How Frida Kahlo’s Love Letter Shaped Romance for Punk Poet Patti Smith

Sealed with a kiss, the 1940 note reflects the “earthly human love” between Kahlo and fellow artist Diego Rivera

My mother, a waitress, was very diligent about figuring out what I was into, so that she could buy me the right books. For my 16th birthday she found The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera, this huge and very famous biography.

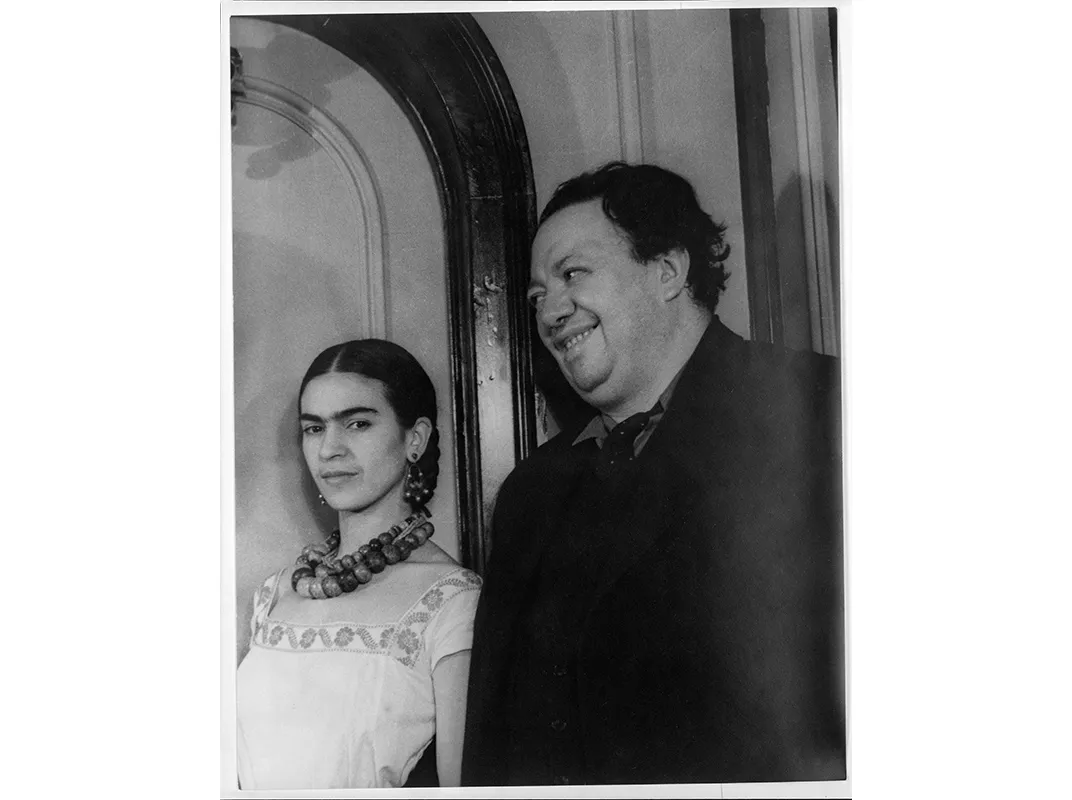

I had already decided to be an artist, and I also dreamed of meeting another artist and being supportive of each other’s work. This book was perfect. All of the relationships Diego Rivera had were so interesting, but Frida Kahlo was by far the most compelling and enduring one. I loved her. I was taken by her beauty, her suffering, her work. As a tall girl with black braids, she gave me a new way to braid my hair. Sometimes I wore a straw hat, like Diego Rivera.

In certain ways, they were a model for me, and they helped me really prepare for my life with Robert (Mapplethorpe, the late photographer and Smith’s longtime collaborator). These were two artists who believed in one another, and each trusted the other as a shepherd of their art. And that was worth fighting for through their love affairs and fights and disappointments and arguments. They always came back to each other through work. They were lost without each other. Robert used to say any piece of work he did didn’t feel complete until I looked at it. Diego couldn’t wait to show Frida the progress of his murals, and she showed him her notebooks. The last painting Frida painted in her life was watermelons, and at the end of his life, Diego also painted watermelons. I always thought that was beautiful: this green fruit that opens up, the pulp, the flesh, the blood, these black seeds.

One dreams that we could meet these people that we so admire, to see them in their lifetimes. I’ve always had that drive. Why do people go to Assisi, where St. Francis sang to the birds and they sang to him? Why do people go to Jerusalem, to Mecca? It doesn’t have to be religion-based. I’ve seen Emily Dickinson’s dress and Emily Bronte’s tea cups. I went to find the house where my father was born. I have my son’s baby shirt because he wore it. It’s not more or less precious to me than St. Francis’ slippers.

