Hustle through America’s Huckster History with a Smithsonian Curator as Your Guide

A blow by blow of the flimflams and tales of hustlers throughout history, art and literature

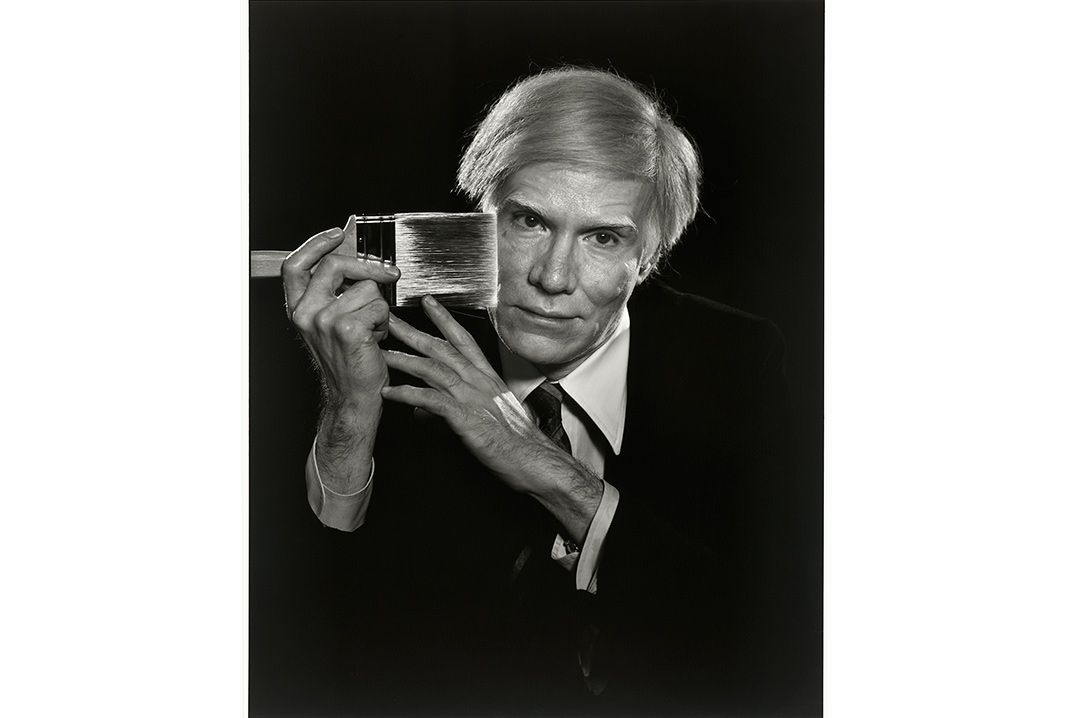

In 1962 Andy Warhol transformed cardboard Brillo grocery cartons into plywood and silkscreened replications that became art. Was he making a resonant cultural statement, or was he working his own playful con?

Warhol, a leading commercial artist, embraced Madison Avenue’s love of ambiguity and reconfigured it as art in the early 1960s. He understood the world where commercial images blurred the line between necessity and desire, between real and replicated. His was the age of “Is it real, or is it Memorex?”

