How Does the Hirshhorn’s 60-Foot “Needle Tower” Stay Upright In A Stiff Wind?

In the 1960s, when artist Kenneth Snelson mingled architectural innovation with abstraction, the result was heavenly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/6a/fb6a2033-502f-4347-bc2f-6242c42146ba/744d2.jpg)

How often do you look up?

That’s what Valerie Fletcher wondered when she first climbed inside Kenneth Snelson’s Needle Tower, a 60-foot sculpture of steel wires on display outside the Hirshhorn Museum, before her 30-plus year career as senior curator there. Towering above her was a seemingly endless procession of six-point stars disappearing into the sky. She suddenly understood what made the sculpture such a departure from anything seen before in art.

“It makes us look up and realize that there’s a cosmos and an infinite up there,” Fletcher says. “To me, that’s very uplifting. Art is too often an object that the viewer stands apart from and looks at.”

The structure was built in 1968, and has been on continuous display since the museum’s namesake Joseph Hirshhorn donated it in 1974. It remains one of the most popular works of art. Needle Tower is so popular, in fact, that Fletcher says it was placed in its central spot outside the museum for a reason: so that when people pass it on their way from the Air and Space Museum, they are drawn to the Hirshhorn.

Those who see Needle Tower often wonder how the 60-foot tower, with barely 14 inches of contact with the ground, stays upright. The structure’s strength comes from a principle developed by Snelson under the guidance of renowned architect and engineer R. Buckminster Fuller, a teacher of Snelson’s at Black Mountain College in North Carolina after the Second World War. The concept, coined “Tensegrity” by Fuller, employs continuous tension and discontinuous compression between interlocking shapes to give a structure unprecedented stability. Tensegrity is a portmanteau word for tension and integrity (Snelson admitted in an interview that he prefers the term "floating compression."). It relies on Newton’s third law of motion: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Snelson earned a patent for tensegrity in 1965, and consistently uses it in his art. Needle Tower’s structural components are two different types of triangles made of steel wires. The result is a kind of lattice, making the structure profoundly stable.

To begin thinking about tension and compression as an architectural principle, all Fuller had to do was look up. “As a sailor I looked spontaneously into the sky for indicated clues,” he wrote in his 1961 paper, Tensegrity. “I found myself saying, ‘It is very interesting to observe that the solar system, which is the most reliable structure that we know of, is so constituted that the earth does not roll around on Mars as would ball bearings…”

Tensegrity made its way into civil engineering, most notably on geodesic domes. But as Snelson said in an interview, its origins are simple, natural and everywhere: spider webs, bicycle tires and kites held together by crossbeams.

For the most part, Needle Tower is self-sustaining and requires no maintenance. For the first few years the sculpture was on display, nothing had to be fixed, even through intense storms. Over time, the small wires holding the triangles together began to fray and snap when exposed to heavy wind. In the first few decades, the museum replaced only individual elements. Eventually, they had Snelson replace the top portion. In 2010, around the time of the replacement, the museum’s staff began to lay Needle Tower down on its side whenever there was a forecast for near hurricane winds.

Very few people can repair and maintain pieces as complex as Snelson’s. Part of the reasoning behind having him replace the top portion was to see how he did it, so it could be replicated in years to come.

Needle Tower, and the architectural innovation behind it, emerged during the Post-War era when the United States led the world in technological innovation. But the art world followed suit slowly, only beginning to delve into three-dimensional geometry by the late 1960s.

“Needle Tower brings together advanced engineering methods with a very sophisticated aesthetic of abstraction,” Fletcher says. “Abstraction usually isn’t something the general public warms up to, but this piece is one of their all-time favorites.”

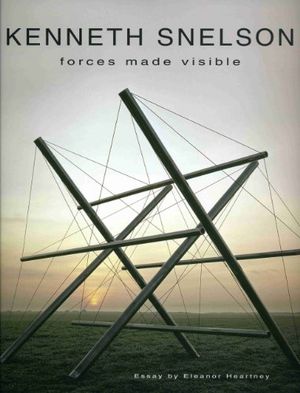

Kenneth Snelson: Forces Made Visible

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Ben_Yeager.jpg)