History Grabs the Headlines, But the Quiet Authority of the Art Gallery in the New Smithsonian Museum Speaks Volumes

In the visual arts exhibition the tone and the ambience suddenly shift

Entering the shiny new lobby of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, one might think it a brilliant showcase for contemporary art.

Across the ceiling sprawls an abstract bronze, copper and brass sculpture by Chicago’s Richard Hunt. On one wall is a five-paneled work from D.C. color field artist Sam Gilliam. On another, a relief of recycled tires from Chakaia Booker, who wowed Washington last year with an installation at the splashy reopening of the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

All of this inside a striking, critically-lauded building, designed by David Adjaye and his team, with its three-tiered corona shape, covered by panels inspired by ironwork railings made by enslaved craftsmen in New Orleans and Charleston, South Carolina.

Artistic as that might be, the bulk of the $540 million, 400,000-square-foot museum is given to the history of African-Americans, presented in four underground galleries. Two of the five aboveground floors are given to cultural and community milestones in sports, music and military, among others.

But once one walks into the Visual Arts Gallery, the tone shifts.

No longer dense with information, archival pictures and text, the gallery's uncluttered walls make way for splashy art that has space to breathe and have an impact. Not as flashy as the nearby, packed Musical Crossroads exhibition, it has a quiet authority, needing not to make a case for African-Americans in art, but merely putting it on display.

The first object to catch the eye upon entrance is Jefferson Pinder’s striking 2009 Mothership (capsule), which calls out to both the Parliament/Funkadelic Mothership replica in the nearby gallery—and the original Mercury capsules at the other end of the National Mall, in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

More than that, the replica of the Mercury capsule connects with the weight of history elsewhere in the museum as it is built with salvaged wood from the platform of President Obama’s first inaugural. (All that and it has a soundtrack: Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City” and Sun Ra’s “Space is the Place”).

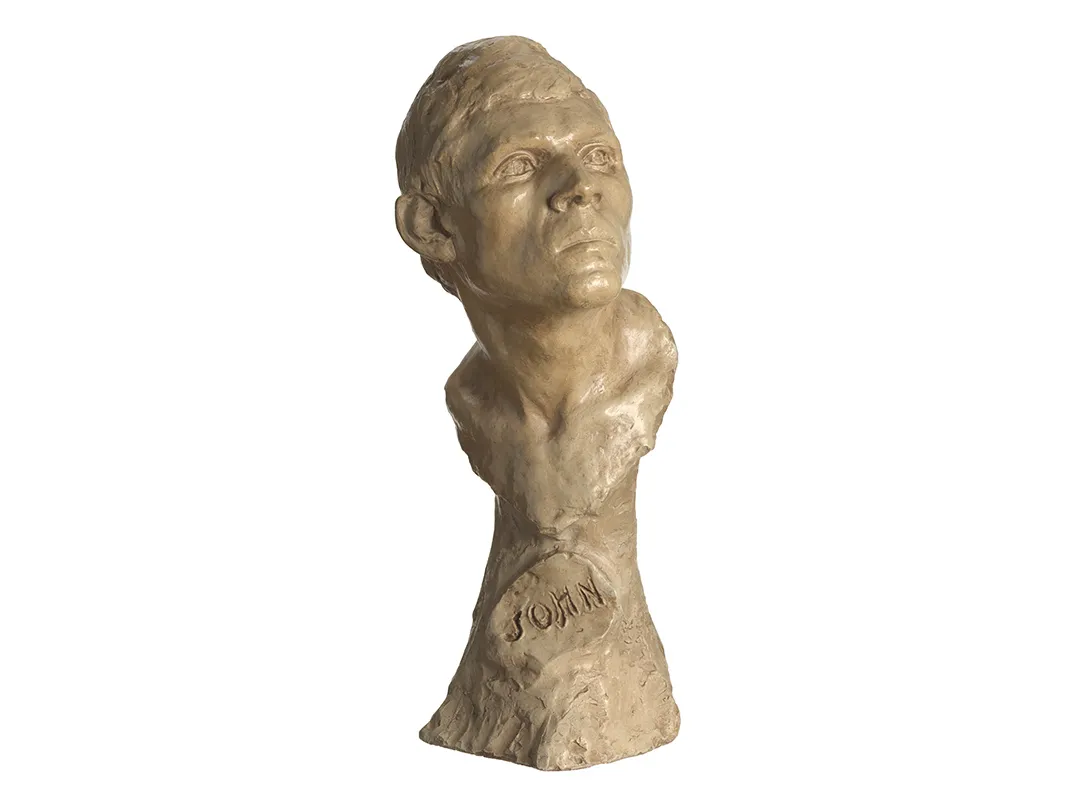

Several prominent African-American artists are represented in the exhibition, from Rodin-protégé Meta Vaux Warrick’s painted plaster 1921 sculpture Ethiopia to Charles Alston's 1970 bust of the Rev. Martin Luther King, jr.

