If Only Ernie Had Seen It. Here’s Why “Mr. Cub” Is Part of the 2016 World Series Win

From Smithsonian Books, a treasure of baseball history for those who can’t wait for spring training

:focal(592x127:593x128)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/37/f137966e-c36b-4853-ab7e-fea741912caf/banks-2.jpg)

“Happiness is going eyeball-to-eyeball with those Cub fans. That's really what I appreciated most about playing in Wrigley Field.”

—Ernie Banks

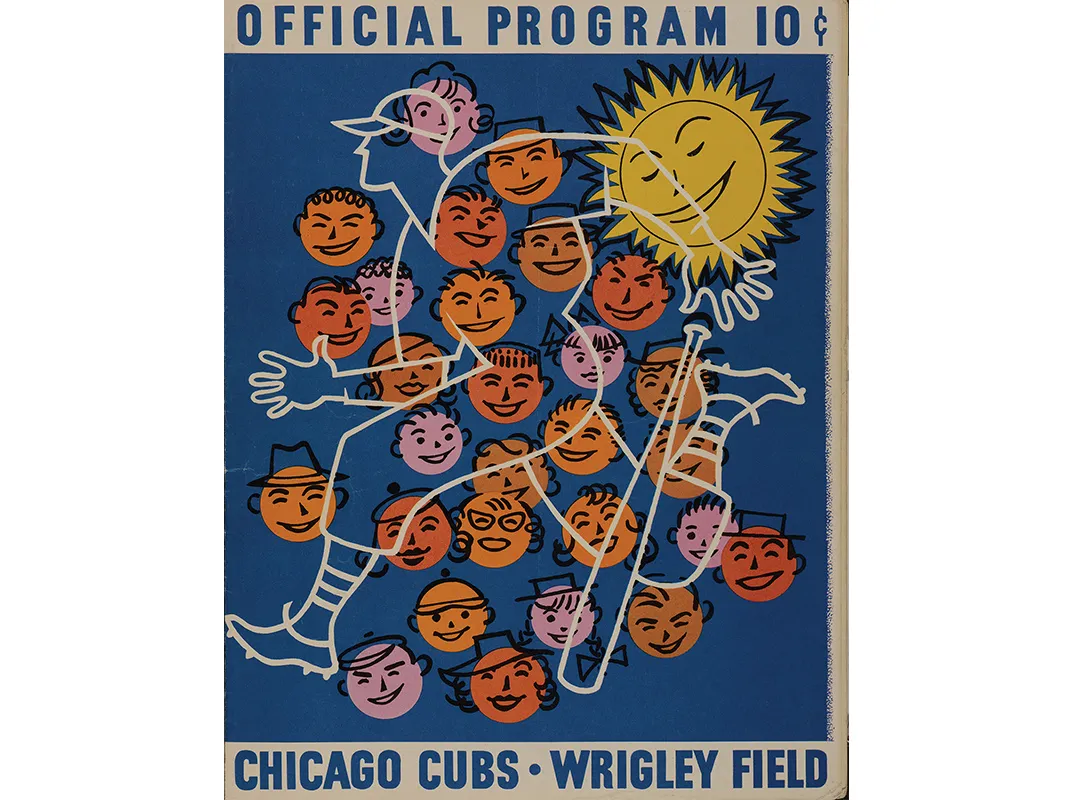

One of the great pleasures in life has to be having a hot dog and Coke at the ballpark. Imagine sitting in the bleachers at Wrigley Field on a sunny afternoon on May 24, 1957, before the start of a game between the Chicago Cubs and Milwaukee Braves. With the game’s scorecard—like the one shown here—on your lap, you bite into your frankfurter as you scan the grass in front of the ivy-covered brick outfield wall.

