Oldest Cancer Case in Central America Discovered

A young teen, who died 700 years ago, likely suffered pain in the right arm as the tumor grew and expanded through the bone

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/dc/35dcd89b-e29e-407b-8449-8d2f238755f3/figure_5_1.jpg)

On a shelf in Panama City, a human skeleton was bundled into a bag within a cardboard box for 46 years. Or part of a skeleton, anyway. The bones had been looked at once in 1991 and then shelved again. Then one day Nicole Smith-Guzmán, a bioarchaeologist and a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) opened the box and noticed that there was something a little bit different about these bones. The humerus of one arm featured a lumpy calcified mass.

This turned out to be the oldest known case of cancer in Central America.

The bones had been excavated in the Panamanian province of Bocas del Toro in 1970 by the now-deceased archaeologist Olga Linares, who had set out to study the agricultural practices of people in the area.

“I think [Linares] did notice that something was off about this skeleton because she wrote in her 1980 manuscript that this was a diseased individual,” says Smith-Guzmán, “and that was why they were buried in a trash midden. But she didn't realize that the person was buried at a different time than when the site was occupied.”

Smith-Guzmán is the lead author of a new research paper describing what she believes is the oldest example of cancer ever found at a pre-Columbian site in Central America.

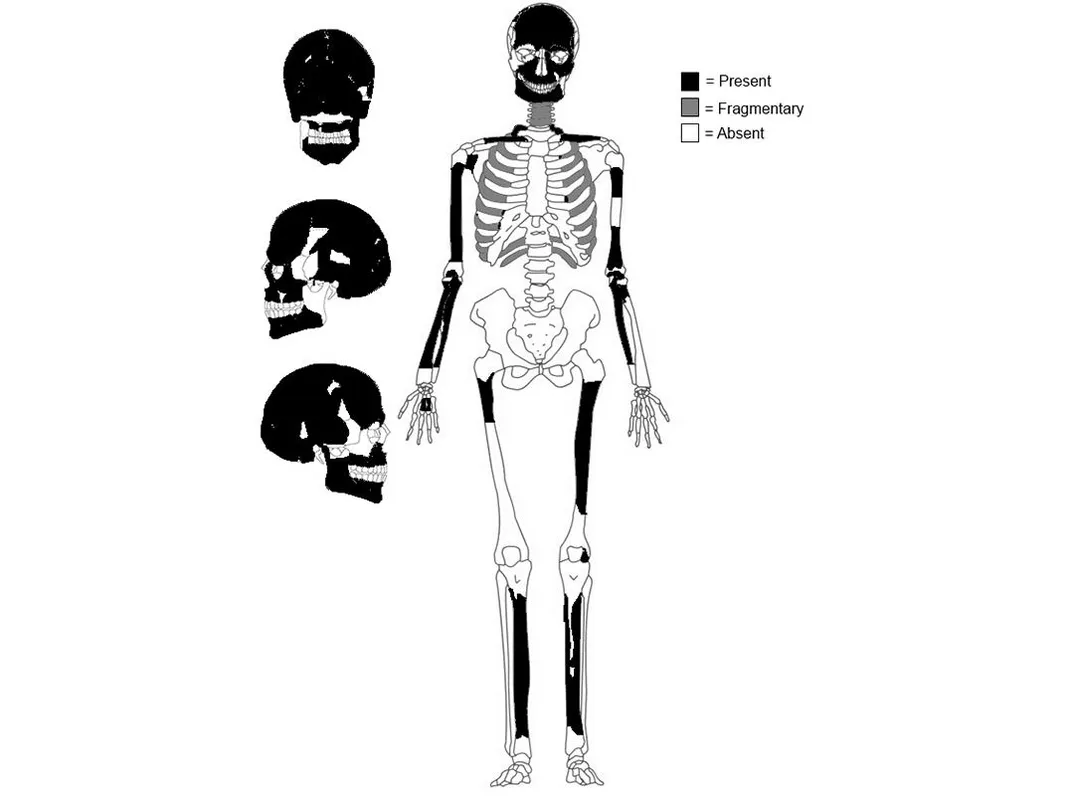

The bones belonged to a teenager who was probably between 14 and 16-years-old, based in part on the light wear of the teeth, absence of third molars and the degree of fusion between the bones that form the cranium. It was probably a female, but that is hard to say for certain without a pelvis and until DNA analysis comes back. Radiocarbon dating shows that she died about 700 years ago.

The exact type of cancer which afflicted the teenager is not known for certain, though it was certainly one of several types of sarcoma. It would have caused intermittent pain in the right arm as the tumor grew and expanded through the bone. “There would have been an associated soft tissue mass, creating a swollen appearance of the upper right arm,” according to the paper.

But the cancer probably wasn't the cause of death.

“We can never really determine cause of death in bioanthropology,” Smith-Guzmán says. “We might be able to suggest manner of death, but in this case I collaborated on this paper with a specialist in pediatric oncology, [Jeffrey Toretsky of Georgetown University]. And he doesn't think that this person would have died of the cancer.”

The bones were found at an abandoned village, carefully arranged in a midden, or mound of organic refuse, that had accumulated during the time people had lived there. Only two sets of human remains were uncovered at the burial site (though Linares also wrote that other disarticulated human bones were found throughout the refuse). Even though the burial took place in what amounts to a huge compost pile, Smith-Guzmán thinks that Linares was wrong about the deceased being thrown away like trash.

“We see that the people who buried them cared about this person,” Smith-Guzmán says. “This wasn't just discarding the body of a diseased person. We think this was a ritual burial. We can tell that the culture has a sort of ancestor veneration. As well as a care for diseased individuals. They obviously had to be taking care of this person for a while and buried them with these objects of ritual significance as well.”

The surviving objects buried with the body include several ceramic vessels and a trumpet made from the shell of an Atlantic triton.

Part of the reason why more ancient cases of cancer have not been found in Central America is the fact that the soil tends to be acidic. Rain also tends to be slightly acidic. Unless something special protects skeletal remains, the bones will eventually dissolve. This skeleton was partially protected by marine shells in the decayed refuse mound that the body was buried in. The lime of the shells adjusted the pH of the soil and water surrounding the bones, preserving them.

“There's no evidence that cancer was less common in the past,” says Smith-Guzmán. “The thing is that cancer is rare in people that are less than 50 years of age and if you think about skeletal remains that are going to be preserved and excavated, you have an even smaller sample size. That's why we don't see more cases of cancer described in ancient populations. Also you have to have a cancer that affects the skeletal remains, which is unusual.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)