A Rare Insider’s View of Native American Life in Mid-20th-Century Oklahoma

Horace Poolaw’s photography is unearthed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian

Horace Poolaw never aspired to have his photographs in museums, or to even be printed large enough to frame.

A member of the Kiowa tribe, Poolaw had just one show in his lifetime, at the Southern Plains Indian Museum in his hometown of Anadarko, Oklahoma.

He printed a few as post cards to sell to tourists—sometimes with the inscription on the back “A Poolaw Photo, Pictures by an Indian,”—but it was never clear whether his intention was merely to depict his people or promote their tradition.

Indeed, most of the images taken over five decades and now on view in the exhibition “For a Love of His people: The Photography of Horace Poolaw,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., had never been printed at all until after his death in 1984. The show is co-curated by Native scholars Nancy Marie Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache) and Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk). Mithlo also served as general editor of the exhibition catalogue and Jones contributed an essay.

Critical recognition came only after his daughter Linda Poolaw started to organize an exhibition at Stanford University in 1989. Experts began taking a closer look at the negatives he had left behind. Only then did Poolaw, who had documented the life of native peoples in rural Oklahoma, emerge as a primary and significant Native American photojournalist of the 20th century.

According to Alexandra Harris, an editor on the project, his work was found to be more noteworthy because it was a time when “Native Americans became invisible in the national visual culture. We believe that Poolaw’s photography really fills part of that gap.”

Although photography was only a hobby for Poolaw, he used a secondhand Speed Graphic camera —the kind that newspapermen used throughout most of the 20th century— to journalistically capture scenes of everyday life on the reservation. His images include ordinary birthday parties and family gatherings, but also stunning portraits of returning military veterans, tribal celebrations and especially the annual American Indian Exposition that still continues in Anadarko.

It was important, Harris says, that Poolaw worked not as an outsider looking in, but as part of the community.

“There were very few Native photographers in the early to mid-20th century, witnessing their communities, and the diversity of what he saw, as an insider,” she says.