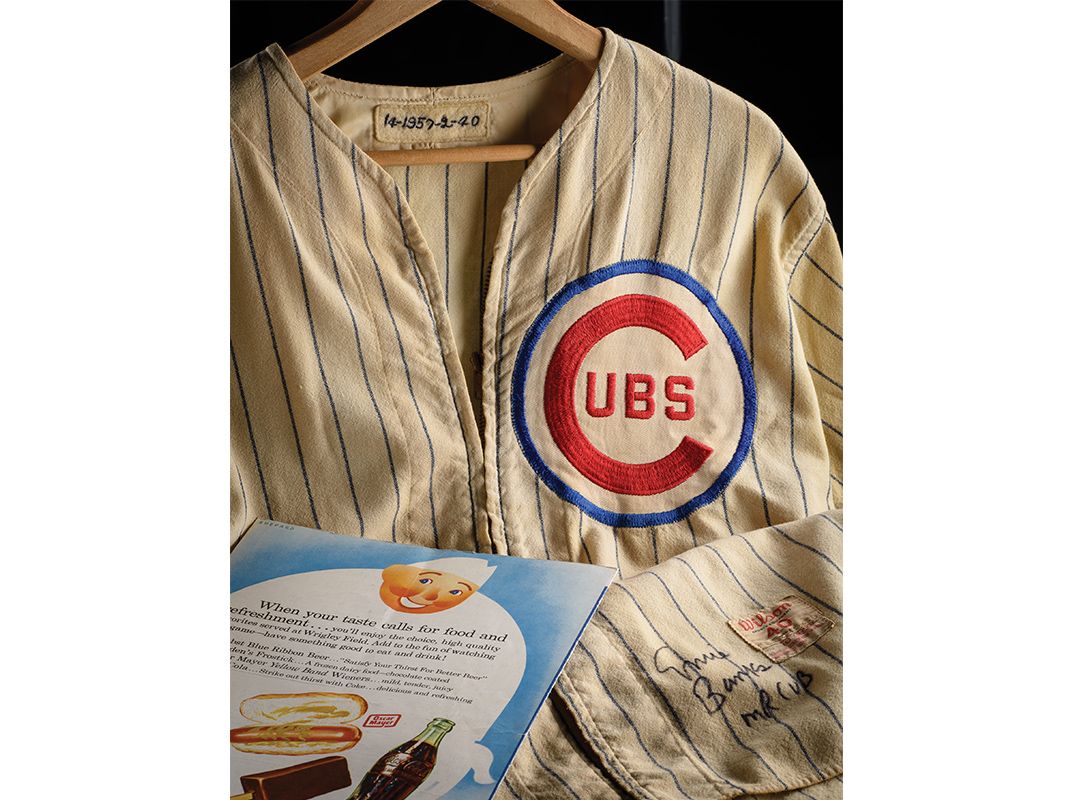

There, you see two giants of the game standing together in conversation. The first is Hank Aaron, who would become the National League’s MVP that year wearing his gray Milwaukee Braves road uniform. Next to him is a rising NL superstar, Ernie Banks, who would hit 43 home runs that season, wearing the Chicago Cubs home pinstriped flannel jersey also shown here. The jersey features a zipper front, which was first adopted by the Cubs in 1937. During the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, many teams used zippered jerseys instead of button front jerseys, while a handful of teams wore them into the 1970s and even the 1980s.

No player in the history of baseball has been so closely identified with a single city as Ernie Banks, a favorite of Chicago fans and known for much of his career as “Mr. Cub.” Less well known is that Banks, a migrant from the South, was a pioneer of civil rights in professional baseball, a living bridge between the Negro Leagues and the multiethnic but by no means post-racial game of today.

Born on January 31, 1931, in Dallas, Texas, Ernest Banks attended Booker T. Washington High School and excelled in football and basketball. The school did not offer baseball so Ernie played on a fast-pitch softball team in the church league, which fit nicely with his mother’s hopes that Ernie would become a minister.

When Banks was a high school sophomore, his skill on the field became evident to anyone who saw him play. He was introduced to the owner of the Detroit Colts, a travel team from Amarillo, Texas, which served as a feeder team for the Negro Leagues. Banks tried out for the Colts and became the team’s shortstop, traveling to games in Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma. When Banks was a high school senior, the Colts played the Kansas City Stars, and Banks impressed Stars manager “Cool Papa” Bell with his demeanor and his skill on the diamond. “His conduct was almost as outstanding as his ability,” said Bell, who promised Banks a job with the Kansas City Monarchs if he completed his senior year of high school. Bell recommended Banks to Buck O’Neil, the manager of the Monarchs.

The Monarchs offered Banks $300 a month, and Eddie and Essie Banks gave their consent for their son to become a professional ballplayer. In signing with the Monarchs, Banks joined one of the most storied teams in the Negro Leagues, a pillar of black baseball.

