How the Gold Rush Led to Real Riches in Bird Poop

The ships carrying gold miners to California found a way to strike it rich on the way back with their holds full of guano

:focal(531x158:532x159)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/f3/9ff39117-2db9-409b-a8b9-332d0b13bc71/bk007555web.jpg)

The California gold rush began when San Francisco businessman Samuel Brannan found out about a secret discovery, set up a store selling prospecting supplies, and famously marched through the streets in 1848 shouting, “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

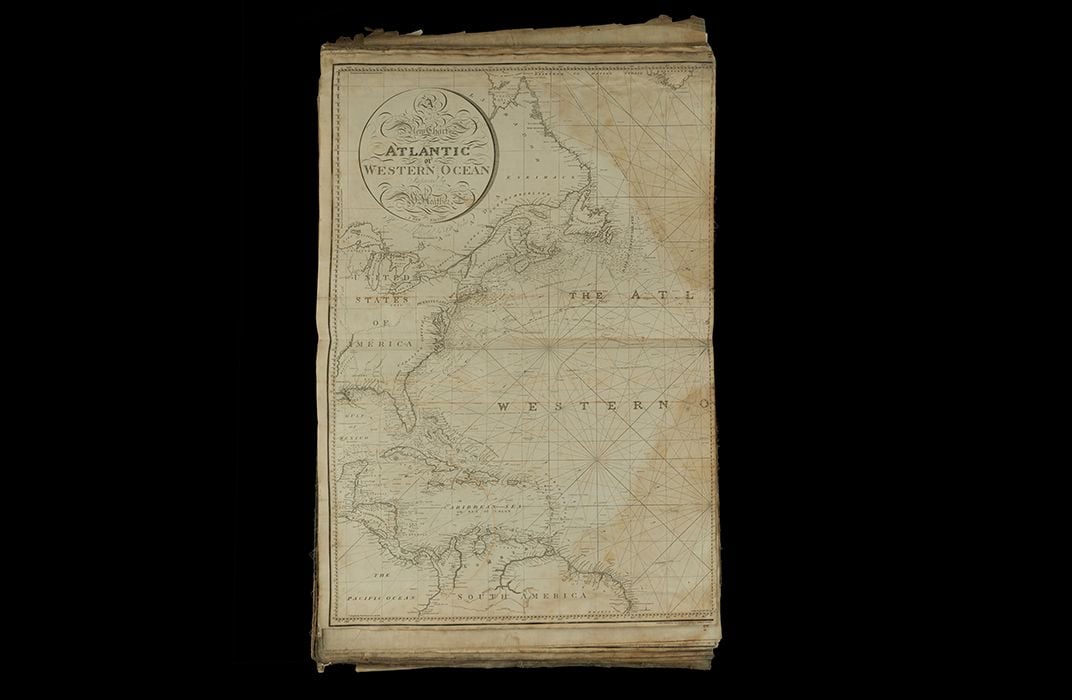

People from all over the young United States rushed to the west coast. Some traveled over land but many made the trip on clipper ships that sailed around the tip of South America. The long way around, back in the days before either the Suez or Panama canals existed.

Few people today are aware of what those ships did on their way back.

Ship owners didn't want their vessels returning with empty holds so they looked for something to transport back east that they could sell. What they found was guano, or the accumulated droppings of nesting sea birds (and sometimes bats) that had built up over thousands of years on islands along the route home.

Nobody ran through the streets yelling “Poop! Poop! Poop from the Pacific Ocean!” It wasn't a glamorous product, but it was free for the taking and had a ready market as fertilizer for America's growing agricultural business.

