How a German Archaeologist Rediscovered in Iran the Tomb of Cyrus

Lost for centuries, the royal capital of the Achaemenid Empire was finally confirmed by Ernst Herzfeld

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/04/35042f04-5617-4407-acc2-16dc8de9ce83/fsaa604gn1543c1024x791web.jpg)

Alexander the Great rode into the city of Pasargadae with his most elite cavalry in their bronze, muscle-sculpted body armor, carrying long spears. Some of his infantry and archers followed. The small city, in what is today Iran, was lush and green. Alexander had recently conquered India. Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor and parts of Egypt were all part of his new empire. The people of Pasargadae likely expected the worst—when the world's most dangerous cavalry shows up on your street, you are probably going to have a bad day. But he hadn't come to fight (the city was already his).

The world's most powerful ruler had come to pay tribute to someone else.

The young conqueror was looking for a tomb containing the remains of Cyrus the Great. But it had recently been ransacked (probably for political reasons). Alexander the Great was furious. An investigation was launched, trials were held.

Alexander ordered the tomb's contents replaced and restored. According to one Greek historian, this included “a great divan with feet of hammered gold, spread with covers of some thick, brightly colored material, with a Babylonian rug on top. Tunics and a Median jacket of Babylonian workmanship were laid out on the divan, and Median trousers, various robes dyed in amethyst, purple, and many other colors, necklaces, scimitars, and inlaid earrings of gold and precious stones. A table stood by it, and in the middle of it lay the coffin which held Cyrus' body.”

Cyrus had been dead for about two hundred years. Alexander idolized him. In the year 559 BCE, Cyrus ordered the construction of Pasargadae.

This city became the first capital of the Achaemenid empire that Cyrus built. “It was the super power of its day,” says Massumeh Farhad, chief curator of the Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Galleries of Art. “This is the first super power ever. It was Cyrus who captured Babylon. His empire reached from what is now Afghanistan, included much of Egypt and went as far as the Mediterranean.”

Cyrus' Persian-dominated empire would come to serve as both inspiration and eventual rival to Alexander. Cyrus created a template for not only military conquest but also the political infrastructure to manage and maintain an empire. A postal system, roads, taxation and irrigation systems; all begun years before the Roman Republic even existed.

Pasargadae was the capital of an empire known as well for its mercy and relatively liberal government as for its ability to invade and dominate. Cyrus made a point of allowing freedom of religion, language and culture within his empire.

Both the Christian and Jewish bibles laud him for issuing the Edict of Restoration. After years during which many Jews were kept as captives in Babylon, Cyrus captured Babylon, gave them their freedom and allowed them to return home. For this act, he is the only non-Jew in Jewish scripture who is referred to as 'messiah' or 'His anointed one' (Cyrus is presumed by many scholars to have been a Zoroastrian but it isn't clear that he followed any particular religion).

Yet somehow, both the city and the tomb were essentially misplaced. The buildings and gardens fell into disrepair and crumbled. The mausoleum remained standing but locals eventually became confused about who was buried in it. “The tomb was known as that of the mother of Solomon,” says Farhad.

“It's one of the most iconic buildings of the ancient world. But its function was forgotten.”

By the early 20th century, nobody was sure exactly where Cyrus had been buried and it wasn't clear where the former capital of his empire was.

Thousands of years after Alexander paid his respects, Pasargadae was visited by another foreign adventurer looking for the same tomb as Alexander.

