How a Ragtag Band of Reformers Organized the First Protest March on Washington, D.C.

The first March on Washington was a madcap affair, but in May of 1894, some 10,000 citizens descended on D.C., asking for a jobs bill

The first march on Washington did not go well. It took place one hundred twenty years ago on May 1, 1894, when a throng of petitioners and reformers known as “Coxey’s Army” converged on the U.S. Capitol to protest income inequality. Thousands took to the nation’s roads and rails—even commandeering dozens of trains—to descend en masse on Congress.

When they arrived in Washington, the police cracked a few heads and threw the leaders in jail; but the mass movement polarized America–inspiring the poor and alarming the rich.

The year before the 1894 march, the economy had crashed catastrophically. Unemployment shot up to over ten percent and stayed there for half a decade. In an industrializing economy, the very idea of joblessness was new and terrifying. There was no safety net, no unemployment insurance and few charities. A week without work meant hunger.

Suddenly panhandlers were everywhere. Chicago prisons swelled with men who purposefully set out to be arrested just to have a warm place to survive the winter. The homeless were blamed for their circumstances, thrown into workhouses for “vagrancy,” punished with 30 days of hard labor for the crime of losing their job. The wealthy took little pity. The fashionable attended “Hard Times Balls,” where a sack of flour was awarded to the guest wearing the most convincing hobo costume.

Jacob Coxey, a witty Ohio businessman and perennial candidate for office, thought he had a solution. He proposed a “Good Roads Bill,” a Federal project to help the unemployed and to give the poor the work that they needed, while also helping to maintain and improve America’s infrastructure. Coxey’s idea was radically ahead of its time—four decades ahead of FDR’s New Deal programs. But Coxey had faith in his plan, declaring: “Congress takes two years to vote on anything. Twenty-millions of people are hungry and cannot wait two years to eat.”

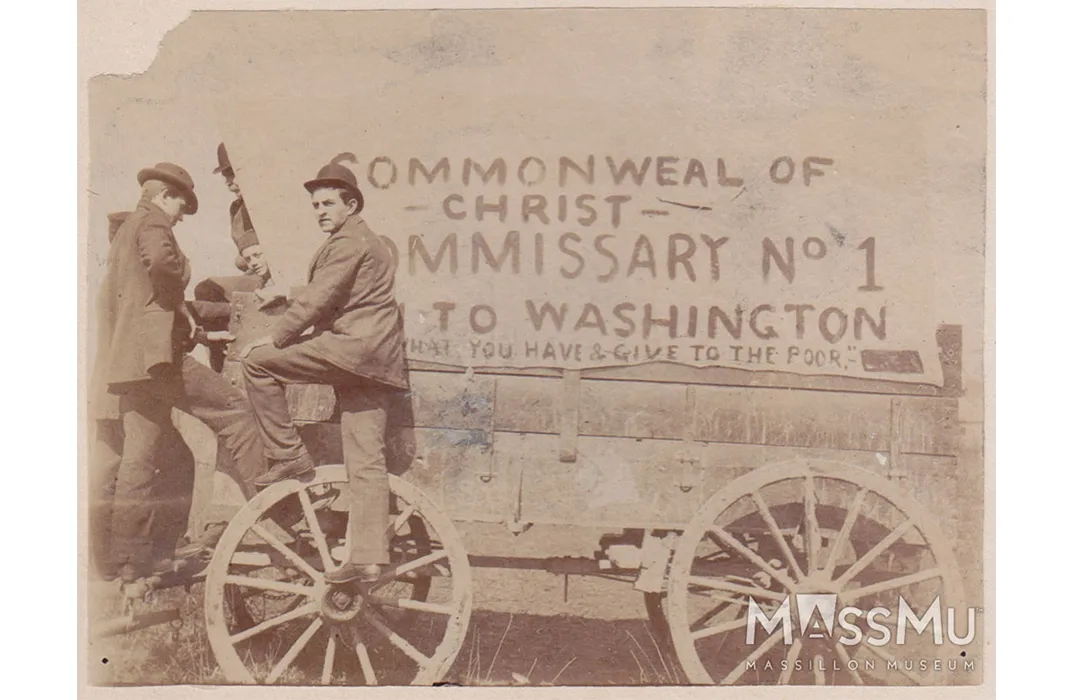

Coxey sought out help from one of the Gilded Age’s greatest eccentrics. Carl Browne was a hulking ex-con, an itinerant labor leader and a mesmerizing speaker. A guest at Coxey’s farm and oddly dressed in fringed buckskin suit, he’d marched around, pronouncing that Coxey had been Andrew Jackson in a past life. Browne considered himself the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, and asked that admirers call him “Humble Carl.” His eye for spectacle also made him a brilliant promoter. Together with Coxey, he planned a pilgrimage to Capitol Hill to present their Good Roads Bill, a $500 million Federal jobs plan.

