With a New Name and New Look, the Cooper Hewitt is Primed for a Grand Reopening

Journalists got a sneak preview of what’s coming up when the new museum opens its doors this coming December

The Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York City won’t reopen to the public until December 12, precisely 112 years after steel magnate Andrew Carnegie moved into the 64-room Georgian brick mansion. But recently, more than 100 journalists gathered to hear Caroline Baumann, the enthusiastic director, make a presentation in the palatial estate that today houses a diverse collection spanning 30 centuries of historic and contemporary design.

Baumann was speaking in a 6,000-square-foot, pristine white gallery on the third floor, where Carnegie liked to practice his golf putting.“We are the only national museum devoted to the creative process,” said Baumann. “Going forward, we will be a place of experimentation, positive change and a place to explain design and bring the design process to life.”

What does that mean? Well, here is the best example: the museum’s new digital “pen.” A year in a half in the making by GE, Undercurrent and Sistelnetworks, after an initial concept from Local Projects with Manhattan architecture superstars Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the pen is what Baumann calls “a tool for a transformative visitor experience.” The digital stylus (the prototype we saw looked like a fat black cigar) gives new meaning to how you interact with the world around you. Like so much new consumer technology, the pen is based on the concept of “point... then click.” It seems to share the interactive zeitgeist of the new Amazon Fire phone.

“The pen cues you to a ‘collect feature’ so you can record an object from its label and store the data in the pen’s onboard memory,” said Jordan Husney of Undercurrent, a firm that works with the museum to transform how it connects with visitors. “First you record your favorites, then go to an interactive ultra-high-definition touch table where all your picks spill out. You can play with them and also explore related objects in the museum’s collection, learn about the designers and watch videos. Finally, you can upload the whole experience and transfer it to your computer at home.”

You are given the pen upon entering the museum. Even though you must return it before exiting, you will be able to access all the information you collected. The pen is paired with the entrance ticket, so you can log on to the online record you created later on at home. Best of all, when you return to the museum for your next visit, the pen “knows” what you have already collected. It accumulates knowledge. “‘How do you take the museum home with you?’ is what we asked ourselves,” says Husney. “How do you make museum boundaries more permeable?”

Baumann also introduced the “Immersion Room,” a high-tech space on the second floor where you can digitally access the museum’s vast wallpaper collection. You can either choose specific vintage wallpaper from the archive or draw one of your own design and project it, full-scale like real wallpaper, on two walls of the room. “This gives you the opportunity to play designer, to engage in the process of design yourself,” explains Baumann. “The idea is to make design fun and immersive.” Only one person can use the room at a time, so Baumann expects there will be lines of people waiting for access.

Finally, in the paneled room facing Fifth Avenue, the shop's former site, the museum has installed an interactive “Process Lab” designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro that in the words of longtime curator Ellen Lupton, is all about “drawing and sketching, making and doing. It’s hands-on, but high-level.”

“It’s a space about the design process, a design lab,” says Baumann. “It’s a family-friendly, digitally active space that emphasizes how design is a way of thinking, planning and problem solving. It provides a foundation for the rest of the design concepts on view in the museum.”

