Museums Are Now Able to Digitize Thousands of Artifacts in Just Hours

At the American History Museum, a collection of rarely seen historic currency proofs are being made ready for a public debut

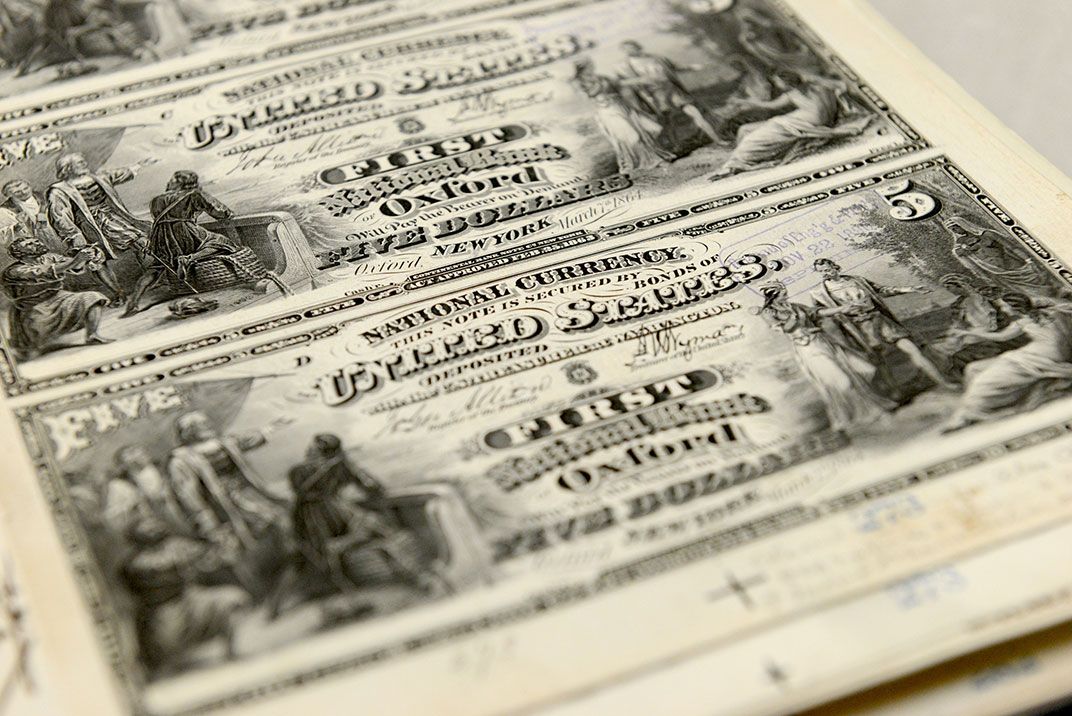

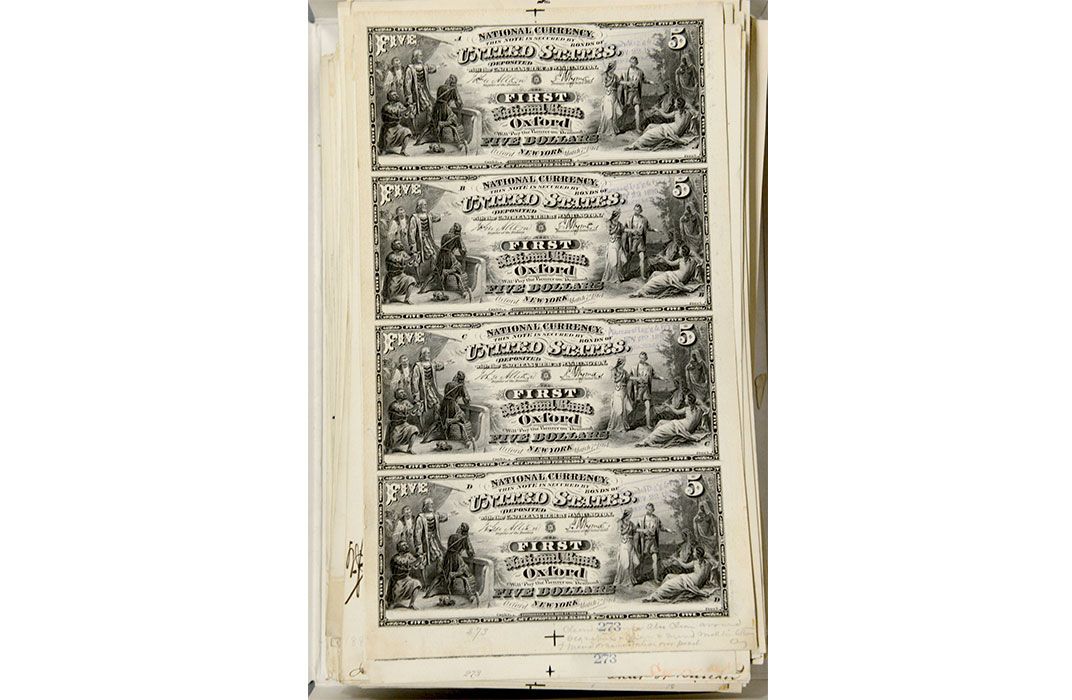

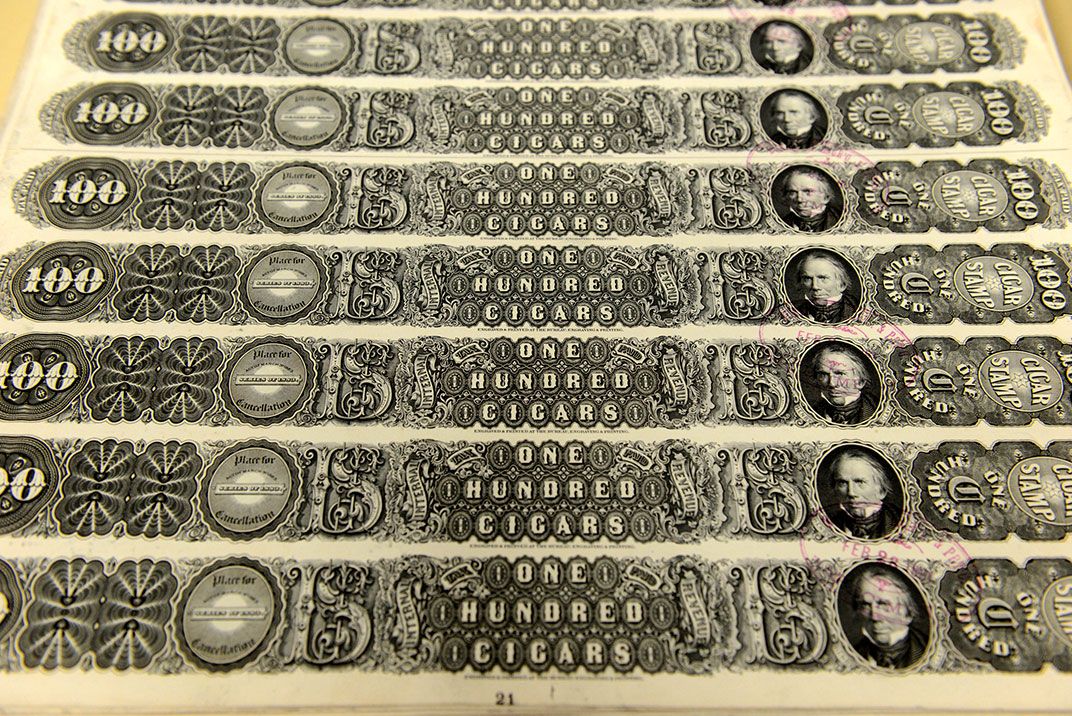

In the age of credit cards, Bitcoin and mobile payments, it's hard to believe that the proofs once used to create paper money can be as significant as priceless works of art. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, American states issued their own bank notes, made from metal plates engraved by hand. For immigrants at the time, the money in their pockets meant more than just opportunity; the scenes printed on them, such as Benjamin Franklin flying his famous kite, taught them about American history.

As the Smithsonian works to digitize its collection of 137 million items, the Digitization Program Office has turned to the National Numismatic Collection housed at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History along with other legal tender such as bank notes, tax stamps and war bonds. The 250,000 pieces of paper will become the Institution’s first full-production “rapid capture” digitization project.

The project team, made up of 20 people hailing from a handful of departments across the Institution, began its pilot effort last February and moved forward in October, around Columbus Day. That’s fitting, because some of the proofs depict Columbus discovering America. “This is a lost art form,” says Jennifer Locke Jones, chair and curator of the Division of Armed Forces History. (Even Jones admits she no longer carries cash.)

Last summer, the Digitization Office captured the bumblebees at the National Museum of Natural History. Earlier this month, the Freer and Sackler galleries made their entire collections of 40,000 works available digitally, the first Smithsonian museums to do so.

The term “rapid capture” refers to the speed of the workflow. Before this process was in place, digitizing a single sheet could take as much as 15 minutes, at a cost of $10 per sheet. Now, the team works through 3,500 sheets a day, at less than $1 per sheet.