Two paintings by Jacob Lawrence span two decades. There’s a vivid abstract from Romare Bearden, and an example from the influential David Driskell. His striking Behold Thy Son portrays Emmitt Till’s mother presenting the body of her lynched son. Till’s actual casket is one of the more powerful artifacts in the history museum five floors below.

The artist Lorna Simpson is represented by an untitled 1989 silver print also known as A lie is not a shelter, one of several aphorisms printed on a T-shirt around some folded black arms (among the others, “discrimination is not protection” and “isolation is not a remedy”)

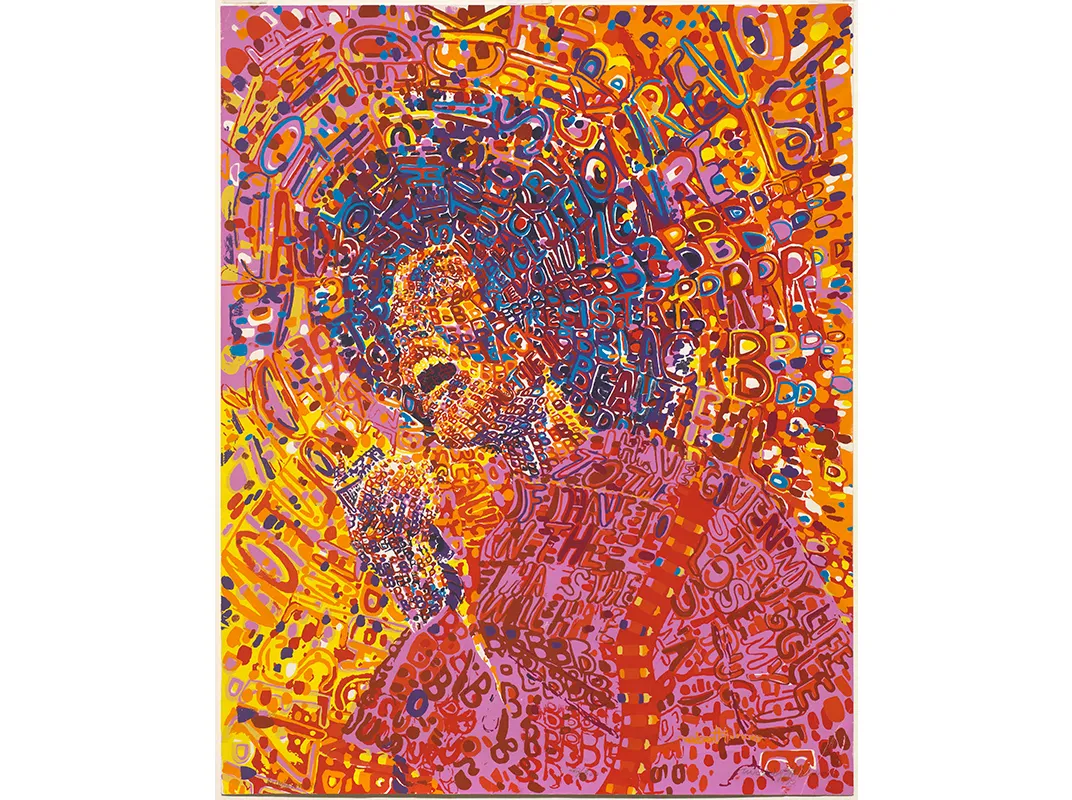

Activist art is a big part of the work in the gallery, with work drawn from a half century ago to current times reflecting the kind of uprisings chronicled in other corners of the museum.

Betye Saar’s mixed-media tryptich Let Me Entertain You from 1972 shows the transition of a 19th-century banjo-playing minstrel performer, seen in a second image is imposed over a photograph of a lynching, to the same figure in 20th century brandishing a rifle instead.

Barbara Jones-Hogu’s bold 1971 Unite shows a series of figures, fists aloft—like the life-sized statue of John Carlos and Tommie Smith lifting gloved fists when taking medals at the 1968 Olympics, in the sports gallery.

Even the most abstract works, such as a 1969 painting by Gilliam, whose commissioned artwork is also in the lobby, often make reference to key dates in African-American history. His April 4 denotes the day Martin Luther King was assassinated.