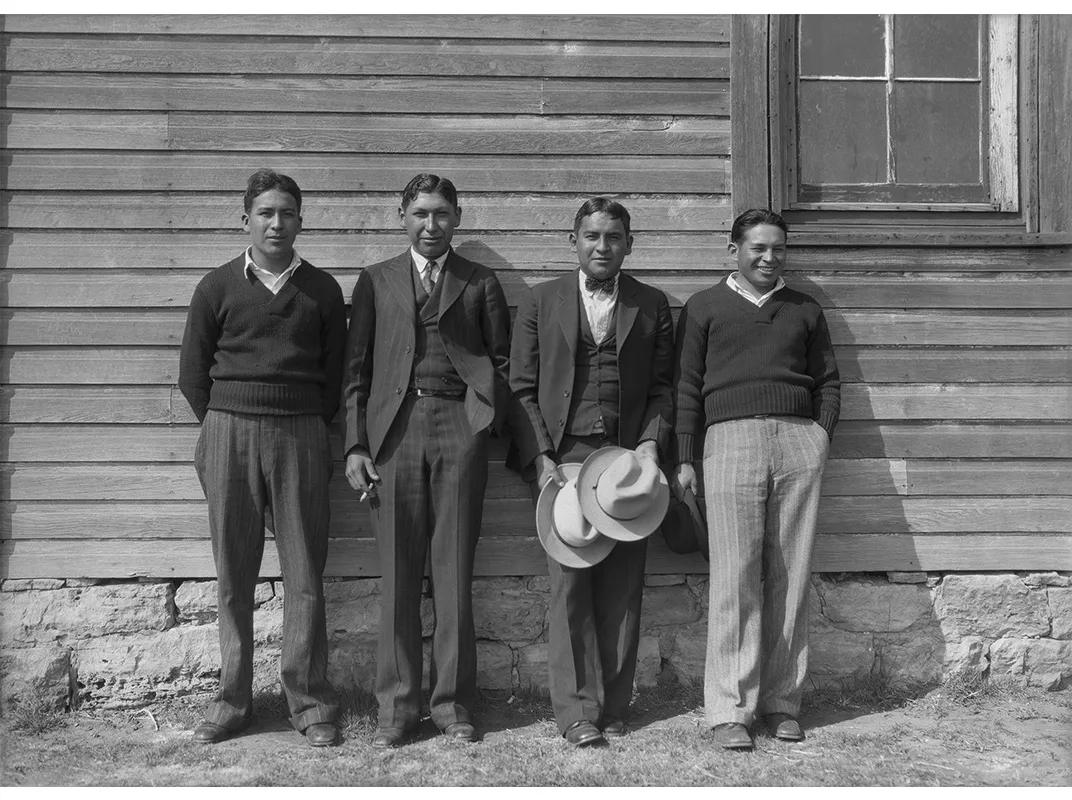

As such, he captured a time when Native culture was in transition, and people were assimilating on their own terms—not in the forced way that had come earlier. At the same time, tribes were changing, bringing back and embracing elements of their native customs and language that had been banned on the reservation.

The Horace Poolaw exhibition, which first debuted in 2014 to 2015 at the Gustav Heye Center, the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, reflects that combination of cultural influences, as in a scene of a parade heralding the start of the 1941 American Indian Expo that features a trio of women in Kiowa regalia riding not horses, but a shiny Chevrolet.

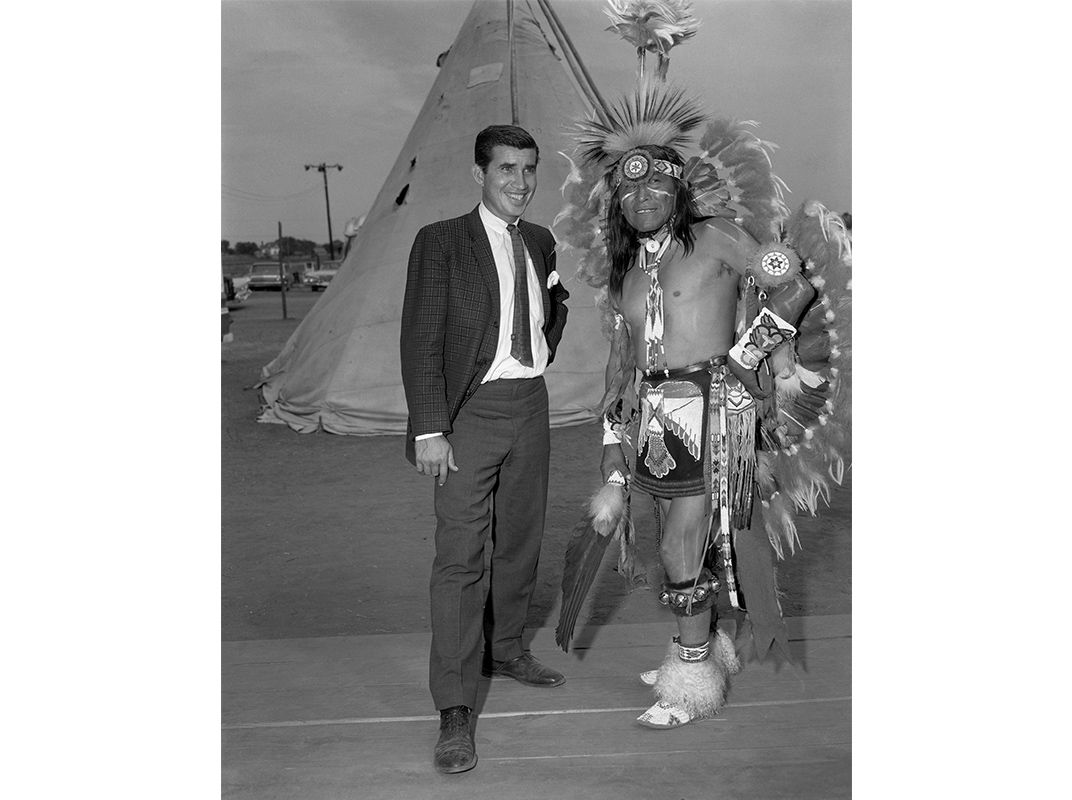

It’s a more stark contrast in a portrait of smiling Oklahoma broadcaster Danny Williams, standing next to champion Indian dancer and painter George “Woogie” Watchetaker in full Comanche regalia and headdress. A tipi stands behind them, but also a parking lot with late model cars.

