Impressionism Into Modernism: Crafting America’s Unique Style of Art

After the Civil War, Americans became more interested in European art—and creating a kind of art completely their own

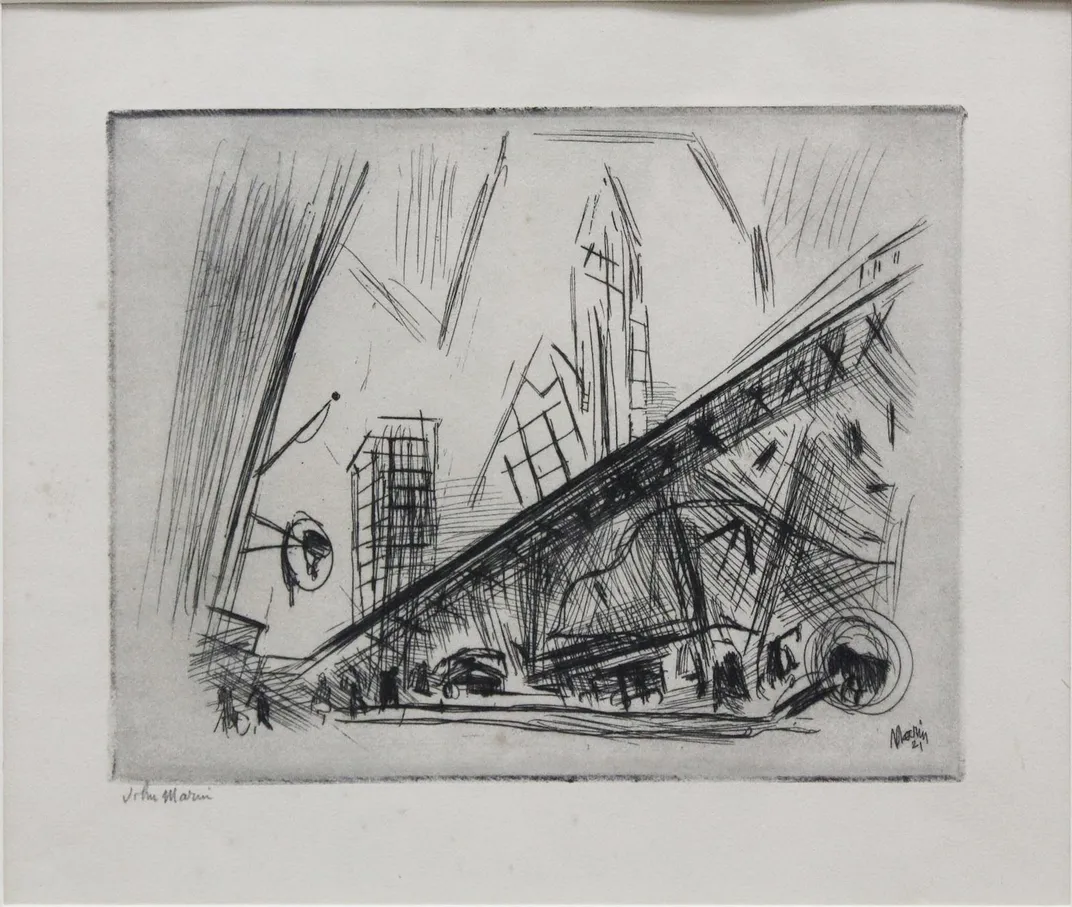

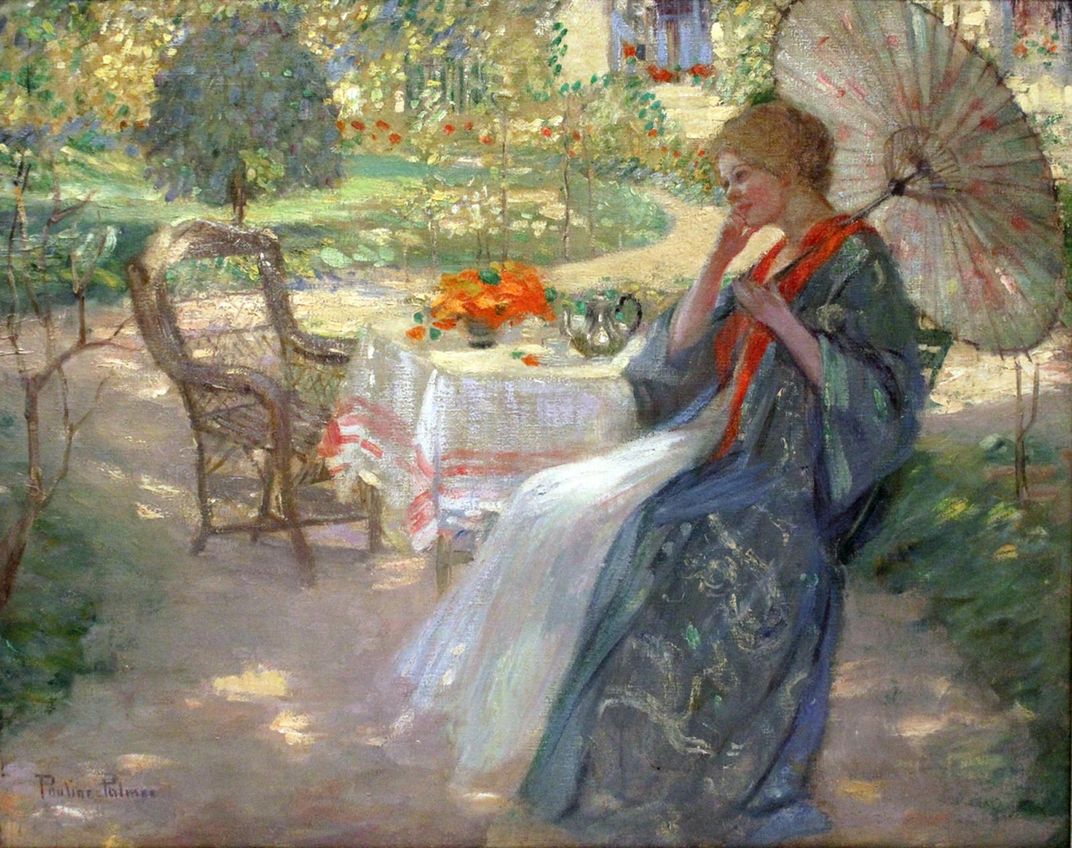

To be considered a serious artist in late-19th-century America, you had to have studied in a European, academic workshop, testing your brushtrokes among the masters of the continent. But art is nothing if not transformation, and almost as soon as American artists embraced the European traditions, they rebelled against it. Taking a cue from the French Impressionists who made their debut in their own private exhibition in 1874, these Americans grappled for a style that reflected the new realities of the post-war industrial American city.

