Keep an Eye on These Portraits Because They Move

Noted visual artist Bill Viola is subject of the first all-video exhibition in one of D.C.’s oldest buildings.

“Watch,” says Bill Viola, staring intently at one of his works, which he knows as well as a recurrent dream. “See what happens.”

And while most of the artworks at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, from those of the presidents to those in the contemporary shows, are certainly worth a look, Viola’s body of work, entirely on video, requires a longer view—and watching.

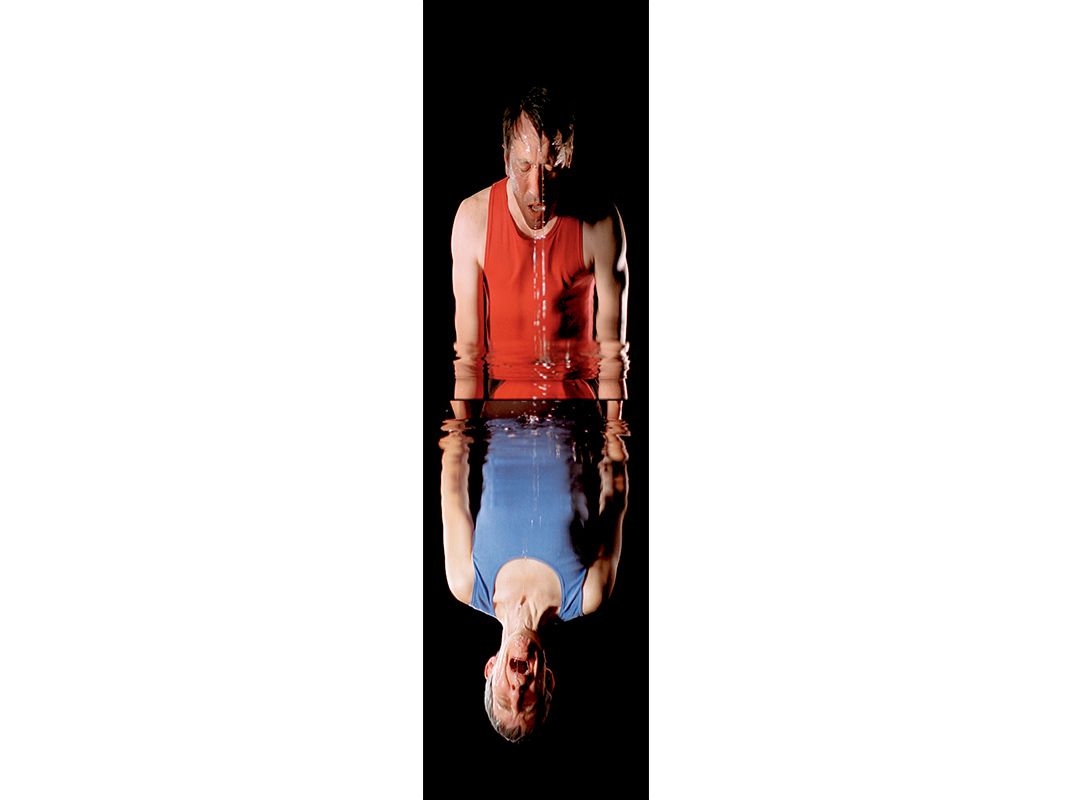

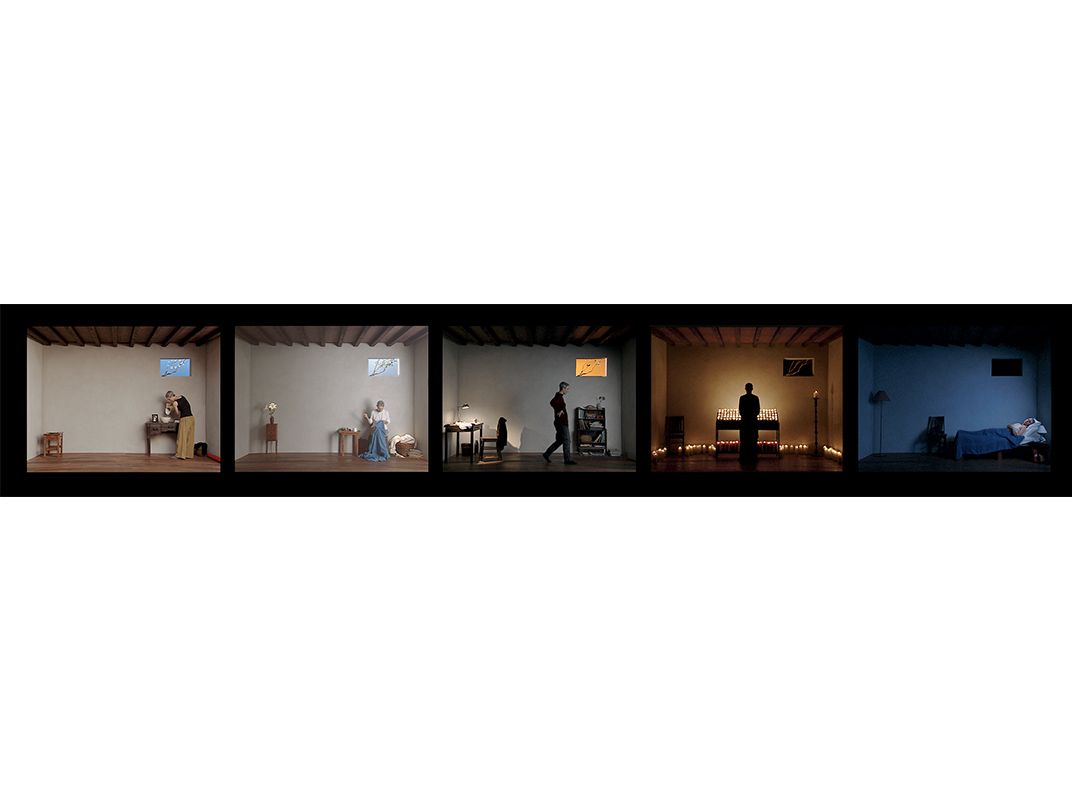

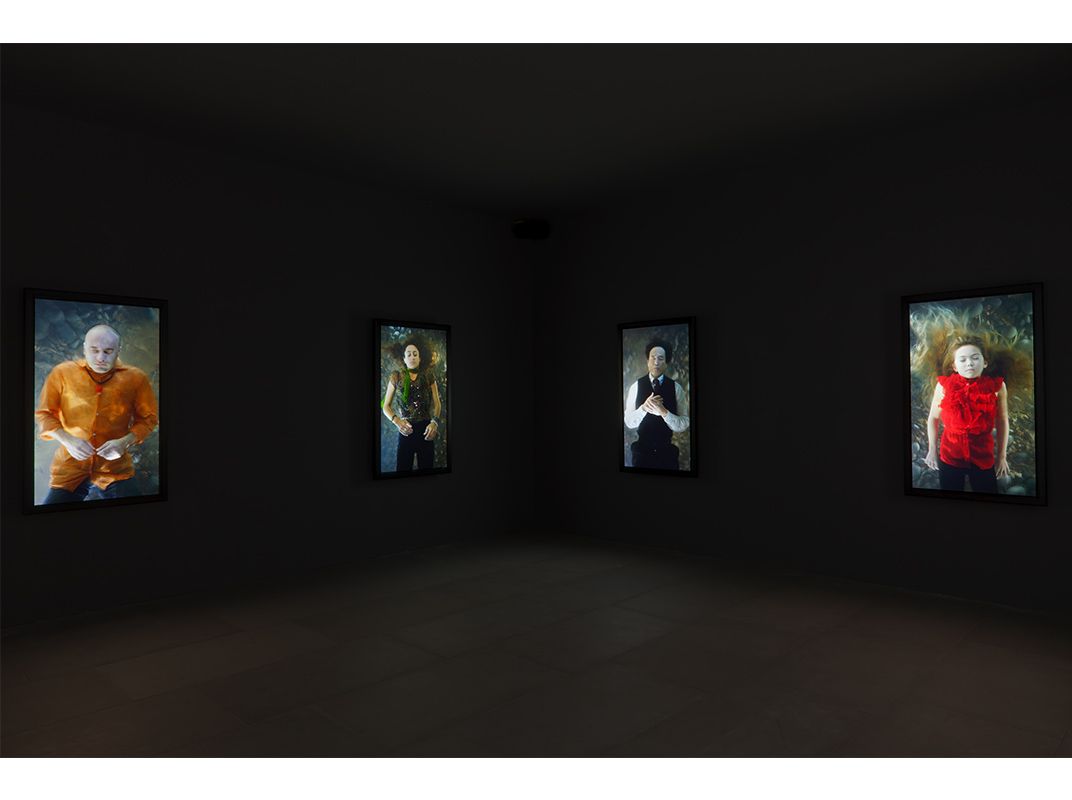

In the current retrospective at the Washington D.C. museum, “Bill Viola: The Moving Portrait,” subjects in the 11 media pieces often move slowly, sometimes imperceptibly, in their frames, seemingly contemplating their states of being or imagining a transfiguration, in spirit if not flesh, by often using water.