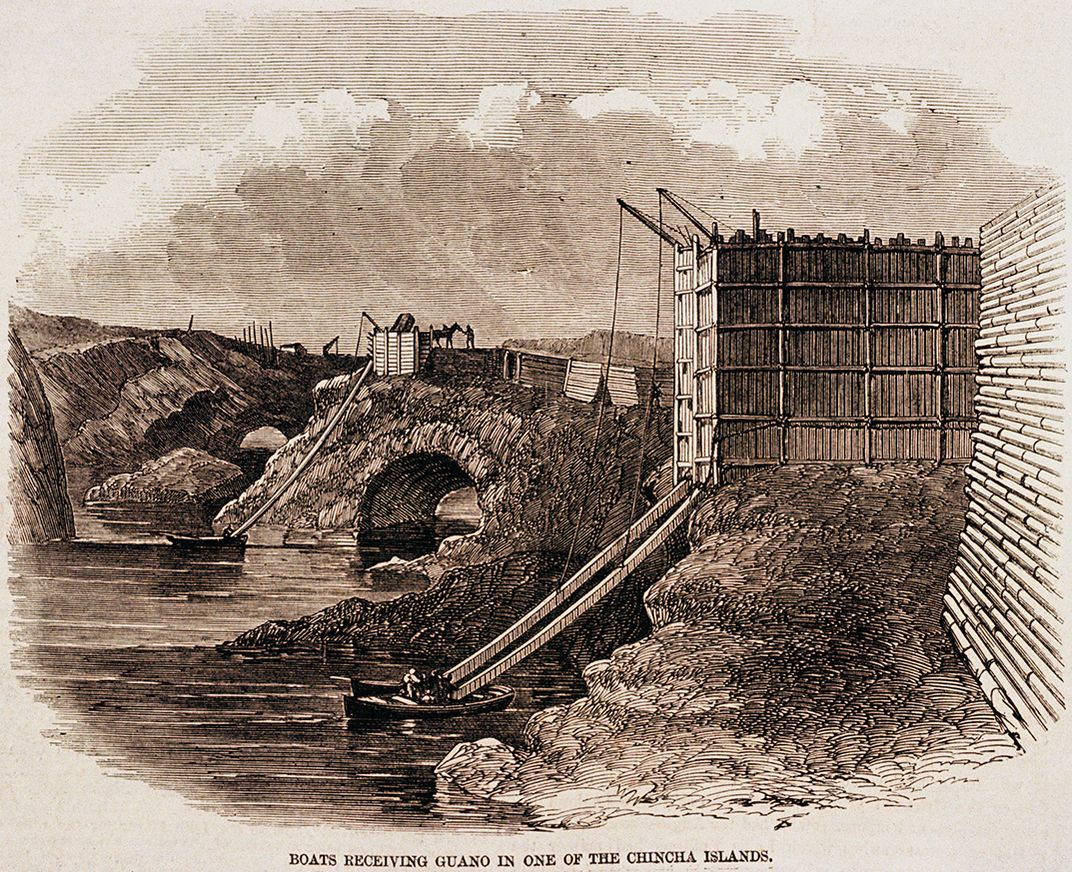

“It was an unbelievable fertilizer because of all the nitrates in it,” says Paul Johnston, curator of the exhibition, “The Norie Atlas and The Guano Trade,” which recently opened at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. “The Chincha islands, birds have been [pooping] on these islands for millennia. It was two hundred feet deep in some places.”

A bona fide guano rush began. But with many of the tiny guano-covered islands located in places where no governments had claimed authority over them, there were concerns about the legal framework for mining the guano.

This prompted the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which allowed United States citizens to claim any unoccupied island or rock that was not under the jurisdiction of any other government. Those islands would then become U.S. territory and American federal laws would apply there.

“We claimed almost a hundred islands or island groups in an effort to extend the richness of the fertilizer,” says Johnston, “and that is basically the start of American imperialism.” Some of those guano islands (long since depleted of their guano) still remain U.S, territories. Midway Atoll, a strategic key to America's defeat of Japan in the Second World War, is among them.

A guano trade existed prior to the California gold rush, but war between Spain and her former colonies followed by political instability had prevented it from flourishing. The gold rush turned a fledgling (pun intended) business into a boom and entwined the trade with the future of the United States.

The historical importance of the guano business, which changed the world economically, environmentally and politically, dawned on Johnston as he supervised the restoration of an old atlas that arrived in his mailbox unexpectedly and without a return address.

“In 2011 I got a call from the library at the Coast Guard Academy in New London,” Johnston recalls, “about an old book of charts that they didn't have any use for any more. I said yeah I'd like to know more about it. And then I forgot about it. About a year later this giant package appeared in my mail with no return address.”

