How the Story of ‘Moana’ and Maui Holds Up Against Cultural Truths

A Smithsonian scholar and student of Pacific Island sea voyaging both loves and hates the new Disney film

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/4d/ec4d7a4d-f8ec-477b-a919-b8e4c3d8baec/moana-disney-still-new.jpg)

I’ve said it before and I will say it again: the colonization of Pacific Islands is the greatest human adventure story of all time.

People using Stone Age technology built voyaging canoes capable of traveling thousands of miles, then set forth against the winds and currents to find tiny dots of land in the midst of the largest ocean on Earth. And having found them, they traveled back and forth, again and again, to settle them—all this, 500 to 1,000 years ago.

Ever since Captain Cook landed in the Hawaiian Islands and realized that the inhabitants spoke a cognate language to those of the South Pacific islands, scholars and others have researched and theorized about the origins and migrations of the Polynesians.

The Hōkūleʻa voyaging canoe has proved the efficacy of traditional Oceanic navigation since 1976, when it embarked on its historic maiden voyage to recover the lost heritage of this ocean-sailing tradition. The general scholarship on migrations seems well established, and most current researches now seek to understand the timing of the various colonizations.

But one huge mystery, sometimes called “The Long Pause” leaves a gaping hole in the voyaging timeline.

Western Polynesia—the islands closest to Australia and New Guinea—were colonized around 3,500 years ago. But the islands of Central and Eastern Polynesia were not settled until 1,500 to 500 years ago. This means that after arriving in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga, Polynesians took a break—for almost 2,000 years—before voyaging forth again.

Then when they did start again, they did so with a vengeance: archaeological evidence suggests that within a century or so after venturing forth, Polynesians discovered and settled nearly every inhabitable island in the central and eastern Pacific.

Nobody knows the reason for The Long Pause, or why the Polynesians started voyaging again.

Several theories have been proposed—from a favorable wind caused by a sustained period of El Niño, to visible supernovas luring the stargazing islanders to travel, to ciguatera poisoning caused by algae blooms.

Enter Moana, the latest Disney movie, set in what appears to be Samoa, even though most American audiences will see it as Hawaii.

Moana—pronounced “moh-AH-nah,” not “MWAH-nah” means “ocean”—and the character is chosen by the sea itself to return the stolen heart of Te Fiti, who turns out to be an island deity (Tahiti, in its various linguistic forms, including Tafiti, is a pan-Polynesian word for any faraway place).

The heart of Te Fiti is a greenstone (New Zealand Maori) amulet stolen by the demigod Maui. An environmental catastrophe spreading across the island makes the mission urgent. And despite admonitions from her father against anyone going beyond the protective reef, Moana steals a canoe and embarks on her quest.

But as should be expected whenever Disney ventures into cross-cultural milieus, the film is characterized by the good, the bad and the ugly.

Moana’s struggle to learn to sail and get past the reef of her home island sets the stage for her learning of true wayfinding. It also shows traces of Armstrong Sperry’s stirring, classic book Call It Courage, and Tom Hanks's Castaway.

But the film's story also has a different angle with a powerful revelation: Moana’s people had stopped voyaging long ago, and had placed a taboo—another Polynesian world—on going beyond the reef.

With the success of Moana’s mission and her having learned the art of wayfinding, her people start voyaging again.

And so the Long Pause comes to an end, Disney style, with a great fleet of canoes setting forth across the ocean to accomplish the greatest human adventure of all time. I admit to being moved by this scene.

As someone who lectures on traditional oceanic navigation and migration, I can say resoundingly that it is high time the rest of the world learned this amazing story.

But then there is much to criticize.

The depiction of Maui the demigod, who helps Moana on her journey, is a heroic figure found throughout much of Polynesia credited with performing a range of feats for the good of humankind.