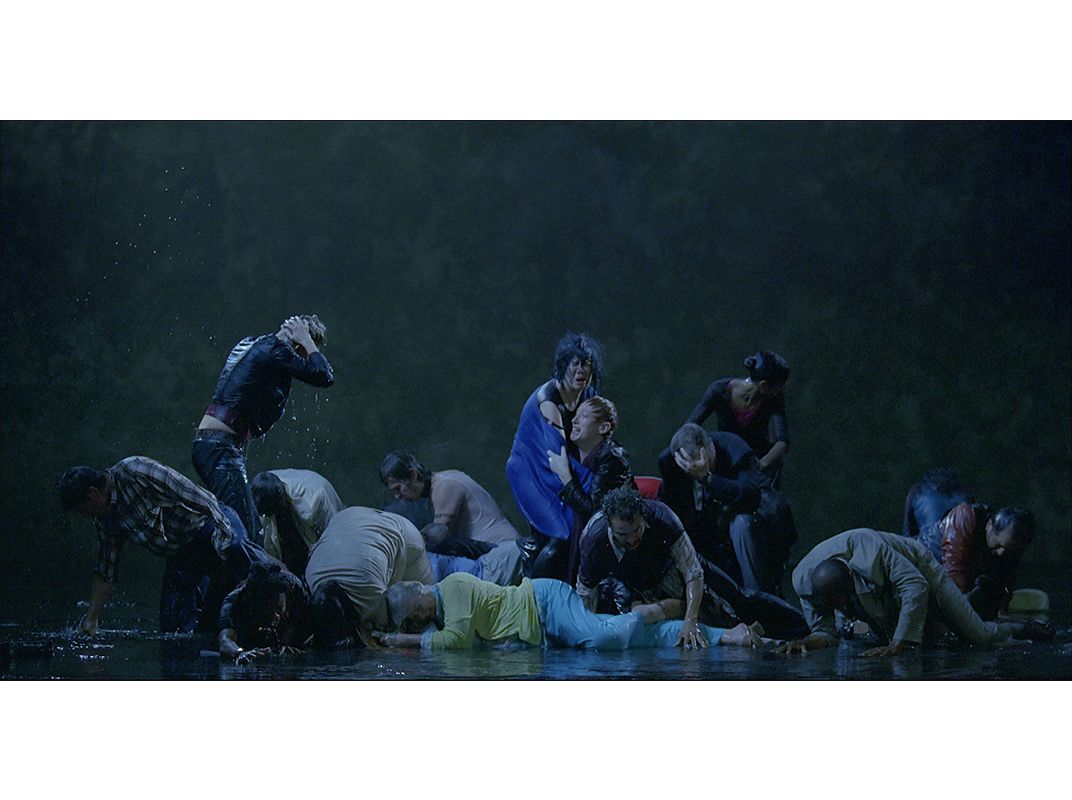

In the show’s most spectacular piece, the 2004 The Raft, a group of people seemingly awaiting a bus are hit instead with a blast of water that knocks them down—in dramatic slow motion, a metaphor for group response, perhaps, to sudden tragedy.

