Why a Woman Is Playing the Same Guitar Chord Over and Over Again at the Hirshhorn

The absurdly comedic work of Iceland’s top performance artist Ragnar Kjartansson

When Ragnar Kjartansson studied painting at the Iceland Academy of the Arts at the dawn of the 21st century, it wasn’t so much the art that excited him, but the act of making the art.

“I use painting often as a performance,” the 40-year-old artist from Reykavik says. “And often it’s about the act of painting the painting rather than the result itself.”

So the performance of painting became part of his wide-ranging, theatrical and often quite musical works, which are getting a suitably entertaining retrospective in his first North American survey, “Ragnar Kjartansson,” newly opened at Washington D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

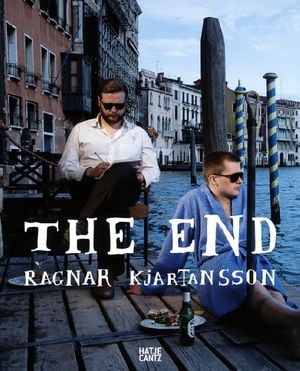

In it, the paintings are artifacts of performances he’s had, such as one at the Venice Biennale in 2009—when he painted 144 paintings of a Speedo-clad fellow Icelandic artist Páll Haukur Björnsson, one a day for six months.

Another work, Die Nacht der Hochzeit, repeats the image of an inky night of clouds and stars, a dozen times. In a third, Blossoming Trees Performance he presents seven plein air works he completed at the historic Rokeby Farm in upstate New York, that also includes a work chronicling the seven paintings he did in two days as well as his other activities (“smoked cigars, drank beer and read Lolita”).

It was Rokeby, too, where he returned for a far more epic work, the nine channel video performance The Visitors, in which Kjartansson, in a tub, leads a group of his musician friends in a long, improvisatory and ultimately thrilling performance of a work that repeats, over an hour, two lines from a poem by his ex-wife: “Once again I fall into my feminine ways” and “There are stars exploding and there is nothing you can do.”

Repetition is a hallmark of Kjartansson’s work. He assumes the role of an old school crooner in one performance, captured in a 2007 video, God, to repeat the line “sorrow conquers happiness.”

The melancholy that music can carry is the point, too, of the one live performance of the exhibition, Woman in E. A female rock guitarist in a gold lamé dress strums a single chord, E-minor, over and over as she spins slowly on a similarly gilded stage behind a curtain of golden strands.

Fourteen different rockers, mostly from D.C. but also from Richmond and Charlottesville, Virginia, were selected to perform the piece, in two-hour shifts.

It’s been done once before, earlier this year at Detroit’s Museum of Contemporary Art. But, Kjartansson says, “it seemed like such a perfect piece to do here, in this space and in relation to all the epic monuments around here. To be on the Mall with the Woman in E is really rad.”

Despite the inherent sadness of the repeated E-minor, humor is pervasive in the exhibition as well, from the beginning, when he presents himself in the character of “Death” to schoolchildren in a graveyard (who clearly aren’t buying the act), to the end, where his mother in four different videos shot in five year increments, spits at her son (at his request).

“We thought we had to end with a bit of punk rock,” Kjartansson says of the piece, Me and My Mother.

The lighthearted approach is necessary particularly in the art world, Kjartansson says at the museum, the echoing cacophony of his videos can be heard just behind him.

“Everything is so serious you have to be lighthearted about it,” he says. “Art is so serious, it’s too serious to be serious about.”

So even his most ambitious pieces, such as a staging of the Icelandic epic World Light—The Life and Death of an Artist which unfolds in four simultaneous life-sized videos playing opposite one another in a large room, has its melodrama that adapts the novel by Nobel Prize-winning Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness, undercut by shambling scenes in which Kjartansson runs through scenes naked.

“I’m very excited about World Light’s four screens,” the artist says. “There’s always this talk about beauty and art, but they’re all superficial. And if you scratch on the surface there is something.”

It would take nearly 21 hours to catch every frame of World Lights, but Stéphane Aquin, chief curator at the Hirshhorn, who helped organize the show first presented at London’s Barbican, notes that “you can stay there 10 minutes, an hour, or 30 seconds.”

Especially with some of the other pieces that loop in the show, “what’s great about art based on repetition is that you don’t have to stay for the whole length of it.”

What was challenging about organizing the mid-career retrospective was to give the pieces with sound and music enough space not to bleed on the other. Taking up a whole floor of the museum’s famous circular floorplan means starting and ending at the neon sign he once devised for a lonely rooftop in the countryside where Edvard Munch once painted in Moss, Norway, that reads Scandinavian Pain.

“The surroundings seemed like a Munch painting or a frame from a Bergman film, so I had to put that title up,” Kjartansson says.

“It’s so good to have it in a circle,” he says of the Hirshhorn layout. “We did the show in the Barbican in London and it was a very different narrative than here. That was square with rooms, but this is like really American—it’s almost like a computer game going through here.”

And America weighed heavily on all the pieces, though he is from Iceland.

“It’s like a recurring thing in my work: This idea of America,” Kjartansson says. “Probably because I was raised by good Communist parents who took me to rallies against America, it became a really big idea in my head.”

He says when he finally came to the states in 2002 he found it “exactly like in the movies.” Since then, he’s crisscrossed the country extensively. “I’m just always fascinated by it—this new land of immigrants.”

Acquin says he organized the show in roughly three parts—reflecting the artist’s hand, his staging and relationships—and the museum layout “allowed for a flow and for the story to unfold in a very narrative way, and a very cinematic way. It’s as if you were walking through a movie, and scene after scene, they all add up to this amazing moment, which is The Visitors, in the final corridor.

“There’s a buildup of emotion and ideas leading up to it,” Acquin says. “People come out of The Visitors crying, regularly.”

Although The Visitors is named after an ABBA album, Kjartansson and his musician friends play a hypnotizing song that’s much more along the lines of an Arcade Fire epic that unfolds with each musician playing in headphones in a separate room of the 19th-century Rokeby Farm mansion.

It’s an interactive work, such that a viewer who approaches the accordionist or drummer will hear that musician louder. Around a corner, a group sings harmonies on the porch, and flinches as the work reaches a climax that involves a canon firing.

It ends with the musicians individually abandoning their posts, joining Kjartansson as he leads them, Pied-Piper-like, down a lush Hudson Valley field while a technician stays back and switches off each camera one by one.

For the artist, seeing a collection of his works that were previously presented individually “is a really high feeling,” At the same time, “It feels like a new chapter after cleaning out the attic,” Kjaransson says.

And what will come next?

“I don’t know, I’m in a bit of a limbo,” Kjartansson says.

But a word of warning: it could be Hell. “I’m reading Dante’s Inferno now,” he says.

“Ragnar Kjartansson” continues at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through January 8, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/c1/cdc17e6f-b5b5-446c-b9f2-4cec3f31b758/womaneinstallation1web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)