Stories of Sports Champions in the African American History Museum Prove the Goal Posts Were Set Higher

The sports exhibition delves into the lost, forgotten or denied history of the heroes on the field

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/ef/1def6f04-a80a-4f52-8cf8-eb7a458a573b/dsc06121web.jpg)

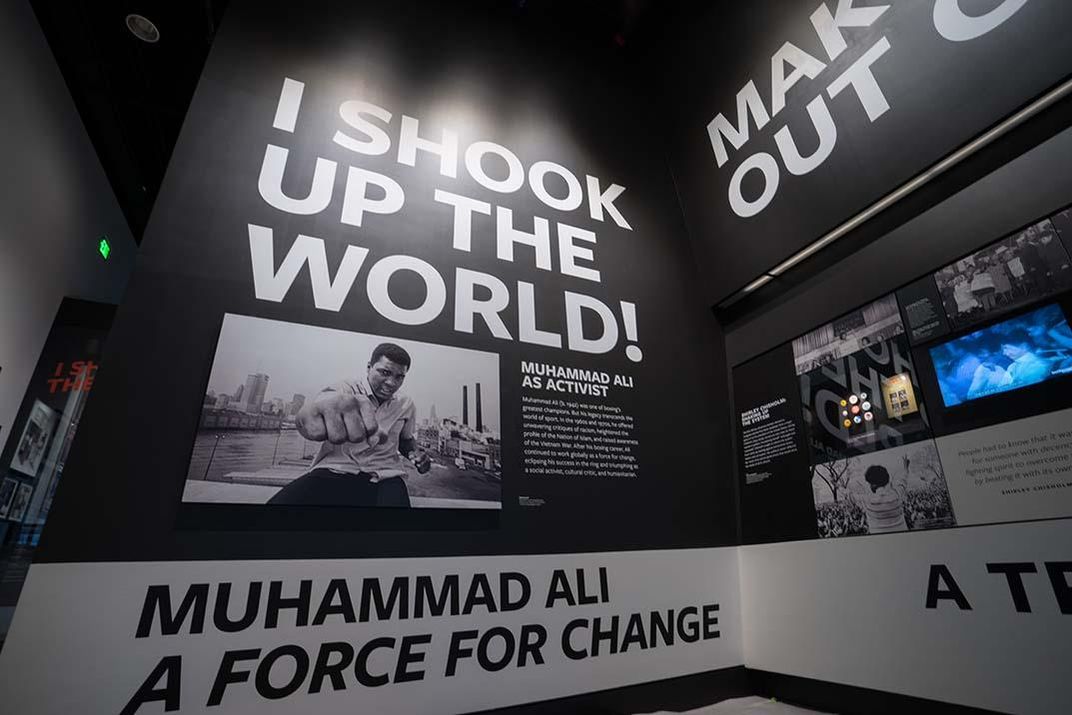

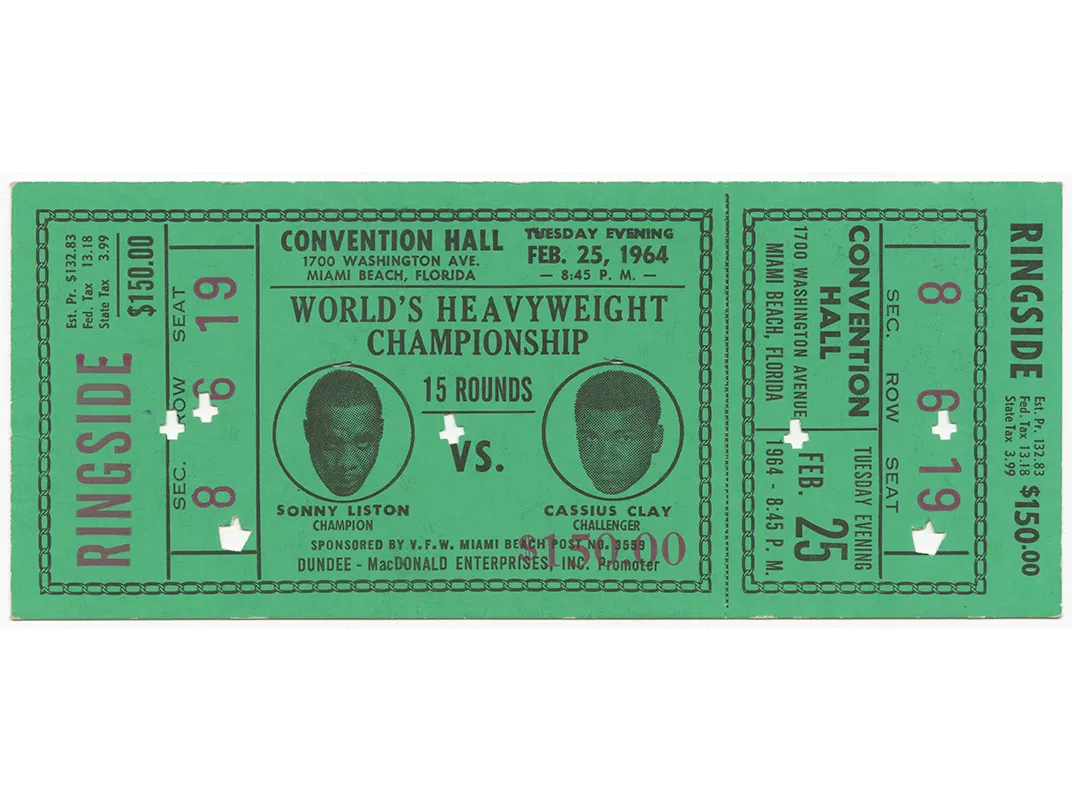

Former presidential candidate and civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson was thoughtful last fall as he strolled through the exhibition “Sports: Leveling the Playing Field” during the opening days of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Headgear worn by boxing legend Muhammad Ali at the 5th Street Gym in Miami during the 1960s caught his attention.

“I have to take some time to process it all. I knew Ali, particularly when he was out of the ring, when he was left in the abyss. I was there the night he came back into the ring,” Jackson says, referring to the four years during the Vietnam War when Ali was stripped of his heavyweight titles for draft evasion, and before his conviction was overturned in 1971 by the Supreme Court.

Jackson is walking by 17 displays called the “Game Changers” cases that line the hallway in symmetrical splendor. Inside each is a wealth of pictures and artifacts belonging to some of the greatest athletes in our nation’s history—from tennis star Althea Gibson, the first African-American to play in the U.S. National Championships, to pioneer Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in baseball.

“What’s touching me is I preached at Joe Louis’ funeral. . . . I was the eulogist for Jackie Robinson in New York . . . I was the eulogist for Sugar Ray Robinson,” Jackson says. “I was there when Dr. King was killed in 1968. I wept. I was there when Barack Obama was determined to be the next President and I wept. From the balcony in Memphis to the balcony at the White House was 40 years of wilderness. . . . So to be here with people who made such a great impact, all these things in the wilderness period made us stronger and more determined.”

The museum’s Damion Thomas, who curates this exhibition, says telling the stories of athletes who made such a difference in the nation’s history is an important part of the mission.

