Meet the Makech, the Bedazzled Beetles Worn as Living Jewelry

The unusual bugs from the Yucatán have a backstory as colorful as their rhinestone-studded rumps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/2e/e72ee0bb-fe4a-4747-85c9-352d7ca5acb1/12dsc04975web.jpg)

In 2006, fashion designer Jared Gold grossed out fans of America's Next Top Model with his "roach brooches"—live hissing cockroaches decked out with crystals and sold as wearable jewelry for $60 to $80 a pop. To the best of his knowledge, the idea was totally unique: other cultures have used dead bugs as décor, but "as far as live insects go, we are Patient Zero," he said during a Washington Post online chat about the creepy-crawly baubles.

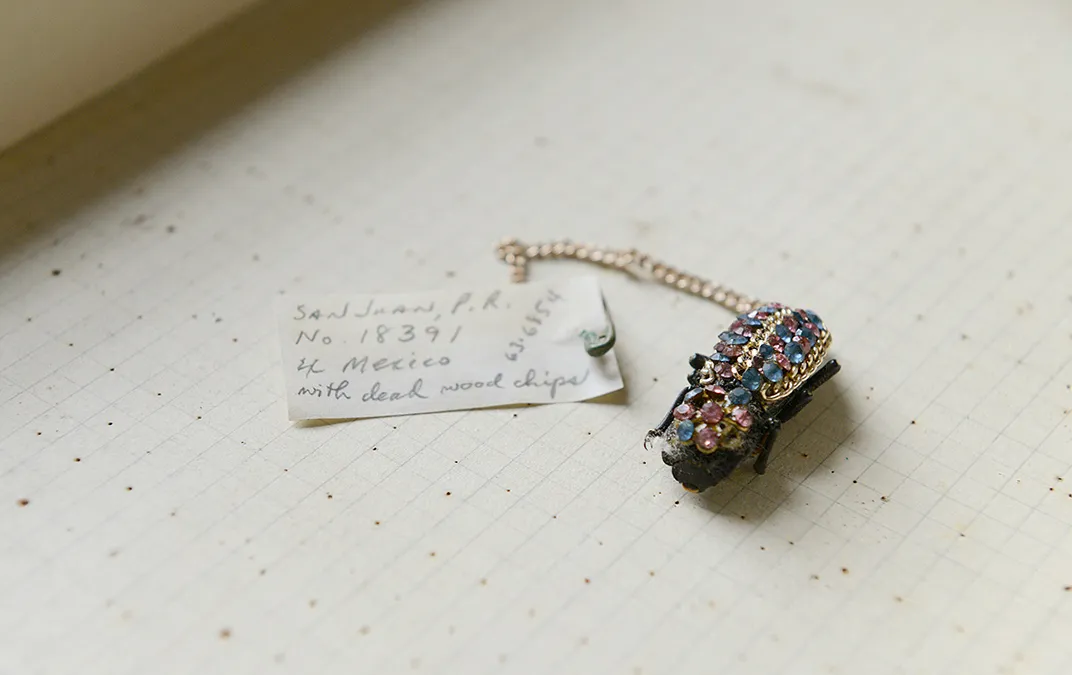

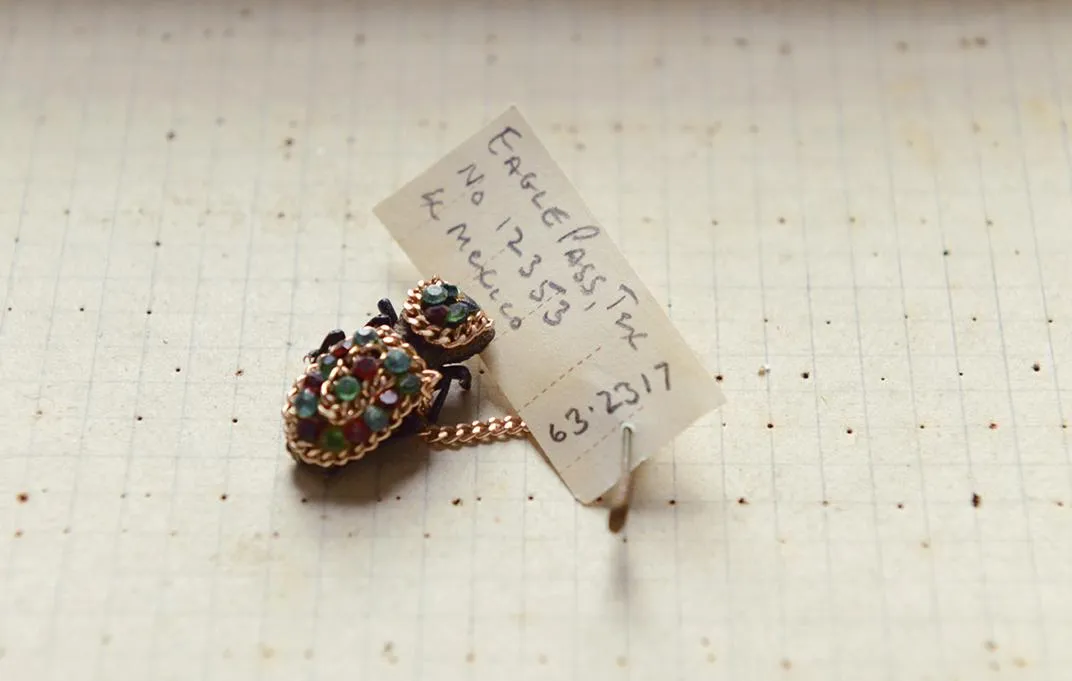

But that's not entirely accurate. Perhaps Gold had never met the makech, a beautiful beetle from Central and South America that has been worn as a living pendant for centuries. Today, vendors in Mexico sell the beetles covered in rhinestones, each one fixed with a gold chain and pin that serves as a leash, so that the bedazzled bug can walk around on the wearer's shirt.