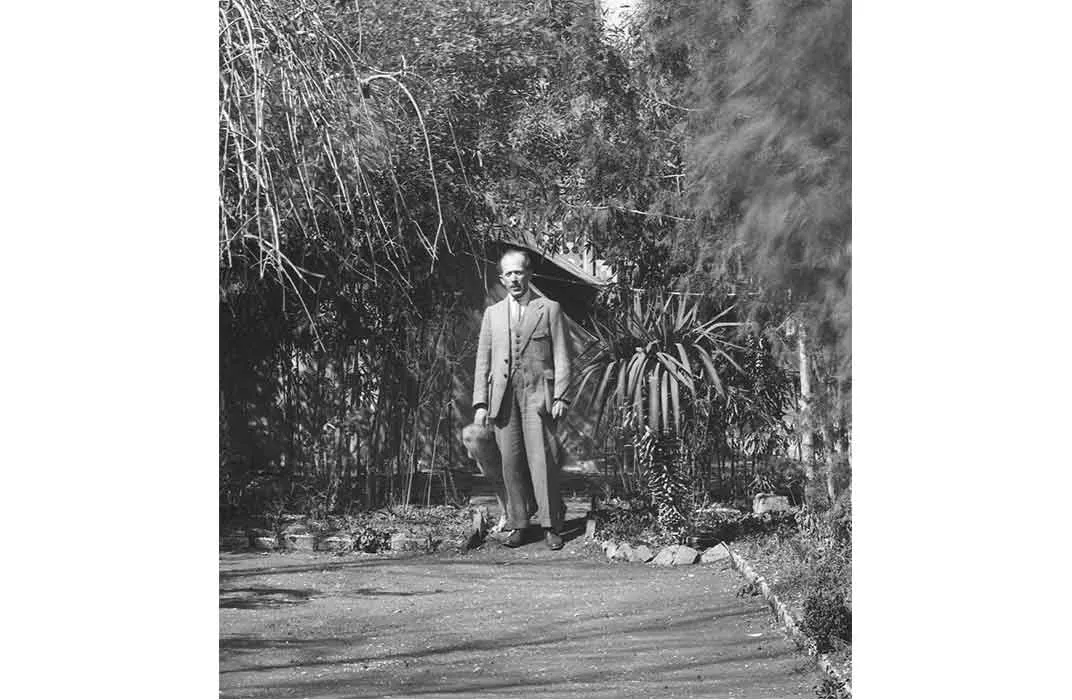

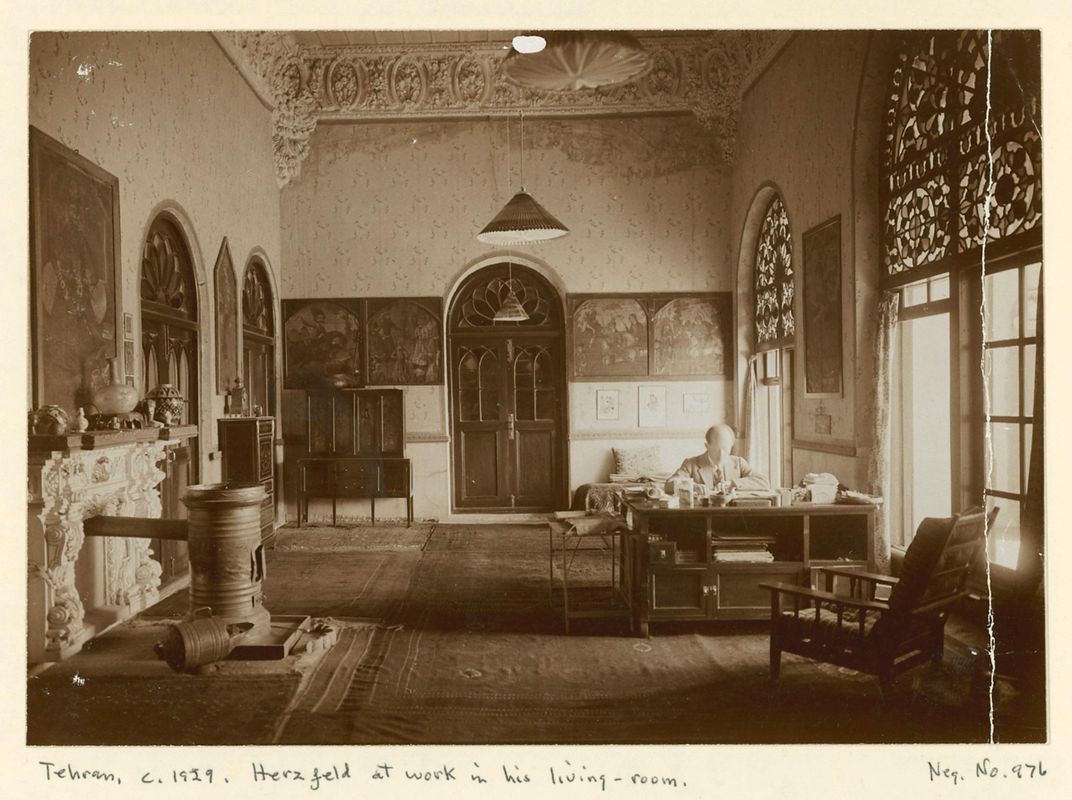

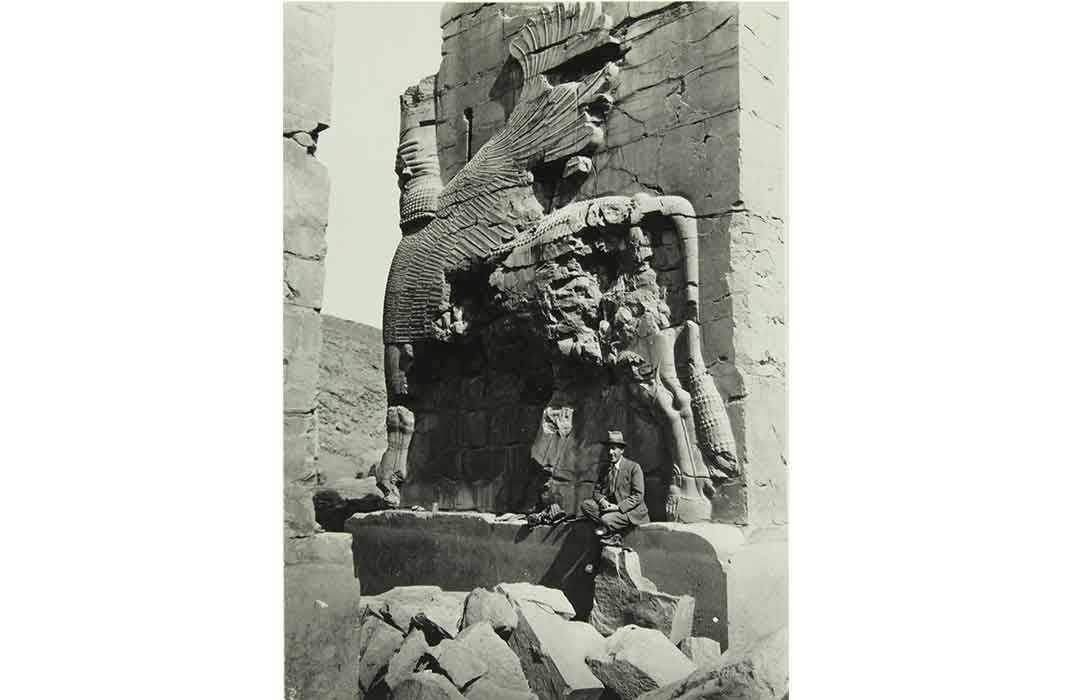

This time it was a German rather than a Macedonian. Ernst Herzfeld arrived in 1928 to begin mapping and photographing the city. He was the world's first professor of middle east archeaology. Herzfeld determined that the tomb was that of Cyrus, who had become a historical icon and a part of Iran's national identity.

Modern archeology was still a new replacement for the haphazard looting that had passed for exploration before. Herzfeld was meticulous, scientific and careful. He soon produced maps of the site that showed how Pasargadae had been more than just an administrative capital. It was a miracle of design. Herzfeld's journals, photographs and other materials are now found in the collections of Smithsonian's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, where an exhibition of his drawings, notes and photographs is now on view.

“It was an effort to create a palace city with gardens,” says Farhad. “The gardens play a critical role. The buildings were built around these gardens. There were pavilions... But they had integrated the landscape into the architecture, which was a novel and new idea. That's why the plans for Pasargadae are so important. It was a type of palace that didn't exist before.”

“He was right in the middle of empire building,” says David Hogge, head of the Freer and Sackler Archives. “But the architecture that is there very much indicates the international character of the empire; Persian, Greek and even Egyptian elements in the architecture.”

Pasargadae was never a huge city, even by the standards of the time it was founded. But it was Cyrus' personal vision and probably a very pleasant place to visit. “There was a complex system of irrigation canals which Herzfeld discovered,” Hogge says. “It really was very novel when it was built.” The gardens may have contained almond, pomegranate and cherry trees. Clover, roses and poppies probably flowered. It would have been a fragrant place (the Persians also happened to be the first people known to use perfume).