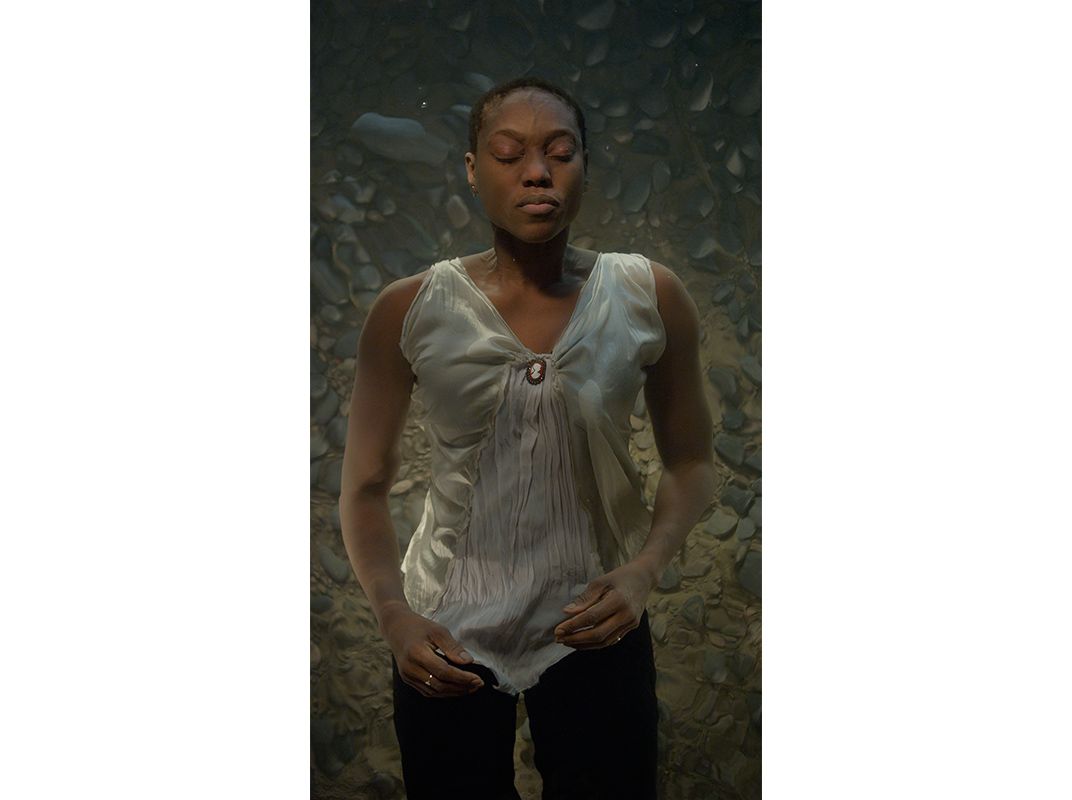

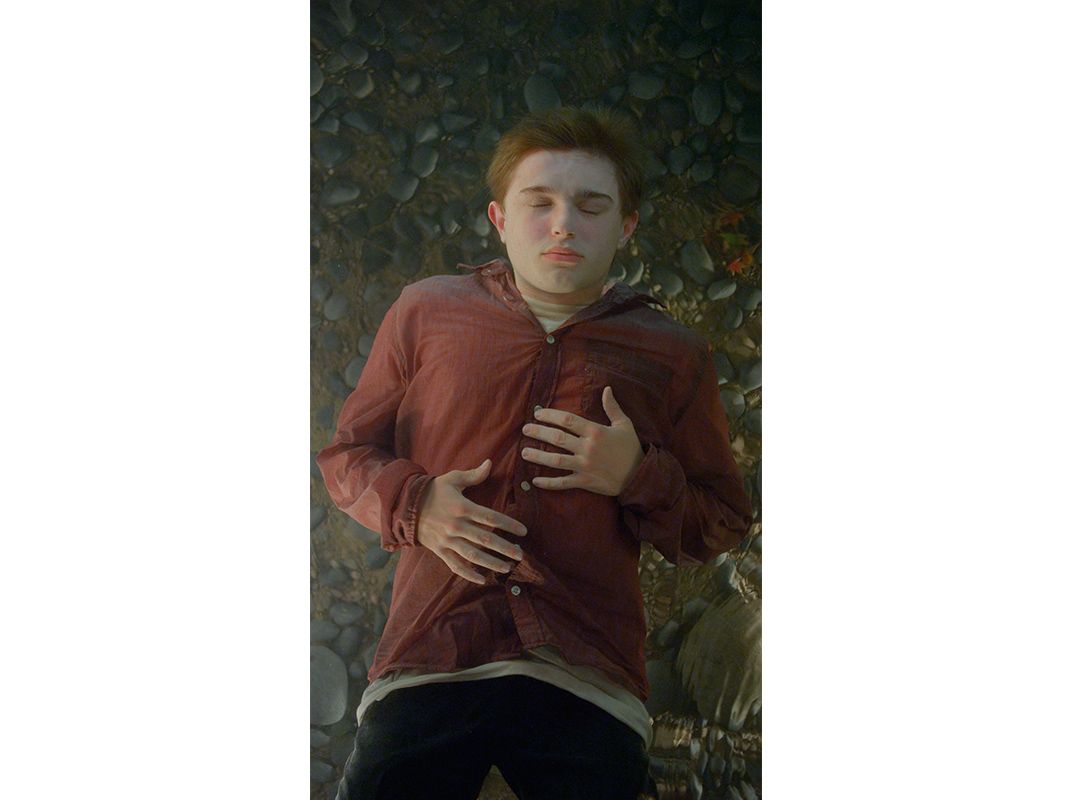

In another, a masterful grouping of seven clothed lifesized figures, The Dreamers from 2013, are lying submerged in shallow water, as if awaiting ascension or some other transmogrification.