“‘Cool Papa’ Bell was the first one who impressed me,” Banks said later. “Buck O’Neil helped me in many ways. He installed a positive influence.” Banks joined the Monarchs in the middle of the 1953 season, after a two-year stint in the Army, and he played shortstop and batted .347 for the rest of the season.

Banks later said that “playing for the Kansas City Monarchs was like my school, my learning, my world. It was my whole life.” Banks played so well that he quickly caught the attention of the Cubs, who were making efforts to integrate. The Cubs wasted little time in signing Banks, and he made his major league debut on September 17, 1953.

Banks was the first African-American to play for the Cubs, and Jackie Robinson advised him to keep his head down and to be prepared for insults directed at him because of his ethnicity. Banks, naturally quiet, was happy to focus on baseball, but his reluctance to speak openly in favor of the civil rights movement led some activists to brand him an “Uncle Tom.” It did not help when Banks said, “I look at a man as a human being; I don’t care about his color. Some people feel that because you are black you will never be treated fairly, and that you should voice your opinions, be militant about them. I don’t feel this way. You can't convince a fool against his will . . . If a man doesn't like me because I'm black, that's fine. I'll just go elsewhere, but I'm not going to let him change my life.”

In 1954, his first full year and official rookie season, Banks finished second in the National League’s voting for rookie of the year. He won the Most Valuable Player award in 1958 and 1959, becoming the first NL player to win the award in back-to-back seasons. As shortstop, he led the league in fielding percentage three times. In 1960, he became the first Cubs player to be awarded a Gold Glove, and he led the league in fielding percentage, double plays, put-outs, and assists. His double-play partner was Gene Baker, another Negro League veteran. When Steve Bilko joined the Cubs at first base, Wrigley Field announcer Bert Wilson delighted in labeling the double-play combination, “Bingo to Bango to Bilko.”

A knee injury forced Banks to sit for a few games in 1961, after playing 717 consecutive games. When he returned, he was sent to left field, where he committed just one error in 23 games. In June, he moved to first base, where he played until he retired ten years later. He played more than a thousand games in each position—1,125 at shortstop and 1,259 at first, though he is best remembered for his years as a quick, agile shortstop.

Banks also was one of his era’s most prodigious sluggers. He retired after the 1971 season, finishing his career with 512 home runs and a lifetime batting average of .274. The 277 home runs he hit as a shortstop set an MLB record later broken by Cal Ripken. He also had 1,636 RBI and 2,583 hits, and he holds Cubs records for games played (2,528) and total bases (4,706). He also played a record 2,528 games without reaching the postseason. Despite the team’s failings, Chicagoans love their Cubs, and in 1969, readers of the Chicago Sun-Times named Banks the “Greatest Cub Ever.” Banks returned the favor by repeatedly expressing his pride in having played his entire major-league career with one team and for the same owners, the Wrigley family.

In his later seasons, when Banks suffered batting slumps, Cubs manager Leo Durocher complained that he couldn’t remove Banks from the lineup because he was too popular: “I had to play him,” Durocher said. “Had to play the man or there would have been a revolution in the street.” For his part, Banks thanked Durocher profusely for his coaching. In the later years of his career, as more African-American players joined the league and the Cubs, Banks became somewhat more vocal about injustice, though he always insisted he was there for baseball, not politics. He was also a lifelong Republican who supported Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Heavily Democratic Chicago forgave him.

Banks was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, his first year of eligibility, and his number 14 was the first number retired by the Cubs. Banks was named a Library of Congress Living Legend, a designation that recognizes those "who have made significant contributions to America's diverse cultural, scientific and social heritage." In 2013, another adopted Chicagoan, President Barack Obama, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, along with 15 other recipients including Bill Clinton and Oprah Winfrey.

Banks died on January 23, 2015. Following a public visitation, a memorial service was held at the Fourth Presbyterian Church in downtown Chicago. After the service, a procession moved from the church to Wrigley Field, Banks’ major league home from 1953 to 1971. The Friendly Confines welcomed home the franchise’s greatest ambassador.

This article was excerpted from Game Worn: Baseball Treasures from the Game’s Greatest Heroes and Moments by Stephen Wong and Dave Grob, Smithsonian Books, 2016