The Ill-Fated History of the Jet Pack

The space-age invention still takes our imaginations on our wild ride

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/ae/0dae914d-7b47-447b-bfdb-77ae93db34b9/jun2015_b01_nationaltreausre.jpg)

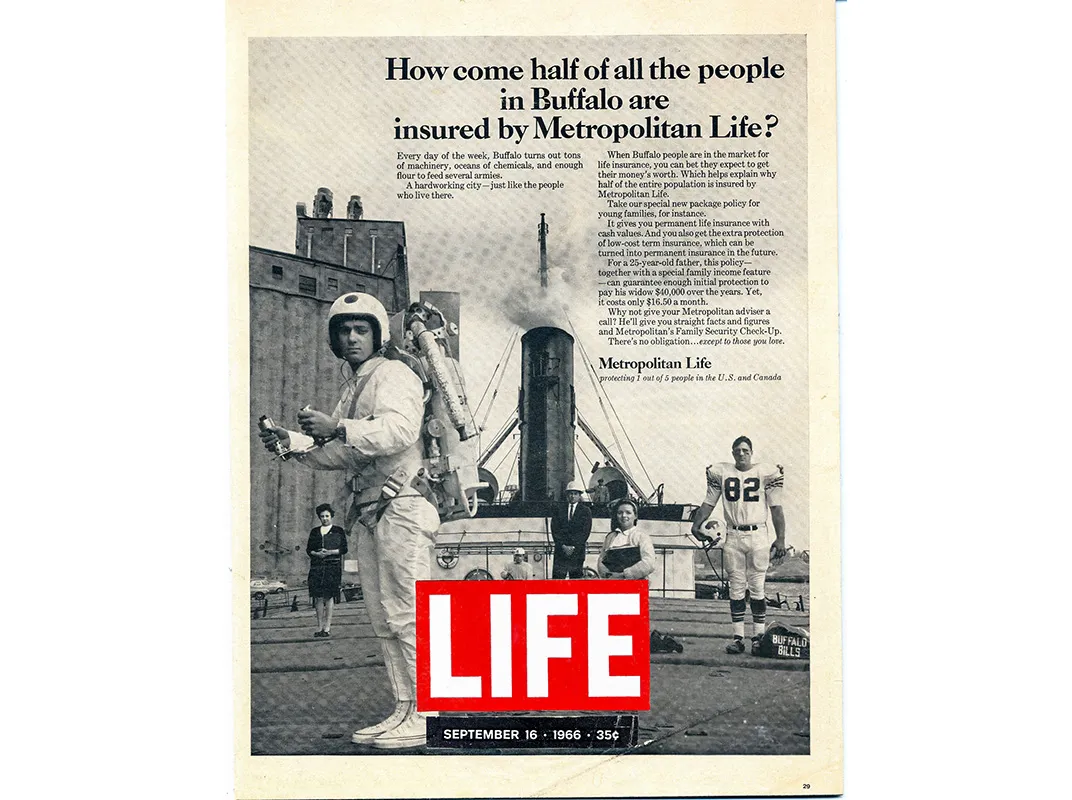

First we tried feathers and wax. Then Leonardo specified linen and wood. No matter the mythology or the machinery, the dream has always been the same: We’re flying. Floating over fields and cities, unstuck, untroubled, cut loose from the dust. The same dream again and again since we came out of the caves, right through Daedalus and Icarus to Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. This Bell Aerospace rocket belt is the dream made real—albeit updated by science and science fiction.

By the late 1950s, Wendell F. Moore of Bell Aerosystems, one of the great crew-cut, pocket-protected engineers at one of the great aviation companies of the postwar jet age, went to the drawing board and came back with the SRLD, the Small Rocket Lift Device, a Commando Cody-style backpack that could carry a single soldier into battle.

But only if that battle was about a block away.

The limiting factor for every rocket belt is the fuel load. Enough fuel to carry a flier for more than 20 seconds or so was too heavy to lift. That the SRLD worked at all was an engineering triumph. It could fly, hover, turn, go high or low, but could travel only short distances. Still, it was beautiful. Recognizable by its polished fuel tanks and control arms, custom-machined valves and foil-wrapped exhaust nozzles, stainless hoses and fiberglass backboard, it looks like a hot-rod scuba rig. Today, the second one ever built resides in the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM).

It works by sending pressurized hydrogen peroxide through a decomposition catalyst—in this case a series of fine-meshed screens made of silver. The peroxide instantly expands into superheated steam, producing a few hundred pounds of thrust at the exhaust nozzles. These are controlled by the pilot’s hand grips. There’s no aerodynamic lift; the thing stays aloft through the physics of brute force. It has the glide angle of an Acme anvil.

By 1962 the Bell team had a patent, and a flying rocket belt. It flew in trials, in the Pentagon courtyard, in front of President Kennedy. But as soon as you took off, you had to find a place to land. And rocket belts are hard to build, maintain and control, expensive to fuel and relatively dangerous. As a practical matter, they’re a failure.

But oh man, what a ride! And, NASM curator Thomas Lassman points out, every failure is a kind of scientific necessity, leading away from what doesn’t work to what does. “I think there is much historic value in this artifact because it illustrates so clearly a technological dead end,” he told me, “and shows us how technological enthusiasm can fail to meet expectations. Such failures are frequent in technological innovation.”

So your commuter rocket belt isn’t around the corner. It was obsolete the day it came out of the shop. It’s also not really a belt, but a pack strapped on by a harness. “Rocket pack” would have been best, but somehow the shorthand term “belt” gained currency. Still, the device works—within strict limits— and it speaks to the age of space travel and to the Rocketeer in every one of us.

Every so often Bell rocket belts turn up in movies and on television. “Lost in Space,” for example, or “Gilligan’s Island.” The most memorable example likely being the very first, the 1965 James Bond thriller Thunderball.

Since then, the handful of packs ever built have made it into civilian hands and become air show mainstays and popular halftime attractions. The belt’s appearance at the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics remains its peak moment.

The crowd on its feet below you, roaring. Those awed and upturned faces! Imagine the fame, the glory, the money! So dreamers and shade tree engineers are crazy about these things.

Down in Houston in the mid-1990s, three schemers formed what they dubbed the American Rocket Belt Corporation. Brad Barker engineered it in Joe Wright’s workshop. Thomas “Larry” Stanley bankrolled it. They built a rocket belt that extended the time aloft from 20 seconds or so to around 30.

But the partnership came apart over money. The belt disappeared. Wright wound up murdered (the case remains unsolved). Barker was abducted by Stanley, who tried to force his hostage to reveal the rocket belt’s whereabouts. Stanley ended up in prison. No one has seen the device since 1995. The broad outlines of the dark tale are found in Pretty Bird, a regrettable 2008 movie starring Paul Giamatti.

Better to see the Bell rocket belt in the new traveling exhibition, Above and Beyond, opening at NASM in August. Because even in our jaded age, the jet pack still fires the imagination. It’s just one more future that never got here from the past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)