I Was Among the Lucky Few to Walk in Space

On July 31, 1971, Al Worden performed the first deep-space extra-vehicular activity. “No one in all of history” saw what he saw that day

Apollo 15 was the first flight to the moon that included a space walk. On our return trip to Earth, we needed to recover film canisters from the service module where they were part of the Scientific Instrument Module Bay (SIM Bay). Because it was a new activity an incredible amount of preparation went in to the procedures and the equipment required to make it safe and efficient.

Also, because I was assigned to the flight after these procedures and equipment were identified and developed, I needed to evaluate the entire plan for the Extra-Vehicular Activity in terms of safety and results. So I changed the equipment and slightly altered the procedures to simplify the process. During our preflight analysis, we installed a warning tone in the suit in the event of low oxygen pressure or flow and we simplified the method of returning the canisters to the Command Module. Rather than use a complicated clothesline rigging method to return the canisters, we chose instead for me to simply hand carry the canisters back to Jim Irwin, who remained waiting in the hatch. Once all this preflight work was accomplished, the actual space walk was easy and accomplished in a short time. I had the pleasure of being outside the spacecraft for 38 minutes, and here's how we did it.

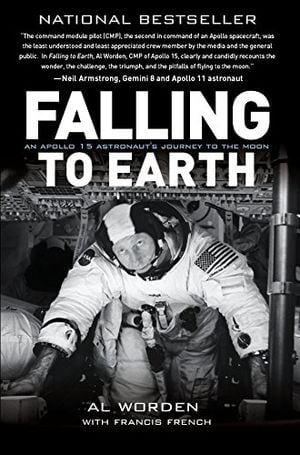

Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut's Journey to the Moon

As command module pilot for the Apollo 15 mission to the moon in 1971, Al Worden flew on what is widely regarded as the greatest exploration mission that humans have ever attempted. He spent six days orbiting the moon, including three days completely alone, the most isolated human in existence.