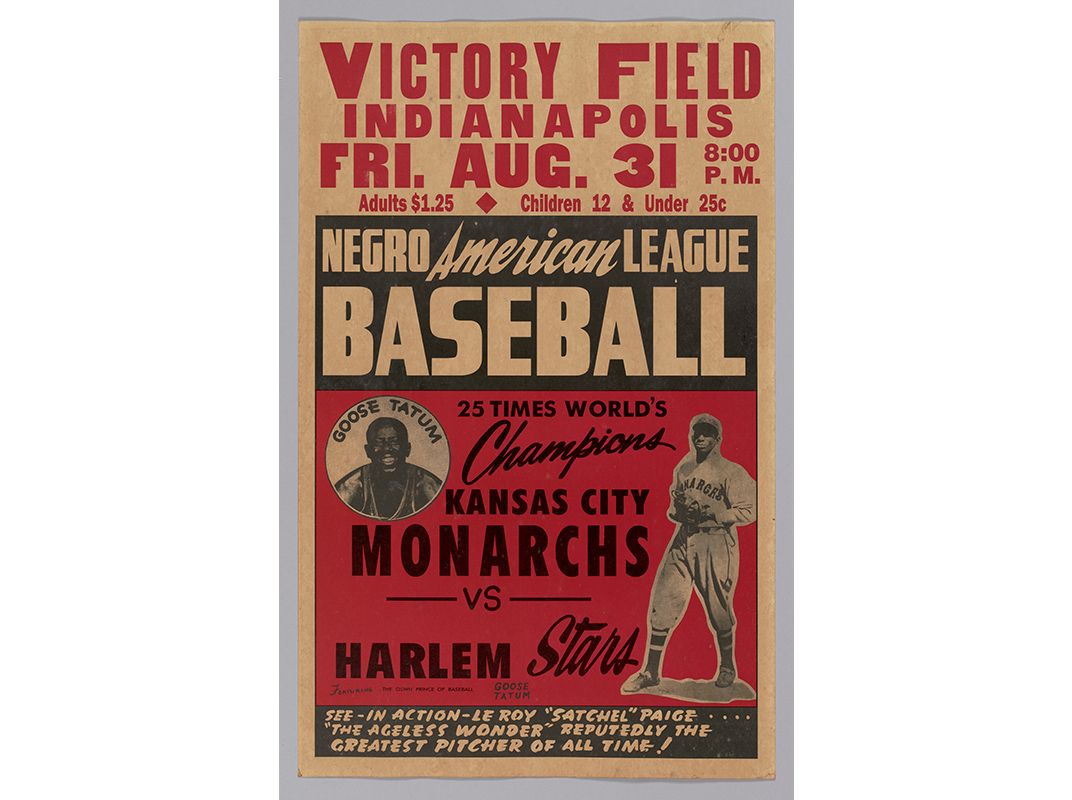

“A large part of what we attempt to do in this gallery is to introduce people to stories they think they know in unique and historically compelling ways,” he says. “Some important names . . . have been lost to history so the greatest beauty of this museum is that we can recapture history that’s been lost or forgotten, or even denied.”

Some of those names belong to black jockeys, such as two-time Kentucky Derby winner James "Jimmy" Winkfield, who today remains the last African-American to win the Run for the Roses, and Isaac Murphy, who was the first three-time winner of the Kentucky Derby. The storied history of African-American jockeys is featured in the first of the Game Changers cases.

“The Game Changers refer to people, places and institutions that changed the sports world or society. I wanted to go back as far as I could, back into slavery. One of the stories that takes us back into that institution is horse racing,” Thomas explains. “Many African-Americans were involved in horse racing, and learned the trade, learned to ride, learned to groom horses in enslavement. If you think about the first Kentucky Derby, African-Americans were 13 of the 15 riders, and then got pushed out. It is a part of history that people no longer understand or know, and have forgotten and I knew I wanted to tell that story.”

Thomas searched for artifacts from the 19th century and couldn’t find them. So he ended up looking to Marlon St. Julien, who raced in the Kentucky Derby in 2000. He was the first African-American to compete in that race in 79 years.

“So we have these artifacts, jockey silks and a riding whip from 2000 to talk about a much older story,” Thomas explains. “I remember traveling to a small little town, Shelbyville, In diana, to this tiny race track, and meeting with him and him just saying ‘What do you need?’ . . . That’s the story of this gallery, is that people have decided to entrust the museum with some of their most prized possessions and we’re really thankful that they’ve done so, and really honored to be the guardians and preservers of these important historical artifacts.”

