How Disney’s 1942 Film Bambi Came to Be Influenced by the Lush Landscapes of the Sung Dynasty

Chinese-American Artist Tyrus Wong’s Brush With Destiny

Pamela Tom, a documentary filmmaker, says she is still thankful for the chance encounter 14 years ago that led her to the now 103-year-old Chinese American artist Tyrus Wong.

She first heard his name in a short film included with the Disney home video Bambi that Tom watched with her young daughter about the making of the 1942 classic. Wong wasn’t interviewed in the film, but the other animators spoke of his work with such admiration that Tom knew she had to find and tell the artist’s story. She successfully tracked him down in 1998, locating the playful Wong in Los Angeles trying to teach goldfish in his pond to eat at the sound of a bell, and building kites and flying them off the Santa Monica pier.

Tom’s mission to make Wong’s story as familiar as the beloved children’s film that he helped to create, is at the core of her new documentary, American Masters: Tyrus, airing Friday, September 8, 2017 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) and honoring the 75th anniversary of the Disney film Bambi.

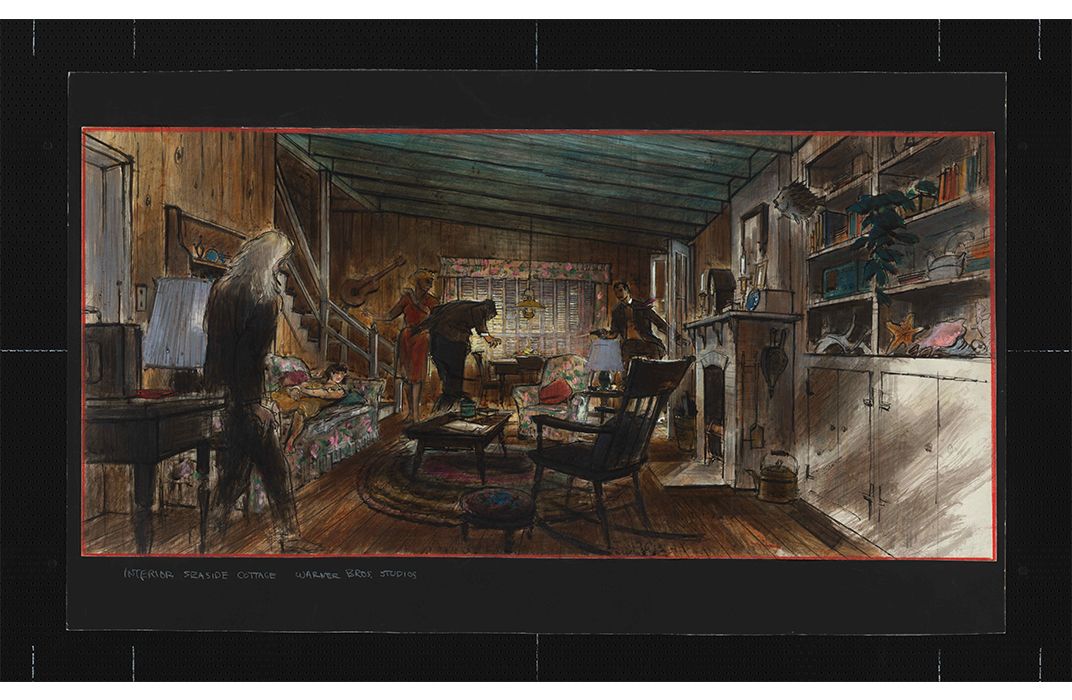

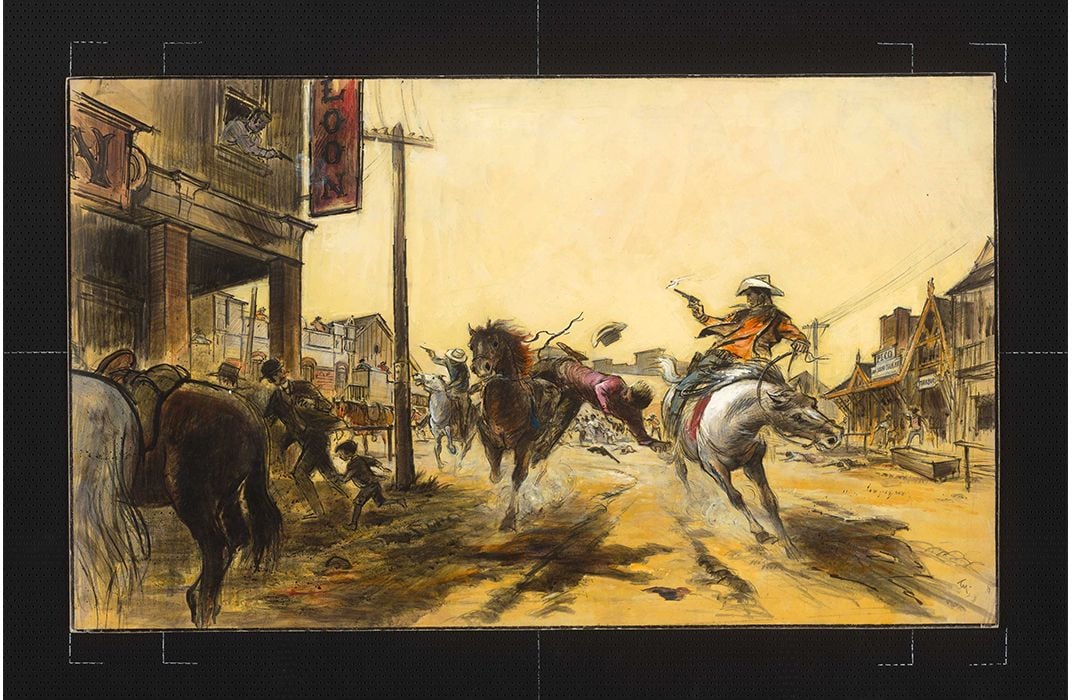

While Wong’s culturally-infused art, is largely unknown to the American general public, his Hollywood career spanned more than 30 years and his illustrations appeared in such iconic American films as Rebel without a Cause, Harpers, The Wild Bunch, and PT 109.

