Long Before Emojis, the Picassos of Persian Calligraphy Brought Emotion to Writing

The world’s first exhibition devoted to nasta’liq, a Persian calligraphy, is now on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

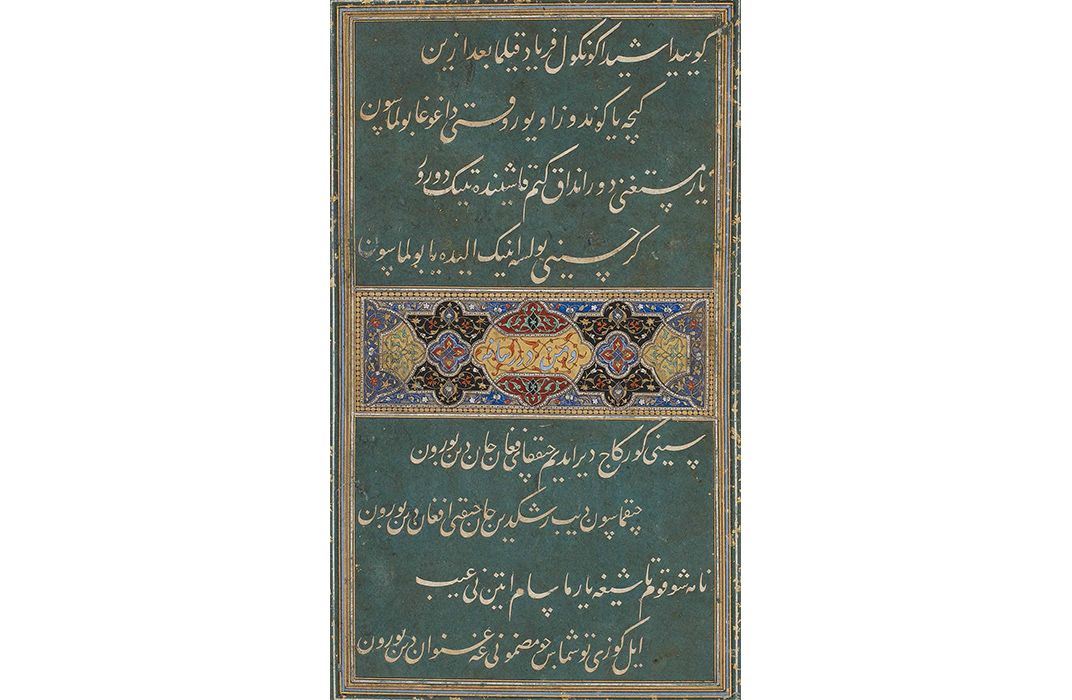

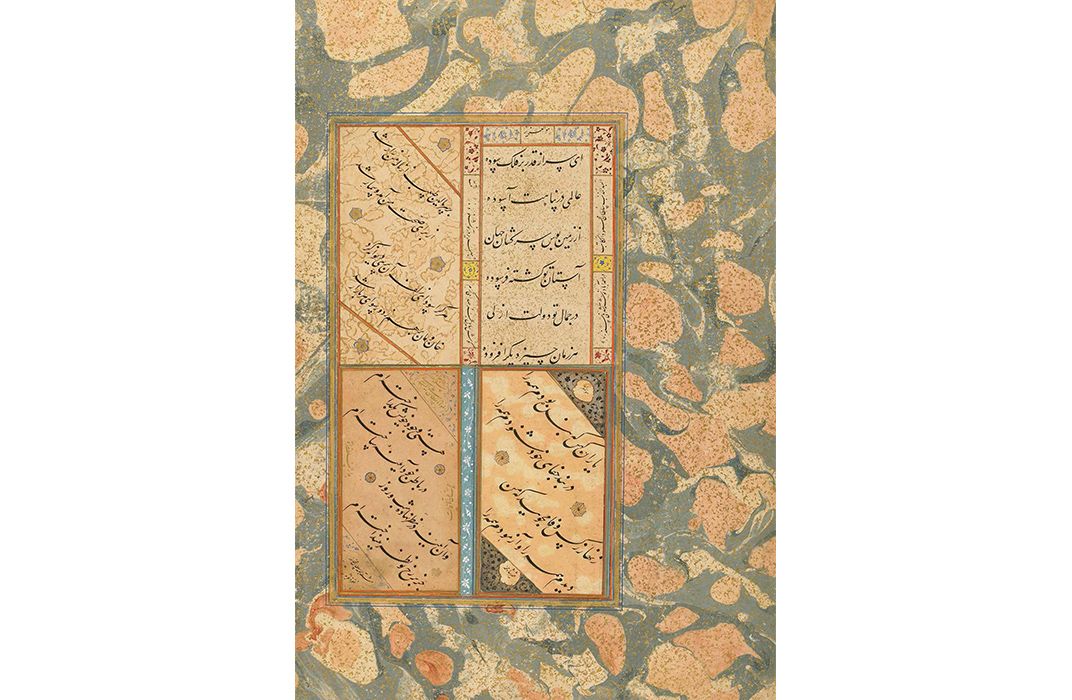

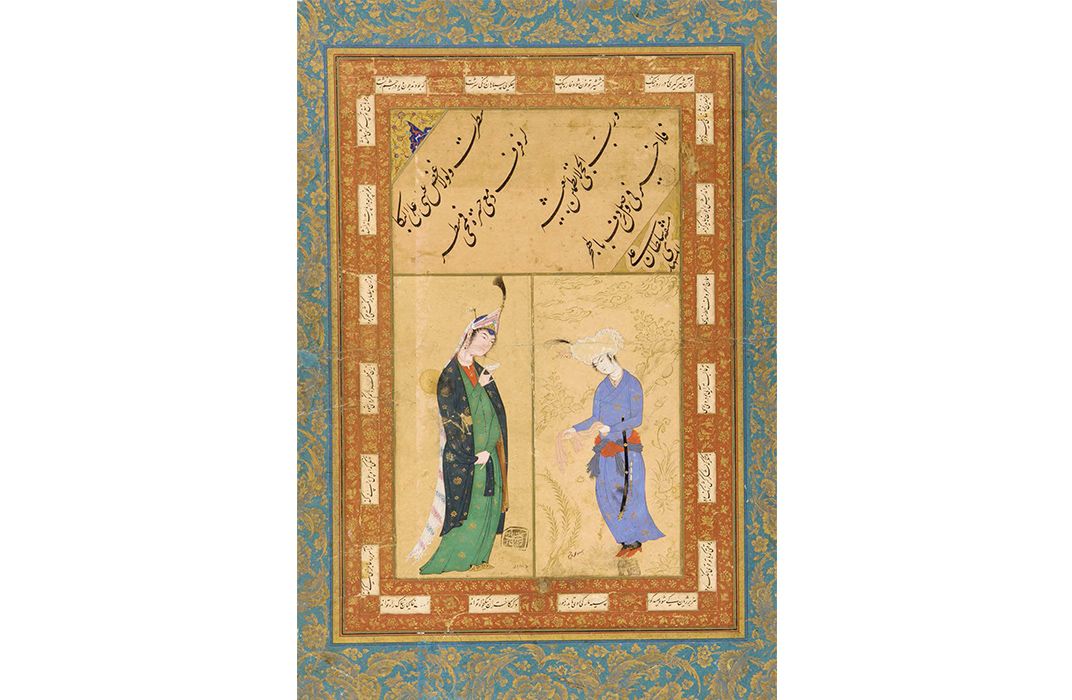

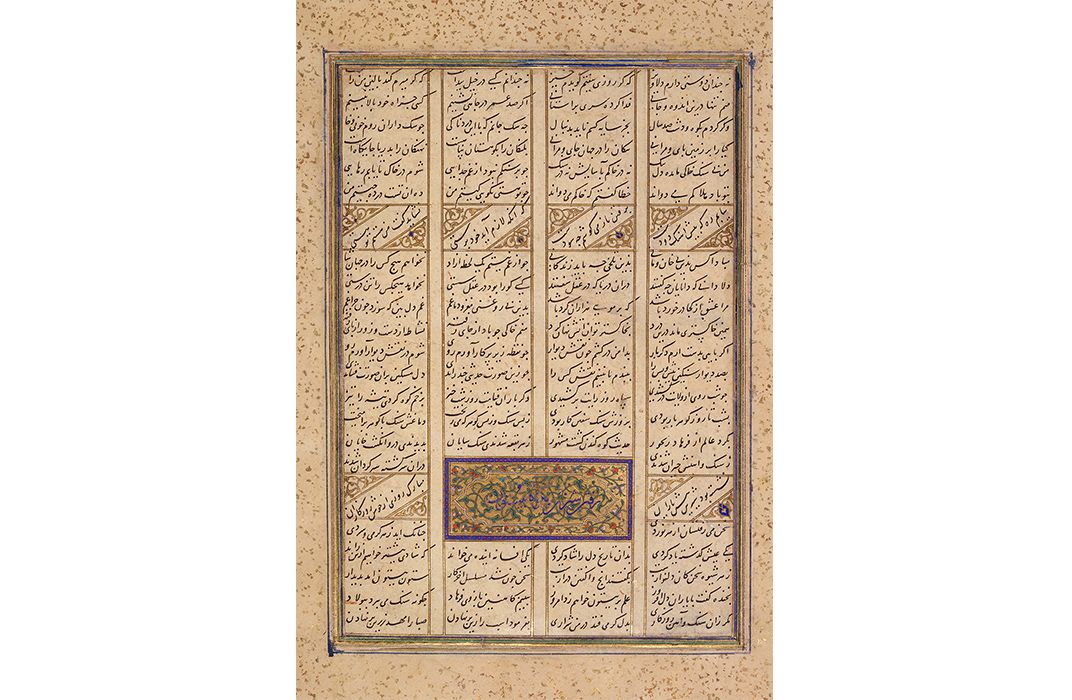

Six hundred years ago, a Persian prince would have sat down in his palace and leisurely perused a book of poetry. The lines would have been penned in a highly stylized calligraphy called nasta’liq and mounted inside gold borders and alongside elaborate illustrations. The poetry would have come from ancient texts or may have been written by the prince himself.

Now visitors can play Persian prince at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, where the world’s first exhibition devoted to the artform and entitled “Nasta’liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy” opened on September 13. At a time when writing with pen and paper is in decline and more often quick, electronic and ephemeral—or in the case of text message emojis, without any words at all—ancient calligraphy is a reminder of the aesthetic value of the written word.