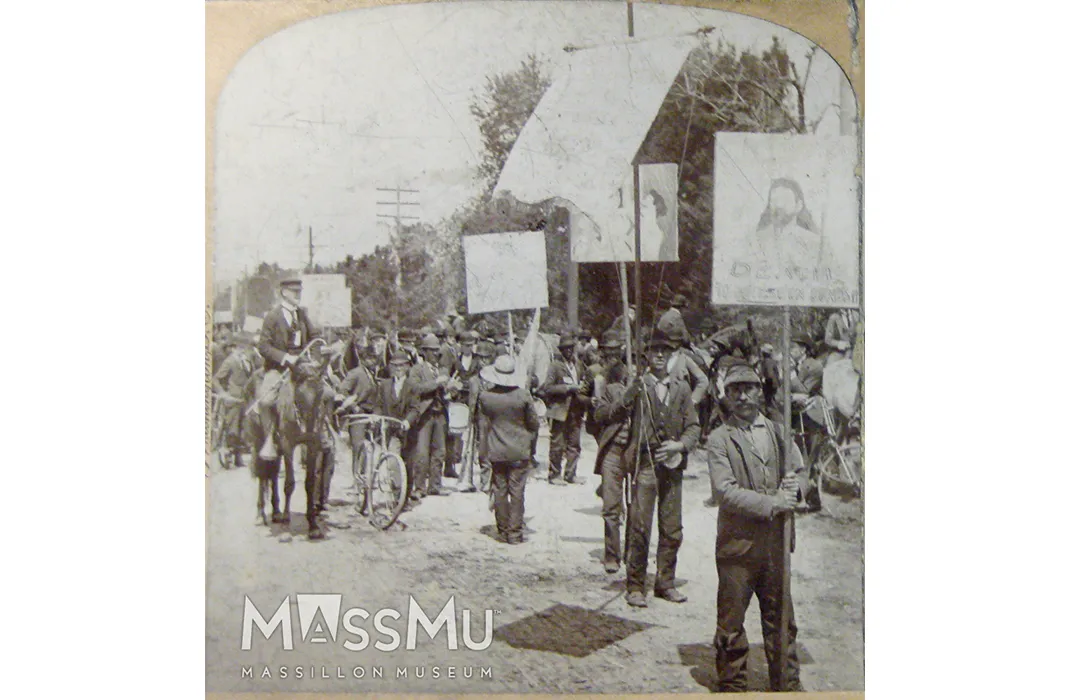

Soon Coxey and Browne were leading a “ragamuffin pageant” of unemployed workers, spiritualists, women dressed as goddesses, thoroughbred horses, collies and bulldogs from Massillon, Ohio, to Washington, D.C., waving peace flags and Browne’s (confusing) religious banners. The marchers camped outside of small towns along the way, surviving on donations of bologna and coffee and playing baseball with local supporters.

Journalists joined this ragged legion, breathlessly reporting exaggerations about “the Army” nationwide. Readers loved the story. Coxey and Browne had found a way to make the depressing social crisis into a thrilling narrative, turning gnawing poverty, in the words of historian Carl Schwantes, into “an unemployment adventure story.”

News of the march was especially welcome on the West coast, where the 1893 depression hit isolated boomtowns hard. California authorities had a cruel solution: simply throwing the unemployed on trains bound for the Utah or Arizona territories. To the rootless men and women squatting in hobo camps outside San Francisco or Los Angeles, marching on DC sounded like a fine idea.