Simple funding may have prevented the gallery from having perhaps the best known of African-American artists—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kehinde Wiley, Martin Puryear, Glenn Ligon or Carrie Mae Weems, which sell in today’s market for breathtaking amounts of money.

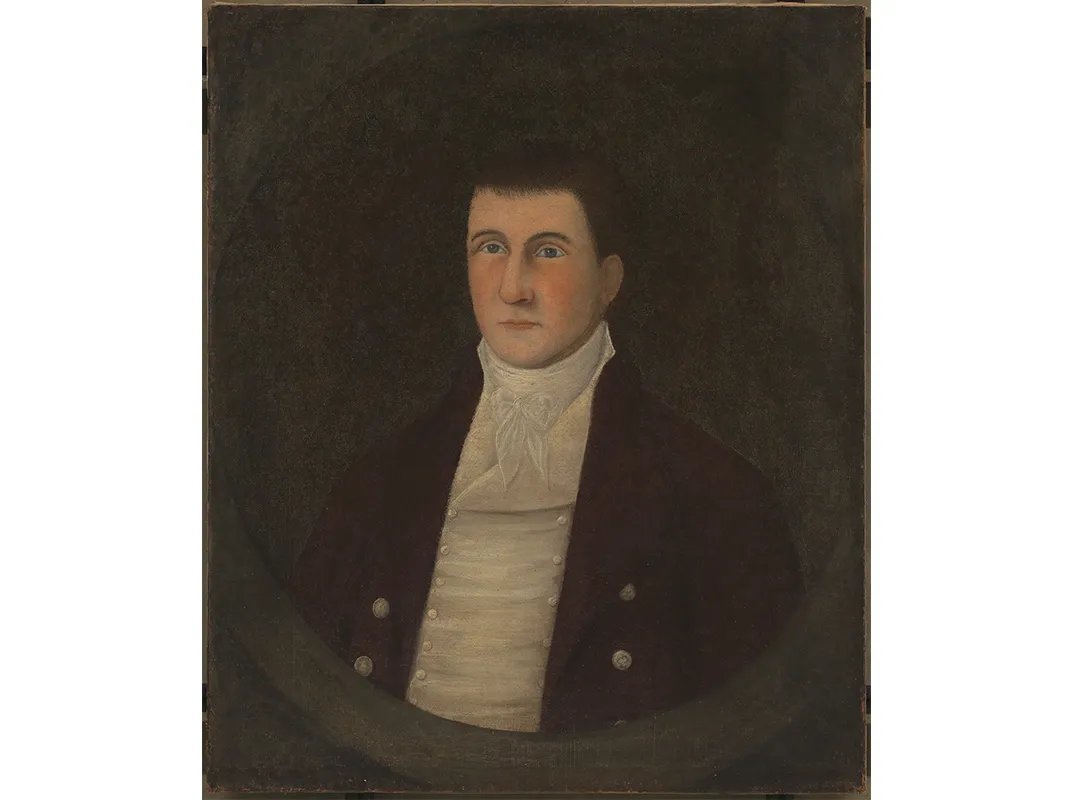

Still, there are lessons to be learned, particularly in some of the oldest pieces from artists who worked obscurely in their day, dating back to Joshua Johnson, a portrait painter in Baltimore thought to be the first person of color making his living as a painter in the U.S. He is represented by his 1807-08 work, Portrait of John Westwood, a stagecoach manufacturer whose children he also painted (The Westwood Children currently hangs nearby at the National Gallery of Art).