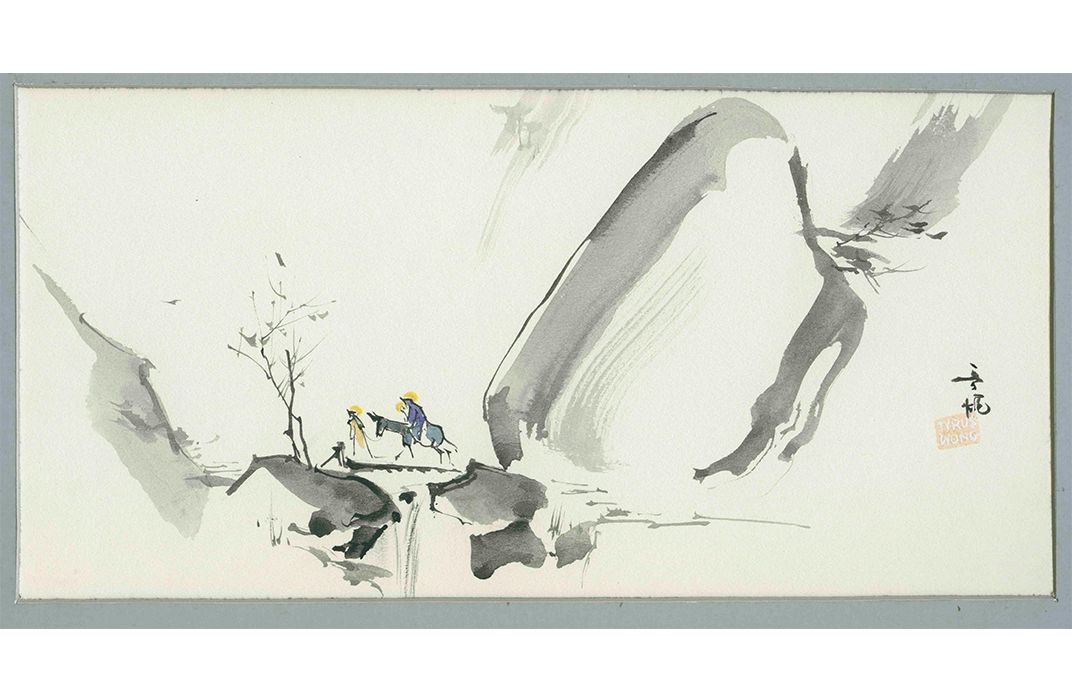

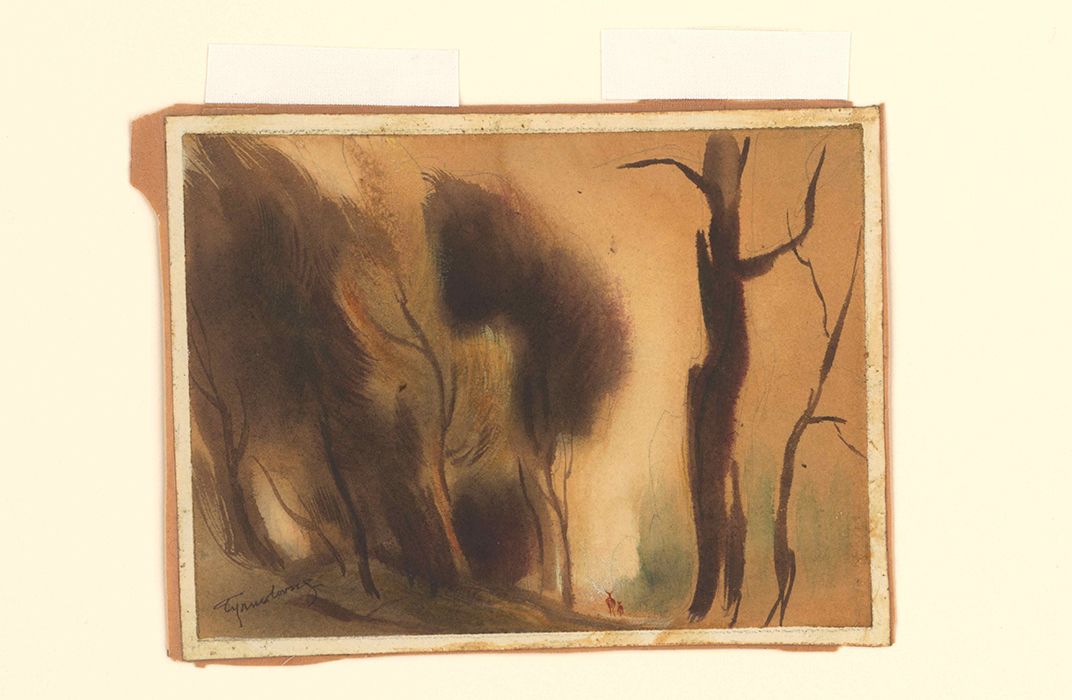

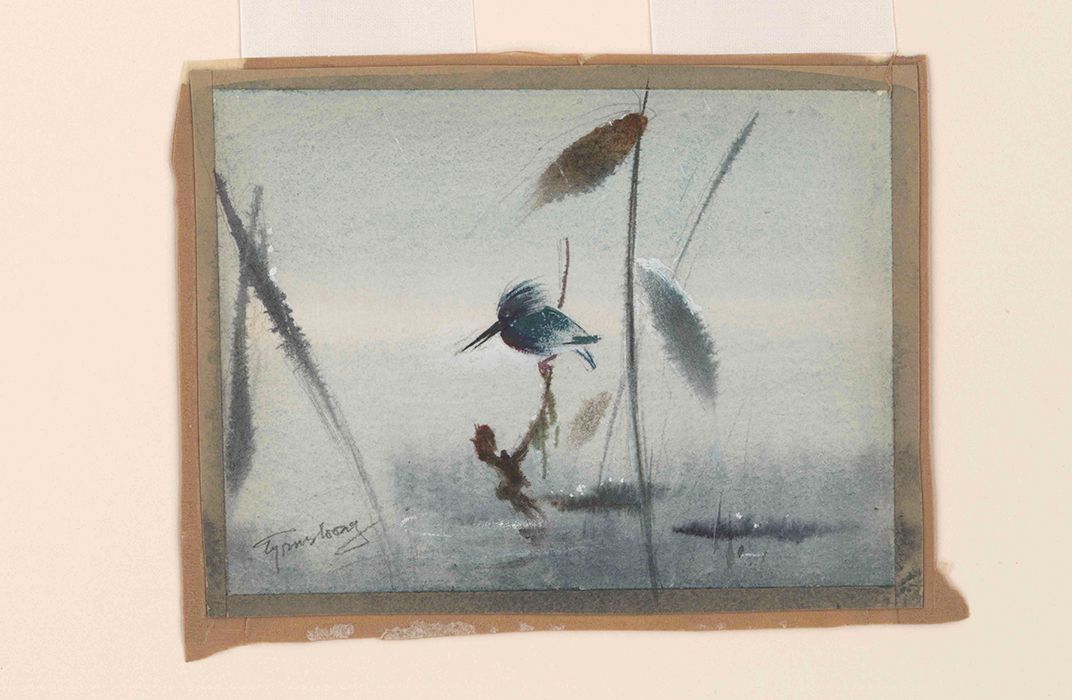

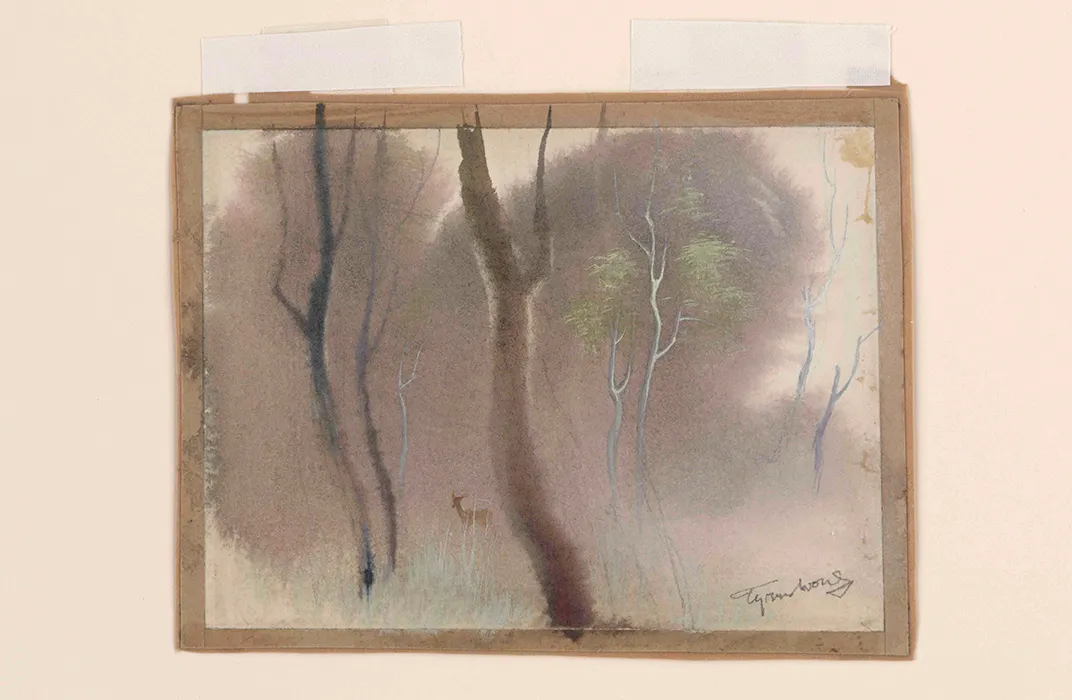

He got the job on the Bambi project by taking a bit of a gamble. He was a young artist employed by the Disney studio, but tasked with the entry-level job of finishing off the work of the animators and crafting the “in-between” animations that completed the characters’ movements. Wong had learned that studio executives were creating a film from the new novel, Bambi, A Life in the Woods by Felix Salten. Tom says the young artist read the book and without consulting his supervisor, “took the script and painted some visual concepts to set the mood, color and the design.” His sketches recalled the lush mountain and forest scenes of Sung dynasty landscape paintings. His initiative paid off. Walt Disney, who was looking for something new for the film, was captivated and personally directed that Wong be promoted. Today, top animators and illustrators revere Wong’s work. Children today are as enchanted by the misty, lyrical brushstrokes of Wong’s colorful nature scenes, inspired by his training at Otis College of Art and self-study of Sung Dynasty art and the Chinese alphabet, as they were in 1942. His work has been much admired in a retrospective on view in San Francisco at the Walt Disney Family Museum (Hurry in, the show closes February 2, 2014).

