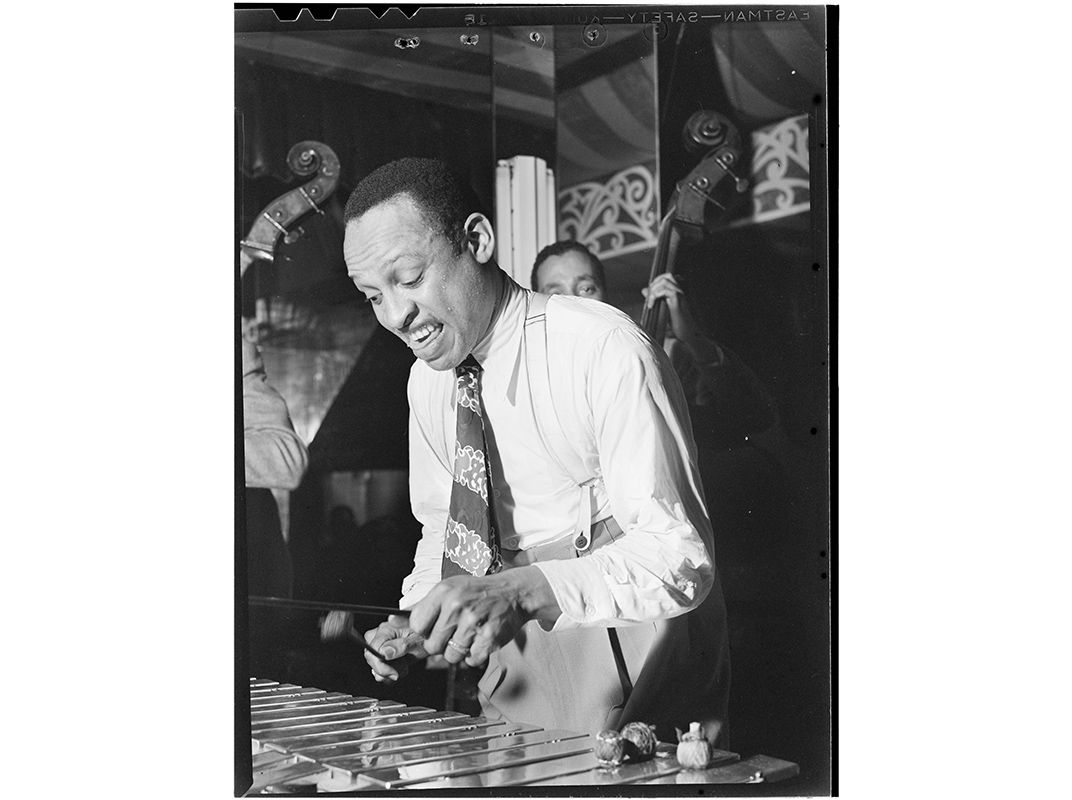

Waller’s sequence, six tracks in all, precedes a Lionel Hampton run of roughly equal length. The extemporaneous intermingling of xylophone, sax and horns in a jam-session recording of “Dinah” provides a breath of fresh air to the listener, and the machine-gun piano of “Chinatown, Chinatown” evokes a pair of dancers twirling impossibly across a dance floor.