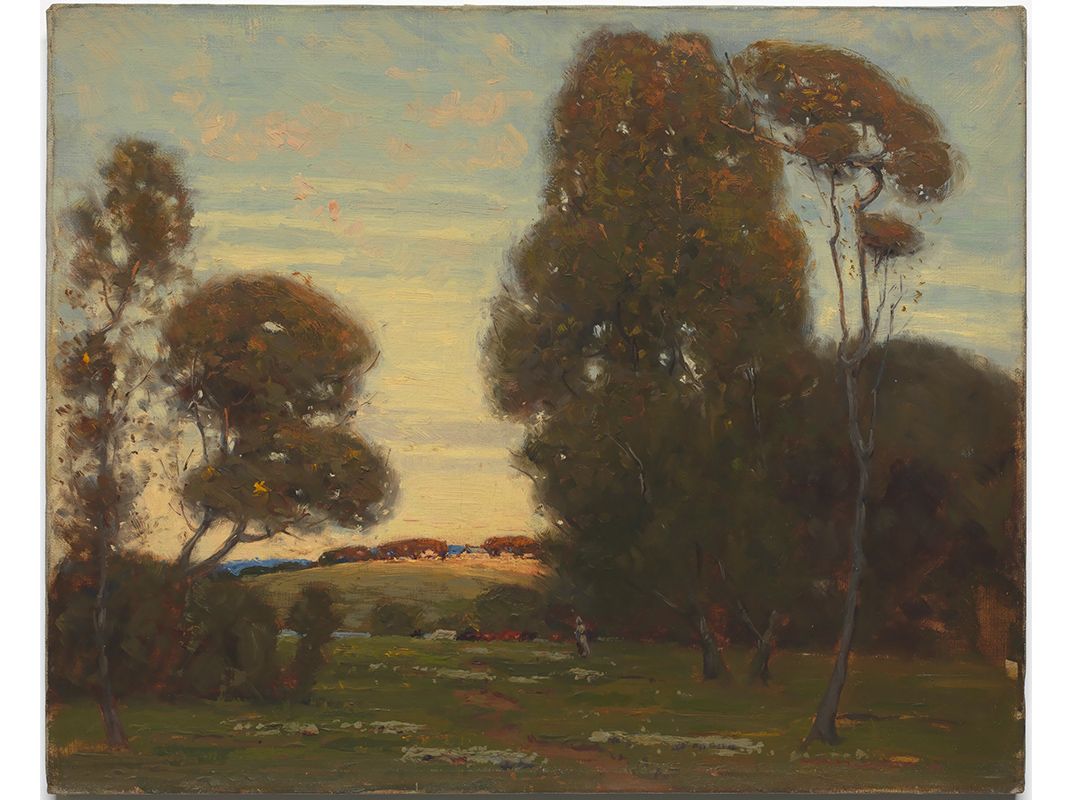

There was also Robert S. Duncanson, an African-American painter associated with the Hudson River School, whose 1856 Robbing the Eagles Nest is on display.

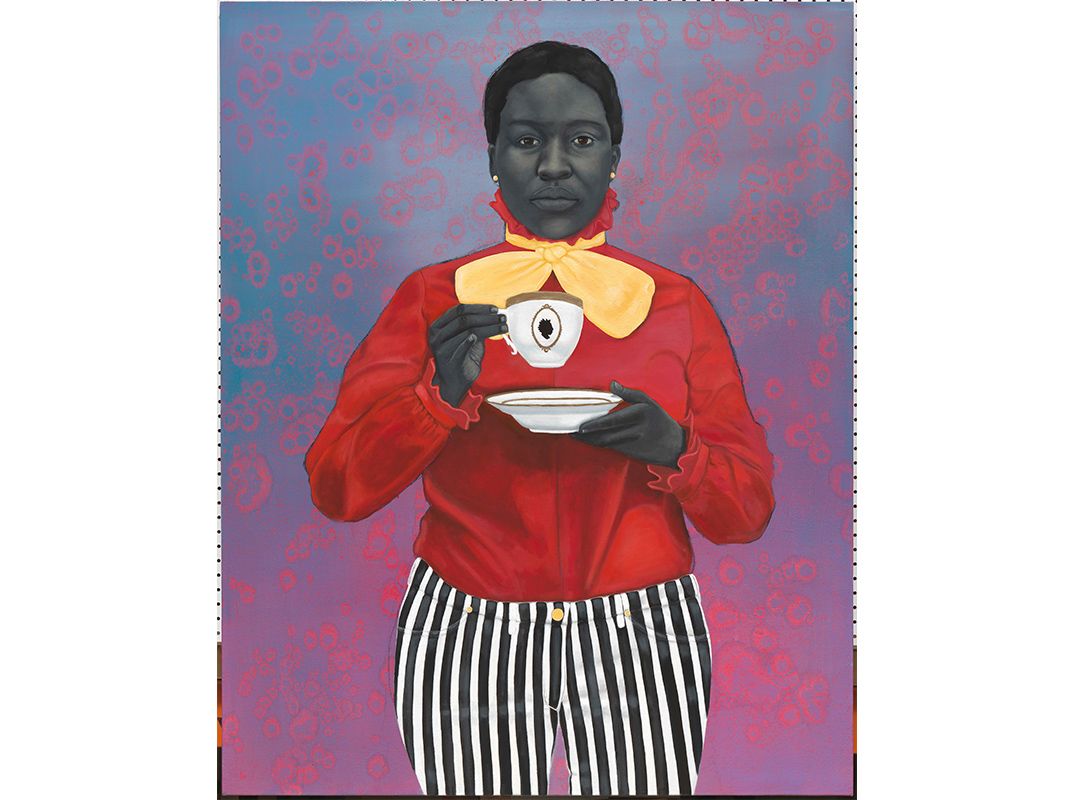

The Harlem Renaissance artist Laura Wheeler Waring, who was included in the country’s first exhibition of African-American art in 1927, is represented by a perfectly engaging 1935 portrait Girl in a Red Dress.