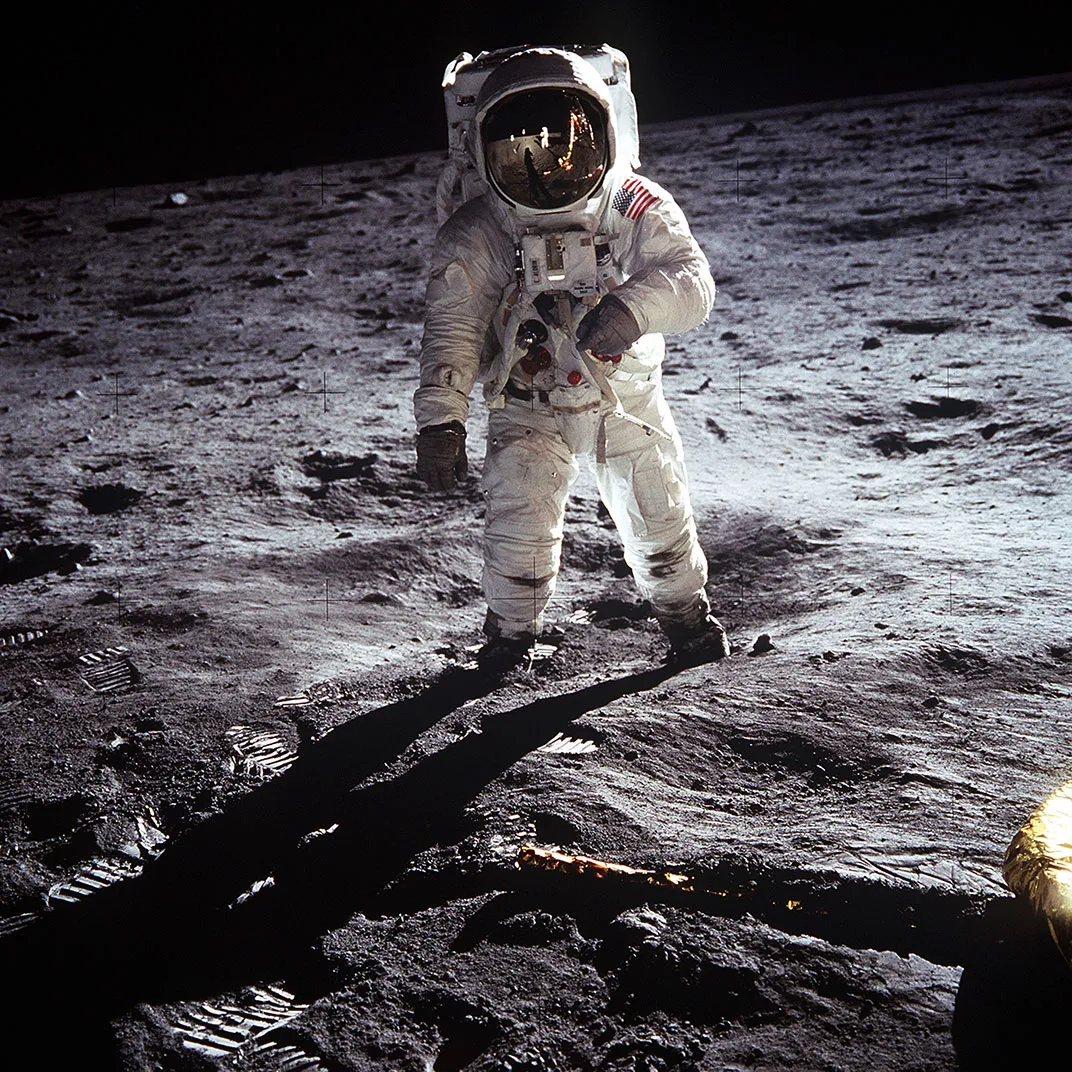

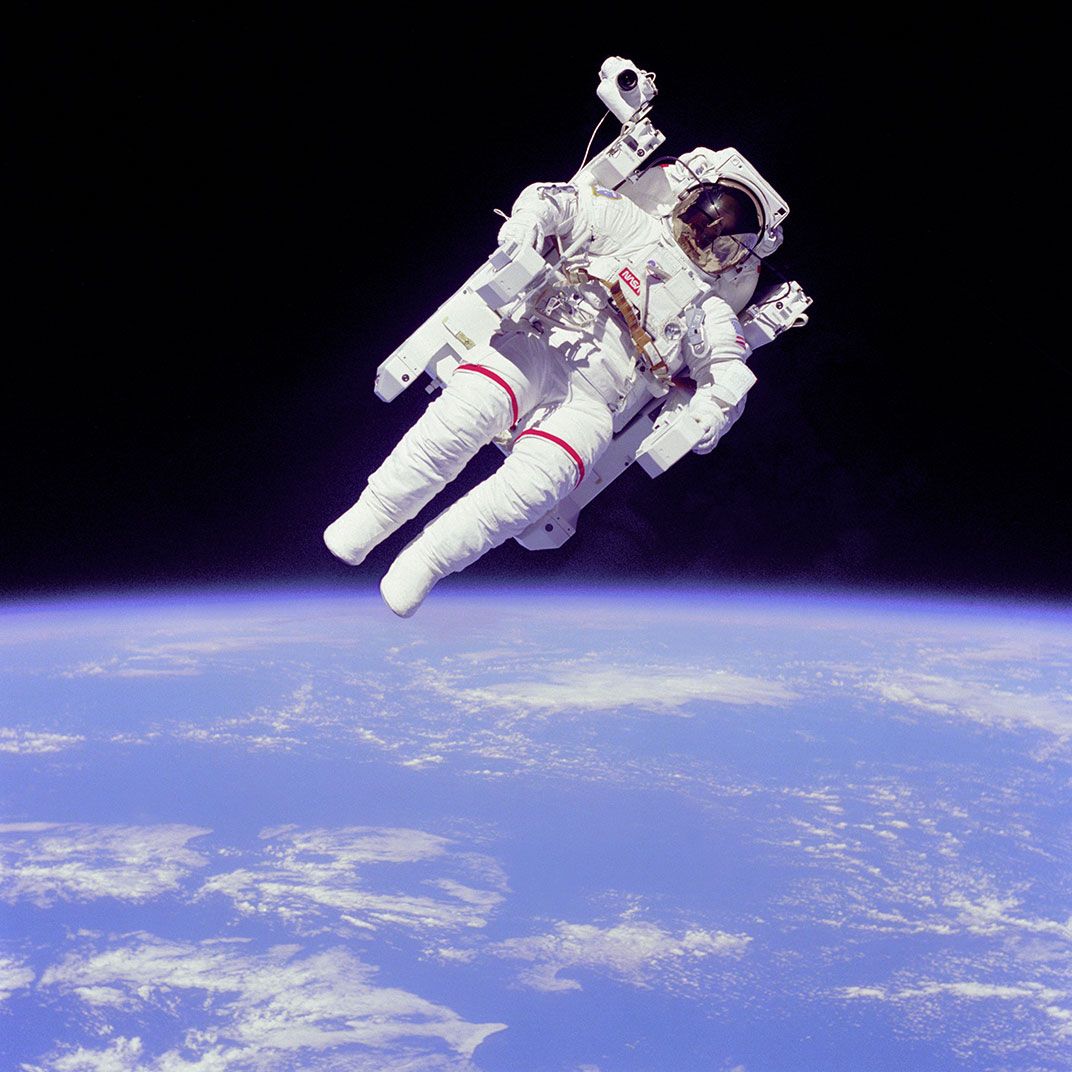

We started suiting up an hour or so before the actual EVA, checking out our pressure suits to make sure they were holding up, storing all the loose equipment in the Command Module, including removing the center seat, and going over the procedures we needed to follow. I got a little rush as the Command Module was depressurizing because I was then completely dependent on the pressure in the suit to keep me alive. I had practiced this procedure many times on Earth, but this was for REAL and I had to do it just right. Once the cabin pressure went to zero, we opened the hatch and looked out. Black as the ace of Spades, but as Jim and I floated out, there was enough sunlight to light our way. It was an unbelievable sensation. I described it once as going for a swim alongside Moby Dick. There was the CSM, all silvery white with very distinct shadows where equipment got in the way of the sunlight. I moved across the hatch carefully to make sure I could reach the handholds and maneuver in the bulky suit. Didn’t take long to get used to it, except for the fact that I was no longer inside.