“Nasta’liq is really the visual embodiment of the Persian language and still today it is the most revered form of calligraphy in Iran,” says Simon Rettig, curator of the exhibition. Iran was the center of Persian culture, which also expanded to Turkey, India, Iran, Iraq, Uzbekistan and elsewhere. The four calligraphers at the heart of the show—Mir Ali Tabrizi, Sultan Ali Mashhadi, Mir Ali Haravi and Mir Imad Hasani—were considered celebrities during the era. “These guys were the Leonardo da Vincis or the Picassos of their time,” Rettig says, adding that even today in Iran, their names remain well known.

Scholars consider Mir Ali Tabrizi (active circa 1370-1410) the inventor of nasta'liq. The style of writing developed in 14th-century Iran and peaked over the next two centuries. Previously, calligraphers had written the Persian language in the same scripts as the Arabic and Turkish languages, and so Mir Ali Tabrizi wanted to create a script specifically for Persian. “At some point there was a need for developing a script that would visually feel [the] language,” Rettig says, noting that there are no special scripts tied to any particular languages using the Latin alphabet.

Previous Islamic calligraphies existed primarily for religious purposes. “When we usually talk about calligraphy in Islam, we think about Koran and calligraphy with religious contexts. Nasta’liq is everything but that,” Rettig says. “Arabic was the language of religion in this part of the world and Persian was the language of culture.”

Composing nasta’liq was a unique skill passed from master to pupil. The calligraphers mixed their own ink using ingredients such as gum and gallnut (a growth on vegetation) and kept the recipes secret. “Do not spare labor in this. Know otherwise that your work has been in vain,” the calligrapher Sultan Ali Mashhadi instructed in 1514. Calligraphers compose nasta'liq slowly from right to left by twisting a sharpened reed or bamboo pen.

The cornerstone artifact in the exhibition is the only known manuscript signed by Mir Ali Tabrizi. All but two of the 32 works and artifacts on display were pulled from the permanent collections of the Freer and Sackler Galleries of Art. “Few collections in the world have the depth of the Freer and the Sackler in calligraphic pages in nasta’liq,” says Massumeh Farhad, chief curator and curator of Islamic art. “The script is remarkable for its subtle control and rhythmic beauty.”

“Nasta’liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy” is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery until March 22, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/52/2152a88a-4fd1-4f96-86da-f10fb6c9f548/border_illustration-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/6f/fc6f146c-806e-4854-a022-6ab8a2da9140/diagonal-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)