Traditionally, Maui has been depicted as a lithe teenager on the verge of manhood. But the Maui character of this film, voiced by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson—recently touted as People magazine’s “sexiest man alive,” is illustrated as a huge buffoon and comes off as sort of stupid. Critics have noted that this depiction of Maui "perpetuates offensive images of Polynesians as overweight."

As my Native Hawaiian friend Trisha Kehaulani Watson-Sproat says, “Our men are better, more beautiful, stronger and more confident. As much as I felt great pride in the Moana character; as the mom of a Hawaiian boy, the Maui character left me feeling very hurt and sad. This is not a movie I would want him to see. This Maui character is not one I would want him to watch and think is culturally appropriate or a character he should want to be like.”

Tongan cultural anthropologist Tēvita O. Kaʻili writes in detail about how Hina, the companion goddess to Maui, is completely omitted from the story.

“In Polynesian lores, the association of a powerful goddess with a mighty god creates symmetry which gives rise to harmony, and above all, beauty in the stories,” he says. It was Hina who enabled Maui to do many of the feats he uncharacteristically brags about in the film’s song “You’re Welcome!”

The power and glory of this goddess is beautifully presented in the poem “I am Hine, I am Moana” by Tina Ngata, a New Zealand Māori educator.

Another depiction that is tiresome and cliché is the happy natives with coconuts trope. Coconuts as the essential component of Pacific Island culture became a comedy staple on the 1960s television series "Gilligan’s Island," if not before. They are part of the shtick of caricatures about Pacific peoples.

Not only do we see the villagers happily singing and gathering coconuts, but a whole race of peoples, the Kakamora, is depicted as, well, coconuts. This is a band of pirates that Moana and Maui encounter. Disney describes them as “a diminutive race donning armor made of coconuts. They live on a trash-and-flotsam-covered vessel that floats freely around the ocean.”

In the film, their vessels resemble “Mad Max meets the Tiki Barge,” complete with coconut palms growing on them. Disney’s Kakamora are mean, relentless at getting what they want, and full of sophisticated technology. And utterly silly at the same time.

But in fact, the Kakamora have actual cultural roots: they are a legendary, short-statured people of the Solomon Islands. Somewhat like the menehune of Hawai‘i, and bear no resemblance to the Disney knock-off.

“Coconut” is also used as a racial slur against Pacific Islanders as well as other brown-skinned peoples. So depicting these imaginary beings as “coconut people” is not only cultural appropriation for the sake of mainstream humor, but just plain bad taste.

Disney folks say they did their homework for this film, creating an allegedly Pacific Islander advisory board named the Oceanic Story Trust.

But as Pacific Island scholar Vicente Diaz from Guam writes in his damning critique of Disney’s exploitation of Native cultures: “Who gets to authenticate so diverse a set of cultures and so vast a region as Polynesia and the even more diverse and larger Pacific Island region that is also represented in this film? And what, exactly does it mean that henceforth it is Disney that now administrates how the rest of the world will get to see and understand Pacific realness, including substantive cultural material that approaches the spiritual and the sacred.”

Diaz also criticizes, quite rightly, the romanticization of the primitive that characterizes Disney movies like Moana, thereby whitewashing how those same peoples were colonized and their cultures dismembered by the West.

This glorification of native peoples striving to save their island from environmental catastrophe stands in stark contrast to the actions currently underway at Standing Rock, where Native Americans and their allies are being attacked, arrested, and sprayed with water cannons (in the freezing cold) for trying to defend their water sources and sacred lands.