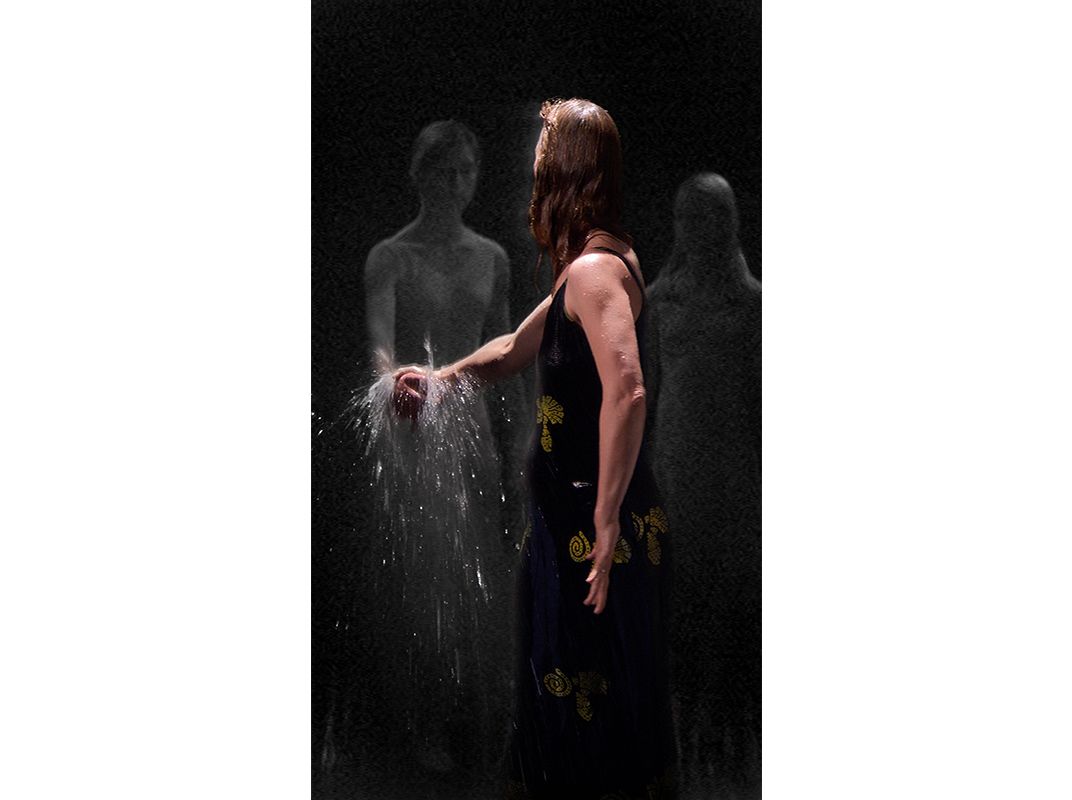

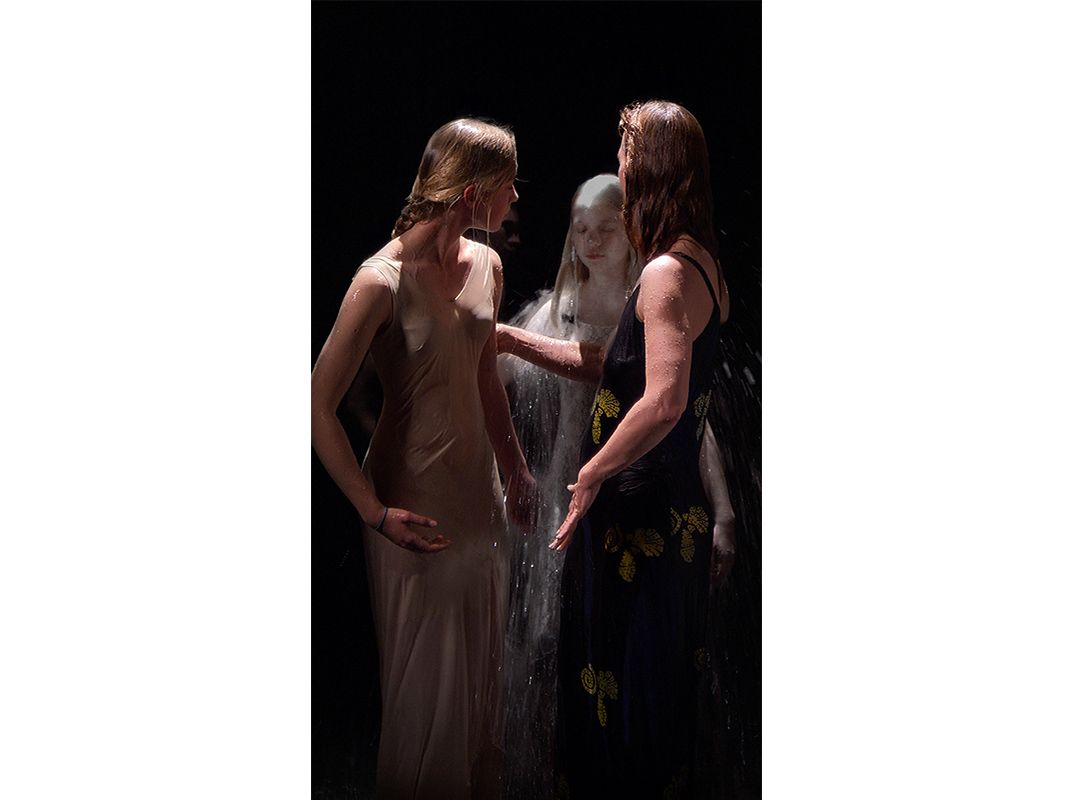

But here, Viola, 65, is considering the women and daughters moving from one side of a sheet of water to another in the 2008 work Three Women. On one side, their figures are grainy transmissions from a security camera; on the other, they are drenched in color and high resolution (as well as by water).

“You’ll see what happens,” Viola says, as the nine-minute piece continues.