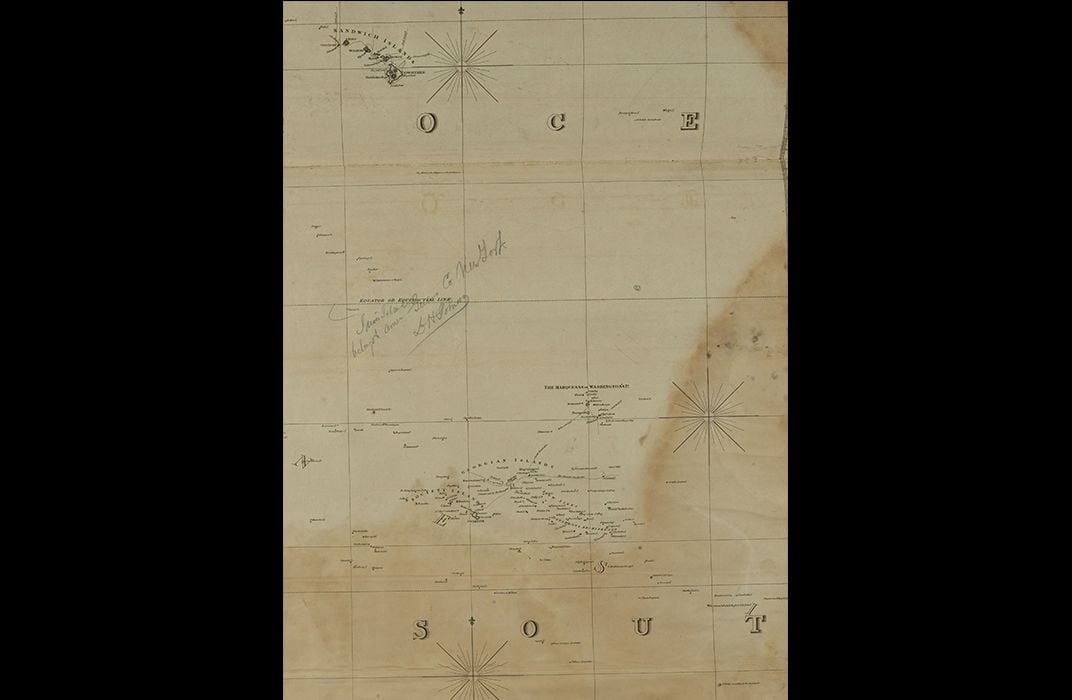

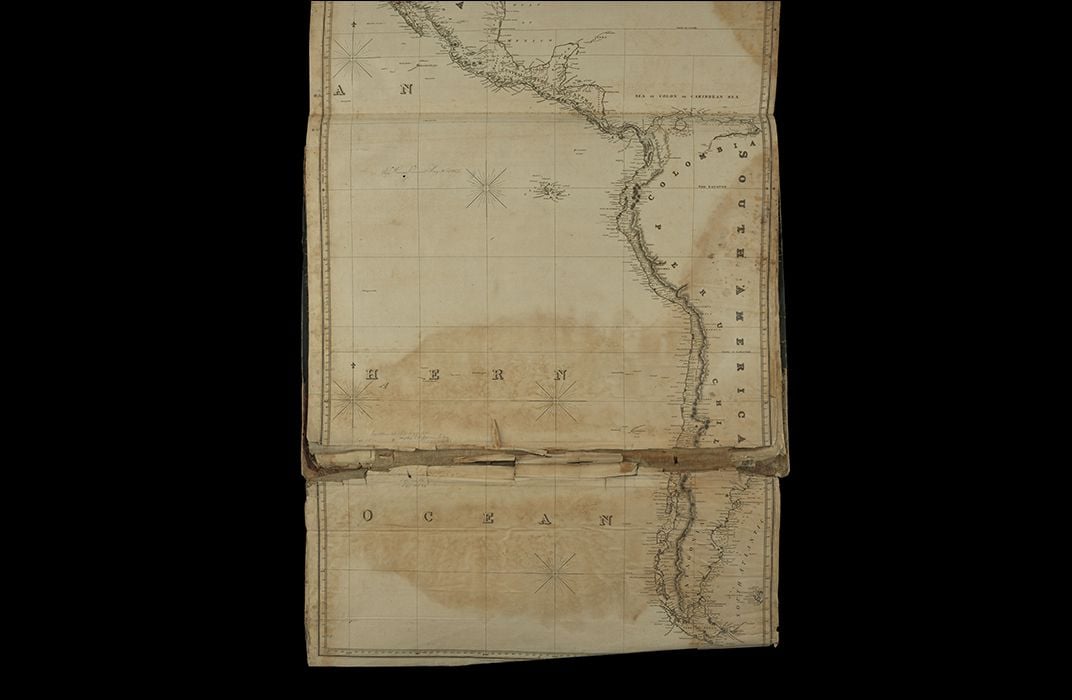

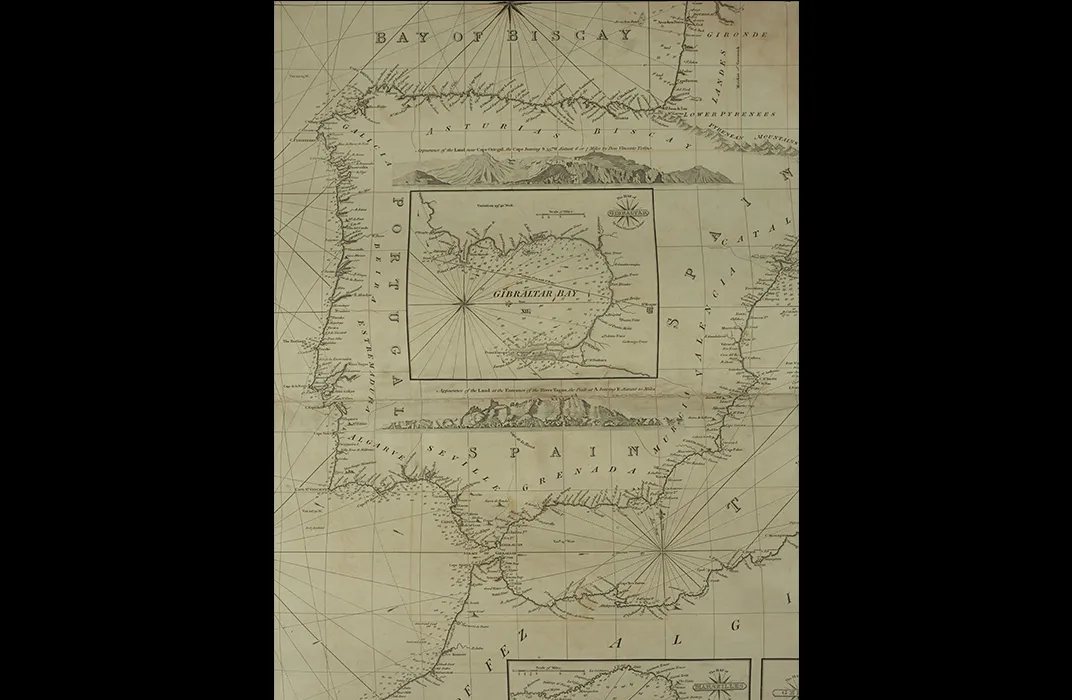

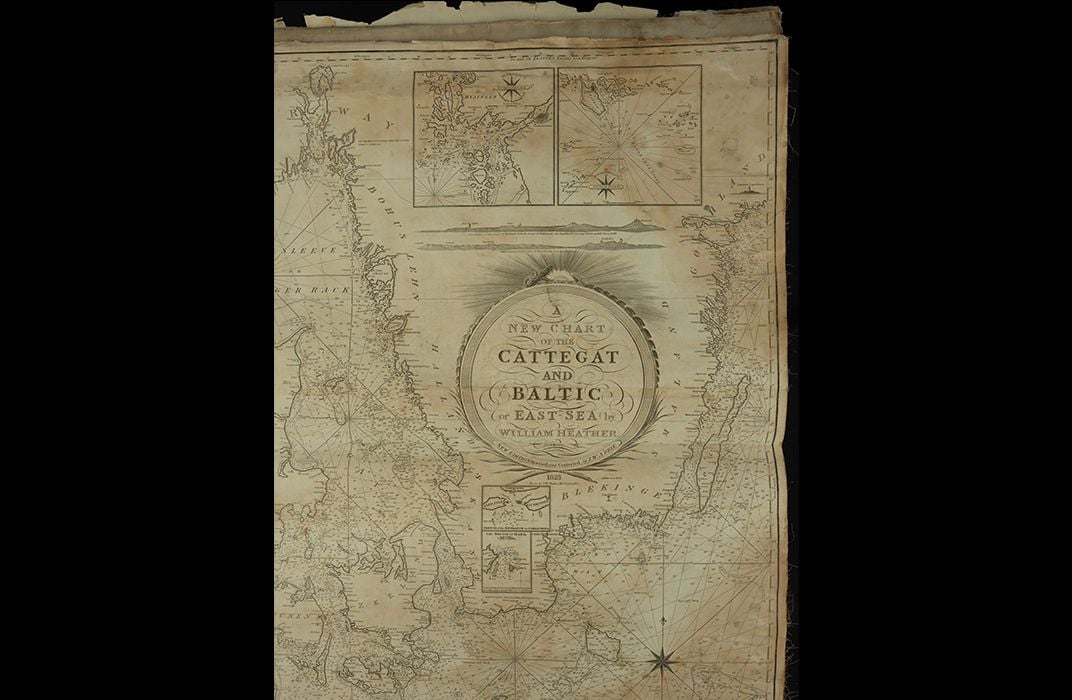

The atlas, entitled The Marine Atlas, or a Seaman’s Complete Pilot for all the Principal Places in the Known World, turned out to have been produced by John Norie, an important English mapmaker in the mid-19th century. At the time, the entire world hadn't quite been charted.