The process uses a conveyor belt and a custom-designed 80 megapixel imaging system, making details available to the world that had only ever been seen by a select few. (By contrast, the new iPhone camera has only eight megapixels.) The conveyor belt resembles the ones used by security at airports. Markings on the belt guide team members in placing the sheets. The belt advances when the sheet at the end has been removed. Such equipment has never before been used in the United States.

Before such state of the art technology, digitizing that daily amount would have taken years, says Ken Rahaim, the Smithsonian's digitization program officer. “Prior to this,” Rahaim says, “nobody ever thought in terms of seconds per objects.”

Rahaim says the project is on schedule to conclude in March. Transcribing the information from the sheets into the online system must be done sheet by sheet, and will continue after digitizing has wrapped. The Institution has asked the public to help transcribe through its Smithsonian Transcription Center. For this project, transcribers have completed 6,561 pages, each with information about what bank and city the sheet is from, what date the original plate was made, and other numismatic details.

The quarter-million sheets, each unique, were used to print money from 1863 to 1930. They entered the Smithsonian’s collections from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing between the 1960s and 1980s, and because the original engraved plates no longer exist, these sheets are the only surviving record and essential to the country’s monetary history. “People have never seen this collection. Most numismatists have no idea what’s here,” Jones says. Some of the designs even came from works of art, including paintings now hanging in the nation’s Capitol.

Aside from the occasional sheets stuck together, which causes a few seconds of delay, things have moved smoothly. “There’s a large element of human checking that still needs to happen at every point in the process,” Jones says.

“We have unlocked the ability to do this efficiently and at a price that was unheard of before,” Rahaim adds. “Digitizing a whole collection, it was an abstract concept, but these processes are now making that a reality.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/91/a591411b-8611-4cfb-be11-6600169ad22b/4_dsc_2530-copyweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/9e/499ea756-990d-4958-83cd-54ece5c6b8a2/5_dsc_2574web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)