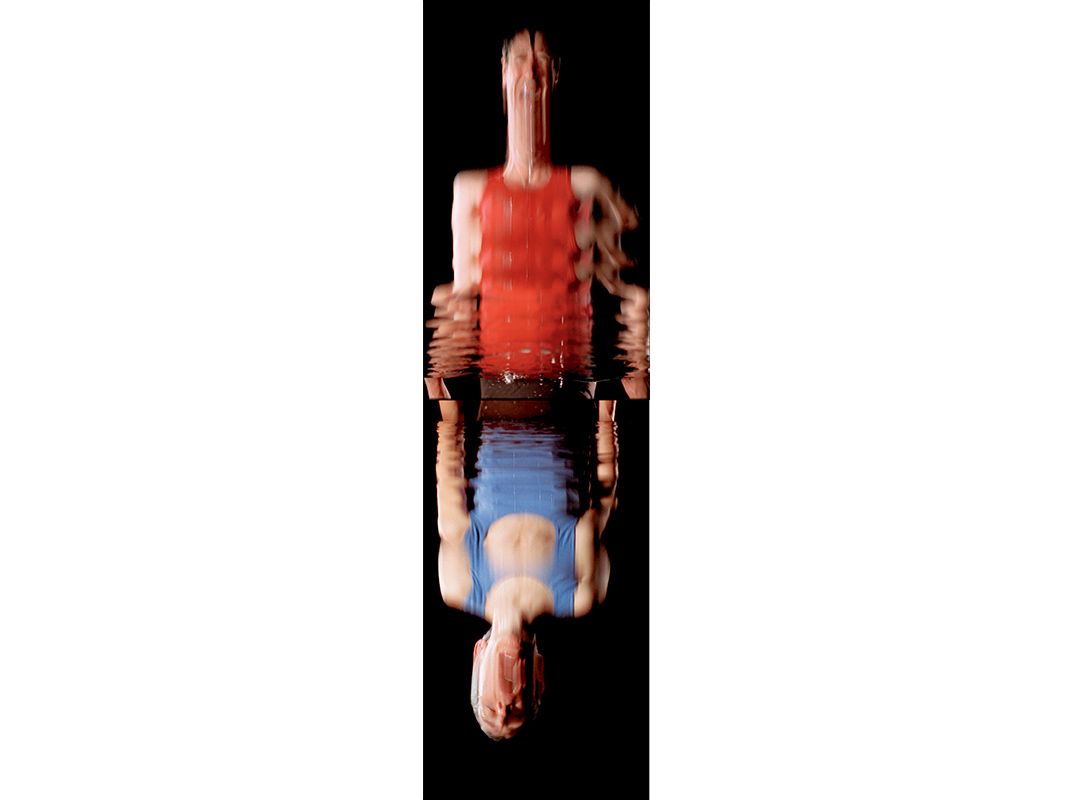

Viola’s work in video began almost as soon as commercial handheld cameras became available in the marketplace in the early 1970s. It was there that he shot one of the earliest works in the survey, The Reflecting Pool, in which the artist appears, jumps in the water, hangs in the air, and seemingly disappears before he lands.

“Time,” he says in a statement, “becomes extended and punctuated by a series of events seen only as reflections in the water.”

“Bill’s been using water for a long long time,” says Kira Perov, Viola’s longtime creative partner, also taking another look at the watery curtain of Three Women. “This piece is part of what’s called the transfigurations series. He was using it as a threshold between life and death. Which is a threshold and he’s used that a lot in the past.”

It dates back to a childhood near-tragedy. “Bill had an experience when he was quite young where he nearly drowned,” Perov says.

“That’s where it started,” Viola says.

Since then, it’s appeared in many of his pieces that have been displayed all over the world, such as the Durham Cathedral in England. One of his most recent works was installed at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

The elemental quality of his work certainly speaks to wide audiences. But did he ever consider his work portraiture?

“That’s a very interesting question,” Viola says.