New shoals were still being discovered and archipelagos of islands that had been far-flung and economically unimportant weren't mapped. As the economy changed, obscure fly-speck islands covered in poop suddenly became very important to chart. Norie constantly updated his charts to reflect new discoveries and measurements. A captain sailing a clipper ship through a network of coral reefs without the latest charts was risking his ship, his crew and his life. Norie's charts were among the best of his time and his customers included the East India Company and the British Admiralty.

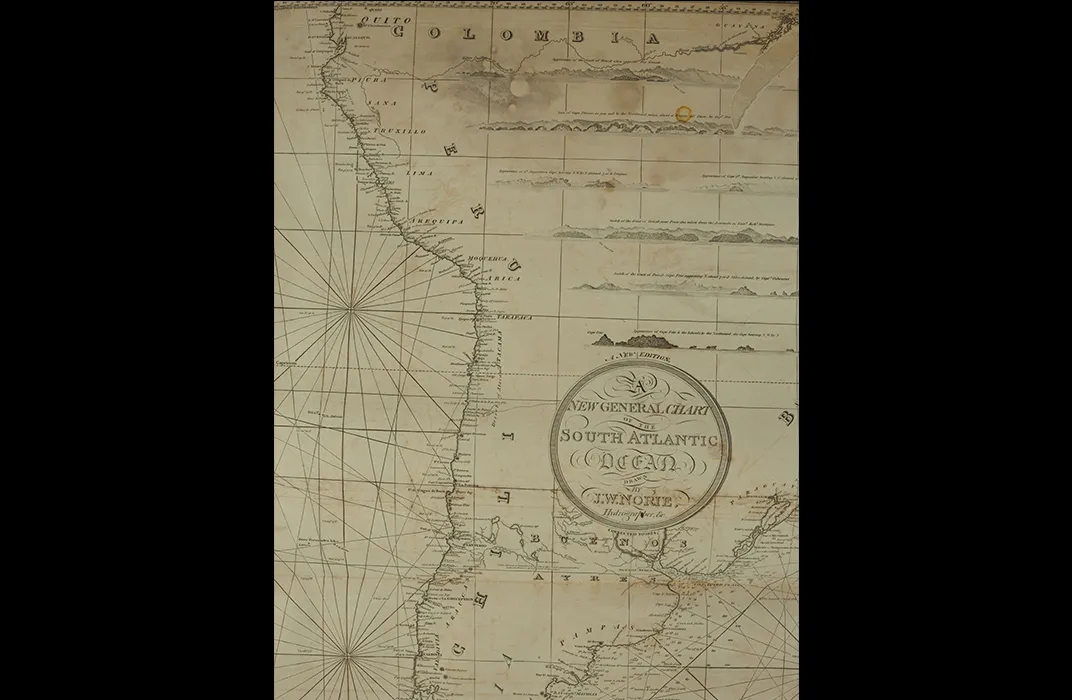

Norie's charts of the coast of South America were important in part because past charts had been deliberately poor. “As long as the information isn't exact, where the latitude and longitude of a particular river or border is, you could fudge things about where the boundaries were and who owned what,” says Gregory Cushman, a history professor at the University of Kansas and the author of the book, Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World.