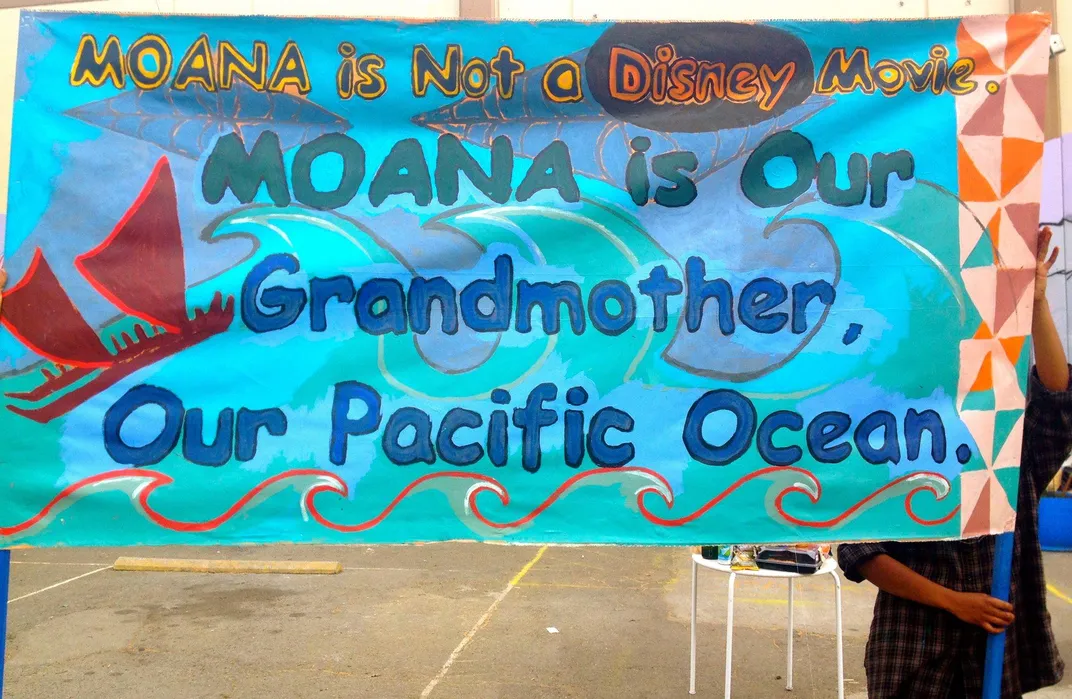

In short, Moana is not an Indigenous story, as New Zealand educator Tina Ngata points out. “Having brown advisers doesn’t make it a brown story. It’s still very much a white person’s story.”

In fact, many Pacific Islands remain in some neocolonial relationship with the powers that conquered them. And even the great feat of navigation and the peopling of the Pacific was discounted by scholars up until 1976, on the grounds that Pacific Islanders weren’t smart enough to have done it.

It took Hōkūleʻa to prove them wrong.

That said, and for all the bad and the ugly in this film—enough to provoke a Facebook page with thousands of followers—there is still inspiration and entertainment to be found here. Setting the cultural cringe factor aside, the film is entertaining and even inspiring. The Moana character is strong and her voice (portrayed by Auli‘i Cravalho) is clear and powerful. Most exciting of all, for this viewer, is the engagement with navigation and wayfinding.

As Sabra Kauka, a Native Hawaiian cultural practioner, said to me, “We sailed the great ocean in wa‘a [canoes] using the stars, the wind, the currents, as our guides. Hey, this is some kind of accomplishment to proud of!”

“I particularly like that the heroine had no romantic link to a man,” Kauka notes. “I like that she was strong and committed to the cause of saving her community.” She points out the kapa (Samoan siapo—traditional bark cloth) costumes and how the credits scroll over a piece of kapa.

There are other details that greatly enrich the story. The traditional round fale (Samoan houses), the father’s pe‘a (traditional body tattoo) and a scene showing the art of traditional tattooing (tattoo, incidentally, is a Polynesian word). And of course the canoes themselves in painstaking detail. The music provided by the Samoan-born artist Opetaia Foa'i, whose parents came from Tokelau and Tuvalu, adds a distinctly island flavor to an otherwise culturally-indistinct soundtrack.

And with Hōkūleʻa traveling around the world using traditional oceanic navigation to spread its message of mālama honua (taking care of the Earth), the timing of this film is just right, even if other aspects of the movie are just wrong.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)