In a Historic First, a Large Collection of Islamic Qur’ans Travels to the U.S.

The art of the ancient Qur’an is showcased with the loan of some 48 manuscripts and folios from Istanbul, Turkey, and on view at the Smithsonian

Suleyman the Magnificent saw something he wanted. Within the Persian mausoleum of Sultan Uljaytu, a descendant of Ghengis Khan, was one of the most magnificently crafted copies of the Qur'an in the world. And what Suleyman wanted, he got.

The year was 1531 and Suleyman's army was rampaging across Persia as he solidified his status as the new leader of the Sunni Muslim world.

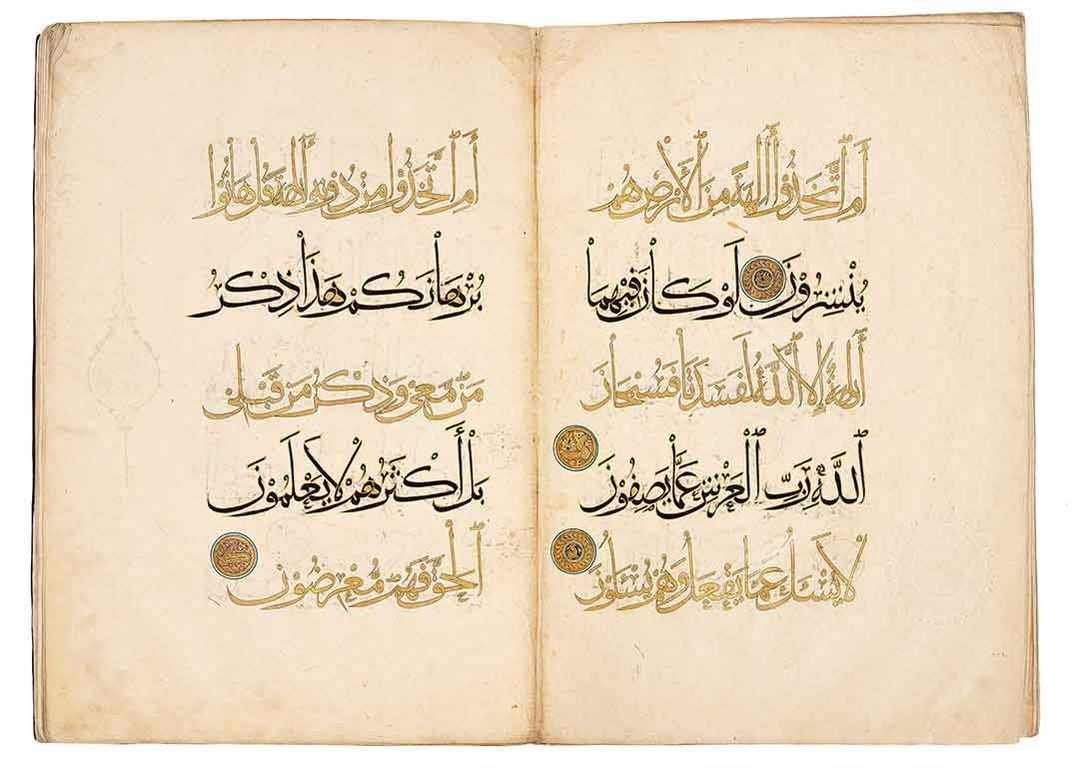

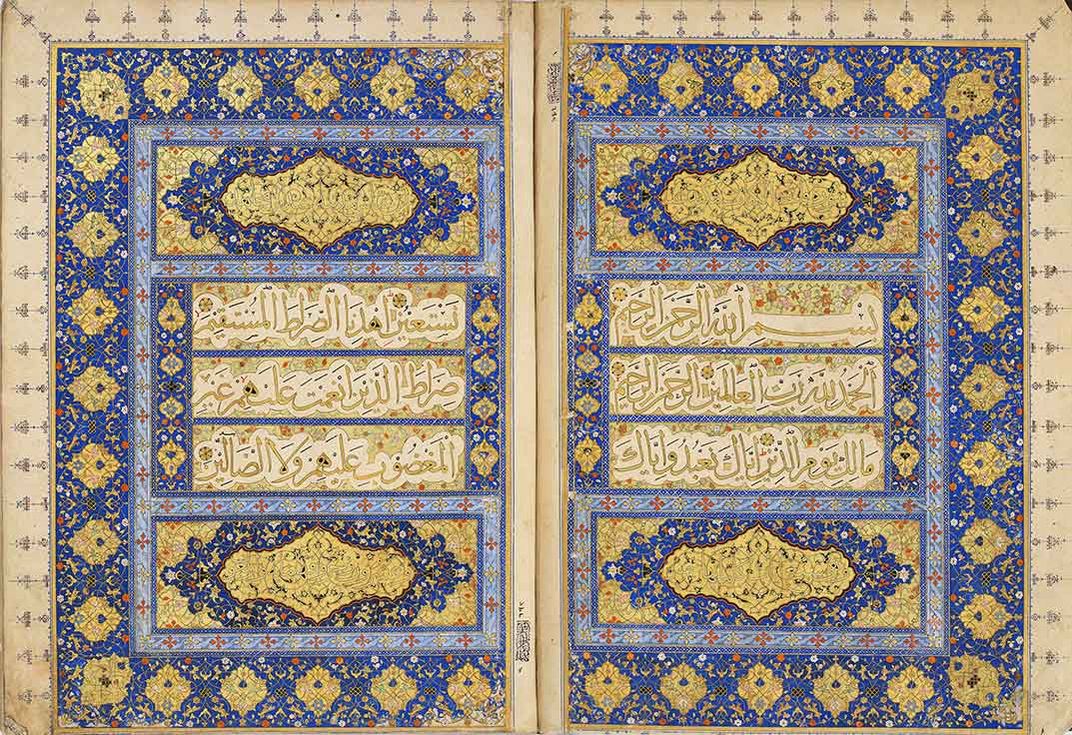

