New Works by Nam June Paik Are Discovered at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

While inventorying the massive archival materials left by the artist, a researcher comes across forgotten works of art

:focal(408x387:409x388)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/47/b747f875-f222-4203-bc7c-251418036ef4/01_paik_etude1web.jpg)

Since the Smithsonian American Art Museum acquired the Nam June Paik archive in 2009, the museum's researchers have delighted in cataloging the whimsical and diverse materials accumulated by the playful father of video art: reams of papers plus a cornucopia of objects: TV sets, birdcages, toys and robots.

Two of the more amazing finds—a silent new opera written in computer code from 1967 and a previously unknown Paik TV Clock—will make their first public appearance in "Watch This! Revelations in Media Art," an exhibition that opens on April 24.

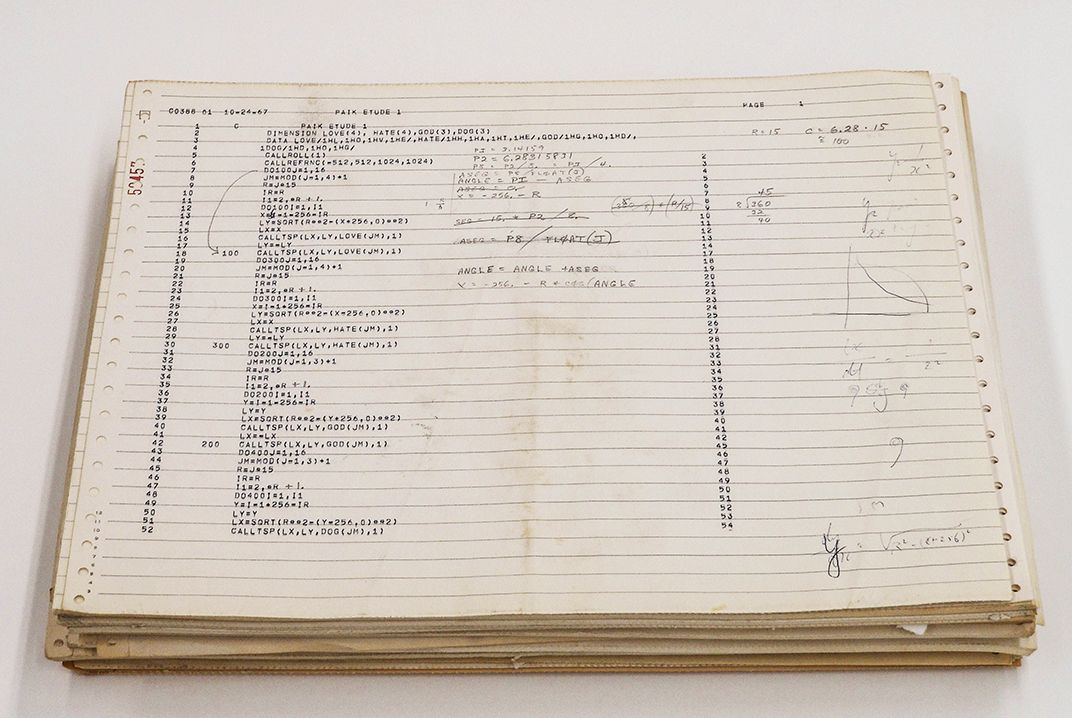

Michael Mansfield, curator of film and media arts at the museum, says that former-Smithsonian post-doctoral fellow Gregory Zinman (currently a professor at Georgia Tech), found the truly history-making original computer opera that was created in 1967 at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, then the research unit for AT&T’s Bell System in Murray Hill, New Jersey. “Bells went off when Greg saw a sheet of Fortran code and realized it was done at Bell Labs,” Mansfield says. “There were a very limited number of artworks that came out of Bell Labs.”

Titled Etude 1, the unfinished work includes a piece of fax paper with an image on it and an accordion-folded, pencil-annotated printout of Fortran code dated Oct. 24, 1967.

Nam June Paik (1932-2006), the Korean-born composer, performance artist, painter, pianist and writer is the acknowledged grandfather of video art. A seminal figure in the avant-garde in Europe and America in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, Paik transformed video into a medium for art—manipulating it, experimenting with it, playing with it—thereby inspiring generations of future video artists. Paik has already been the subject of museum retrospectives at the Whitney (1982), the Guggenheim (2000) and the Smithsonian (2013), but the discovery of his computer opera charts new territory in the intersection of art and technology.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/7a/347a8ce2-7420-43d7-a13e-25a5b33e5706/aahn001056web.jpg)

Paik’s intent was clear.

“It is my ambition to compose the first computer-opera in music history,” Paik wrote to the director of arts programming at Rockefeller University, seeking a grant, in the mid-1960s. He even mentions a GE-600, a “mammoth” room-size, new computer, at Bell Labs.

But how did Paik get to Bell Labs, the most top-secret, innovative scientific organization in the world at that time? Bell Labs are not known for art, but for innovations in transistors, lasers, solar cells, digital computers, fiber optics, cellular telephony and countless other fields (its scientists have won seven Nobel Prizes). That is a tale it has taken some time to unravel.

In the 1960s Bell’s senior management briefly opened the labs to a few artists, inviting them to use the computer facilities. Jon Gertner touches on this in his excellent book, The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation (Penguin Books, 2012), but he doesn’t focus on the artists, including the 1960s animator Stan VanDerBeek, Jean Tinguely, the musician Leopold Stokowski—and Paik.