“Look at his Bambi illustrations, they look like Chinese paintings,” says Tom. “He wasn’t trying to be clever, just himself. What I found remarkable was that he was retaining his Chinese influence.” And at a time, she adds, when it was difficult for immigrants to retain their heritage and be accepted as American.

“Now you see a lot of inclusion and diversity in life. For him it could have been a hindrance but it wasn’t. He worked in film and fine art. He designed Christmas cards, and painted calligraphy on ceramics that were sold in high end department stores. His work is almost like Chinese-American art that he interpreted, made his, and [made] accessible to everyone else.

“One of the people in my film says what made his (Wong’s) work so successful was that it was clearly from another country, but it was accessible and appealing to everyone,” she adds.

Born in 1910 Canton, today's Guangshou, China, Tyrus Wong was nine-years old when he immigrated to California to be with his father, who had arrived several years earlier. However, the young boy was detained for an entire month at Angel Island, awaiting papers and offering him a glimpse of what lie ahead in his new homeland.

Wong’s Chinese-American world was dominated by men, laborers in jobs no one else would take, and separated from their wives, daughters and children who couldn’t immigrate because of strict exclusionary immigration practices targeting the Chinese. After coming to America, Wong would never see his mother again.

Home for Wong and his father was a Sacramento boarding house connected to a brothel. When his father lost money in a failed business deal he went to Los Angeles to work in a Chinese gambling hall, leaving his son behind with family friends until the two could be reunited. His father always supported Wong’s artistic dreams, even borrowing money to support the art training at Otis College, where Wong was the youngest student.

“He’s funny. He’s likable. Complex, modest, and has had all these obstacles he’s gone through,” Tom says of Wong. “But the first thing that drew me to him is that he is a Chinese person, living in America—an immigrant who against all odds became an artist in Hollywood, and very successfully”.

Tom knows firsthand about the obstacles women and people of color can face in Tinseltown’s film industry, more often hearing “what they can’t do,” she says. Tom graduated UCLA’s film school after completing her undergraduate at Brown University. She was named a Disney Fellow and later spent many years directing diversity programs to help filmmakers of color get a foothold in the industry. In all that time, she never heard of Tyrus Wong.

“I’m doing this documentary, in part, for the Chinese American people and other people of color,” she says. “His story is inspiring to people who want to know that there’s hope for even the most marginalized person pursuing a dream. He did it with resilience, with help from a lot of people, and by choosing his battles. His story will inspire a lot of people and make them proud.”

UPDATE: This article now reflects the new title of filmmaker Pamel Tom's documentary.

UPDATE: Originally, this article stated that as a young 9-year-old boy, Tyrus Wong was detained with his father at Angel Island. However, Wong's father had acquired legal status and so he was able to pass through immigration successfully, while Wong remained at Angel Island. Wong was promoted at Disney to the background department, but not to art director. We regret the errors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Joann_Stevens.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/9d/5a9d29e9-4202-45e8-afd9-6c37621a9069/12-tyrus-wong-studio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/cd/f3cd553b-4190-45df-ac57-192d587058fa/17-tyrus-wong-pam-tom.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/1d/df1dbbbb-c27d-40d7-bd94-c6a7e2923330/14-tyrus-wong-kite-owl.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/9a/c19ae417-8950-4b6b-8461-f115d7ee2b05/13-tyrus-wong-kite-studio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/53/e353e207-769a-4b02-a273-5ada6b90259f/01-bambi-tyrus-wong-4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/9d/9a9d03c3-9e4c-49e5-9e82-39ec3d02fbf5/11-tyrus-wong-horses-painting.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/56/e3569c39-4df2-4274-895d-db41fff2837b/10-tyrus-wong-christmas-card.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/5e/9e5e75c3-53c8-4a6a-b5aa-00c29f71e739/09-tyrus-wong-self-portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/c4/3cc48d7e-ffbf-438a-8711-e0e34e44ad42/08-tyrus-wong-newsboy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Joann_Stevens.jpeg)