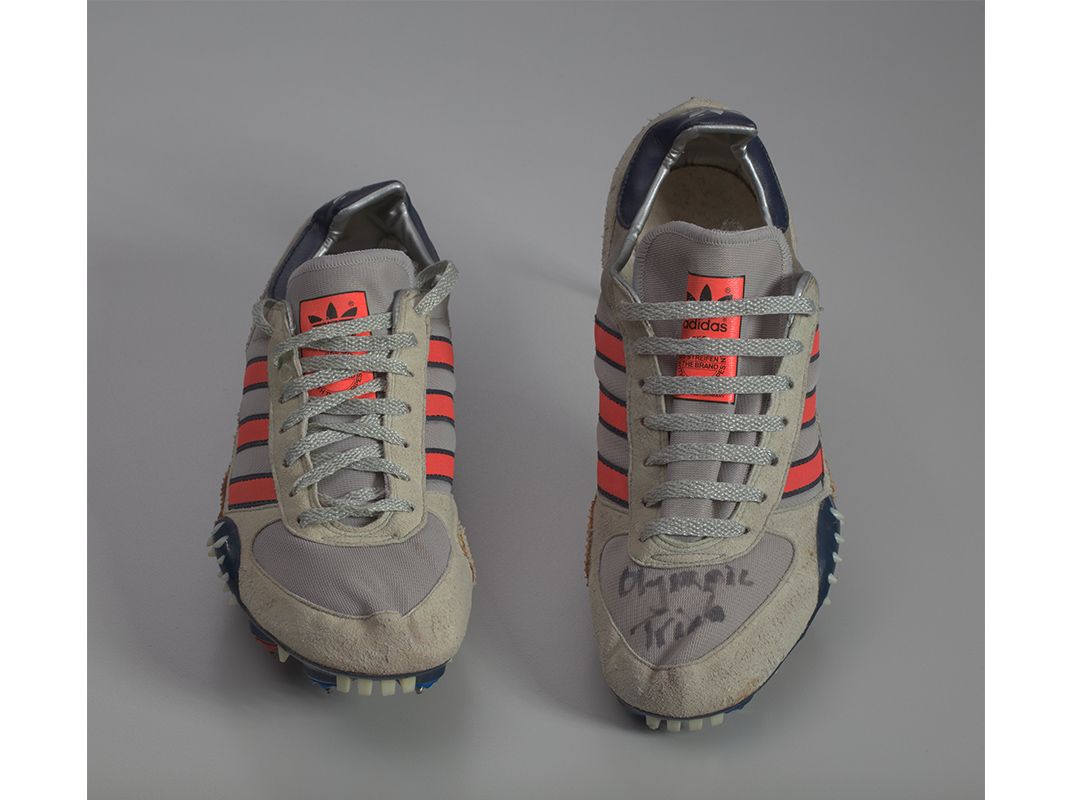

As a visitor walks down the stark, black and white displays, with colorful artifacts, pictures and stories about sports legends ranging from tennis legend Arthur Ashe (who won three Grand Slam titles), they pass a statue of the iconic Williams sisters. People stand between Venus (seven Grand Slam titles) and Serena (22 Grand Slam titles) smiling, and posing for pictures with these women who changed the face of the sport forever. There’s a display for boxing heavyweight Joe Frazier, and for track Olympians Jesse Owens and Wilma Rudolph.

Thomas is proud to be able to display a 1960 program from “Wilma Rudolph Day” that took place in her hometown of Clarksville, Tennessee, because it tells a very special story.

“This is an important artifact to have because Wilma Rudolph became the first woman to win three gold medals at the 1960 Olympics and she came back home and her home town wanted to host a banquet and parade in her honor but they wanted it to be segregated . . . Wilma refused,” Thomas says. “So what we have here is Wilma Rudolph refusing to cower in the face of segregation and demanding that African-Americans be treated equally on her day. This is the first integrated event in her home town and that’s the power of athletes to push social boundaries and advocate for social change.”

The sports gallery begins with statues of three other athletes that stepped into the face of history. Olympian gold medalist Tommie Smith and bronze medalist John Carlos stand with their fists raised, in what Smith describes as “a cry for freedom,” as silver medalist Peter Norman stood proudly by in a tableau that rocked the world in 1968. Thomas says this current moment in history is a time when athletes are making their voices heard.