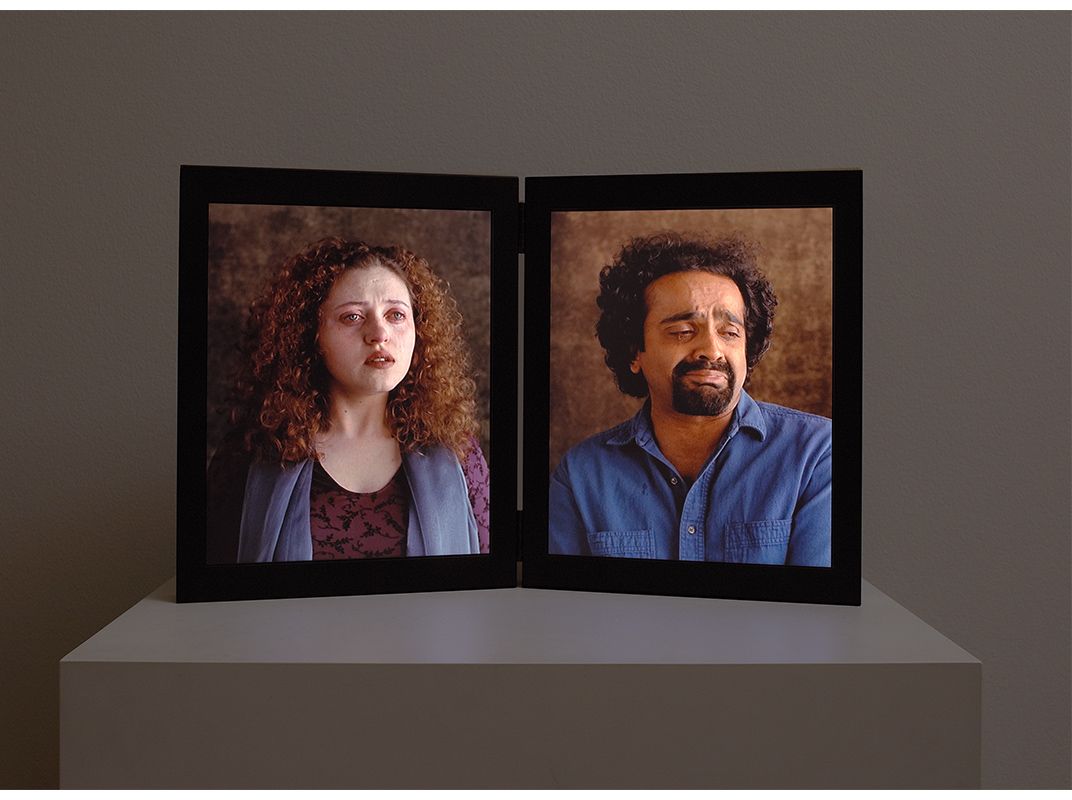

“We never really talked about portraits,” adds Perov. “We talked about emotions.”

And yet, according to Asma Naeem, the museum’s curator of prints who also curated the Viola show, “The Dreamers is a water portrait series, and you have a work that’s a self portrait.”

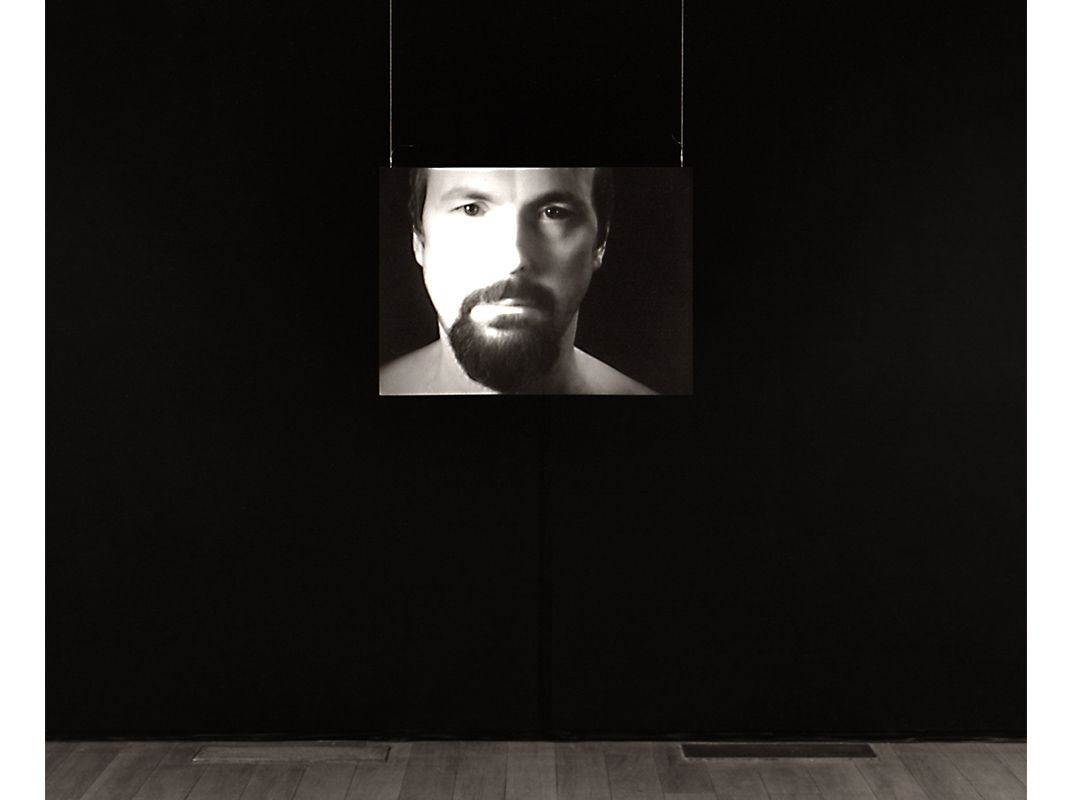

The 2013 Self Portrait, Submerged is not formally part of the show, but a recent acquisition to the Portrait Gallery and sits on the main floor as if to beckon viewers into the nearby elevators to visit the show.