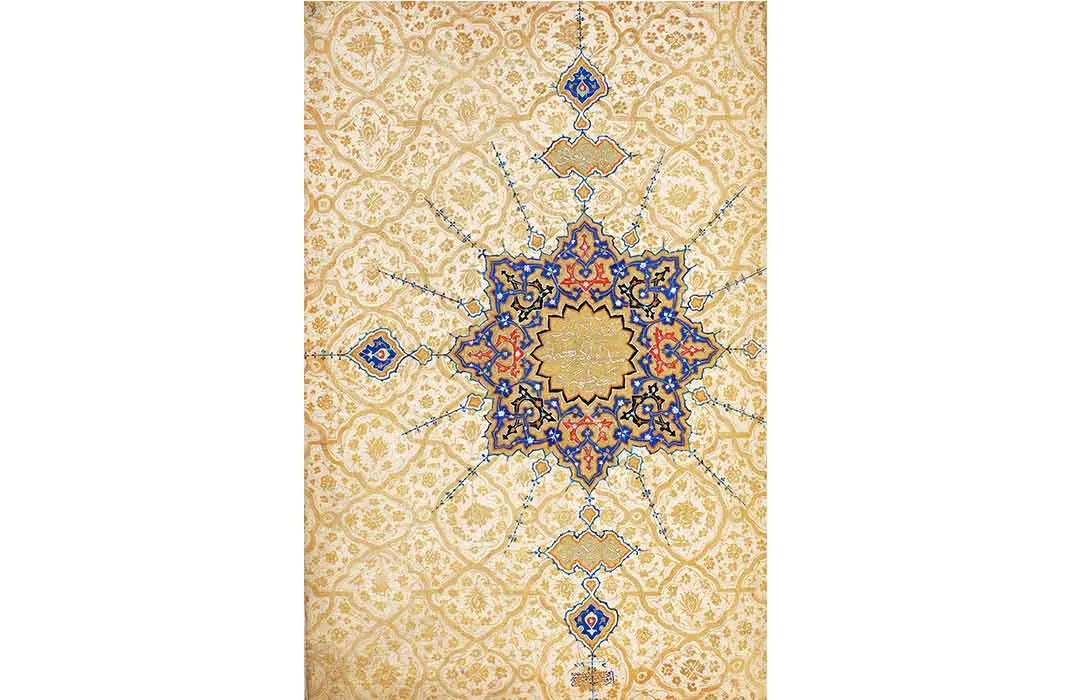

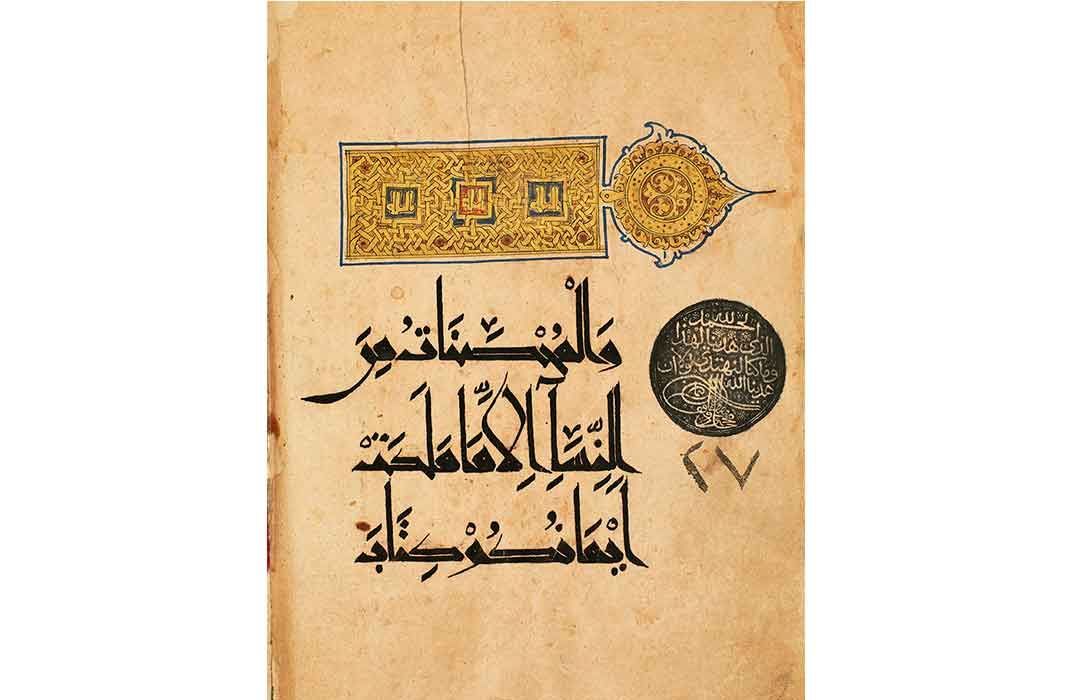

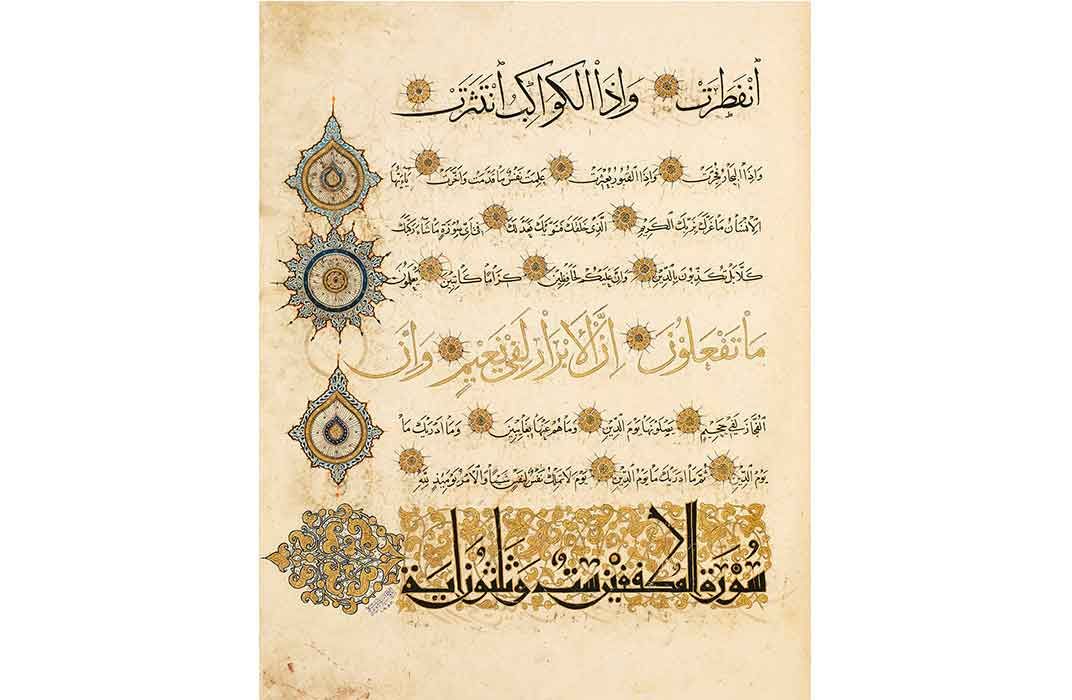

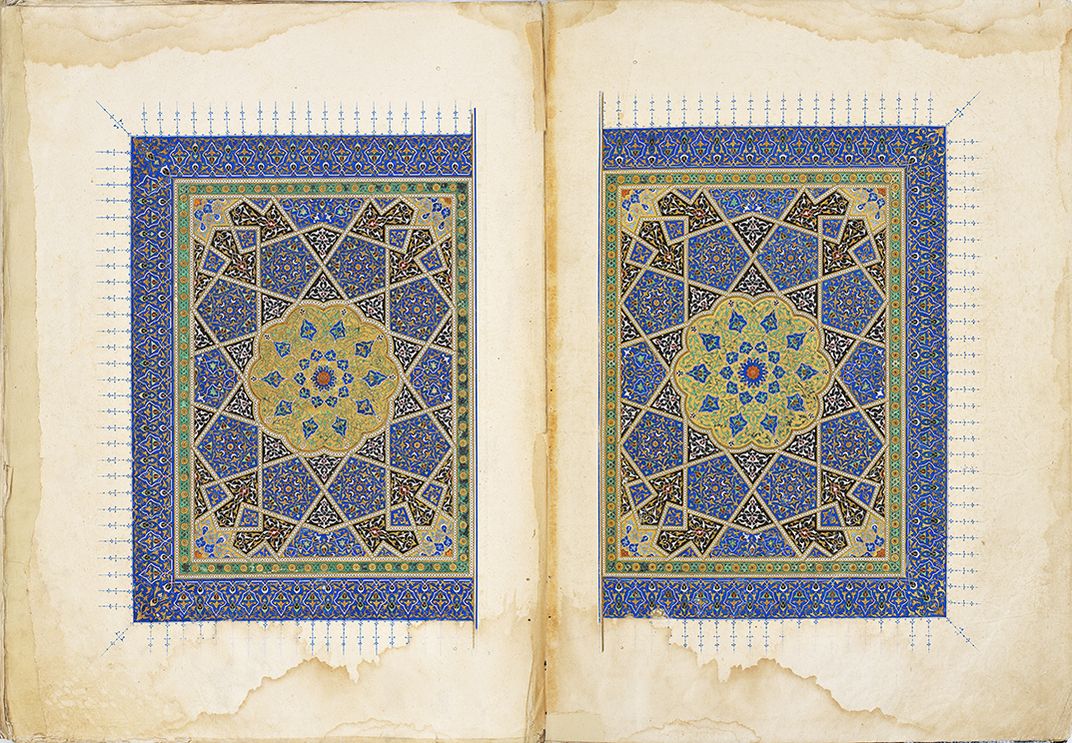

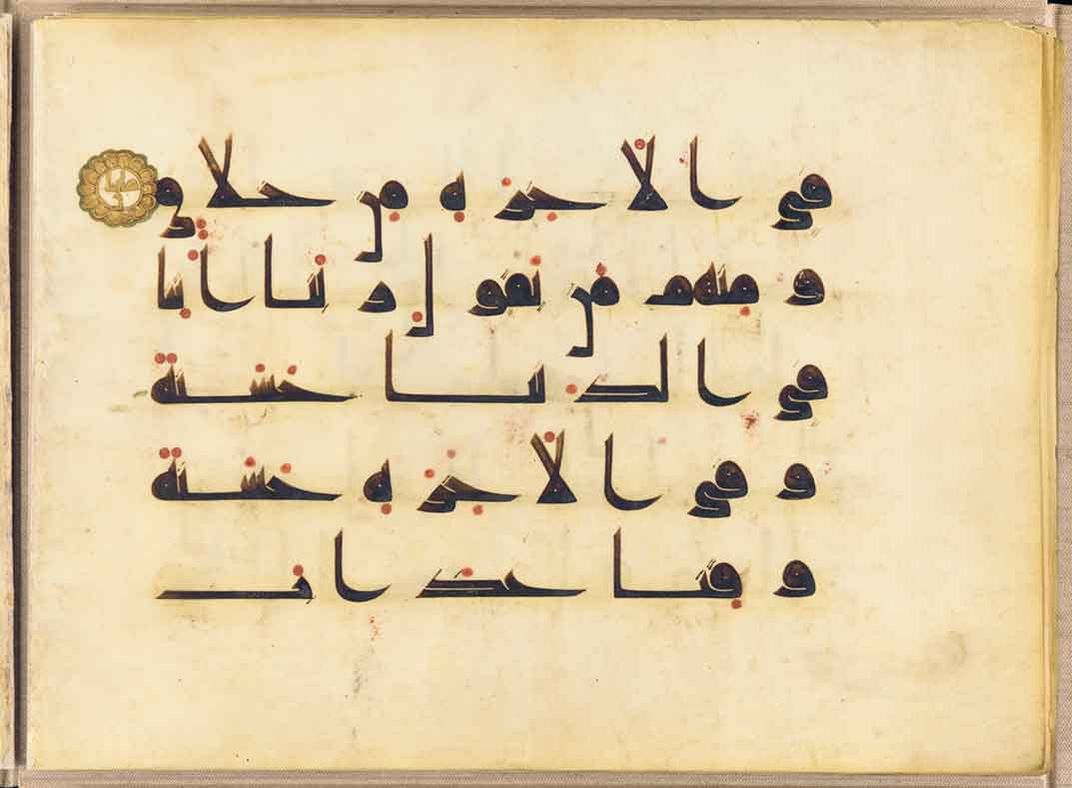

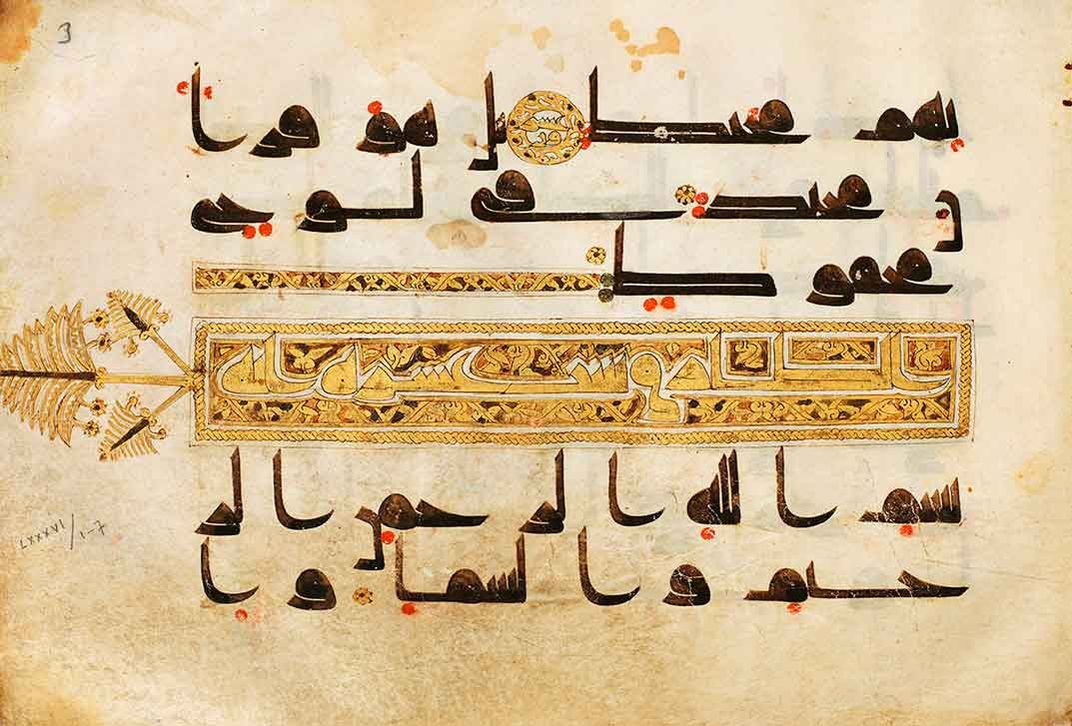

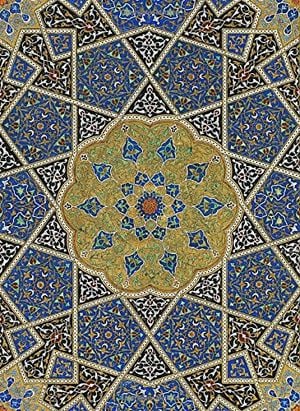