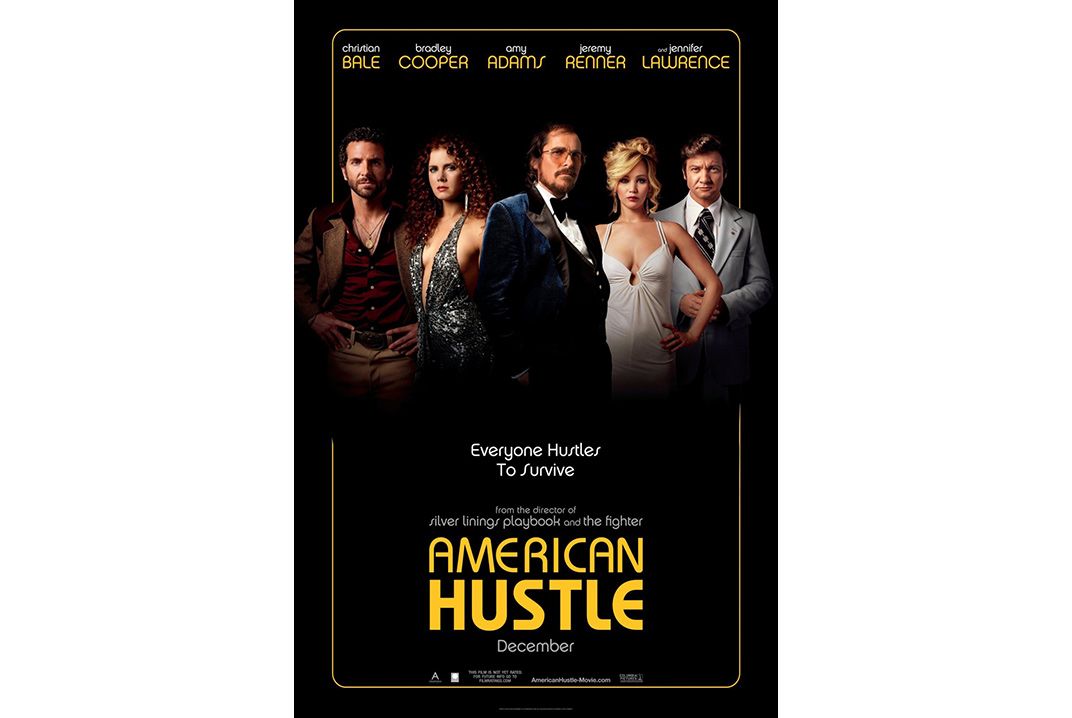

So the David O. Russell-directed film American Hustle fits right in. The film is emerging as a crowd favorite, having garnered three Golden Globes and ten Academy Award nominations. Loosely-inspired by the 1970s Abscam scandal, an FBI sting operation that snagged several members of Congress accepting bribes, American Hustle and its marvelous cast connects to America’s love affair with confidence men, hucksters and charming rascals.

We are enraptured by scoundrels. They showcase our passion for ingenuity and resourcefulness. Rules don’t matter in a culture that constantly reinvents itself. In the world of flimflam, con artists are American prototypes who exemplify the land of opportunity. Aren’t we all searching for the trickster Wizard at the end of the yellow brick road?

The sheer joy of American Hustle is its portrait of people who hustle. Christian Bale’s velvet suits and extravagant comb-over; Amy Adams’ plunging necklines (waistlines?); Jennifer Lawrence (Bale’s scene-stealing wife) in gowns that fluff-up with feathers and sparkle with rhinestones; Bradley Cooper (the beyond-the-fringe FBI agent) in his creepy suits and itty-bitty spit curls; and Jeremy Renner, his face marvelously distorted, as the well-meaning mayor of Camden who gets duped.

Costumes are central to creating their portrayals. In an interview with The New York Times, costume designer Michael Wilkinson said, “We wanted the actors to use their costumes as part of their hustle. They dress as the person they aspire to be.” Wilkinson explained that his approach was to use “silhouette, fabric, color, drape” to tell the story.

Our cultural history is pockmarked with colorful portraits of these characters. In the mid-19th century, the con artist was featured in Herman Melville’s last published book, The Confidence- Man: His Masquerade. Set on a riverboat traveling down the Mississippi River, the 1857 novel tells the tale of what happens when the Devil, dressed in disguise, boards the vessel to conduct the business of evil.

Melville wrote this book because he was outraged at the way America was allowing capitalism to nurture a culture of greed. The Confidence-Man is a complicated diatribe, but New York Times critic Peter G. Davis phrased it succinctly in a 1982 magazine article stating that the book was a “microcosm of America’s melting pot…a loosely knit collection of fables” in which the title character uses his guile to dupe each passenger on the riverboat. In each instance, the Confidence Man/Devil works a con against “the nineteenth century American Dream of optimism, truth, altruism and trust.”

