Nine Days of a Sailor-Scholar’s Life Aboard the Canoe Circumnavigating the Globe

A Smithsonian expert learns the hard-knock lessons of when to be quiet and how to take a poop

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/66/d56613ca-4bff-447c-b39a-575b384c07d4/dawn_at_piscataway.jpg)

“Welcome to voyaging!” says Nā‘ālehu Anthony after a wave washed over the bow of the canoe and soaked the three of us. We are aboard Hōkūleʻa, the famous Hawaiian voyaging canoe that is going around the world, as it is being towed out of Yorktown, Virginia, and into the Chesapeake Bay.

Hōkūleʻa, which was recently honored by United Nations in recognition of its historic four-year journey to sail around the world, is raising consciousness about caring for Mother Earth. Since departing Hawaiian waters in May 2014, the craft has sailed more than 22,000 nautical miles, visited 13 countries and made stops at 60 ports. I am standing at the forward mast with Zane Havens, another newbie to Hōkūleʻa, and Nā‘ālehu, who at this moment is the captain, and we are literally learning the ropes—the daunting mass of coils and cleats involved in working the sail and the mast.

I have been granted the rare honor of crewing for a portion of this leg of the World Wide Voyage, and will be with the canoe for nine days as it makes its way to Washington, D.C. We will visit Tangier Island, Northern Neck Virginia, Piscataway, and this article along with my other dispatches will detail what we learned along the way.

But first there is the learning necessary to serve as crew: the straightforward lessons about how to work the canoe and how to live on the canoe, and the far more elusive learning of one’s place on the canoe.

My aim before we headed out to the high seas was to get ma‘a to the wa ‘a.

Ma‘a—(MAH-ah) means “accustomed, used to, knowing thoroughly, habituated, familiar, experienced,” and wa‘a (VAH-ah) is the Hawaiian version of the pan-Polynesian word for canoe.

I am also in the process of building a four-foot model of Hōkūleʻa, and these two processes feed each other: knowing the canoe will help me make the model accurate, and building the model will help me know the canoe better.

Hōkūleʻa is a “performance replica.” She is built to perform like a traditional canoe, but made of modern materials. The hulls are plywood and fiberglass, the rigging is Dacron. But in other ways, she is an intricate vessel compared to the Hikianalia, the larger and more modern-style canoe I trained on a few months ago. The sails are traditional crab-claw style, the rigging more complicated, the accommodations more…rustic, and on the whole, it is wetter.

When I first came aboard Hōkūleʻa in Yorktown, the coils of lines on the masts were daunting. It was hard to imagine I would ever know what all of these did. “Mau understood this canoe immediately,” I was told by master navigator Kālepa Baybayan, referring to his teacher Pius “Mau” Piailug, the famous navigator from the island of Satawal. “He just looked over all the rigging and understood right away.” But for someone with only a little experience on large sailing canoes, it would take longer.

