Meet the Real “Most Interesting Man in the World”

On view at African Art, a retrospective of Eliot Elisofon, who drank scotch and was allowed to touch the museum’s art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/fe/e9fed59d-0281-4a78-bf61-89a0f3a2016e/nmafa_ee-vintageprint-030.jpg)

The real "Most Interesting Man in the World" didn’t sell Dos Equis; Eliot Elisofon took pictures. And yes, Elisofon was allowed to touch the artwork in the museum, because he gave it to them. He also put the Brando in Marlon. And strippers kept photos of him on their dressing tables.

His Latvian last name (accent the first syllable: EL-isofon) so confounded General George S. Patton that the commander simply called him “Hellzapoppin.”

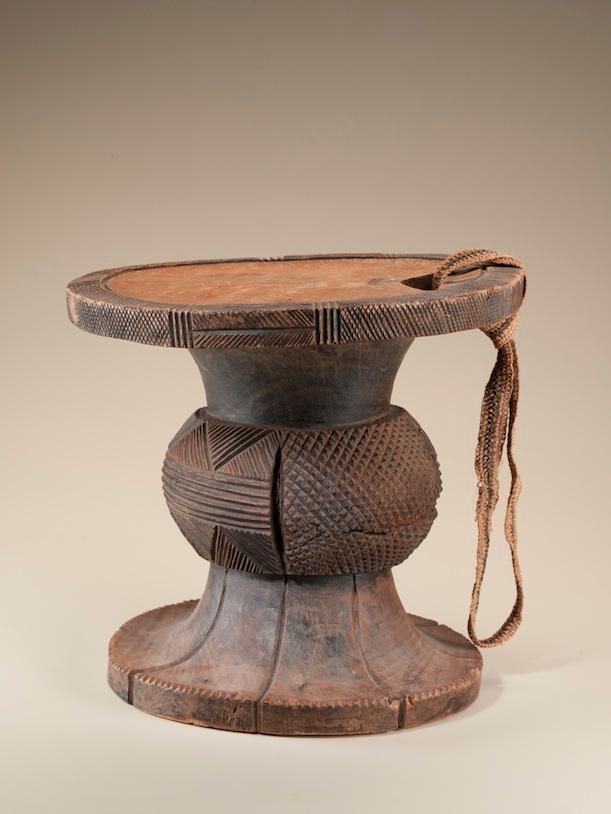

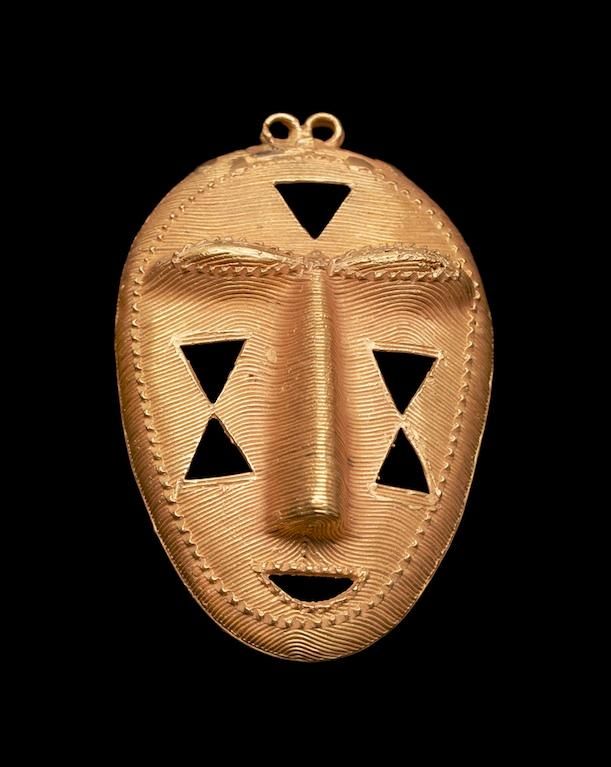

The most interesting man in the world didn’t think of himself as a good photographer, but rather as the “world’s greatest.” And while ceaseless self-promotion was his game (he hired a press agent and a clipping service), the output of his camera can be measured: The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art boasts more than 50,000 black-and-white negatives and photographs, 30,000 color slides and 120,000 feet of motion-picture film and sound materials. In addition, the photographer collected and donated more than 700 works of art from Africa. Hundreds of other images are owned by the Getty Archives, and his papers and materials are housed at the University of Texas at Austin.