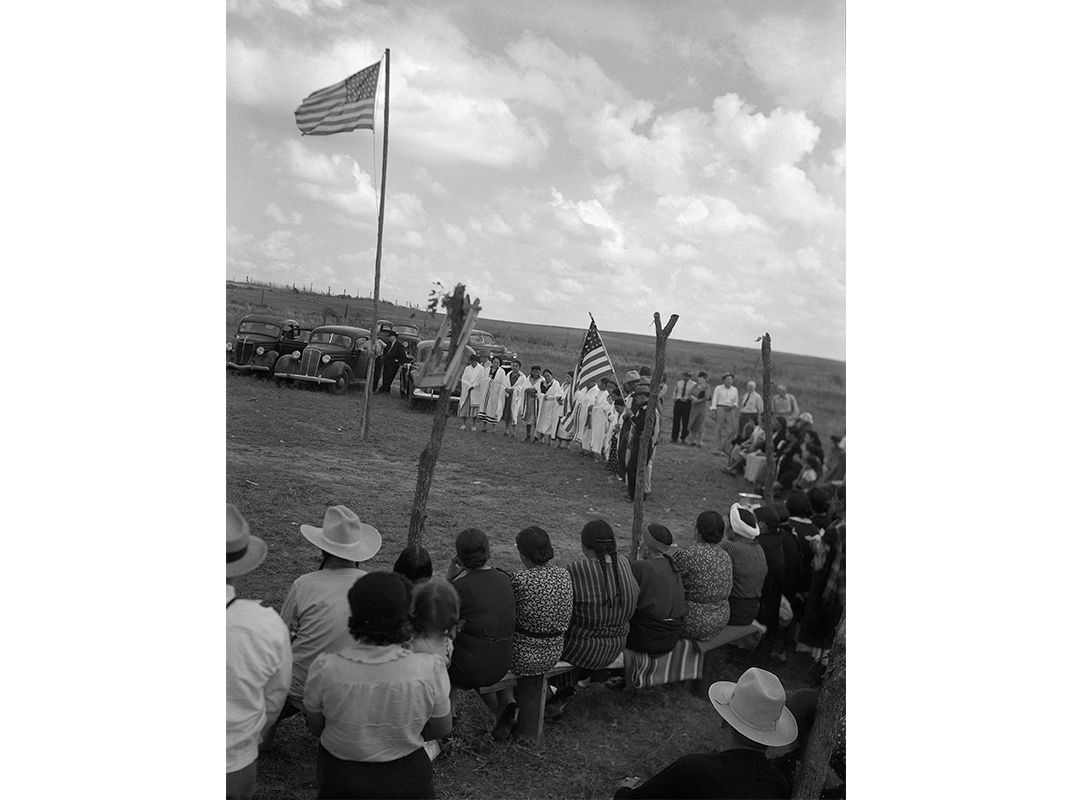

Ceremonies not tied to the expo are also chronicled, from the circle at a 1945 powwow in rural Carnegie, Oklahoma, with some in Western wear and cowboy hats and others in traditional shawls, an American flag flying in the cloudy sky and a few sedans comprising the rest of the arc.

Even less formal, and more immediate in its reality, is the funeral of Agnes Big Bow, a Kiowa tribe member in Hog Creek, Oklahoma, in 1947, where the pallbearers, many in western gear and hats are placing the Western-style casket into stony cemetery ground.