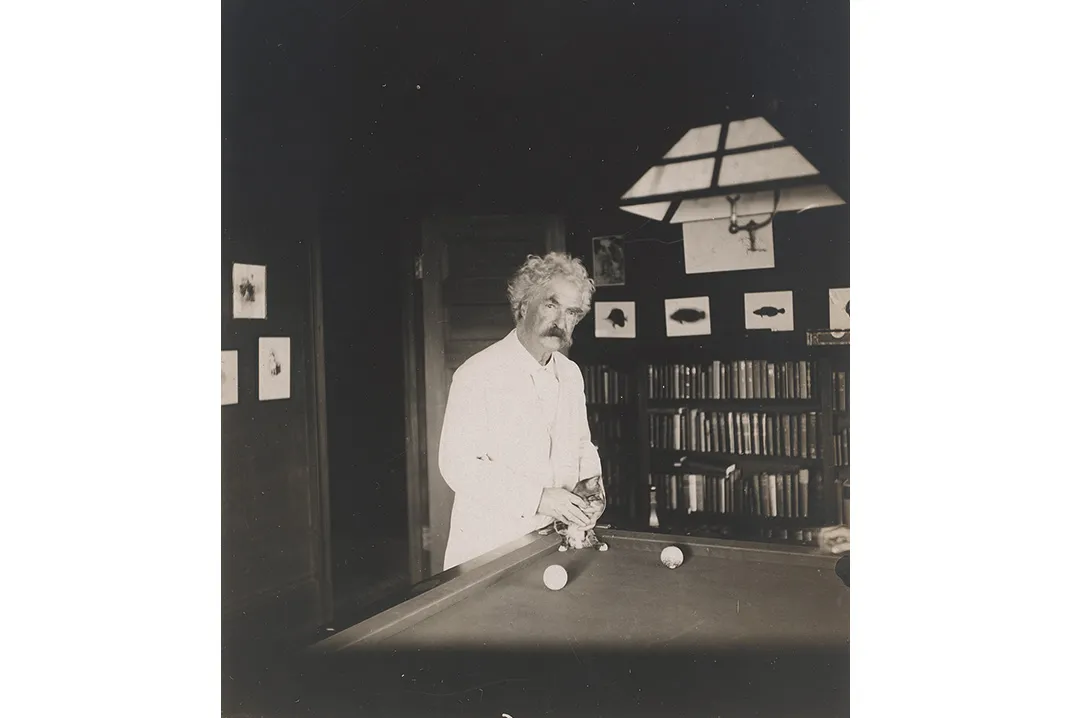

Mark Twain, too, took up the art of the con. Like Melville, he used Mississippi riverboats to stage the antics of his flimflam men. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn opens with Huck’s warning that while the author might sometimes stretch the truth, “he told the truth, mainly.” Twain relishes the art of the con and unleashes flimflam men throughout the novel, but he allows Huck to succeed: the boy’s instinct is sound, and his character remains unsullied by temptation. A recent assessment in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune suggests that “Huck Finn” is about the folly of ever trusting the fashionable morality of one’s own time and place. Any time, any place.”