“The engineers turned to artists to see if the artists would understand the technology in new ways that the engineers could learn from,” Zinman explains. “To me, that moment, that confluence of art and engineering, was the genesis of the contemporary media-scape.”

Etude 1 is the needle in the haystack of the Smithsonian’s Paik archive, a 2009 donation of seven truck loads of material donated by Ken Hakuta, Paik’s nephew and executor. It includes 55 linear feet of papers, videotapes, television sets, toys, robots, birdcages, musical instruments, sculptures, robots and one opera.

Etude 1 is one of three works that Paik created at Bell Labs and that are held in the museum's collections, Mansfield explains. Digital Experiment at Bell Labs is a short silent film that records what was happening on the screen of the cathode ray tube for four minutes as Paik ran his program through the computer. It is a series of rotating numbers and flashing white dots.

Confused Rain is a tiny snippet of film negative. Looking a bit like concrete poetry, the image is of seemingly random appearances of individual black letters of the word “confuse” falling like drops of rain against a plain white background.

Etude 1 is a piece of Thermo fax paper with an image that looks like a four-leaf clover, with four overlapping circles. Each circle has concentric inner circles composed of individual letters of the alphabet. The circle to the left is formed from the letters of the word “God.” The circle to the right, from the word “Dog.” The circle on top, from “Love,” the circle on the bottom, from “Hate.”

What does all this mean?

“It is completely open to interpretation,” Mansfield says. “I’m fascinated that Paik was using letters from the English alphabet to compose a visual work of art. He was aiming to put some human-ness into the machine. He was focused on the human use of technology. I think it corresponded to his need for a poetic alternative to the language of programming.”

Why “God, Dog, Love, Hate”?

“These are basic words with big concepts,” Mansfield says.

“I think it has to do with opposites, Paik’s play on words,” Zinman adds. “My guess is that he found that amusing. It also could be that short terms could be plotted more easily.”

The same words appear on the printout of Fortran code dated Oct. 24, 1967. An accompanying Bell Labs punch card, which allowed the computer to run the program, carries the name of a Bell Labs programmer, A. Michael Noll, the pioneer in algorithmic art and computer-animated film who monitored Paik’s visits.

As Noll, now professor emeritus of Communications at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California, recalls, “I was surprised when printouts with Paik’s name along with mine were discovered in the Smithsonian archive, though Paik’s visit to Bell Labs was the result of my visit, along with Max Mathews of Bell Labs, to Paik’s studio on Canal Street in New York.”

Mathews, who rose to become the head of the Bell Labs acoustic and behavioral research unit, was working on computer-generated music at the time and so knew of Paik, who had moved to New York from Germany in 1964 and was already an emerging performance artist.

“Mathews invited Paik to visit the lab and assigned him to me, but now, almost 50 years later, I do not recall much about what he might have done,” Noll says. “I gave him a short introduction to the Fortran programming language. He most likely then went off on his own, writing some programs to control the microfilm plotter to create images. The challenge back then was that programming required thinking in terms of algorithms and structure. Paik was more used to handwork.” He never saw what Paik did.

Still, Paik must have been excited about the new technology. Although it is not yet known how he physically got from the city to the labs in the New Jersey countryside, he visited every three or four days in the fall of 1967. Then, he started going less frequently.

“He was frustrated because it was just too slow and not intuitive enough,” Zinman says. “Paik moved very fast. He once said his fingers worked faster than any computer. He thought the computer would revolutionize media—and he was right—but he didn’t like it.”

Then he stopped going entirely.

“It put a real financial strain on him,” Mansfield says. “Paik was a working artist, selling works of art to live, and he was also purchasing his own technology. He was becoming distracted by his electronic artworks.”

Nonetheless, Paik’s work at Bell Labs was important.

“His idea was to take things apart,” Zinman says. “He was playful, interested in disrupting patterns. He wanted to rethink how media worked, just as he wanted TV to be a two-way communicative device, going back and forth. He was modeling a way for people to take control of the media, instead of being passive.”

Adds Noll: “Bell Telephone Laboratories was a tremendous place to allow such artists access. I am working on documentation of the battle between Bell Labs management and one individual at AT&T who objected to work in computer art and other areas that this one person deemed ‘ancillary.’ In the end, the most senior management—William O. Baker—decided to ignore AT&T and follow the challenge of A.G. Bell to ‘Leave the beaten track occasionally and dive into the woods.’”

Paik has never been more popular. There was recently a show of his work at the James Cohan gallery in New York; he was the subject of an entire booth at the recent Art Fair in New York and also appeared in a stand at the European Fine Art Fair this year in Maastricht, the Netherlands. His works are selling—and for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. It seems another generation is rediscovering the father of video art—and embracing him wholeheartedly.

Etude 1 along with the recently recovered TV Clock will debut in the exhibition Watch This! Revelations in Media Art, which opens at the Smithsonian American Art Museum April 24 and runs through September 7, 2015. The show includes works by Cory Arcangel, Hans Breder, Takeshi Murata, Bruce Nauman and Bill Viola, among dozens of others, and will include 16 mm films, computer-driven cinema, closed-circuit installations, digital animation and video games. Learn more about the museum's discovery of the art work on Eye Level, in the article "Computers and Art" by curator Michael Mansfield.

The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

Nam June Paik: Global Visionary

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)