Beyond his prodigious photographic output, his life was a whirlwind of travel, food, wives (two marriages ended in divorce) and celebrity friendships. His good friend the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee kept his photo on her vanity table; he helped establish the image of Marlon Brando in 1947, photographing the rising star in his role as Stanley, kneeling in disgrace before his wife, Stella (Kim Hunter), in the Broadway production of Streetcar Named Desire. Elisofon's passion for travel was interrupted only by occasional home visits to his New York apartment or his Maine beach enclave. He would later claim that he’d traversed as many as two million miles in pursuit of his art. Painter, chef, documentarian, filmmaker, art collector and connoisseur, and naturally, the most interesting man in the world knew how to drink and dine on the go.

“I am having some Brie and crackers and a scotch and water. I know how to get Brie exactly right,” he once said. “You have to carry it on a TWA plane, get the Stewardess to place it in a bag of ice cubes, then in Tel-Aviv leave it in your room overnight, then keep it for two days in the ice-box of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem—it's too hard anyway. From Tel-Aviv to Bombay keep it under your seat—well wrapped in plastic—One night in the Taj Mahal Hotel room and a short plane ride in Keshod—and it is just right, not too runny but it would be if left in the single small refrigerator they have in the Guest House.”

While Elisofon's portfolio includes everything from celebrity homes in Hollywood, to soft-coal mining in Pennsylvania, cocaine trading in Bolivia and Peru, the King Ranch in Texas and the North African Theater during World War II, his most enduring and significant work would come from the nine expeditions he made to Africa. Beginning in 1947, when Elisofon crossed the continent from “Cairo to Capetown,” he became the first Western photographer to portray Africa’s peoples and traditions without stereotype or derision.

Recently, a retrospective of his work, “Africa ReViewed: The Photographic Legacy of Eliot Elisofon,” went on view at the African Art Museum in celebration of the 40th anniversary of the donation the photographer made of his images and art works to the museum. “Elisofon’s breathtaking images,” says director Johnnetta Betsch Cole, “capture the traditional arts and cultures of Africa and are simply unparalleled. The enduring brilliance of his photographs expose a new generation to the breadth, depth and beauty of Africa.”

Elisofon was a staff photographer at Life magazine from 1942 to 1964, and one of the first freelancers at Smithsonian magazine when it began publishing under former Life editor Edward K. Thompson in 1970. In fact, an Elisofon image, one of the most requested photos from the museum's collections, graced the magazine’s January 1973 cover and features a Baule woman of the Ivory Coast holding two ceremonial chasse-mouches, or fly whisks, made of gold-covered wood and horsehair imported from the Sudan. His accompanying story tells of his visit to meet with a Baule chief, the Ashanti ruler in Ghana and other West African peoples.

"Among the crowd that day, I saw seven men dressed alike in brilliant red cloth with gold tablets covering the tops of their heads," Elisofon wrote. "Each tablet was decorated with intricate designs in wrought or beaten gold. . . . No one—traveler, anthropologist, art historian—has made any reference that I have been able to find to these tablets, yet they were clearly centuries old, their edges worn away by use."

"Elisofon used his brains and his talent to lay his hands on the world," says former Smithsonian editor Timothy Foote, who worked with the photographer when they served together at Life.