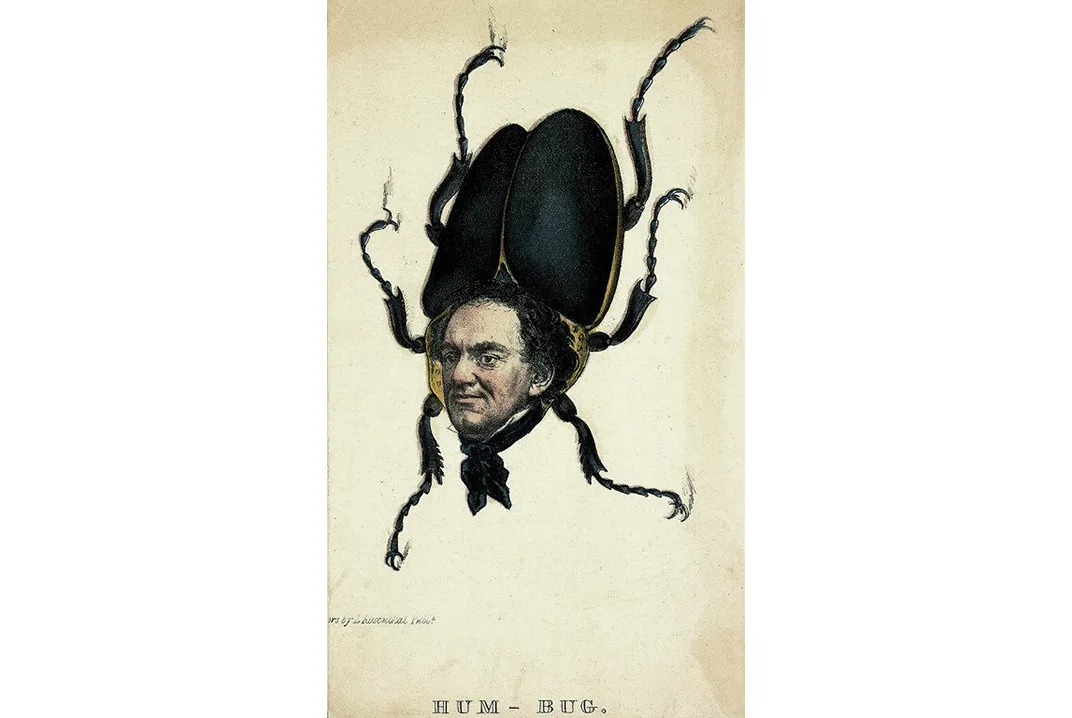

Con men weren’t always fictional. One of the greatest, P.T. Barnum, was the real deal. According to a 1973 biography of P.T. Barnum, Barnum was the pioneering impresario of “humbug” who helped invent mass entertainment; his mantra was to exploit the public’s desire to be flimflammed. From the 1840s to the 1870s, he organized popular New York museums that showcased “industrious fleas, automatons, jugglers, ventriloquists, living statuary, tableaux, gypsies, albinos, fat boys, giants, dwarfs, rope-dancers….”

Barnum happily faked events in order to generate free publicity for his museum. He wrote that the art of “the humbug” was to put on “glittering appearances…novel expedients, by which to suddenly arrest public attention, and attract the public eye and ear.” Novelty and ingenuity were essential to his commercial success, his biography said, and if his "puffing was more persistent, [his] flags more patriotic” it wasn’t because of fewer scruples, but more ingenuity. The glitter and noise created outside his museum drew crowds. Once inside, they could be entertained for hours by his displays, but they had to pay to get in—no one got something for nothing.

Confidence men continued to flourish in 20th century American literature, notably with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. But a new century provided fresh formats, and shill artists now appeared on stage and screen. In the 1927 Broadway sensation Show Boat, the male lead is the compulsive riverboat gambler Gaylord Ravenal; meanwhile Gone With the Wind's Rhett Butler displays in noncommittal attitude and in snappy costume his earlier life as a professional gambler turned blockaid runner and speculator.