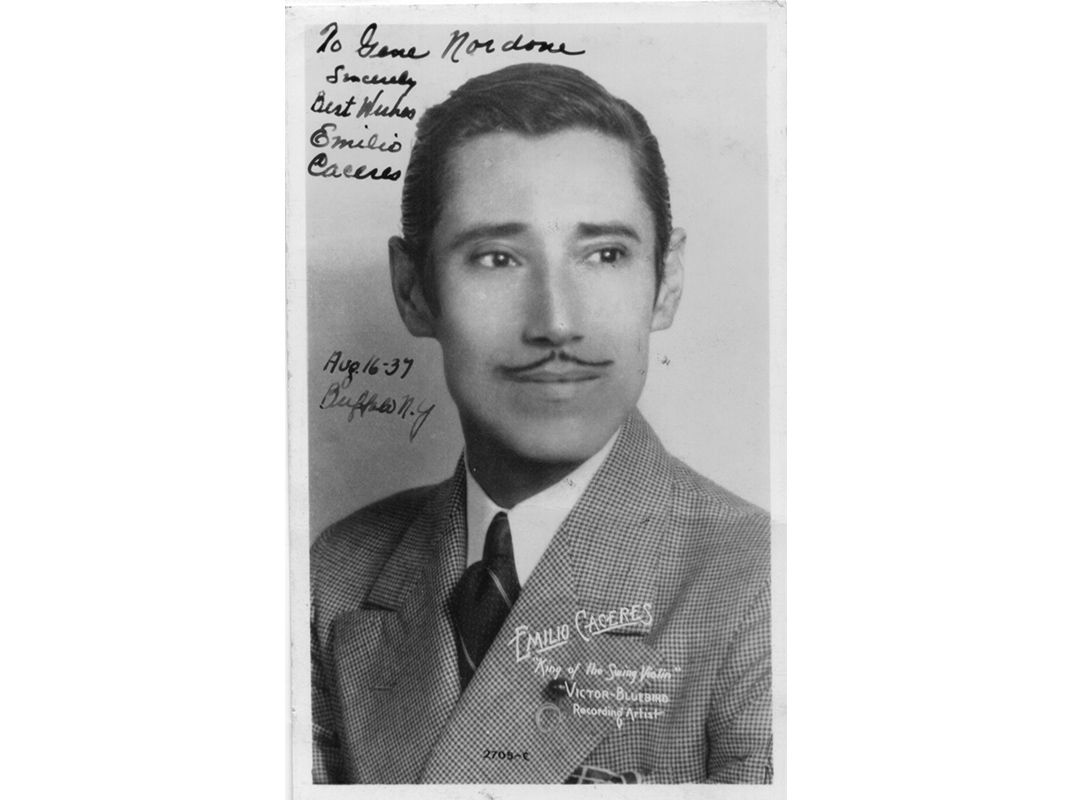

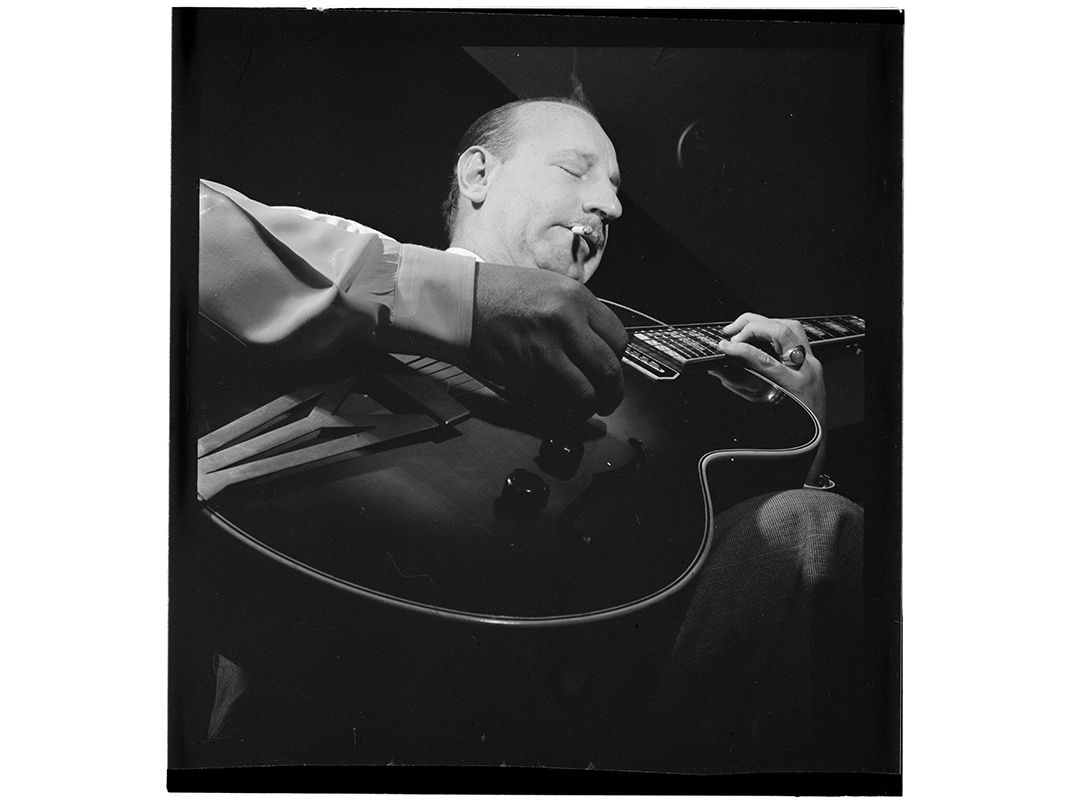

To conclude the album, Schoenberg chose a pair of one-off tunes from lesser-known—but undeniably gifted—artists. Carl Kress’s “Heat Wave” is defined by its warm, summery guitar and the Emilio Caceres Trio’s “China Boy” opens with zany, frenetic violin and stays feisty till the end.

Listeners can expect more diversity and verve out of the Savory albums as yet on the horizon, slated for release over the course of the coming months. The one notable exception with respect to the former category is the next installment, which will feature Count Basie material exclusively—a source of excitement in its own right.

As far as takeaway is concerned, Schoenberg has a simple hope for his listenership: that they—jazz junkies and dabblers alike—will enjoy the music, and will appreciate the fact that it was very nearly lost to history. Indeed, he expects that many will be able to relate personally to the moment of discovery that brought the Savory Collection into existence.

“It’s your grandmother’s scrapbook,” he tells me. “It’s those photographs that some ancient relative took somewhere, and no one knows what it is, but it turns out to be something significant. Or that dusty old folder [that] actually contains something written by somebody that would mean something to someone else.”

After all, as Ken Burns notes in his intro (quoting Whitney Balliett), jazz is the sound of surprise.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)