In 2012, I traveled to Casa Azul in Mexico City, the house where they led their life together. I saw the streets where they walked and the parks where they sat. I sipped watermelon juice from a street vendor’s paper cup. Casa Azul, now a museum, was so open. One could see their artifacts, where they slept, where they worked. I saw Frida’s crutches and medicine bottles and the butterflies mounted above her bed, so she had something beautiful to view after she lost her leg. I touched her dresses, her leather corsets. I saw Diego’s old overalls and suspenders and just felt their presence. I had a migraine, and the director of the museum had me sleep in Diego’s room, adjacent to Frida’s. It was so humble, just a modest wooden bed with a white coverlet. It restored me, calmed me down. A song came to me as I lay there, about the butterflies above Frida’s bed. Shortly after waking, I sang it in the garden before 200 guests.

I don’t mean to romanticize everything. I don’t look at these two as models of behavior. Now as an adult, I understand both their great strengths and their weaknesses. Frida was never able to have children. When you have a baby you have to relinquish your self-centeredness, but they were able to act like spoiled children with each other their whole lives. Had they had children their course would have altered.

The most important lesson, though, isn’t their indiscretions and love affairs but their devotion. Their identities were magnified by the other. They went through their ups and downs, parted, came back together, to the end of their lives. That’s what I sensed even at 16. That’s what Robert and I experienced that never diminished.

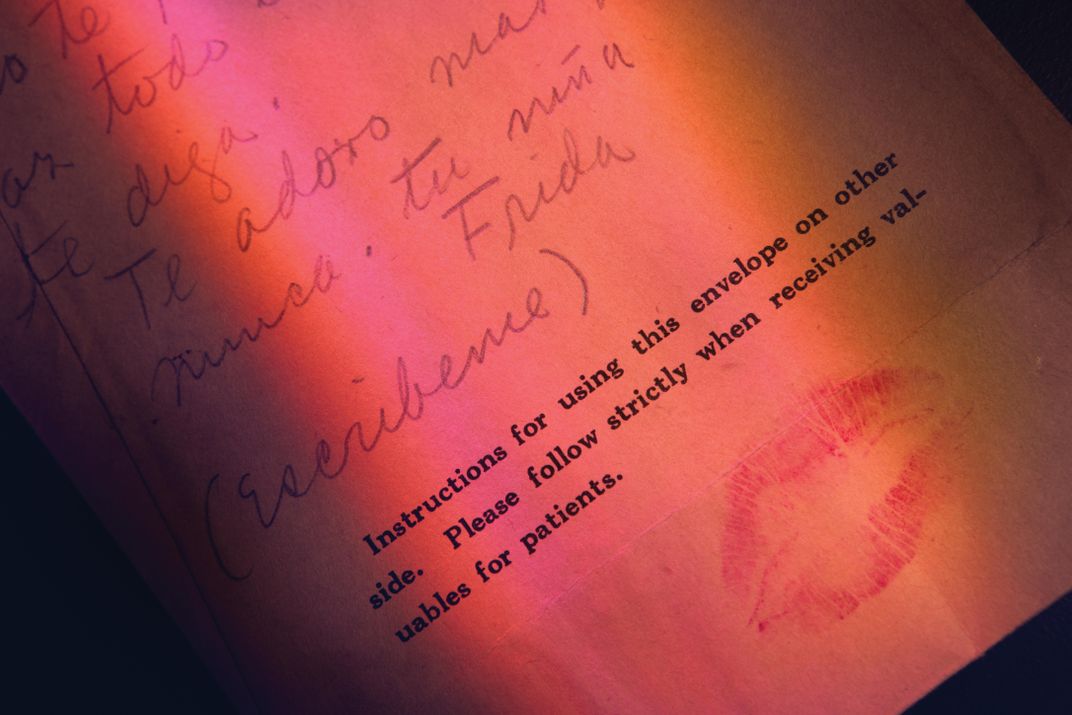

This letter from Frida to Diego— scrawled on an envelope she had once used to store valuables during a hospital stay, written in 1940 as Frida departed San Francisco, and now in the collections of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art—is a testament to why they lasted. They didn’t have a passionate relationship that dissipated and was gone. They had an earthly human love as well as the loftiness of a revolutionary agenda and their work. The fact that this isn’t a profound letter makes it in some ways more special. She addressed it to “Diego, my love”—even though this is the most mundane, simplest correspondence, she still noted their love, their intimacy. She held the letter in her hands, she kissed it with her lips, he received it and held it in his hands. This little piece of paper holds their simplicity and their intimacy, the earthiness of their life. It contains the sender and the receiver.

As artists, every scrap of paper is meaningful. This is brown, folded. He saved it. Somebody kept it. It still exists.

* * *

Related Reads

The Letters of Frida Kahlo