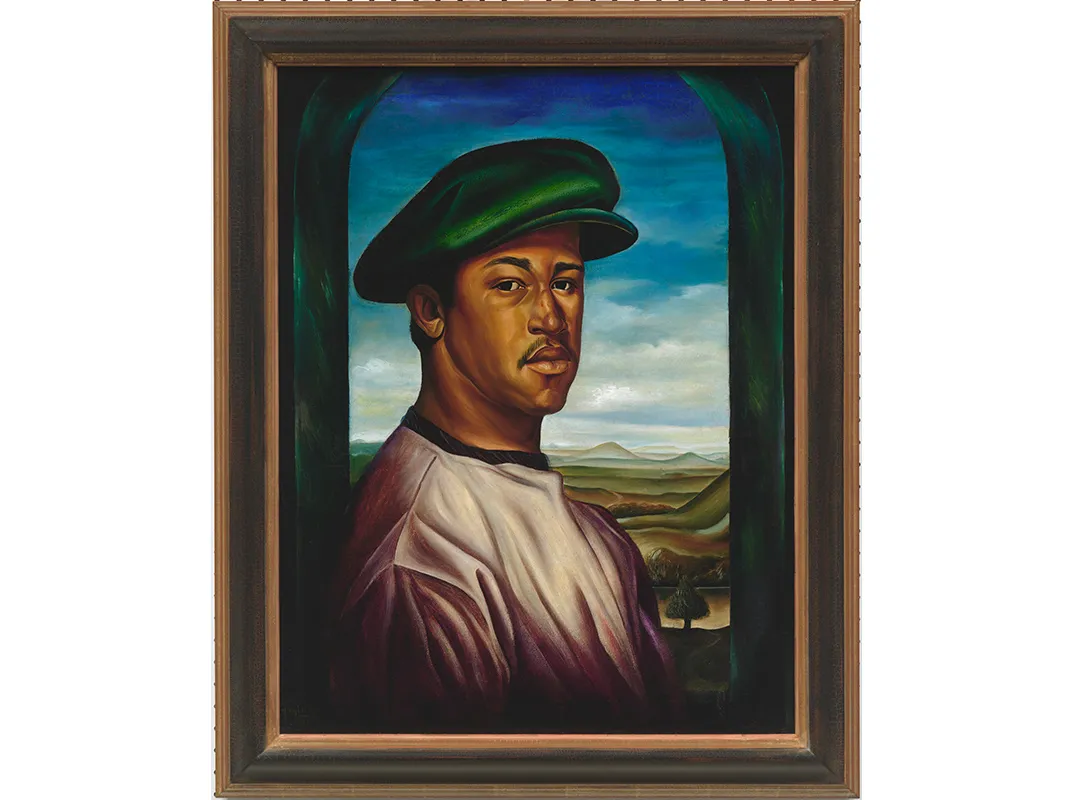

Several artists are represented by self-portraits, including Howard University educator James A. Porter, in studio work from 1935; Frederick Flemister’s Rennaisance-like painting from 1941; Earle W. Richardson’s piercing and haunting self-portrait from 1934 donated by family; and Jack Whitten’s jarring, mixed media 1989 abstract.

One of the most striking works in the gallery is Whitfield Lovell’s collection of 54 charcoal portraits with playing cards, Round Card Series, 2006-11 that takes up a whole wall (with each portrait paired with a card from the deck, including jokers).

Both a reflection of African-Americans and a strong survey of artists past and present, the Visual Arts Gallery plans to devote at least one part of it to changing exhibitions, in an attempt to showcase the myriad talent in a field that cannot afford, like much of the rest of museum, to be fixed for a decade.

"Visual Art and the American Experience" is a new inaugural exhibition on view in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Timed-entry passes are now available at the museum's website or by calling ETIX Customer Support Center at (866) 297-4020. Timed passes are required for entry to the museum and will continue to be required indefinitely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/c9/2dc9a054-7551-43b9-830d-6dfaef55ba7d/2013_242_1_001-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/e0/70e0f8d4-7fd0-4b08-a17e-32d44a927c12/2012_161ab_002.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)