Nearly Two Million Years of Innovation, As Told Through Tools

Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum, will exhibit 175 objects that range from Paleolithic tools to space-age satellites

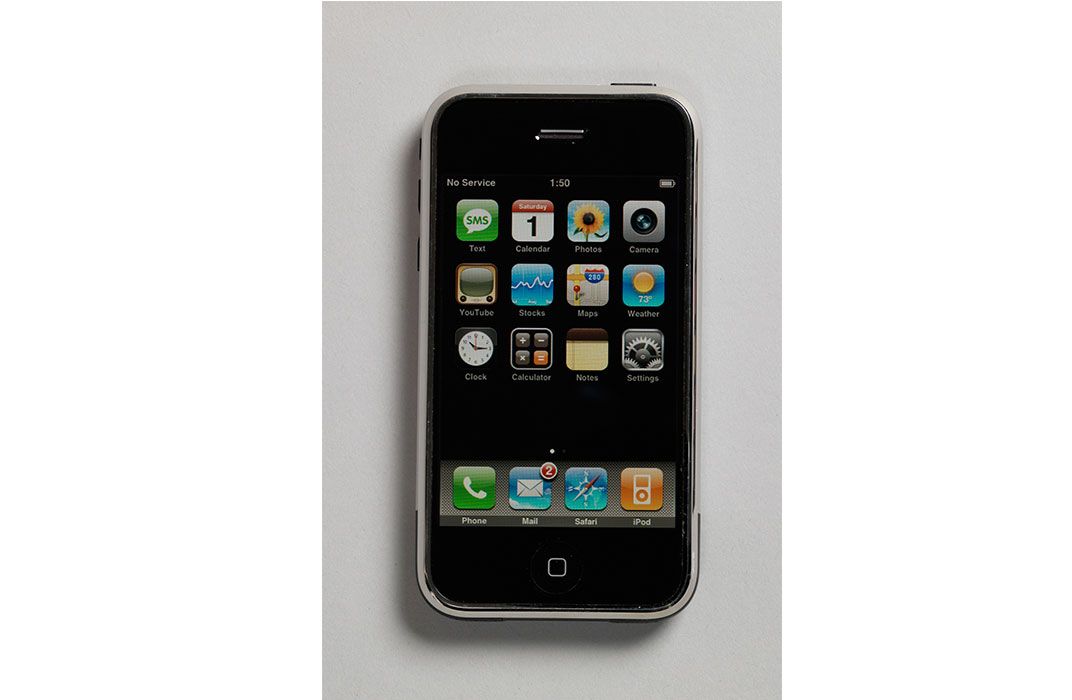

Tools can be simple or complex, but at their core, they're meant to be a solution to a particular problem. A knotted ball of Indian hemp, for instance, might seem completely different from a mechanical clock, but each represents one culture's attempt to keep track of time. From knotted time balls to modern iPhones, 175 tools tell the story of human ingenuity and innovation spanning nearly two million years in the Cooper Hewitt exhibit Tools: Extending Our Reach, on display through May 25, 2015. The exhibit is part of ten inaugural exhibits and installations that mark the museum's reopening December 12 after three years of renovation.

"The tools celebrate the ingenuity of the human spirit across time and culture," says Matilda McQuaid, the museum's deputy curatorial director. "Materials may vary, but they're using the skills and materials of their time, whether it's using the gut skin from beluga whales to create an absolutely windproof and waterproof parka, or technology of our contemporary time to look at the Sun, millions of miles away, to understand how what happens on the surface of the Sun reflects what is happening to us here on Earth. It's about how we push ourselves, as humans, regardless of where we are and what period we're from."