Herzfeld methodically probed for the outlines of foundations and canals. He sketched reconstructions of shattered statues. And in his drawings and maps he brought Cyrus' city back to life for us, just a little bit. “He really made the foundation,” says Farhad. “You cannot do any research on the ancient world without going back to his work. He's not as well known as he should be.”

After Cyrus' death in 530 BCE, the empire's capital was moved to the nearby city of Persepolis (which was also probably founded by Cyrus). Some of the buildings that were still under construction at the time of his passing were never completed. The region gradually became less politically important. “What happened, clearly it was no longer the center of the empire,” says Farhad, “and then with the coming of Islam, the center of importance sort of shifted. . . Persepolis and Pasargadae represented the pre-Islamic period.”

In spite of his pre-war international archeological expeditions, Herzfeld was no Indiana Jones. He was known for being dry, down-to-Earth and serious (although he did travel to Iran with a pet boar named Bulbul). He was also Jewish. In 1935 he lost his support from the German government. The rise of the Nazi party forced him to seek employment and backing elsewhere. Ironically, the Jewish man who discovered the tomb of the emperor responsible for the Edict of Restoration was himself forced away from his home because of his religion.

Herzfeld ended up in the United States teaching at Princeton at the same time as Albert Einstein. He died in Switzerland in 1948 at the age of 68. Cyrus may have lived to be as old as 70 (his exact birth date is unclear) and is thought to have died in battle.

By the time Herzfeld found his tomb, it had been looted again and Cyrus' bones were gone.

Alexander's empire exceeded that of his hero but he died of a sudden illness believed by some to be the result of poisoning. He was only 32. Modern archaeologists are still searching for his tomb.

“Heart of an Empire: Herzfeld’s Discovery of Pasargadae” is on view at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. through July 31, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)