“Being inexact was to the political advantage of the people fighting over boundaries. There was a lot of pressure to be vague or even to intentionally deceive. Good maps weren't in the best interest of the Spanish, the Portuguese,” says Cushman. “And the British, because they didn't own territory in these places and they were just traders, secrecy got in the way of their interests. So they had an interest in clear mapping because they were late coming to the Pacific.”

The atlas, held by Smithsonian's Dibner Library for the History of Science and Technology, is of the 7th edition and is the only surviving copy known to exist.

Janice Ellis, one of the conservators involved in restoring the atlas, noticed some subtle clues about its age.

“As I recall, the first clue to the binding’s date was the watermark on the endleaves,” says Ellis, “which would have been added to the printed pages when they were bound. The watermark reads 'Fellows 1856...' Interestingly enough this is the same oversized Whatman Turkey Hill paper used by other artists and engravers, like JMW Turner and James Audubon.”

As restoration of the book began, volunteers and staff were struck by its beauty. “People started coming up to my office and saying that there's this really beautiful old book and you ought to do something with that,” Johnston says. “At the time, to me it was just a bound volume of old charts, but to other people who are intrigued by the actual beauty of the chart maker's craft, they saw that it was special. Some of them are the most beautiful I've ever seen. That's when I discovered the notations off the coast of Chile where the guano trade was going on.”

An unknown mariner was making his own notes by hand on the pages of the atlas that include important guano producing regions. Johnston began researching what a ship would likely have been doing off the coast of Chile in the 1860's. As he dug deeper, he found that the atlas and the guano trade has a coincidental tie to the early history of the Smithsonian Institution.

The federal government became involved in the guano trade very quickly. One of the provisions of the Guano Islands Act empowered the President to direct the Navy to protect claims to guano islands. Now interested in the stuff, the Navy looked for someone to analyze the guano to see what its qualities really were. The man they found for the job was Joseph Henry; chemist, inventor of the electric relay, and the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Henry analyzed 17 samples of Pacific guano for the Navy and developed a report describing their various qualities as fertilizer.

“The reason it turned into a big industry was science,” says Cushman.“The identification of ammonia and phosphates as something that can be used for fertilizer was an important thing in the 19th century... science allowed people to realize how valuable guano was for agriculture.”

The prospect of massive wealth on an unseen rock in another hemisphere made the guano business ripe for fraud. “There was sort of a shell game going on," says Johnston. “A lot of the islands were jagged, just shooting up in the air. They didn't have natural harbors so they had to anchor offshore.” Physically getting at the guano and loading it on to ships could be expensive, awkward, and in some cases entirely impractical. “Because of the difficulties of extraction and keeping your claim, these companies would come back to the east coast, they'd sell shares and sell the company to some sucker,” he says.

But once it was brought to market and applied to crops, the stuff really worked. “Among cotton planters in the South, guano was a prestige commodity,” says Cushman. “By using guano you were, as a plantation owner, showing your neighbors that you were a modern farmer, a scientific farmer, and had the economic means to pay for this expensive bird crap from the other side of the world.”

Like California's gold nuggets, the guano wasn't going to last forever. Constant digging scared away the seabirds that had been nesting or resting on the rocks. No more guano was being produced. Populations of sea birds crashed. Recovery was hampered by the fact that fishermen had come in along the same routes being used by the guano traders and were netting the sardines that the birds had previously been eating and converting to guano.

By the early 20th century most of the guano islands had been exhausted. Now hooked on fertilizer, industry turned first to using fish for its manufacture and later to making synthetic fertilizer. Many of the steeper rock spires are once again unoccupied and in many cases ended up being claimed by other nations. But a few of the islands remained settled. America had used poop as its motive to expand into an empire stretching across the Pacific. Today, those Pacific islands are more important than ever before due to the exclusive economic zones that extend for two hundred miles off of any country's coastline under international law.

Any oil and natural gas that lie under the sea floor in those areas are the exclusive property of the United States. Extracting those resources was unimaginable when the islands were first claimed.

Perhaps the guano and oil are more valuable than the gold rush that started the whole thing. Guano and oil aren't pretty but they are a lot more useful to people than a shiny bar of metal. All that is gold does not glitter—especially when it's ancient bird poop.

"The Norie Atlas and the Guano Trade" is on view through January 4, 2017 in the Albert Small Documents Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)