Q+A with Chadwick Boseman, Star of New Jackie Robinson Biopic, ’42′

The actor talks about getting vetted by the baseball legend’s grandchildren, meeting with his wife and why baseball was actually his worst sport

![]()

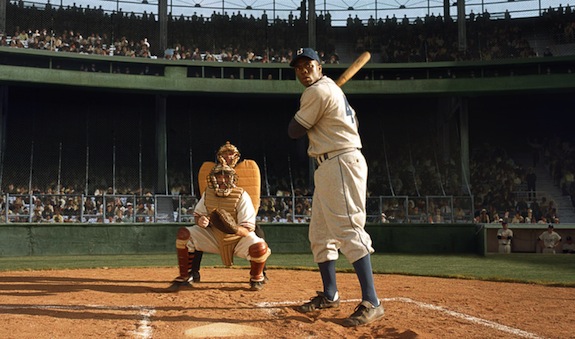

Chadwick Boseman as Jackie Robinson. Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment

In 1947, when Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers and broke major league baseball’s color barrier, the world was still 16 years away from the March on Washington and the Civil Rights Movement as just getting organized. The Montgomery bus boycott was eight years away and housing discrimination based on race would remain legal until 1968. In his first season with the MLB, Robinson would win the league’s Rookie of the Year award. He was a perpetual All-Star. And in 1955, he helped his team secure the championship. Robinson’s success was, by no means, inevitable and in fact he earned it in a society that sought to make it altogether impossible.

Unsurprisingly, his story seemed bound for Hollywood and in 1950, still in the midst of his career, he starred as himself in “The Jackie Robinson Story”. Now Robinson’s story returns to the screen in the new film “42,” this time played by Howard University graduate, Chadwick Boseman, who was at the American History Museum Monday evening for a special screening for members of the Congressional Black Caucus. We caught up with him there.

Are you happy to be back in D.C.?

I’m excited, you know, this room got me a little hyped. It’s fun coming here after having been here a few weeks ago after meeting the First Lady and the President for the screening at the White House. I went to college here and you always think, oh, I’m never going to get to go in that building, I’m never going to get to do this or that so coming here and doing it, it’s like wow, it’s a whole new world.

You said you can’t remember ever not knowing who Jackie Robinson was, but that it was important not to play him as just a hero. How did you get all those details? Did speaking with his wife, Rachel Robinson, play a big part?

The first thing that I did was, I went to meet her at her office on Varick Street. She sat me down on a couch, just like this, she just talked to me very frankly and told me the reasons why she was attracted to him, what she thought of him before she met him, what attracted her once they actually started conversing, how they dated, how shy he was, everything you could possibly imagine. She just went through who they were.

I think she sort of just started me on the research process as well because at the foundation, they have all the books that have been written about him. It was just a matter of hearing that firsthand information.

Then I met her again with children and grandchildren and in that case, they were sort of examining me physically, prodding and poking and measuring and asking me questions: Are you married, why aren’t you married? You know, anything that you could imagine. Actually, before they ever spoke to me, they were prodding and poking and measuring me and I was like, who are these people? And they said, you’re playing my granddad, we gotta check you out. It was as much them investigating me as it was me investigating him.

So they gave you a seal of approval?

They did not give me a seal of approval, but they didn’t not give it. They were willing to gamble, I guess.

Boseman met with Robinson’s family members in preparation for the role. Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment

He describes the relationship Robinson had with his wife (played by Nicole Beharie) as a safe haven. Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment

What were they looking for, what did they want to make sure you got right?

She was adamant about the fact that she didn’t want him to be portrayed as angry. That’s a stereotype that is often used, just untrue and one-dimensional with black characters and it was something that he had been accused of, of having a temper. In some senses, he did have a temper but it wasn’t in a negative sense.

I, on the other hand, after reading the script knew that it was necessary to not show him as being passive or a victim, which is another stereotype that’s often used in movies. I didn’t want him to be inactive, because if he’s passive, he’s inactive and you run the risk of doing another story that’s supposed to be about a black character, but there’s the white guy, there, who is the savior. There’s a point where you have to be active and you have to have this fire and passion. I view it more as competitive passion as Tom Brokaw and Ken Burns said to me today, that he had a competitive passion, competitive temper that any great athlete, whether it be Larry Bird or Babe Ruth or Michael Jordan or Kobe Bryant, they all have that passion. That’s what he brought to the table. . . .My grandmother probably would call it holy anger.

Was that dynamic something you were able to talk about with Harrison Ford, who plays the team executive Branch Rickey, and the writer?

First of all yes. But they already had really advanced and progressive points of view about it anyway and were very aware. Harrison was also very clear, even in our first conversations about it, that he was playing a character and I was playing the lead and that there are differences in the two.

There were instances where I might voice, this is what we need to do, and everybody listened to it and that’s definitely not always the case, definitely not always what you experience on the set. But I think everybody wanted to get it right. I can’t really think of a moment, I know that they came up where it was like, well I’m black so I understand this in a different way, but they do happen and everybody was very receptive to it.

Was there any story that Mrs. Robinson told you about him that stuck in the back of your head during the process?

She just talked about how he adapted after very difficult scenes where he was being abused verbally or threatened. She said he would go hit golf balls because he would never bring that into the house. The question that I asked that brought her to that was: Did he ever have moments where he secluded himself at home, or where he was depressed, or you saw it weighing on him? And she said: ‘No, when he came into our space, he did whatever he needed to do to get rid of it, so that our space could be a safe haven, and he could refuel, and could get back out into the world and be the man he had to be.’

And she’s going through it just as much as he is. She’s literally in the crowd. People are yelling right over, calling him names right over her or calling her names because they know who she is. That’s something people don’t really think about, that she was actually in the crowd. She has to hold that so she doesn’t bring that home to him and give him more to worry about and that’s a phenomenal thing to hold and to be strong. I love finding what those unspoken things were that are underneath what’s actually being said.

What do you hope people will take away from the film?

I hope they get a sense of who he really is. I think what’s interesting about it is that he played himself in that original 1949-1950 version. . .What I found is that him having to use the Hollywood script of that time does not allow him to tell his own story because he couldn’t really be Jackie Robinson in that version.

It wasn’t his exact story, if you look at the version it says all he ever wanted to do was play baseball and he didn’t. Baseball was his worst sport, he was a better football player, better basketball player, better at track and field. He had a tennis championship, he played golf, horse back riding, baseball was the worst thing he did. I’m not saying that he wasn’t good at it, I’m saying that it’s not the truth. He was a second lieutenant in the army, he was All-American, he led his conference in scoring in basketball and he could have been playing in the NFL, but he had to go to Hawaii and play instead.

So what is that? Why did he end up playing baseball? Because baseball was where he could actualize his greatness, it wasn’t the only thing that he was great at and so just that little untruth in the script skips all of the struggle that he had getting to the point of being in the minor leagues. He’s doing this because it’s one more thing that he’s trying to do in that United States at that time that maybe will allow him to be the man that he wants to be. He could have done any of those other things, it just wasn’t an avenue for him to actualize his full humanity, his full manhood and so that version doesn’t allow him to be Jackie Robinson.

When I look at this version, we live in a different time where you can tell the story more honestly. Ultimately I think that’s what you should take away from the film, I get to see who he is now because we’re more ready to see it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)