"The novelty of a tethered jewel beetle on the lapel never fails to attract attention," former UCLA entomologist Charles Leonard Hogue writes in his 1993 field guide Latin American Insects and Entomology.

The beetles have definitely caught the eyes of officials with U.S. Customs and Border Patrol—according to USDA regulations, live animals can't cross the border without the necessary permits. Today, several confiscated specimens are glittering among the Coleoptera collections of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

If the idea of mobile insect brooches makes you squirm, their backstory may soften the sartorial blow. Hogue and other beetle curators report that the makech, or maquech, is linked to a Yucatán legend involving an ancient princess—often identified as Maya nobility—and her lover. The story has several variations, but the most popular say that the pair's love was forbidden. The princess was heartbroken when they were discovered and her lover was sentenced to death, so a shaman changed the man into a shining beetle that could be decorated and worn over the princess's heart as a reminder of their eternal bond.

This romantic tale may help to calm the squeamish and boost sales, but it doesn't seem to have an obvious analog in known Maya mythology, says Raul Aguilar, an artist based in San Francisco who grew up Mexico City and has owned a makech.

"There are a lot of traditions in that part of Mexico, and it is very muddy as far as which culture the makech comes from," says Aguilar. "Maya culture is pretty well documented—they had writing and stelae and books. If they had this legend, we would know something about it." He suspects the story is just something vendors tell the curious, although elements of it do echo certain traditions in the pre-Columbian cultures of the Yucatán, such as the idea of a shape-shifting shaman and the use of living animals as offerings in religious ceremonies.

Aguilar first encountered the makech as a child in the 1970s, when he bought one from a plaza vendor during a family trip to Veracruz. "It's not really a fashion trend so much as a curiosity. You wouldn't wear it to a party," he says. He decided to remove the jewels and leash and let the unadorned beetle roam free inside a house planter, where it lived for several months without seeming to eat or drink.

This strange ability to survive on almost nothing is tied to the bug's life as a dry forest dweller. Known to science as Zopherus chilensis, the makech is a neotropical insect that ranges from northern Colombia and Venezuela to south-central Mexico, where it prefers to hang around decomposing wood in relatively hot, arid regions. These particular beetles probably became associated with jewelry because they naturally have a muted golden hue speckled with black, so they already seem like ancient Maya treasures come to life. Ease of care only adds to the appeal.

"It doesn't take much to keep them happy. They need to eat a little starchy material, but they can survive for a long time with no water," says Warren Steiner, an emeritus beetle researcher at the Natural History Museum. "The larvae would start from an egg and then start munching on rotten wood, probably getting nourishment from lichen and fungi," he says. "The adults are often found under logs, bark stumps, that kind of thing. They're wood scavengers, and really sluggish. They usually play dead when you find them." The entire Zopherus genus is also flightless, he adds, so catching them wouldn't be that difficult.

Finding them, on the other hand, can present more of a challenge. Little is known about the beetle's general population status, but Steiner thinks the bugs are not generally abundant, in part because they reproduce more like elephants than fruit flies. "This beetle has a slow life cycle," he says. "They live a long time waiting for the right moment to lay eggs. They're also going to be hard to see—you just need to get lucky and turn over the right chunk of wood."

In Mexico, groups of men called "Los Maquecheros" find and collect adult makech beetles in the wild, using specialized training to sift through decomposing vegetation on the forest floor, according to a 2014 paper in Cuadernos de Biodiversidad by researchers in Spain and the Yucatán. Live bugs are delivered directly to local artisans, who decorate them for sale to tourists for around $5 to $10.

Local trade in wild makech beetles has been regulated on a community basis since the 1800s, but even today the practice isn't addressed by national laws, the researchers note. That means producing and selling makech "involves resource extraction without knowing the vulnerability of the species Z. chilensis," the team writes. As a conservation measure, some Mexican researchers are now looking into breeding the insects rather than relying on capturing them in the wild.

The practice has also drawn ire from animal rights activists, who protest the use of any living thing as ornamentation: “Beetles may not be as cute and cuddly as puppies and kittens, but they have the same capacity to feel pain and suffer,” PETA spokesperson Jaime Zalac told The Monitor newspaper in 2010.

"I don't think cruelty to animals is ever justified, but also people's culture is hard to judge when you are really not familiar," Aguilar says, adding that most artisans at least seem to limit the gems and beads they use so that the insect has free range of motion. And Steiner notes that the beetles are fairly hardy, so they would be easy to care for as pets once you know how. "They can't take too much heat, and a lot of handling probably isn't good for them. But they are pretty tough," he says.

Just remember that if you do hope to make a makech part of your household, you'll need a warm, dry terrarium, some lichen-crusted logs and—if a border crossing is involved—the proper permits.