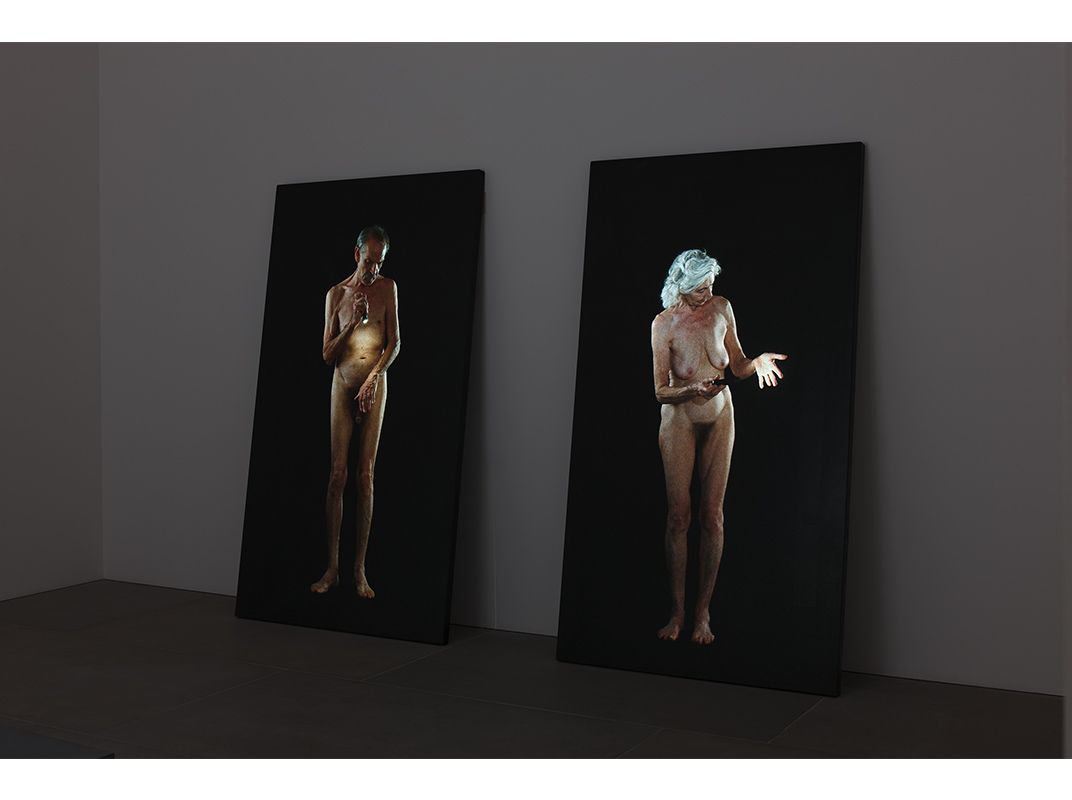

Figures are part of most of the survey’s pieces, from the barely moving faces of the 2000 Dolorosa, the deceptive reflections of the 2001 Surrender and the stark elderly figures of Man Searching for Immortality / Woman Searching for Eternity from 2013, that seems to glow from its projection onto nine foot slabs of black granite.

“But it’s this idea of a more metaphorical idea of portraiture that we’re trying to push, beyond this idea of likeness,” Naeem says.

“And especially because it’s moving,” Perov says, “it’s a moving image that can develop into other observations of life.”

While there have been other video works in the collection (about 17 of them), “Bill Viola: The Moving Portrait” is the first Portrait Gallery show completely devoted to video technology—no mean feat for a building that was built before electricity.

“What it took to provide the infrastructure—the behind the curtain part of this—is kind of staggering,” says Alex Cooper, the museum’s exhibits production manager. Plans for infrastructure changes began to be drawn more than 16 months ago and installation took three months, Cooper said, “in an effort to make the work appear as minimalist as it is.”

It’s all an achievement for a federal structure that began construction in 1836, which served as patent office, Civil War barracks and site of a Lincoln inaugural ball, among other things. “We’re doing cutting edge 21st century art in one of the oldest buildings of the city,” Cooper says. “It’s so interesting when you think about that.”

“The great thing is the ceiling heights,” says Perov. “We’re usually restricted by the ceiling heights. That’s a very big problem for us. But of course this is a portrait show, so it’s a different for us. We deliberately selected works that would fit.”

The result is a cool, crisp and quietly moving exhibition that Naeem says hopes to draw younger people. “Kids are going to be wow, for anything on screens,” she says.

Viola too seemed pleased to see his work in a different context as well. “It’s an amazing thing to take what you have and move things around and get them where we want to place them.”

“Bill Viola: The Moving Portrait” continues through May 7 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)