How World War I Planted the Seeds of the Civil Rights Movement

The Great War was a “transformative moment” for African Americans, who fought for the U.S. even as they were denied access to Democracy

:focal(2971x1800:2972x1801)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/df/32df7db0-cacf-4fe7-8a86-9469cee24076/g06385.jpg)

In early April 1917, when President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress seeking to enter the United States in the first World War, he urged the “world must be made safe for democracy.” A. Philip Randolph, the co-founder of the African-American magazine The Messenger, would later retort in its pages, “We would rather make Georgia safe for the Negro.”

The debate over democracy, and who it served in the U.S., was central to the black experience during the Great War. African Americans were expected to go abroad to fight, even though they were denied access to democracy, treated as second-class citizens and subjected to constant aggression and violence at home.

Randolph was at odds with other leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, who saw the war as an opportunity for African Americans to demonstrate their patriotism and who expected they’d be better treated after their return home. Writing in the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, Du Bois called on African Americans to “forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”

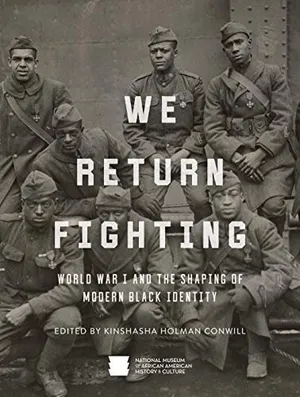

This tension frames the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s new exhibition, “We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity.” Focusing on both soldiers and civilians, the expansive show explores the experiences and sacrifices of African Americans during the war, and how their struggles for civil rights intensified in its aftermath. “World War I was a transformative event for the world,” says guest curator Krewasky Salter, who organized the show, “but it was also a transformative experience for African Americans.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/63/c2633f9c-5a09-4eca-b2fd-12381e395b9c/randolph.jpg)

More than four million Americans served in WWI, and nearly 400,000 of them were African Americans. The majority of black soldiers were assigned to Services of Supply (SOS) units and battalions, where they were responsible for retrieving and reburying dead American soldiers, building roads and railways and working the docks, among other demanding tasks. The thankless work of these troops was essential to the operation, and ultimate success, of the American Expeditionary Forces.

“While the SOS’s achievements were impressive—and essential—the American military remained far less efficient and effective than it would have been had it allowed more black soldiers to serve it combat,” Salter writes in the exhibition's accompanying book of the same title. “The accomplishments of those African Americans soldiers who did see battle make this point abundantly clear.” Members of the 369th Infantry Regiment, which spent more days in front-line trenches than other American outfits, received accolades for their bravery.

Although fighting for the same cause, African Americans faced racism and discrimination from white officers and soldiers. The cruelty and disrespect left its mark on servicemen like Lieutenant Charles Hamilton Houston, one of the nine black luminaries the exhibition highlights and whose revolver, diary and clock are on display.

We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity

We Return Fighting reminds readers not only of the central role of African American soldiers in the war that first made their country a world power. It also reveals the way the conflict shaped African American identity and lent fuel to their longstanding efforts to demand full civil rights and to stake their place in the country's cultural and political landscape.

After the war, Houston set out to ensure future generations of black soldiers wouldn’t suffer the same way. He attended Harvard Law School and later became the dean of Howard University’s law school, where he taught and shaped the next generation of black lawyers, including Thurgood Marshall. And in 1934, Salter writes, Houston “took on the US Army chief of staff, General Douglas MacArthur, over systemic racism in the military and the lack of officer position in the regular army for African Americans.”

The end of the war in November 1918 marked the moment of truth for Du Bois’ hope that African Americans would be welcomed back and better treated in the United States. A diary in the exhibition shares one young woman’s excitement to attend the parade for black soldiers, but reality set in. Du Bois would be proven wrong: Equal rights were not extended to African Americans and the violence against African Americans that had preceded the war continued and worsened after its end. Mob violence in more than 36 cities across the country and lasting from April to November 1919 earned the moniker “The Red Summer,” for the blood shed by targeted African Americans, including 12 veterans who lost their lives to lynching during that period. Similar to the retaliation that followed Reconstruction, the post-war era was defined by backlash and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/2a/7a2a8a0f-58c3-456d-8f8b-b0d3a43b2a65/g06214.jpg)

In 1919, Du Bois, both chastened and invigorated by what he witnessed during and after the war, understood the sustained struggle that lay ahead. “We sing: This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and dreamed, is yet a shameful land,” he wrote in The Crisis. “Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.”

The years that followed the end of the war were marked by white backlash and by black resistance. On display in the show is an iconic image of resistance: The NAACP’s banner declaring “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” From 1920 to 1938, it was hung outside the organization’s New York offices to announce every lynching. While the total number is not known, at least 3,400 Africans Americans were lynched in the century following the end of the Civil War.

The era also gave rise to a new identity—that of the “New Negro,” referenced and written about in Randolph’s The Messenger in contrast to the “Old Crowd Negro” like Booker T. Washington and Du Bois. Salter says, “The New Negro was a social, cultural, economic, political and intellectual rebirth of African Americans who went to fight for a country and were now unwilling to come live in the same America that they left.”

The United States was only in World War I for 18 months. That short time period and its overshadowing by the Second World War means WWI is somewhat of “an understudied and forgotten war,” Salter says. But its impact on the world and on African Americans cannot be underestimated. Here, the seeds of the civil rights movement were planted, he says.

The exhibition closes with an image and video from the 1963 March on Washington. At the side of Martin Luther King, Jr., stands one of the March’s co-organizers—A. Phillip Randolph, who more than 45 years before, understood that democracy abroad could not come at the expense of democracy at home.

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. Check listings for updates. “We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity” was scheduled to remain on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture through June 14, 2020.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.