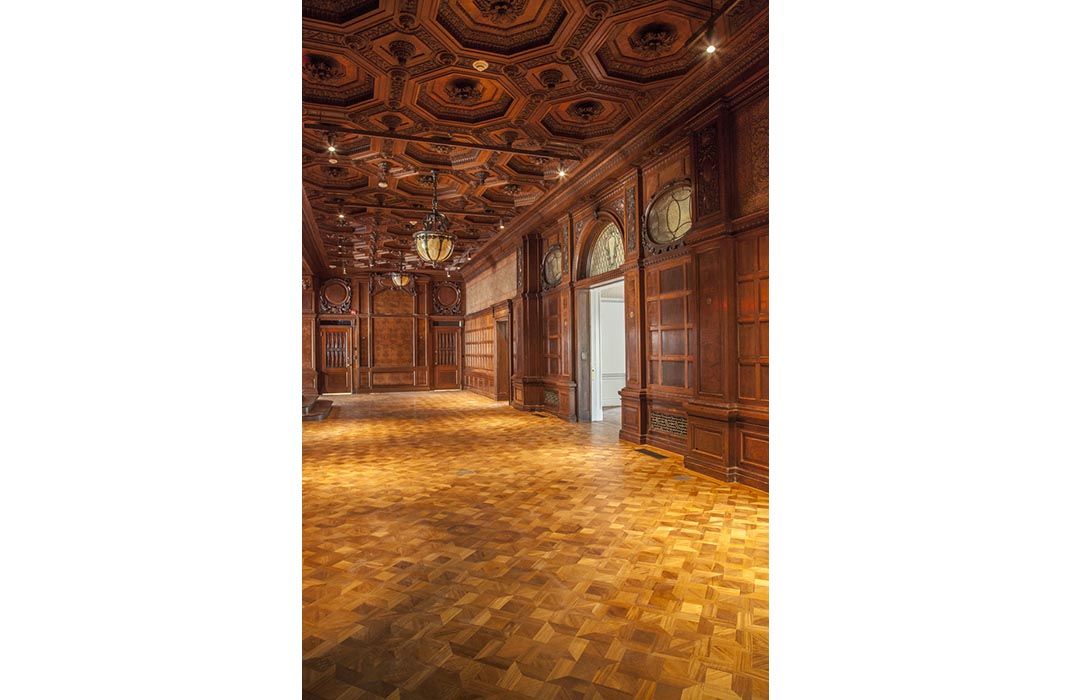

New York architects Gluckman Mayner and Beyer Blinder Belle did the three-year renovation of the museum, and their work is seamless. They have only enhanced the grandeur of the mansion designed by Babb, Cook & Willard in 1902—the first private residence in America with a structural steel frame, and one of the first with an Otis elevator. The exterior masonry and wrought-iron fence were cleaned and repaired. A dozen layers of paint were removed from the 91st Street foyer to reveal the original Caen stone. All the wood paneling and intricate original Caldwell electric light fixtures were cleaned and restored.

Of course, most of what has been done is invisible: the new mechanical/electrical/ plumbing systems, new security and data infrastructure, air conditioning and fire protection. A large, new freight elevator has been installed behind the paneling in the Great Hall, whose easternmost wall was moved back 14 feet. “We were required to keep the original Carnegie millwork, so we attached it to a new wall that rotates open to move large design objects in and out of the freight elevator,” says David Mayner of Gluckman Mayner Architects, who served as the project's design architect. “The wall weighs 2,000 pounds!”

The architects also pushed all the visitor services to the east: the shop, café, elevator, a new stairwell and entry to the garden. Because the staff offices and design library were moved to the museum’s townhouses at 9 East 90th Street, the mansion will now have 17,000 square feet of exhibition space, a 60 percent increase. “We no longer have to close galleries to mount special shows,” says Baumann. “For the first time, we have exhibition spaces appropriate for museum exhibitions.”