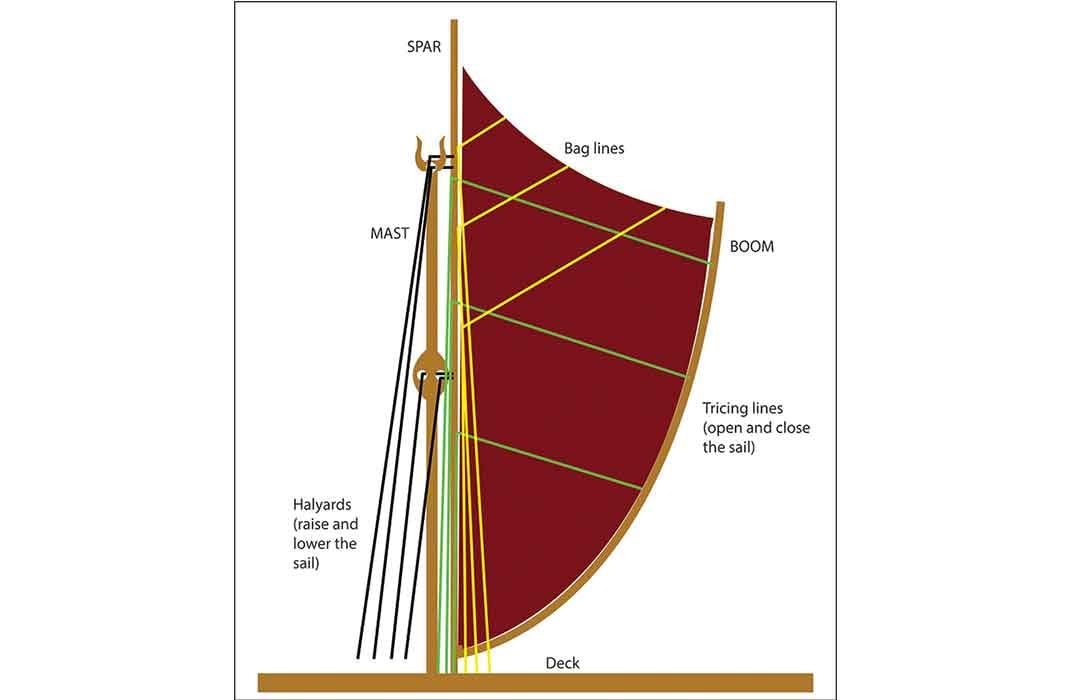

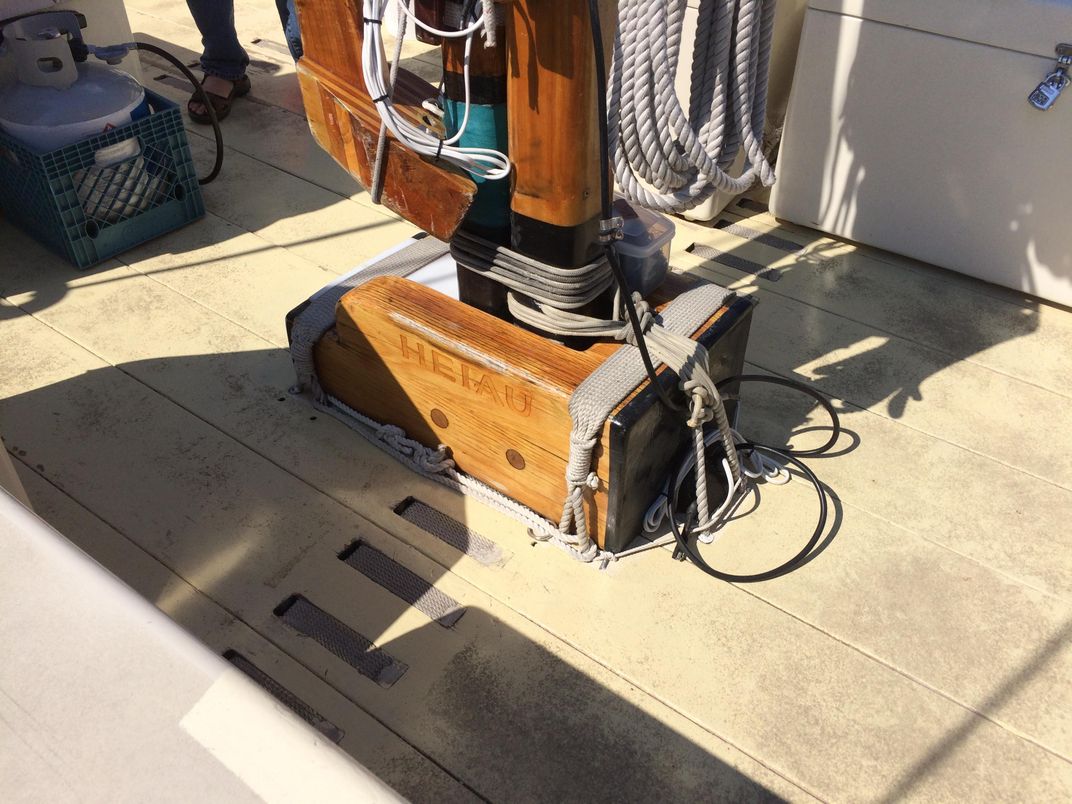

Hōkūleʻa has two masts—the main mast in front, and the mizzenmast in the center. Each is held in place by a large number of stays—ropes that pull the mast from enough different angles to keep it securely perpendicular to the deck. Unlike most modern sailboats, the masts rest in blocks on the deck. The sails are fastened to a spar—the piece that goes up against the mast—and a boom, which curves outward when the sail is open.

Our first task was to attach the sails to the spars and booms (why they were off in the first place I do not know). Each one is tied on loosely around the spar and boom with little strings, so that the sail can slide freely to attain its proper shape when the wind pushes against it. We had to be careful not to tie these strings around the many lines running up the spars, and several had to be redone.

Then the closed sail is hoisted up against the mast. This takes four people, one on each of four halyards, with some others on the deck lifting the sail until it is beyond their reach. Once the sail is up, the halyards are coiled in a certain way that allows them to be hung on cleats on the mast. This is true of all the lines used in the rigging. A simple loop in the cleated end can be lifted off and the entire coil dropped to the ground when the line needs to be used again.