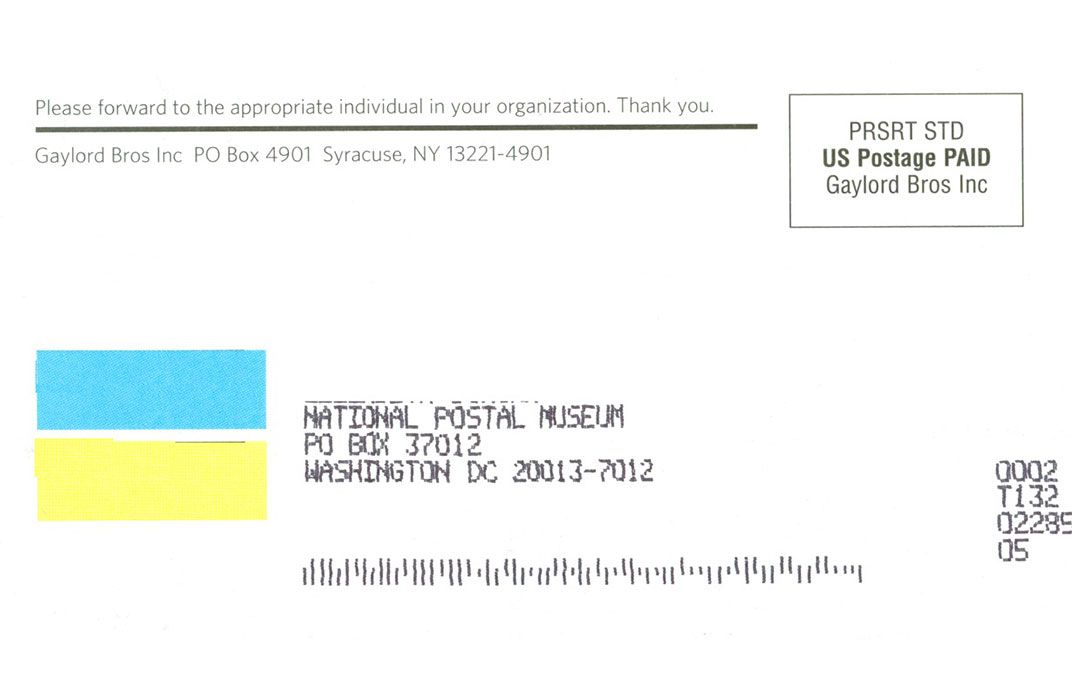

Selecting 175 tools to represent the evolution of human design was no easy task, but McQuaid and Cara McCarty, Cooper Hewitt's curatorial director, enlisted help from the nine of the Smithsonian Institution's museums and research centers in selecting which tools to highlight. They set up meetings with Smithsonian colleagues, asking each what their favorite tool was from their collection. The answers they received were, at times, unexpected, but helped shape the vision of the exhibition itself. At the National Postal Museum, for instance, McQuaid had her eye on a conveyor belt, because it revolutionized the ability for post offices to accurately sort huge quantites of mail. But instead, Postal Museum curator Nancy Pope recommended a postage stamp and intelligent barcodes—tools of transactions. Stamps revolutionized mail, Pope explained, by allowing people to prepay for postage, making mail quicker and easier to deliver. And the more recent use of intelligent barcodes allows each letter or package to have a unique code, which helps post offices better track and sort the mail.