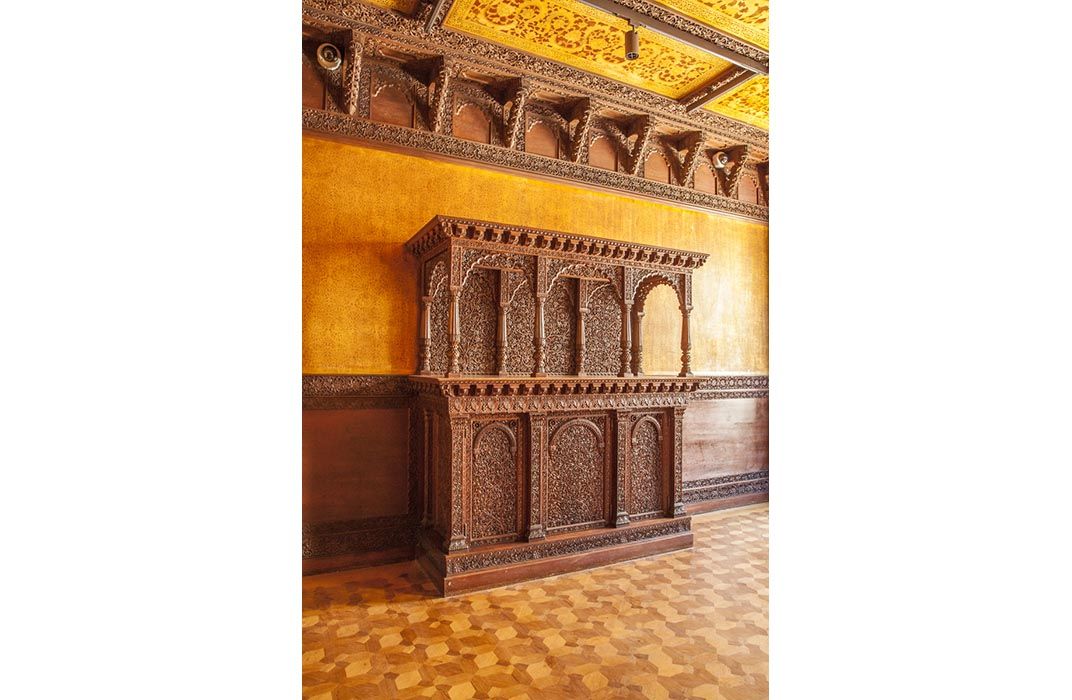

By converting office space, the second-floor galleries have been expanded to provide, for the first time, a display of some 700 objects in the permanent collection (selected from about 250,000 from around the world, which represent some 2,400 years of design). Howard Russell Butler (1856-1934) was the New York artist who designed most of the original interiors for Carnegie. Each of the grand public rooms is distinctive, from the wood linen paneling in Great Hall, to the pale wood-filigree ceiling in the Fifth Avenue room, to the Versailles-inspired gilded white paneling in the music room. Butler studied painting with Frederic Edwin Church and seems to have done many projects with Carnegie before they had a falling out in 1905. Carnegie then hired the fashionable New York decorator Lockwood de Forest to design the family library, now known as the Teak Room, which is the only intact de Forest room in existence.

De Forest was from a prominent family (he also studied painting with Church, a relative who became his mentor). In his 20s, he became interested in decoration after visiting Church’s mock-Persian-style Hudson River home, Olana. In 1879 he partnered with Louis Comfort Tiffany in forming Associated Artists, a decorating firm at the forefront of the American Aesthetic Movement, focusing on exotic design, handcrafted work and multi-layered, textured interiors. The same year, he married a DuPont. They honeymooned in British India, where he co-founded the Ahmadabad Woodcarving Company to supply hand-carved architectural elements. The elaborate openwork floral screens and mantle in the Teak Room are Indian, and the walls are stenciled in the Indian style. (The museum got a grant from American Express to have the panels cleaned with Q-Tips, a three-year process. And appropriately enough, with the largest collection of Church drawings in the world, it also plans to present Church drawings and oil sketches in the room.)

The Cooper Hewitt was founded in 1897 by Amy, Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, Peter Cooper’s granddaughters, as part of the Cooper Union School. “They based it on the Musée des Art Decoratifs in Paris,” said Gail Davidson, the longtime curator of drawings. “The sisters were keen on women’s education. They were concerned about women who were orphaned or divorced. They saw the museum as accompaniment to a women’s art school, so women could have careers.” It only seems appropriate that the director and most of the curators today are women.

Other announcements from the museum:

- Diller Scofidio has designed a new, second entrance to the museum on 90th Street. Beginning at 8 a.m., visitors will be able to access the garden and the café for free, without buying a ticket to the museum. California-based Hood Design is reinterpreting the 1901 Richard Schermerhorn, Jr. garden and terrace, the jewel of the museum.

- The museum has also changed its name to emphasize its heritage; it’s now the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

- And it has a new typeface, Cooper Hewitt, designed by Chester Jenkins of Village. The font can be downloaded free of charge on the website.

Now if they could share the technology of the pen, and make that open source, they would have engineers the world over experimenting with that technology and, surely, improve it. That would truly bring the world to the museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)