“When there is a larger social movement, when the masses of people are actively engaged as they are with the Black Lives Matter movement, athletes understand that they have a role to play, and that role is often to be in many ways a town crier,” Thomas says. “Athletes have the ability to bring a conversation to the mainstream and certainly people who were unaware of some of the social injustices pay attention when (Knicks basketball player) Derrick Rose wears an ‘I Can’t Breathe’ shirt, or when players from the St. Louis Rams raised their hands in a ‘Hands Up Don’t Shoot’ protest or when someone like (San Francisco 49ers quarterback) Colin Kaepernick decides to sit down to protest racial injustice.”

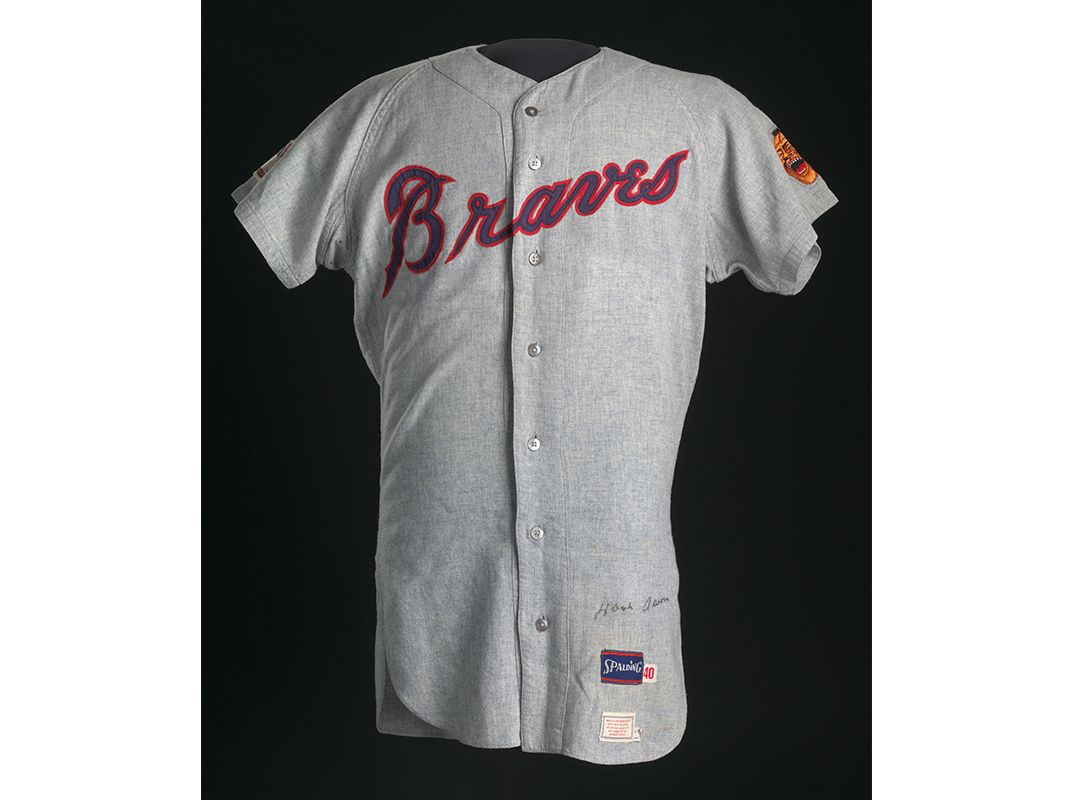

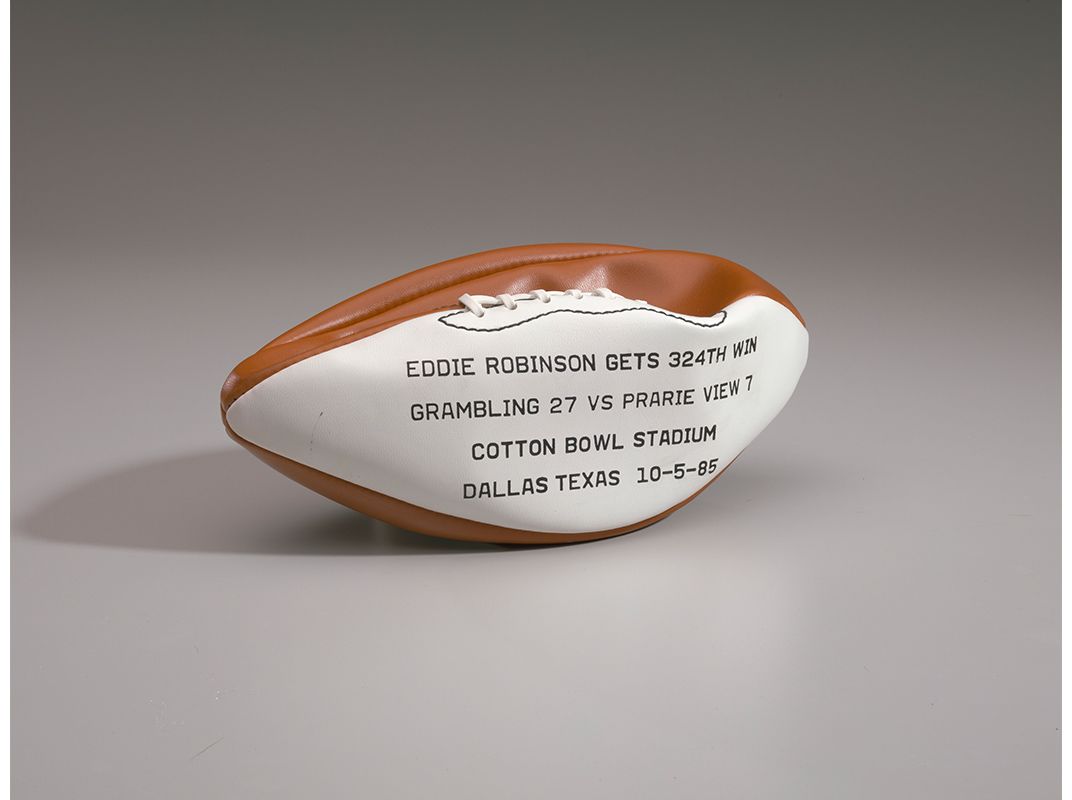

The sports gallery also commemorates many athletes who were pioneers in their discipline, with artifacts such as a game ball from the first football game with Art Shell coaching the Los Angeles Raiders on October 9, 1989. He is the first African-American coach for the National Football League since 1925.

“It is an important moment because when you think about the time between when an African-American first played in the NBA to the first African-American coach, 1950 to 1966, 16 years,” says Thomas. “Jackie Robinson integrated baseball in 1947. Frank Robinson becomes the first manager in 1974. That’s 27 years. But in football, the first African-American players reintegrate the league in 1947, but it’s not until 1989 that we get an African-American coach—43 years, four generation of players.”

Thomas says the question of why it took so long, is a complicated one.

“One of the great things we can do at this museum is ask those questions and think about the larger significance of sports and African-Americans getting the opportunity to compete and lead and be managers at the highest levels,” says Thomas, explaining why the football is one of his favorite objects. “It reminds us that sports weren’t always at the forefront of racial advance, and that’s an important point to remember as well that sometimes sports leads society, and sometimes sports trails society. It’s not always progressive.”

Jackson says that the fact that the nation’s first African-American president, Barack Obama, dedicated the museum sent a message to all Americans.

“We’ve come from slave ship to championship. . . . We brought light to this country, . . . (but) there’s unfinished business,” Jackson says. “We were enslaved longer than we have been free. So we are still in the morning of our struggle.”

"Sports: Leveling the Playing Field" is a new inaugural exhibition on view in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Timed-entry passes are now available at the museum's website or by calling ETIX Customer Support Center at (866) 297-4020. Timed passes are required for entry to the museum and will continue to be required indefinitely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/b6/41b6256d-3780-46e5-ad9b-355ecce5caee/2015_231_2_1-2_001-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)