Opening the sail involves loosening two sets of three tricing lines. These are attached to the boom and they let it out. One person gets on each set of these lines. In addition are what they called “bag lines.” These are attached to points along the top of the sail. When we close the sail, someone pulls on these first to help bundle up the sail nice and tight so that it doesn’t bag out. To open the sail, these need to be loosened.

Nā‘ālehu had us practice raising the sail, opening the sail, closing the sail, and lowering the sail several times until we were all familiar with the process. Of course, most of the crew were seasoned voyagers who had done multiple legs of the Worldwide Voyage already, but this was good practice nonetheless.

Much more complicated is the raising and lowering of the masts themselves. This we needed to do to get under the many bridges leading into Washington, D.C. In fact, we had to do it twice—once to get up to the Lincoln Memorial, where we then put everything back up and opened the sails for a photo shoot, and then down again to get under the next two low bridges; and then up for the final ride to the Washington Canoe Club.

This process would be easy if we could take down the mizzenmast first, but because there is not sufficient room out in front of the main mast to get a good angle on the rope, the main mast comes down first. It was necessary to put a block and tackle on the front stay, and use lines from the mizzenmast to help lower it down. Problem is, all the stays from the mizzenmast are in the way of lowering the main mast. So they had to be moved, one at a time, as the main mast came down. Plus, the whole process ran in reverse to put it back up. By the third run, we managed to do it all in an hour and a quarter—down two hours the first time. We also had recruited some tall fellows from the Washington Canoe Club to come aboard to help lift.

The other workings of the canoe were familiar to me already: the giant steering sweep—a huge, 18-foot paddle on a pivot that is used to steer the canoe; the workings of the tow line (we were towed the entire way by a separate boat, with the indefatigable Moani Heimuli at the helm.)

Life aboard Hōkūleʻa is rather like camping. Full crew is 14 people—12 crew, the captain and the navigator. Under normal conditions, we would be operating in two shifts, each doing stretches of four, five or six hours at a time as the captain sees fit. In this case, except when we were coming into port, there was little activity on board. Someone needed to be at the steering sweep at all times—sometimes two people, depending how rough it got. Each night we came into a port, where we had access to bathrooms, hot showers and cold drinks. In most places, we also had accommodations with real beds, walking distance from the canoe.

Towards the end, I preferred to sleep on the canoe. I had an assigned bunk that was just my size along the side of the canoe and I could roll back the canvas to watch the stars before drifting off.

Hōkūleʻa is brilliantly designed with a series of hatchways down into each hull, regularly spaced between the booms that hold the two hulls together. A guardrail around the deck has diagonal supports going out to the far edge of each hull. Canvas is stretched over these supports to create kind of a long tent. On the deck side, the zipper doors in the canvas hid the sleeping compartments atop the hatchway. The Hawaiian word “puka” was often used to refer to these. Puka means both “hole” and “doorway,” and so is particularly apt for these low places you crawl into.

Plywood boards have been placed over the hatches, and thick foam pads on top of those. I had puka #2 on the starboard side—the one closest to the bow (#1 being the entry way onto the canoe). My belongings were kept in a waterproof sea bag, with a few extra things stashed in a cooler alongside the hatchway under the plywood. A clothesline above the door allows you to hang things you need to access regularly—headlamp, hat, sunglasses and so forth. There are also some pockets for things like toiletries and sunscreen.

Inside the hatchways is storage, and the ship’s quartermaster has to keep track of what is stored under each puka. In mine there were a dozen waterproof boxes labeled “crackers” and a handful of five-gallon jugs of potable water. A water cooler was kept on deck and everyone had a water bottle with a carabiner on it so it could be clipped to a line when not in use.

When the cooler ran out, which happened a few times, I had to move all my gear into the next person’s bunk or out on deck, lift up the plywood and foam pad, remove the hatch cover, and climb down into the hull to lift out another five-gallon jug. This occurred often enough that I kept my puka pretty tidy, and it was used for demonstrations when we came into port.

Over the last two sleeping pukas on each side are the navigator’s platforms. This is where the navigator sits—on which ever side allows him or her to see past the sails. To the rear of these is an open puka on each side. On one side are the buckets for washing dishes: two with plain water for before-and-after rinsing, and one with soap for washing. All this was done in seawater, except coming up the Potomac where we were uncertain about the cleanliness of the water.

Cooking takes place on a two-burner propane stove on deck. It sits in a box with awnings at the sides to keep out the wind. Another box contains all the cooking gear and utensils. Breakfast and lunch were mostly a hodgepodge of snacks, cut-up oranges and other lite fare. Dinner, however, was a hot meal: something with noodles, often. And hot noodle dishes were also served for lunch on colder, rainier days. During real voyaging, there would be hot water going all day for tea, coffee or cocoa.

