Meet Mr. Wizard, Television’s Original Science Guy

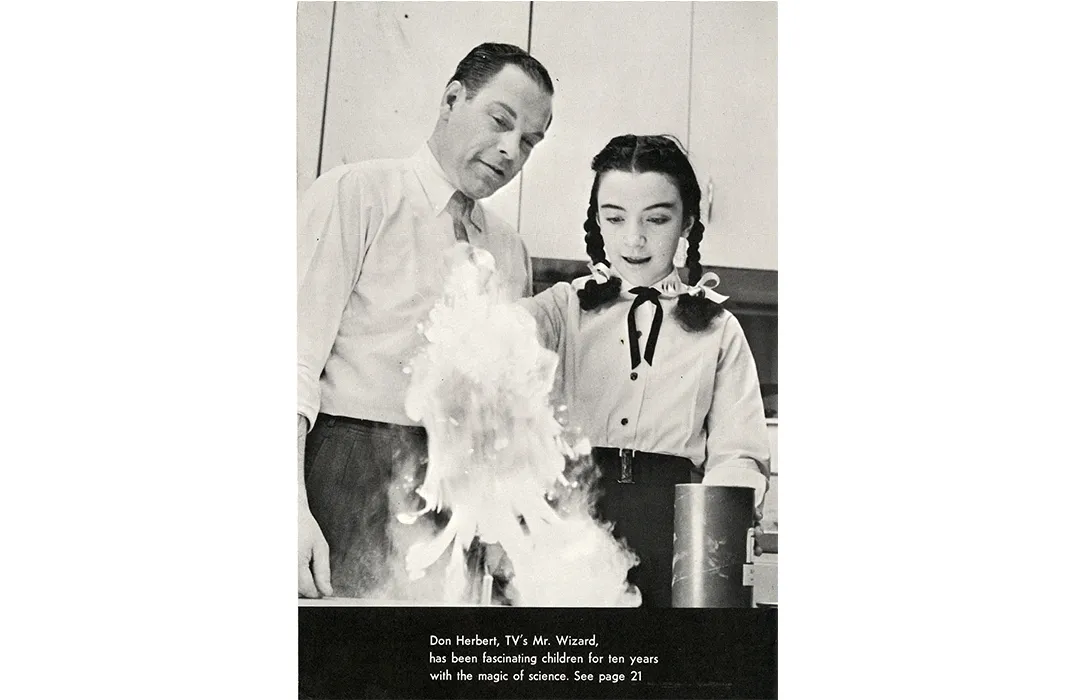

In the 1950s and 1960s, Don Herbert broadcast some of the most mesmerizing, and kooky, science experiments from his garage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/31/29313dc3-82bf-4a76-8a44-90e63647bd06/ac13260000004web.jpg)

It's an open argument of who was more famous at the time: the ascerbic comedian debuting a brand-new late-night comedy show on NBC or the show business veteran of the 1950s and '60s who entertained children with science. But when Don "Mr. Wizard" Herbert made an appearance on David Letterman's premiere episode on February 1, 1982, it was clear that the renowned science educator could entertain audiences of any age.

As Herbert inflated a baby bottle nipple using soda water, with Letterman commenting with his characteristic shtick, the audience roared in approval. It was just another example of Mr. Wizard explaining phenomena like electricity and air pressure with the aid of everyday materials like eggs, bottles, spoons and straws.