“For generations foreign photographers had misrepresented Africa as a mysterious or uncivilized continent full of exotic animals, backward peoples and strange landscapes, “ wrote curator Roy Flukinger for a 2000 exhibition of the photographer’s work at University of Texas at Austin. “The limitations and/or prejudices of many 'objective' documentary photographers and writers had discolored the entire portrait of a vibrant land and its myriad cultures. Elisofon's social consciousness and inherent humanness would not tolerate it. He held that ‘Africa is the fulcrum of world power’ and he sought to have America ‘wake up to that fact.’ ”

"Photo historians," says the shows co-curator Bryna Freyer, "tend to stress his technical achievements. As an art historian I tend to look as his images as a useful way of studying the people and the artifacts, because of his choice of subject matter."

He photographed artists at work, she adds, "capturing the entire process of the production of an object. And he photographed objects in place so that you can see the context of masks, their relationships to the musicians and to the audience. I can use [the image] for identification and teaching."

"On a personal level, I like that he treated the people he was photographing with respect," she adds.

The exhibition on view at African Art includes 20 works of art that the photographer collected on his trips to the continent, as well as his photographs, and is complimented by a biography section composed of images of his exploits.

The photographer as the subject of another's lens can sometimes be regarded as insult, and for Elisofon it was injury added to insult. In 1943, Elisofon was aboard a transport aircraft that crashed on takeoff, but he managed to escape the burning wreck. Grabbing his camera, he somehow lost his pants, he went straight to work documenting the scene before collapsing in exhaustion. Later, his frustration was described as titanic when the images he shot that day were not selected by his editors back in New York. Instead, they chose an image that another photographer got of Elisofon shooting the scene in his boxers.

The focal piece of the exhibit is a classic photo of Elisofon on location in Kenya, with Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance hovering above the clouds like a mythic spacecraft. The image taken by an unknown artist depicts the peripatetic adventurer as "explorer photographer" says the show's co-curator Amy Staples. "For me that image is symbolic of the title of the show, Africa Re-Viewed, which is about the role of photography and constructing our view and knowledge of African arts, and its cultures and its peoples." Another highlight is a documentary film, Elisofon made of the Dogon people of Mali, carving a Kanaga mask, which is used in ceremonial rituals that are regarded as deeply sacred.

Born to a working-class family and raised on New York City’s Lower East Side, Elisofon earned enough money as a young entrepreneur to afford tuition at Fordham University. Photography would be his hobby until he could make it pay. And he would ultimately rise to become the president of the highly prestigious Photo League, where he lectured, taught and exhibited his work. The young photographer would also pick up a brush and prove his talent as painter and artist. In the nascent days of color photography and filmography, he would eventually apply what he knew about the intensity, saturation and hue of color as an artist in Hollywood. Serving as a color consultant in the motion pictures industry, Elisofon worked with John Huston on the 1952 Academy Award-winning Moulin Rouge.

Several of his illustrated books, including the 1958 The Sculpture of Africa, co-authored with William Fagg, have become iconic. And the photographer was on location for the arduous shoot when Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn were filming The African Queen. He would shoot dozens of other film stars, including John Barrymore, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Rudy Vallee, Natalie Wood, Kirk Douglas, Ira Gershwin and Rock Hudson.

Yet some time prior to his death, in 1973, at age 62, of a brain aneurism, Elisofon would become circumspect about his wildly diverse career, reining in his earlier bravado.

"Photography is too personal a medium with which to achieve greatness easily. I'm too diverse a man to be a great photographer. I have discipline, motivation. I'm a good photographer. But I'm a writer, painter, editor, filmmaker, too. I'm a complex human who needs to satisfy human needs. You can't be great without giving everything you've got to a single art," he said, and perhaps this is where the real life "Most Interesting Man in the World" departs from the man of advertising fame.

"I haven't done that," he said, and then he added, "I'm also a talker."

"Africa Reviewed: The Photographic Legacy of Eliot Elisofon" is on view at the African Art Museum through August 24, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)