“Armies” of out-of-work men and women began streaming cross-country—through deserts, over mountains and rafting the Mississippi. Hundreds hopped trains, infuriating the dictatorial railroad corporations that controlled western infrastructure. To teach these “bums” a lesson, one Southern Pacific locomotive stopped in west Texas, uncoupled the cars holding 500 demonstrators and chugged off, leaving the men stranded in the middle of the desert for nearly a week.

In Montana, out-of-work miners struck back, stealing a whole train and leading federal deputies on a 340-mile railroad-chase across the state. Townspeople helped the miners switch engines and refuel at key junctions. And they blocked their pursuers’ train, fighting the deputies and leaving several dead. Finally, Federal Marshalls peacefully captured the fugitives, but the wild news inspired more than 50 copycats to steal locomotives throughout the nation. Despite these clashes, most of Coxey’s marchers were peaceful. Alcohol was banned in their camps, which often hosted white and black marchers living together, and “respectable” women joined the western armies.

Yet to the wealthy and powerful, Coxey’s marchers looked like the first phase of the much-predicted class war. Authorities had little sympathy for these “idle, useless dregs of humanity,” as the New York police chief put it. Chicago and Pittsburgh banned marchers from entering city limits, and the Virginia militia burned their camp outside of Washington. Treasury officials panicked as the May 1 date of the march approached, arming even their accountants and preparing to fend off Coxey’s peaceful marchers.

For the main column of marchers, the greater threat came from within. Jacob Coxey was a mild man, more interested in raising horses than storming barricades. That left Carl Browne to lead, and he rubbed almost everyone the wrong way. Soon another charismatic oddball—a strikingly handsome, uniformed young man known only as “The Great Unknown”—challenged Browne for control. There was a tense showdown as the army camped in the Appalachians, with The Great Unknown calling Browne a “fat-faced fake” and threatening to “make a punching bag out of your face.” Coxey intervened, siding with Browne, and the Great Unknown receded into the background.

Not everyone found Carl Browne so objectionable. Jacob Coxey had a daughter. Mamie was 17, bubbly and beautiful, with lustrous auburn hair and flashing blue eyes. She joined the procession—some say she ran away from her mother, Coxey’s ex-wife – as it moved toward Washington. Few noticed it, with everything else going on, but Mamie Coxey spent a lot of time around Carl Browne.

By now Coxey’s “petition in boots” had reached Washington. As they camped near Rock Creek Park, many warned the marchers not to approach the Capitol. Police prepared to enforce a long forgotten law making assembling on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol illegal. But Coxey was intent on reading his Good Roads Bill from the people’s house. Smiling, he asked whether “preservation of the grass around the Capitol is of more importance than saving thousands from starvation,” and headed for Congress.