Accompanied by his Grand Vizier, Suleyman, with his enormous white turban blossoming over his head, stood before the mausoleum's magnificent dome. Underneath were vaults decorated in a riot of red, blue, yellow, green and white in patterns that were almost calligraphic. The Qur'an was displayed prominently on a specially made stand; this wasn't something that a visitor to the tomb could miss. Lines of gorgeous black and gold calligraphy seemed almost to float above the page. So what that it belonged to the tomb of Uljaytu?

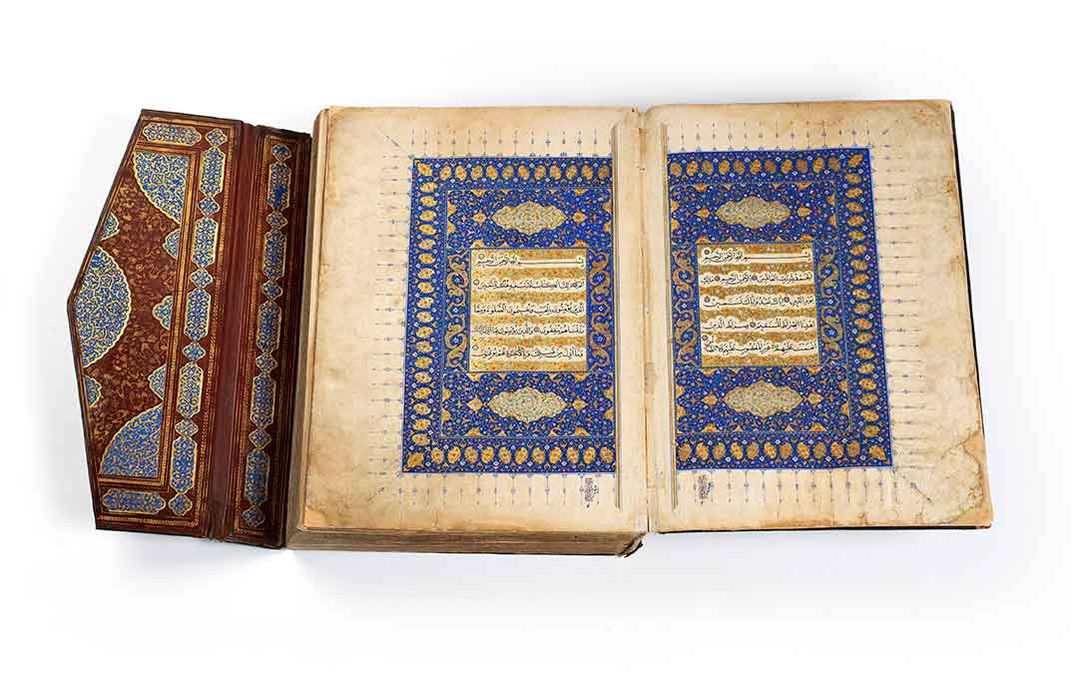

On October 22, that Qur'an will arrive at Smithsonian's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art as part of a collection of 68 of the finest examples of the art of the Qur'an ever to visit the United States. The exhibition will include 48 manuscripts and folios from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul dating from the eighth to the 17th-century, as well as several Qur'an boxes and stands and items from the museum's collections.