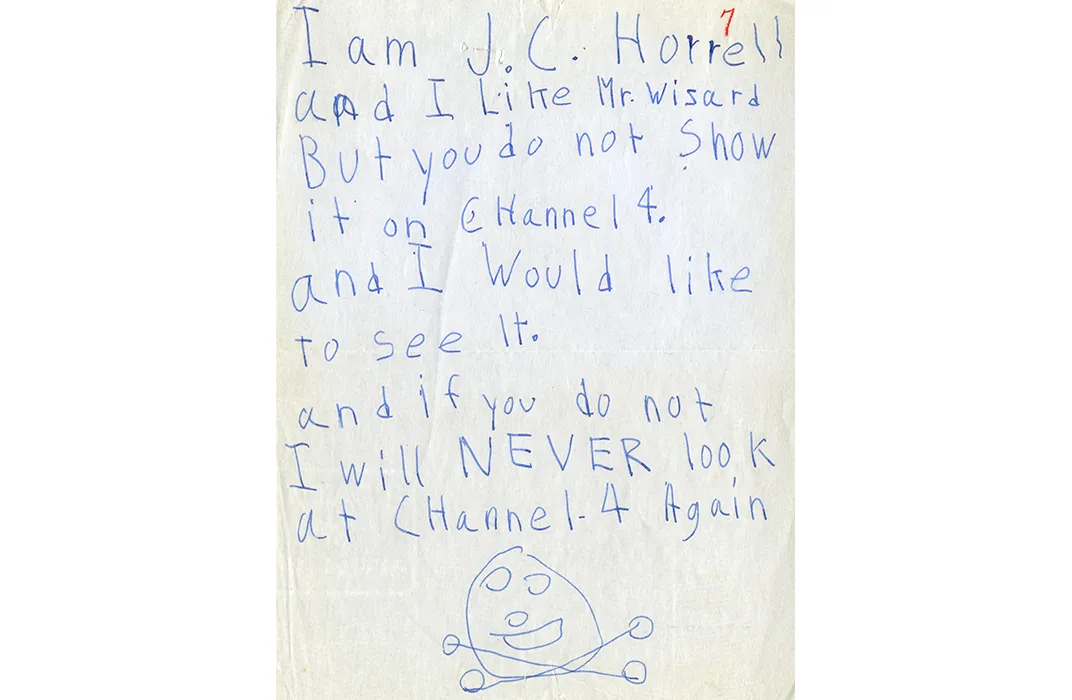

From 1951 to 1965, Herbert hosted “Watch Mr. Wizard,” a half-hour weekly show. Broadcast from his garage studio, the program was geared towards children, but kids weren’t his only fans. In addition to Letterman, Herbert’s copious fan mail includes paeans from parents all over the country, as well as a letter from a woman who began, “If I don’t write this, I’ll explode.”

A large collection of his documents and photos were recently donated to the Archives Center of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History by Herbert’s step-daughter and her husband, Kristen and Tom Nikosey. A small selection from the archive is on display through October 2, 2015, in the museum's newly renovated west wing, but the bulk of the materials are available by appointment.

A quick browse through the archive turns up Herbert’s original episode notes, which include detailed photos and instructions for many of his on-air demonstrations. On one of the pages for the egg-in-a-bottle experiment (which he performs second in the Letterman clip), a handwritten margin note says, “Do Wiz version—lit match atop shelled egg into inverted milk bottle.”

Herbert’s notes reveal an educator who was particular about science, but also about spectacle. He operated at a time when television had enabled more visual storytelling. Most kids’ programming was still cartoons.