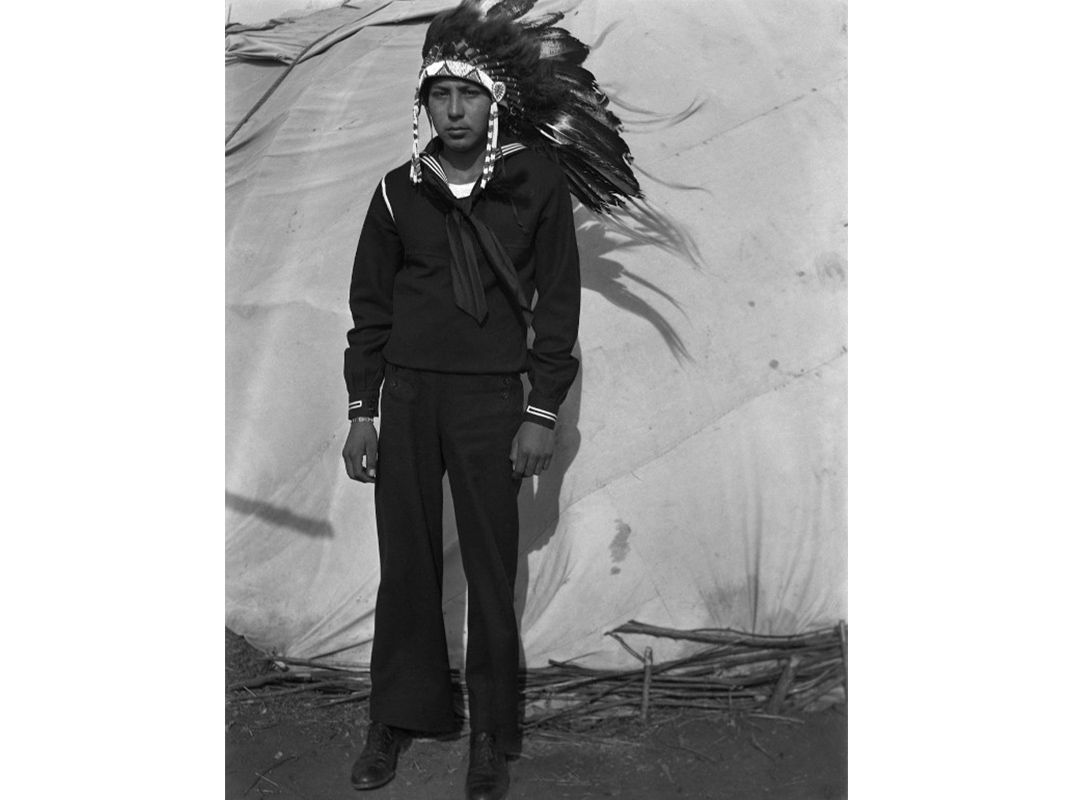

The intersection of the tribe and the U.S. military was an important one for Poolaw and it is the image of his son Jerry, on leave from duty in the Navy in 1944, in uniform but with his full feather headdress that is the main image of the exhibition.

That same year, Poolaw himself poses alongside another Kiowa, Gus Palmer, in front of a B-17 Flying Fortress at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa where he was trained at an aerial photographer—their traditional headdresses contrasting with their uniforms.

Still, the war bonnet, as it was sometimes known, was not just a fancy accoutrement, but one earned by valor by tradition, and serving in the military certainly counted.

“Three hundred Kiowa men were in active duty in World War II and when they came back after having experiences in battle with which they could earn valor, they could earn the honors that the old military societies would give them,” Harris says. “So they reenstated some of these societies, and it brought back a lot of the material regalia culture that came with it.”

Children are a poignant subject matter in his photographs—whether they dress up in 20th-century tweed coats and ties, cowboy attire or native regalia.

The blending of Native culture into the wider realm of entertainment could be seen in the career of Poolaw’s brother Bruce who went on the vaudeville circuit as Chief Bruce Poolaw and married fellow performer Lucy Nicolar, a Penobscot woman and mezzo-soprano who was known as “Princess Watahwaso.” Naturally, they’d pose theatrically for Poolaw, as well.