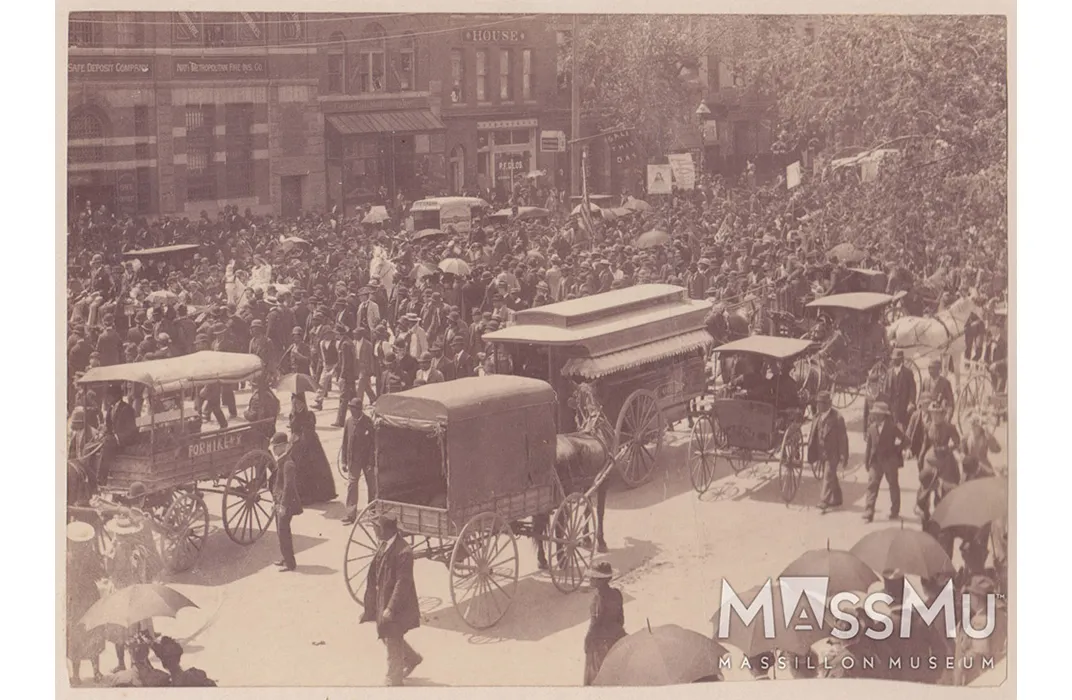

On May 1, 1894, tens of thousands turned out to watch the spectacle. Washington’s black community was especially interested. Locals knew about Browne’s showmanship and many wanted to see what he had in store. So did about one thousand policemen, assembled and at the ready. The sympathetic chanted “Coxey! Coxey! Coxey!” as the marchers arrived. They were not disappointed. At the head of the banner-waving procession rode “the Goddess of Peace” – the elegant young Mamie Coxey, dressed all in white, her copper hair flowing, perched on a white Arabian stallion.

When the authorities moved to halt Coxey and Browne at the Capitol steps, the two launched a daring plan. Big, noisy Carl Browne, ostentatiously done up in his buckskin cowboy costume, quarreled with the police then bolted into the crowd. Who wouldn’t want to clobber that guy? The cops chased “Humble Carl,” threw him to the ground and beat him. They proudly cabled the White House that Browne “received a clubbing.”While they were distracted, Coxey climbed the Capitol steps and started to read his bill. But he was quickly stopped. Police then turned on the crowd with sticks raised, beating the crowd back. It was over in 15 minutes.

The crowds dispersed. Coxey and Browne were sentenced to 20 days in a workhouse for trampling Congressional shrubbery. Many of the marchers simply traded homelessness in Cleveland for homelessness in Washington. It could have been worse, in an era when detectives shot strikers and anarchists threw bombs, but to the eager petitioners, it looked like a total failure.

The year after the march, Coxie’s daughter, the 18-year-old Mamie eloped with the 45-year-old Carl Browne. The marriage devastated Coxey and thrilled the newspaper gossips, but it couldn’t have been easy to spend time with the scheming, speechifying Carl Browne. The couple later separated.

But 50 years later, the former radical Jacob Coxey was invited back to Washington, hailed now as a visionary. This time, under FDR’s New Deal congress, his wild scheme was now to become the official policy of the United States. On May 1, 1944, Coxey was at last asked to read his petition from the steps of the U.S. Capitol:

We have come here through toil and weary marches, through storms and tempests, over mountains, and amid the trials of poverty and distress, to lay our grievances at the doors of our National Legislature and ask them in the name of Him whose banners we bear, in the name of Him who plead for the poor and the oppressed, that they should heed the voice of despair and distress that is now coming up from every section of our country, that they should consider the conditions of the starving unemployed of our land, and enact such laws as will give them employment, bring happier conditions to the people, and the smile of contentment to our citizens.

That first march on Washington tells the very human story of how America slowly reformed itself after the Gilded Age. Jacob Coxey and his bizarre and ragtag army of some 10,000 jobless followers and reformers, proposed one farsighted solution and many, many weird ones. But his lasting legacy? The many marches on Washington—an American cultural touchstone—have long since usurped the law to keep reformers from trammeling the lawn at the U.S. Capitol.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/67/ef673800-b72e-41f7-a04f-baf89ecb6984/03738u.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/4d/a14d5c99-fc3c-44d5-ab66-c4c168914ac9/ih162615.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/9d/f09d12ea-0c6d-4d61-abe8-4dde744c567c/ih184206.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/6f/606f91c3-6fb4-4c5d-be14-a5fde70c6bf0/u596020inp.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/6a/1d6a5db1-4d7f-4a29-ab6b-71777917044c/852512_along_tusc_river_1914.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/88/0788bbdc-68eb-4a36-9b36-0bd70b204b8a/9173215_a_coxeys_march.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/53/0d535062-945c-4acb-a331-4ce1faefab5f/js_coxey.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)