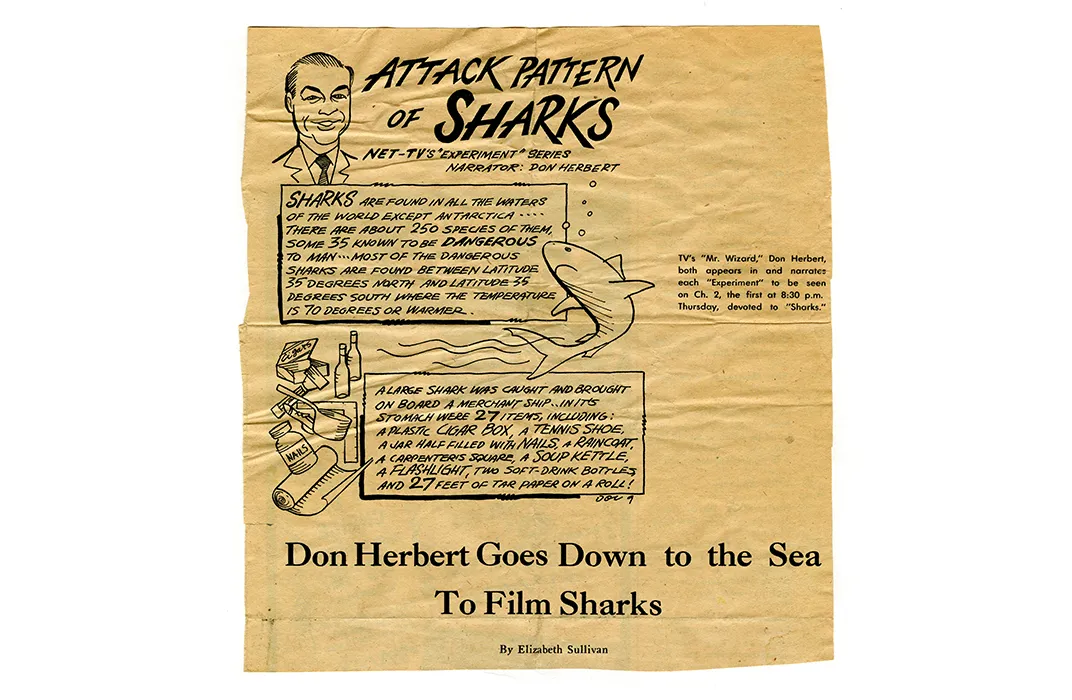

“His importance was to make science comfortable for children,” says Marcel LaFollette, a Smithsonian researcher and historian who has written a book about science on American television. “He was interested in science, but he liked being dramatic.” Herbert enjoyed the worlds of science and entertainment; where others might have seen tension, he saw opportunity. He studied secondary education (with a focus on English and general science) in college in Wisconsin, but his extracurricular work was in theater.

Some of his contemporaries—including Lynn Poole, who hosted an award-winning weekly live science show from 1948 through 1955 called the “Johns Hopkins Science Review”—embraced esoteric subjects. Poole invited scientists onto his show as guests. Not so with Mr. Wizard.

“When you watch Poole he’s a natural on TV but you don’t have a feeling that he’s talking to the 7- and 8-year-olds in the room, he’s speaking as if to an adult,” says LaFollette.

By contrast, Herbert and a child assistant would do experiments with materials like balloons and eggs. NBC cancelled Watch Mr. Wizard in 1965, but the show was revived as Mr. Wizard’s World on Nickelodeon in 1983.

“He said, ‘don’t let those producers put you in a lab coat,’” says Steve Spangler, a television veteran who has appeared on the "Ellen DeGeneres Show" and been nominated for multiple Emmy awards. Back in 1991, when Spangler got his first TV job hosting a show for children, he called Don Herbert. Herbert’s advice about lab coats, says Spangler, went beyond the cosmetic.

“He said, ‘you need to make science accessible to the masses. A lab coat can put people off—kids don’t like that. That’s why [my set] wasn’t called my lab, it was called my garage, and we used household materials, not lab gear,’” Herbert told Spangler.

On one occasion, Spangler says, Herbert struggled with the line between science and entertainment. One of Herbert’s “signature” demonstrations—the one with the expanding baby bottle nipple, shown in the Letterman clip—made for great TV, but Spangler says that Herbert later lamented that the experiment was more notable for its “gee whiz” element than for the principles it actually teach.

Still, Herbert’s style and delivery made a profound impression on young viewers, as did his use of everyday materials in his experiments. In 1952, he got a letter from a group of young viewers in Jacksonville, Florida, who wanted to “start a Mr. Wizard Science club.”

The club, which met at one of the boys’ houses, tried to replicate Herbert’s experiments. Herbert’s publicity team wrote back, sending the fledgling group a set of membership cards and a charter. The correspondence between the fans and the celebrity lasted years, and over time more clubs formed. Those fan clubs would eventually count more than 100,000 members, according to an NBC promotional article from the time. In 1956, one of the original Jacksonville founders wrote to Herbert again, beginning his letter by saying, “maybe you do not remember me. Like you say, I am fourteen now and like the other “Pioneers” have become interested in girls and ‘Rock & Roll’ music. . . . Although our club does no longer exist, science is still very interesting to me.”

Herbert replied: “I certainly do remember you. . . there are now 5,000 MR. WIZARD Science Clubs in this country, Canada, Mexico and Hawaii and, in a way, you are responsible for them, having suggested the idea.”