“This exhibition is really a sort of unprecedented opportunity to really see a different aspect of the Qur'an,” says Massumeh Farhad, the museum's chief curator and curator of Islamic art. “And really how incredibly beautiful these copies are.”

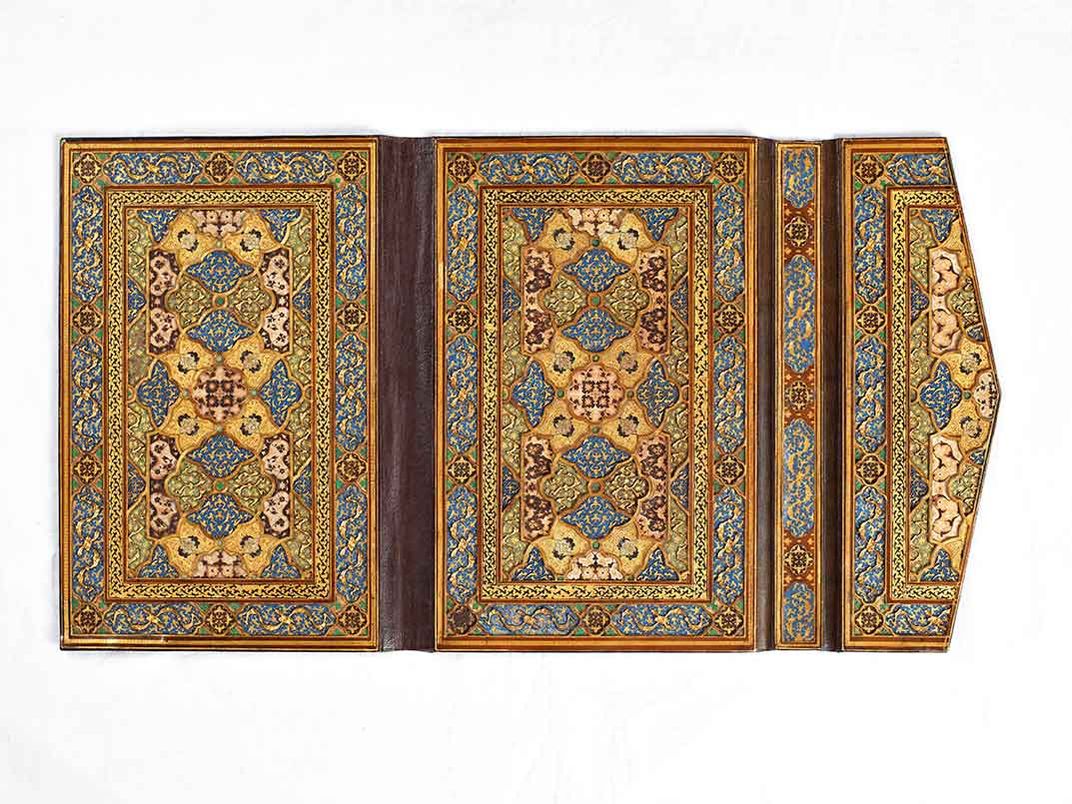

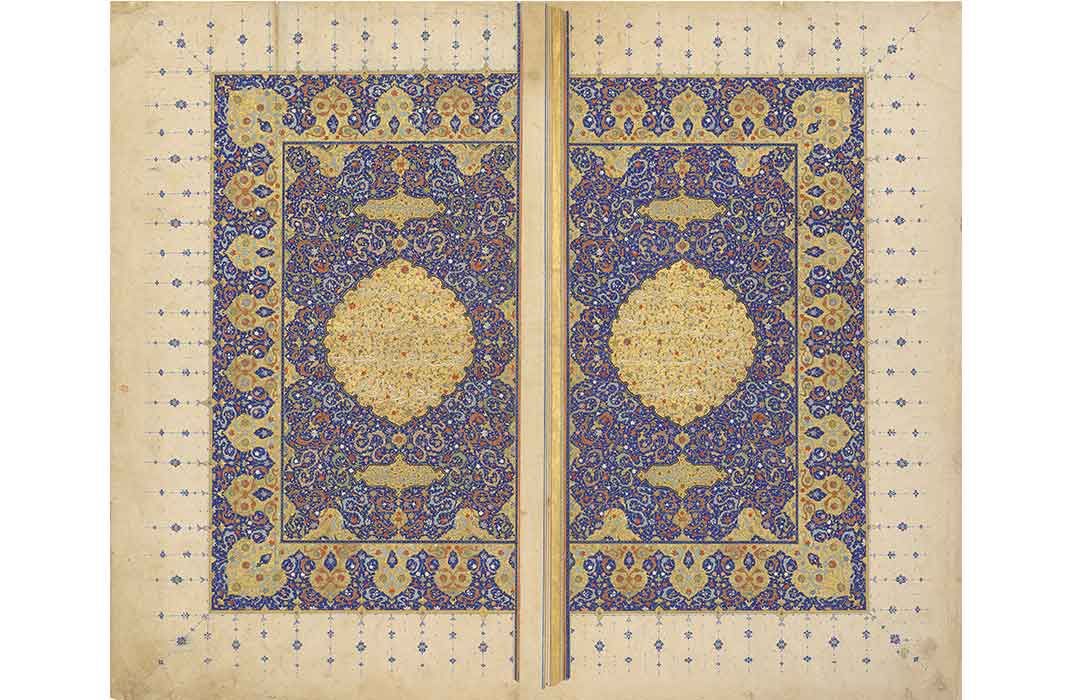

The Qur'ans on loan from Istanbul were the prized possessions of generations of Ottoman sultans and wealthy elites. Large, lavish, they were painstaking crafted to represent the word of God as well as to impress anyone who steps into the same room.

“What we have with this group of Qur'ans is that most of them were created for public display,” says Farhad. “They weren't shown quite the way that we display them in the museum. Many of them have notations saying that this manuscript was given to such-and-such institution, to be read out loud however many days a month. Others were given as gifts . . . you see their lavishness, their use of gold, and the size of them. Some of them were the size of a door. These were display pieces.”

“These were not mere copies of the Qur'an,” says Simon Rettig, the museum's assistant curator of Islamic art. “These were historical copies by great calligraphers. That would add sort of a special value to the object. They lended a political and religious legitimacy.”

Islam prohibits the artistic depiction of humans or animals, which redirected artistic talent towards other decorative arts, including calligraphy. In the centuries following the establishment of Islam, scripts became more and more elaborate. Illumination of texts spread, not entirely unlike the work of Christian monks in Europe and Britain. A graphic style evolved which permeated into other Islamic decorative arts and architecture, including the interior of the mausoleum of Sultan Uljaytu, where Suleyman walked off with the Qur'an that is now Rettig's favorite item in the exhibition.