Everyone wants to know how you go to the bathroom on the canoe. First, if you are not already wearing a safety harness (and on this leg of the voyage, we almost never were) you have to put one on. Then you tell someone that you are going to the bathroom. It’s all about avoiding a man-overboard situation—nobody wants that. (I am told it has happened only three times in 40 years of voyaging on this canoe.)

Then you go out through that back puka, around the back of the navigator’s platform, and onto the catwalk on the outside edge of the hull. Here you clip a tether from your harness onto the safety rope that runs all the way around the outside of the canoe. If you fall off, at least you will be dragged along rather than left behind. Once you are secure, you hang your bare bottom out and do what needs to be done. When you return, you tell that same person that you are back. “Sometimes in rough conditions I’ll be talking to people as they go out,” says Mark Keala Kimura, “and I’ll keep talking to them while they go to the bathroom, just to make sure they’re still there.”

Back in 1976, it was even less private: “The rails are all open, there was no covering, so pretty much when you went you were in full view of everybody,” recalls veteran voyager Penny Rawlins Martin—“with your escort boat behind you!”

On this trip, two small shipboard toilets had been installed in the stern compartments, with canvas curtains that could be drawn. Going up the Intracoastal Waterway from Florida, it was thought to be poor form to have bare bottoms hanging over the side.

Plain to see on the back of the canoe is a giant plate of solar panels. There is no modern navigational equipment on Hōkūleʻa—not even a compass—but there does need to be power for lights at night, for radio communication with the tow boat, and for the triple-redundancy emergency systems. Safety first.

Overall, the crew is a family, but like any family, there is hierarchy on the canoe: the navigator, the captain, the watch captains, the apprentice navigators. Everyone on board has, in addition to regular crew duties, a particular kuleana—responsibility or skill, such as fisherman, carpenter, doctor, sail-repairer and so forth.

This time our crew contained three people from ‘Ōiwi TV, the only Hawaiian-language television station in the world, working on documenting the voyage with still and video cameras, including a drone. There were educators who ran programming when we were in port. And there was me, documenting the trip for the Smithsonian Institution.

I also consider myself an educator. A former university professor and now Smithsonian scholar, I’ve been teaching about Polynesian voyaging and migrations for 30 years. More recently, I’ve been writing and lecturing on traditional navigation, and the values of the voyaging canoe and what they tell us about how to live on this planet. I built and sail my own outrigger sailing canoe and have been both blogging and giving lecture and demonstrations about traditional canoe building. And I did do a training voyage in February on the Hikianalia.

So I arrived with a certain, tentative confidence, and when in port at educational activities, felt it my kuleana to share the lessons I have derived from so much research. But I quickly felt that something was not going well, and this feeling got stronger as the trip went on. Yes, we were not functioning like a normal crew, and as we were being towed, my inexperienced presence was really hardly necessary. These folks knew what to do and moved like clockwork when things needed to be done.

These were young, sea-hardened voyagers, some of whom were now on their fifth leg of the Worldwide Voyage (and legs take up to 40 days). I was simply not one of them.

What right did I have to talk about lessons of the voyaging canoe? I had never been on a real voyage. Finally someone pulled me aside and said “Brah, you are always saying the wrong thing at the wrong time.” There were also protocols I was breaking, of which I was not aware.

“You got to have thick skin and you’ve got to work your way up the ropes,” Kālepa had told me in an interview back in 2011. Learning to sail the canoe involves a lot of hard knocks.

Humbled, I realized, even before this calling out, that I needed to shut up. Enough talking about voyaging; now was the time to listen. I came on board thinking I was, well, someone—someone with a part in this. I realized that, for purposes of the canoe, I was no one. A total newbie. And once I realized that, a letting go feeling came over me, and I was happy. I now knew my place on the canoe, and it was good.

The next day, when we were docked in Alexandria and giving tours, I ran into Nā‘ālehu. “Hey ‘Lehu,” I said cheerfully, “I finally learned my place on the canoe.” “Oh really?” he responded with a smile. “Yes,” I said, “I guess everyone has to make that journey at some point.” He shook his head kindly and replied, “Some people just keep on sailing…” –and never arrived at that shore.

Now I am practicing my knots, building my strength, and continuing work on my Hōkūleʻa model—work that requires knowing all the ropes. I will be ma‘a to the wa‘a to the best of my ability, and someday, maybe I will get to go voyaging for real.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)