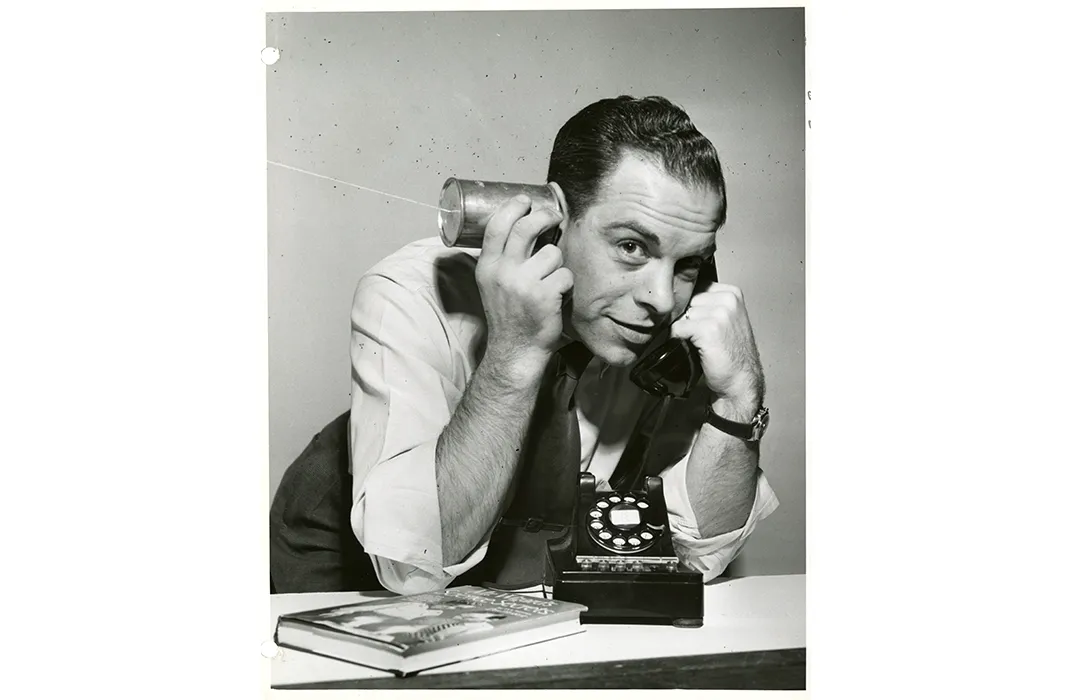

In another fan letter, a mother thanks Herbert for having answered a cold call from her 5-year-old son: “[His siblings] told him if he wanted to call he would have to do so all by himself. . . . The operator told him to dial 411 which he did, got your number and spoke to you.”

None of Herbert’s predecessors or contemporaries achieved that kind of resonance with children, says LaFollette. His relationships with his fans proved his most enduring legacy. Even in the archives, Herbert’s fan mail is some of the best reading, says archivist Alison Oswald, who catalogued and organized much of the 27-cubic-foot collection that fills several dozen neatly organized boxes. Early fan letters are handwritten or typed on crumbling paper, harking back to a time when people still used the post to communicate, while later ones include printouts of emails.

For the Nikoseys, who made the donation, Don Herbert’s public history has become their personal mission. They run the website MrWizardStudios and they keep up with some of Herbert’s most devoted fans.

“People still keep in touch with us,” says Tom Nikosey, a graphic designer. He says that he recently tracked down the author of a piece of Herbert’s fan mail, and had a long conversation with him. “He raved about Mr. Wizard, and we had this really wonderful exchange.”

Herbert passed away in 2007. In an obituary that ran in the Los Angeles Times, he got an ovation from someone who’s followed in his footsteps: the science educator Bill Nye. Nye wrote, “If any of you reading now have been surprised and happy to learn a few things about science watching "Bill Nye the Science Guy," keep in mind, it all started with Don Herbert. . . [he] changed the world.”

"Mr. Wizard," a display of documents and archival materials from the popular television science educator is on view through October 2, 2015 at the National Museum of American History.

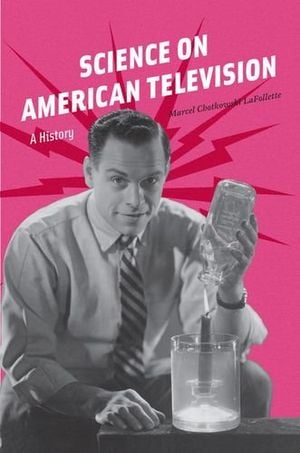

Science on American Television: A History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/48/36483768-985b-411d-932c-37838731d181/ac1326000001401web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)