“It was very much a form of diplomacy” says Farhad of the elaborate Qur'ans. “Whenever you went for negotiations, you brought all sorts of really precious things, material things, including Qur'ans. They were presented at public receptions. The first objects that were offered to the Sultan were usually Qur'ans.”

In that sense, the loan of these items from Turkey is in the finest tradition of illuminated Qur'ans. Although the loan took place as a result of Farhad's expression of interest rather than an initial offer from the Turks, it represents the public lending of important Qur'ans from the heirs of the Ottoman empire to their most powerful ally. This type of diplomacy has always been an important function of these objects.

The art of calligraphy is still thriving in the Middle East, but the availability of mass-produced books has contributed to a diminished role for the master Qur'an scribe. “Sort of the ultimate exercise you can do is copy a text of the Qur'an,” says Farhad. “There are still calligraphers who still do copies. But it's not done the way that it used to be earlier on.”

Every copy of the Qur'an in the exhibition has an identical text, executed completely differently and designed to strike the viewer with admiration and humility. “I remember when Simon and I had the privilege of being in the library at the museum in Istanbul,” recalls Farhad. “And we were allowed to leaf through them. It's sort of meditative. I'll never forget, there was one particular Qur'an I saw and I said if I'm hit by lighting now, it's fine!”

"The Art of the Qur'an: Treasures form the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts" opens October 22 at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art. The show will be on view through February 20, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)