What a feeling to be free in deep space about 196,000 miles from home. I could only hear what was inside the suit, such as my breathing and the occasional radio transmission. I was connected to the spacecraft by a tether called an umbilical cord because it contained all the things I needed to stay alive. Oxygen and radio communication were the most important. The oxygen system was interesting in that it was called an open loop system. That meant that the flow of oxygen into the suit was vented at a precise pressure to maintain suit pressure. So I could hear the whoosh of the O2 as it flowed through the suit. I concentrated on reaching for the handholds as I made my way to the back of the service module so I would not float away.

I had a small problem right away. The high-resolution camera was stuck out in its extended position. I had to go over the camera to get to the film canister. I was free floating out there, so I just turned around and backed over the camera with ease. I reached the canister, put a safety clip on it, attached by a tether to my wrist, and pulled it out of the bay. Turning around again I made my way back to the hatch where Jim took it and handed it to Dave Scott for storage. So far, a piece of cake.

The second trip out was pretty much like the first, except that I now had to get the canister from the mapping camera and take it back to Jim. I made a third trip to the back of the service module to take a good look around, and see if there was any damage. I could only see some scorching where the Reaction Control System fired during flight, but it was no big deal and it was mostly expected. I placed my feet in restraints and took just a moment to take in the view.

It was the most unbelievable sight one could imagine, and I was so proud of our ability and ingenuity as a nation to do something this magnificent. By turning my head just so I could position myself so that both the Earth and the Moon were in field of vision. I realized that no one in all of history had ever seen this sight before. What an honor it was.

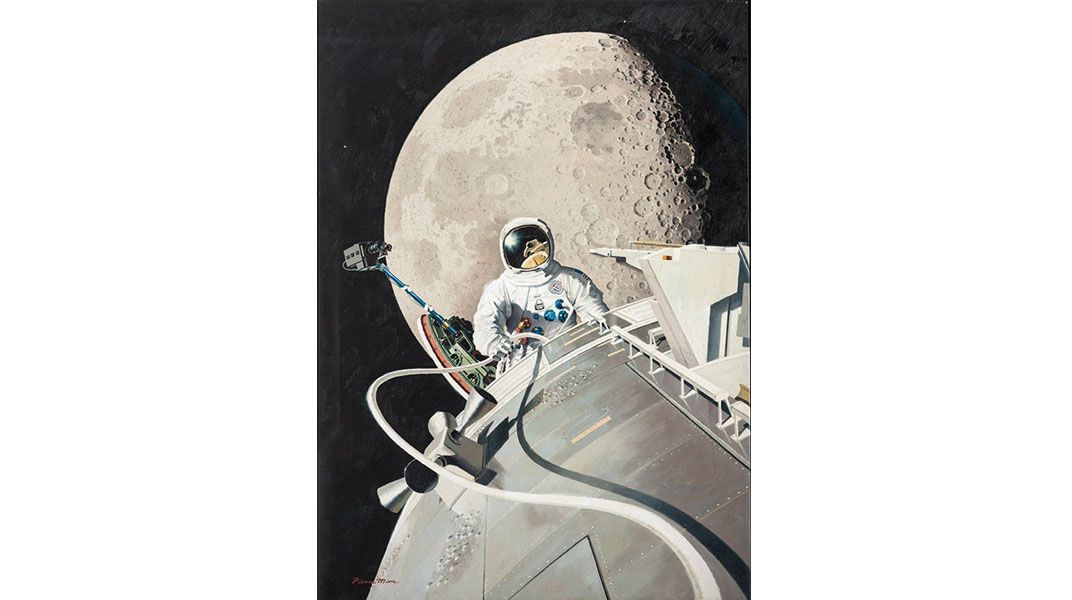

My biggest disappointment was that I was not allowed to carry a camera with me. Imagine today, with cell phone cameras everywhere, I couldn't even snap a photo of that wonderful view as a keepsake. But perhaps I did one better, because when we returned to Earth I had the privledge of working closely with an artist named Pierre Mion to carefully craft a scene that is remniscent of that magical moment. What you see in the painting is Jim Irwin in the hatch (which was my view from out there), and in his visor, if you look closely, you see my reflection. The Moon behind him became an iconic image of that EVA.

As the command module pilot for Apollo 15, the fourth manned lunar-landing mission, astronaut Al Worden became the 12th man to walk in space during his 1971 flight, when he logged 38 minutes in Extra-Vehicular Activity outside the Endeavour command module. His mission was to retrieve film from high resolution panoramic and mapping cameras that were recording about 25 percent of the moon's surface. Smithsonian.com invited Worden to recount the moment he first stepped outside the hatch and free-fell into space.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_0272WEB.jpg)