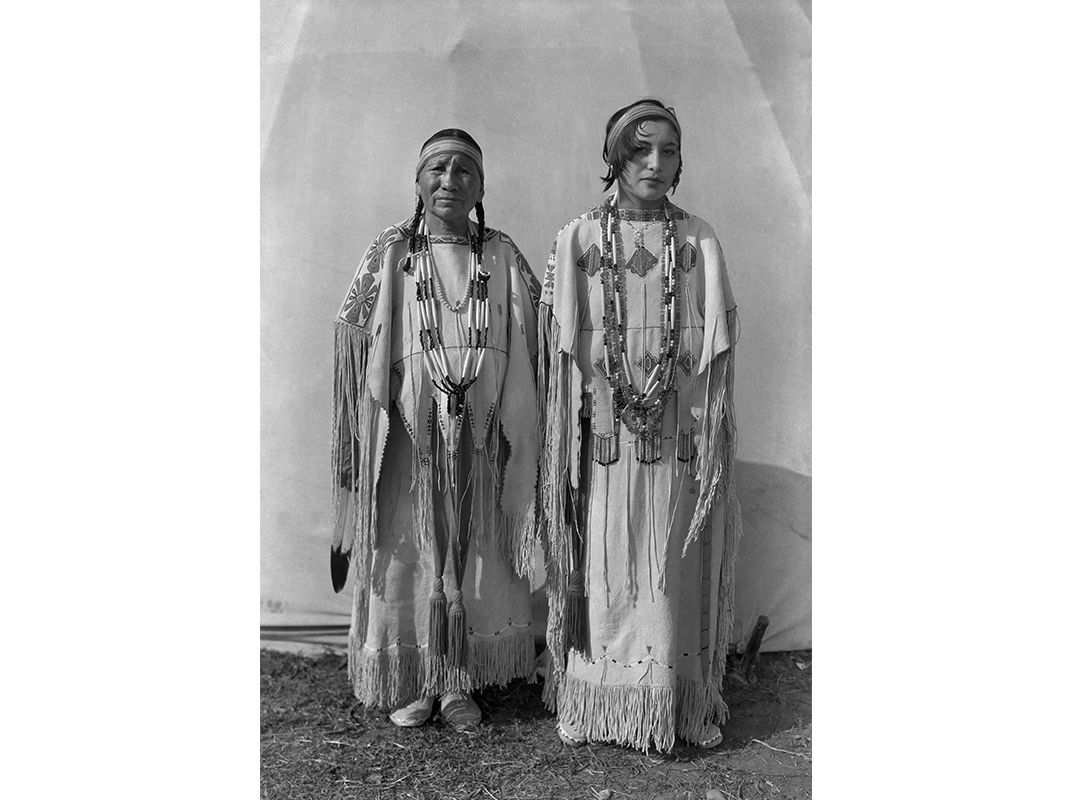

Another striking example of modern Western tastes colliding with traditional Native culture is in the photos of Hannah Keahbone, who wore makeup and had her hair in a bob that was fashionable in the 1920s and 30s, alongside her mother sandy Libby Keahbone, in more traditional braids and no makeup.

Laura E. Smith, an assistant professor of art history and visual culture at Michigan State University who specializes in Native American art and photography, writes in the catalog accompanying the exhibition that though both are wearing traditional Kiowa regalia in the double portrait, it shows how women of the tribe “negotiated the terms for female identity among themselves.”

Capturing moments like this, Poolaw was inspired more by Life magazine photojournalism than the kind of Native portraits intended for museums. Poolaw didn’t intend to make deep sociological points about the people he portrayed—although his photographs often end up doing so.

“He never really wrote down why he did things. So we really have to guess,” Harris says. “In conversations with his daughter, she talks a lot about his love of these people. And it could be as simple as him acting as a witness for his time. ”

“For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw” continues through June 7, 2017 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall, Washington D.C. The show is co-curated by Native scholars Nancy Marie Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache) and Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk). Chair of American Indian studies at the Autry National Center Institute and associate professor of art history and visual arts at Occidental College, Mithlo also served as general editor of the exhibition catalogue. Jones, an associate professor of photography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, also wrote an essay for the catalogue.

UPDATE 11/30/16: An earlier version of this story misattributed quotes to another of the exhibition's curators. The quotes are from Alexandra Harris. We regret the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/7f/9d7fda6d-4706-4897-94bb-6e5a3916fdb6/57fk1cl-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)