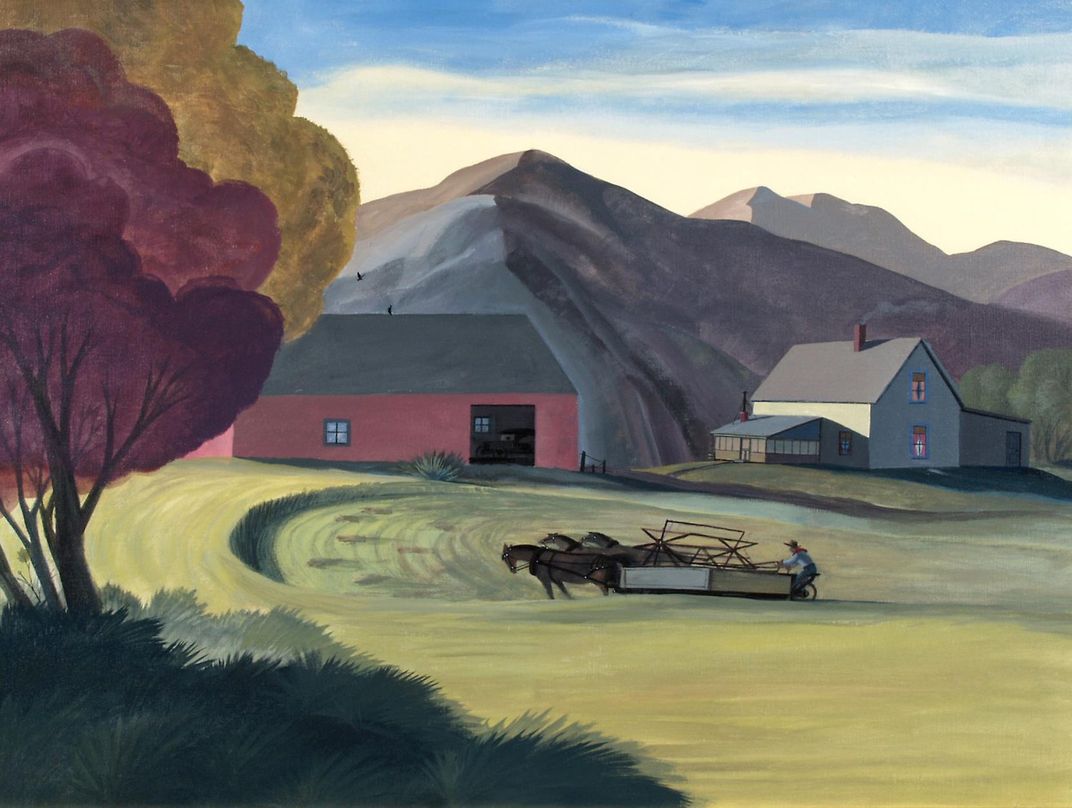

It is this journey—from the European tradition of impressionism to the avant-garde movement of Modernism—that will be on display at the Smithsonian Affiliate Peoria Riverfront Museum from September 26 through January 11, 2015. Featuring works spanning from the 1880s to 1950s, the exhibition "Impressionism Into Modernism: A Paradigm Shift in American Art," covers the Industrial Revolution, two world wars and a depression—all of which shaped the way American artists worked. "I felt that it would be interesting and appropriate to use American impressionism as a jumping off point as the story of the process of American artists embracing change," says Kristan McKinsey, the show's curator. "It's a time where American artists are moving away from academic art traditions and looking to create an art that was original and not derivative of European art."

The turn of the 20th century was a critical time for America's artistic identity, McKinsey explains. "We had skyscrapers and these amazing suspension bridges and jazz. Artists fled Europe during World War I, and while many went back, they'd had a taste of American culture," she says. America's urban modernity—its towering skyscapers and glistening bridges—helped Americans carve an identity unique from Europe, which was still regarded as the world's center of culture. But modernity truly came to America right before World War I, in 1913, with the opening of the famous Armory Show, its first appearance in New York City and its second stop in Chicago.

To many, the Armory Show marked the beginning of Modernism in America. It was the first time that the term "avant-garde" was used to describe art and sculpture, and many of the pieces on display represented styles the average American had never seen before. The show's European works shocked the American public, who viewed the experimental art (among the artists on display were Matisse, Van Gogh, Picasso, Duchamp and Gauguin) as grotesque. But the media backlash helped draw huge crowds to the show, which in turn exposed Americans to some of the less strictly academic work happening in Europe. One artist prominently featured in the exhibit is Manierre Dawson, a Chicago-born artist whose work was heavily inspired by what he saw at Chicago's iteration of the Armory Show.

To McKinsey, the Armory Show's appeal is local as well as historic, as the Peoria Riverfront Museum sits a mere three hours outside of Chicago. "Chicago was full of these artists who were at the forefront of Modernism, but perhaps just not as broadly known," she says. "This is an opportunity to celebrate Chicago's contributions to Modernism in America."

“Impressionism Into Modernism: A Paradigm Shift In American Art” is on view at the Peoria Riverfront Museum in Peoria, Illinois, from September 26 through January 11, 2015. Admission to the museum is free on Museum Day, September 27. Tickets are available here. Smithsonian Media's Museum Day Live! offers free admission to more than 1,000 museums across the country. Smithsonian Affiliations is a national outreach program that develops long-term, collaborative partnerships with museums, educational and cultural organizations to enrich communities with Smithsonian resources.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)