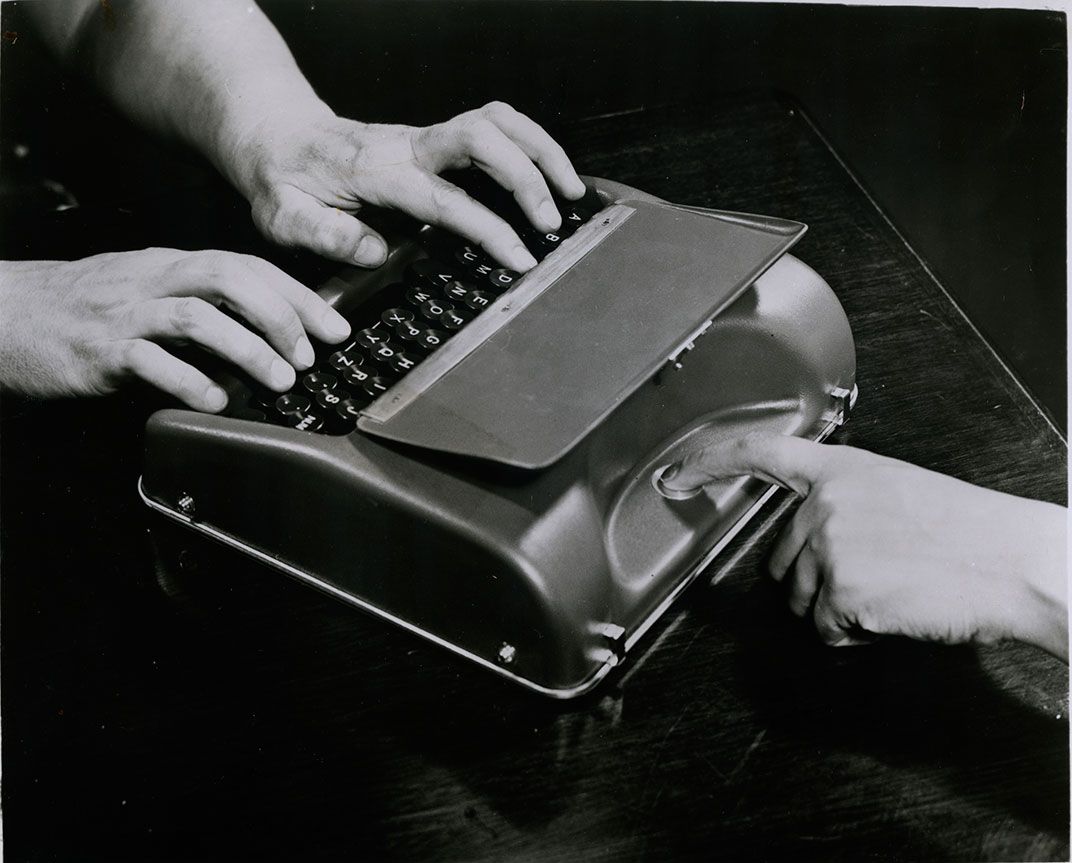

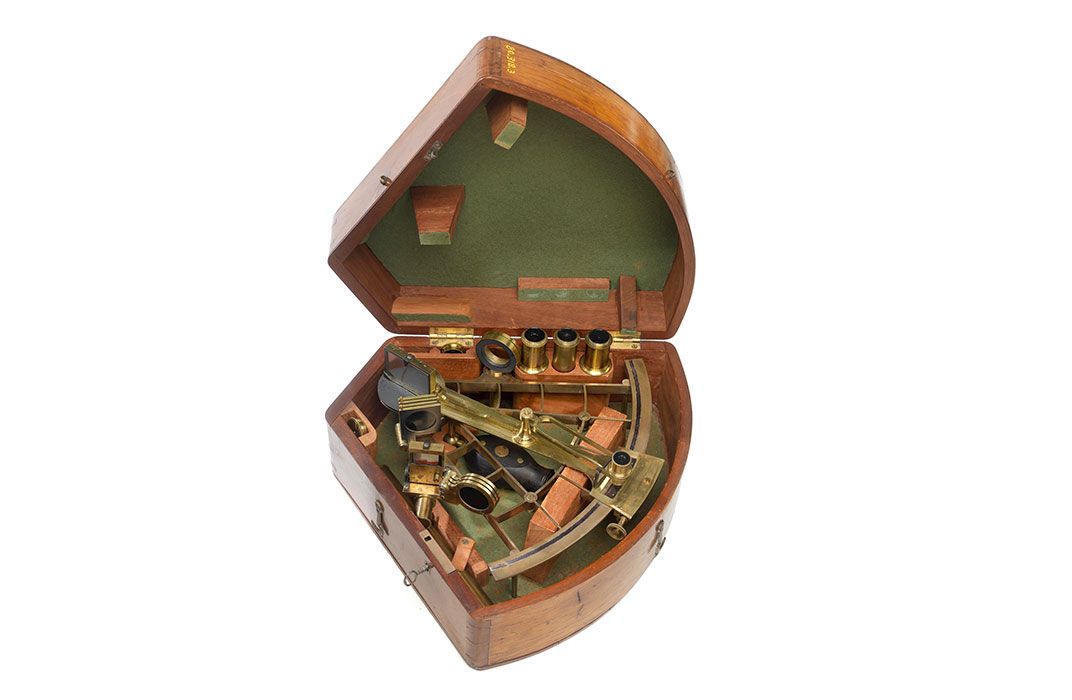

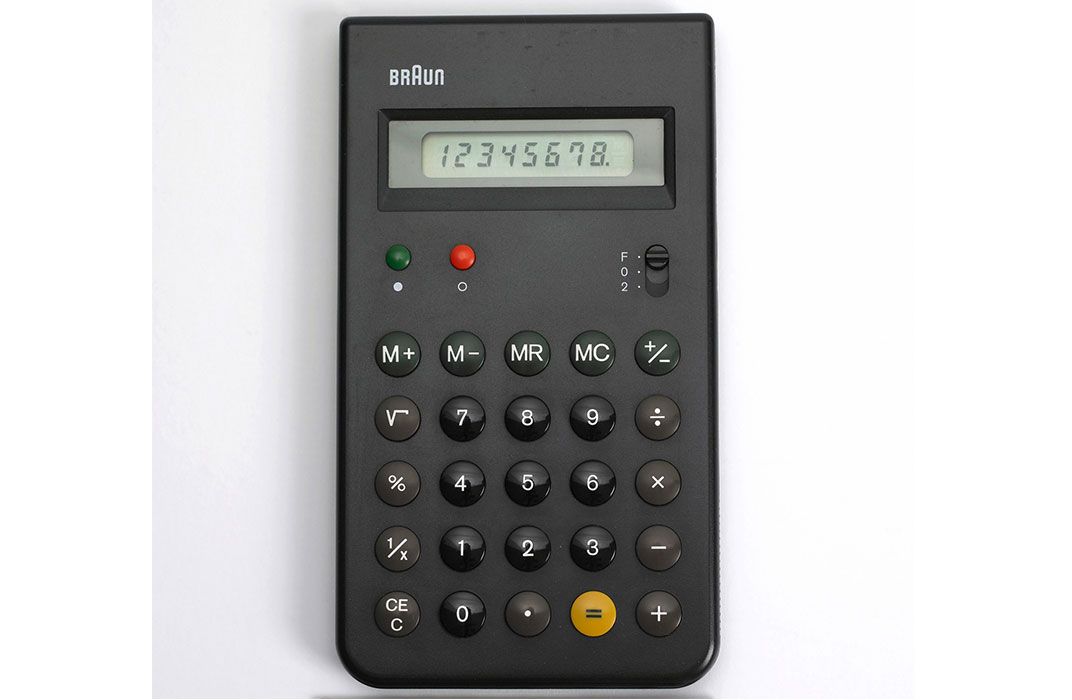

After several such meetings, McQuaid and McCarty began to see common threads forming between the tools—threads that they used to create the exhibit's seven subcategories: Work, Communicate, Survive, Measure, Make, Observe and Toolboxes. "We weren't interested in showing an evolution," McCarty says. "It was important that we not just talk about the chronology of tools, but we mix culture and time periods, always focusing on the purpose."

Though the items in the exhibit might seem like unique entities, McQuaid and McCarty were most interested in showing connections between one tool and the next. The iPhone and Paleolithic hand ax might seem completely different and used by different cultures and separated by thousands of years, yet both are designed to be multipurpose, small, portable tools. "We sometimes think that someone has a brand new idea that no one has ever had before, but so much of what we do is about connections, about our experiences and about references to other cultures and time periods," McCarty says.

After three years of renovations, Smithsonian's Cooper Hewitt Museum—the nation's only museum dedicated exclusively to design both historic and contemporary—has reopened to the public. Located in New York City's Carnegie Mansion, the renovated museum boasts 60 percent more exhibition space and features new, interactive technology that allows visitors to explore the museum's collections both physically and digitally. To celebrate the reopening, the museum is launching ten inaugural exhibits and installations, which collectively span 30 centuries and feature more than 700 objects.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)