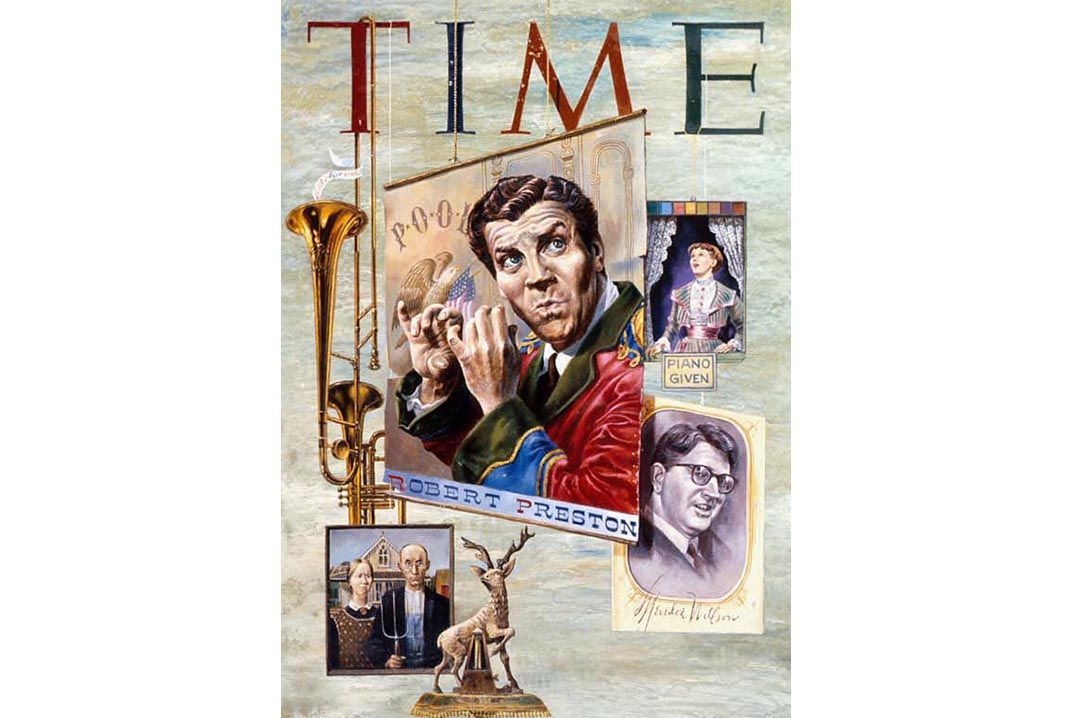

On the lighter side of the con, flimflam was Professor Howard Hill’s animating purpose in Meredith Willson’s Tony-award winning 1957 musical The Music Man. Robert Preston’s unmatchable portrayal of Professor Hill, who comes into town on a tear and warns of “trouble."

With a capital "T"

That rhymes with "P"

And that stands for Pool,

Scam artistry was also the focal point for the delightful 1973 Paul Newman and Robert Redford caper, The Sting. Set in Depression America in 1936, the plot focuses on two professional grifters (Newman and Redford) who launch a “big con” that eventually includes a vicious crime boss, a bookie, an undercover FBI agent, a waitress and…well, the plot is thick with colorful and scary characters. But the ragtime music by Scott Joplin is uplifting, and so is the film’s finale.

Con artists in the 1950s and ‘60s sometimes migrated from small towns and riverboats to Madison Avenue, where the world of advertising became their high stakes playground. Like their grifting and shilling predecessors, promulgators of Madison Avenue’s great pretend continued a well-honed American tradition. In slicked up versions of “humbug,” advertising agencies focused on product packaging, bolstered by clever jingles like “Plop plop/Fizz fizz/Oh What a Relief It Is” and “Does She, or Doesn’t She?”

Much like Warhol did by replicating Brillo boxes as art, Mad Men brilliantly reconstructs the world of Madison Avenue for today’s TV audiences. The show portrays the machinations of smarmy ad man Don Draper, whose dreams draw deeply from huckster roots and whose antics have made him a popular cultural anti-hero.

American Hustle is a happy addition to the nation’s flimflam repertory. Both heroic and ridiculous, the film celebrates the grit and determination burrowed in America’s DNA. It’s really the story of people trying to find their dream—and we cheer them on because it’s our story, too.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)