A Renowned, But Forgotten, 17th-Century Japanese Artist Is Once Again Making Waves

Long neglected, the 17th-century Japanese artist Tawaraya Sōtatsu influenced Western art 400 years later

It was 109 years ago, on a fall day in 1906, when Detroit art collector Charles Lang Freer agreed with a visiting dealer on a price for a Japanese screen by a little known artist named Tawaraya Sōtatsu.

The purchase of a work that became known as Waves at Matsushima, he wrote to a fellow collector, only came “after much dickering of a most exasperating nature” with the Tokyo dealer. He paid $5,000 for a pair of six-fold screens—the other by Hokusai—a price that was half of what the dealer was originally asking. But he ended up with a priceless and influential work that is currently centerpiece to what’s being billed as a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition in Washington, D.C.

“Sōtatsu: Making Waves” is the first major retrospective in the Western hemisphere devoted to the 17th- century artist—the first and only opportunity to see more than 70 pieces of his work from 29 lenders from the U.S., Japan and Europe on display together, amid works later artists did in homage to one of the most highly influential artists of his time.

The exhibition is only showing at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, because of stipulations made when Freer pledged his collection to the country—a pledge that coincidentally also came in 1906—that the work not travel.

“In pledging his collection, Freer sought to encourage greater understanding and appreciation of Asia and its artistic traditions among his fellow Americans,” writes Julian Raby, the director of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, in his forward to the accompanying catalog to “Making Waves,” itself the first English-language survey of Sōtatsu’s art and a richly designed and elegant volume.

In making that long-ago purchase, Raby says, “[Freer] instinctively sensed that Sōtatsu, little known in Freer’s day, would emerge as a figure of singular importance in the history of Japanese art.”

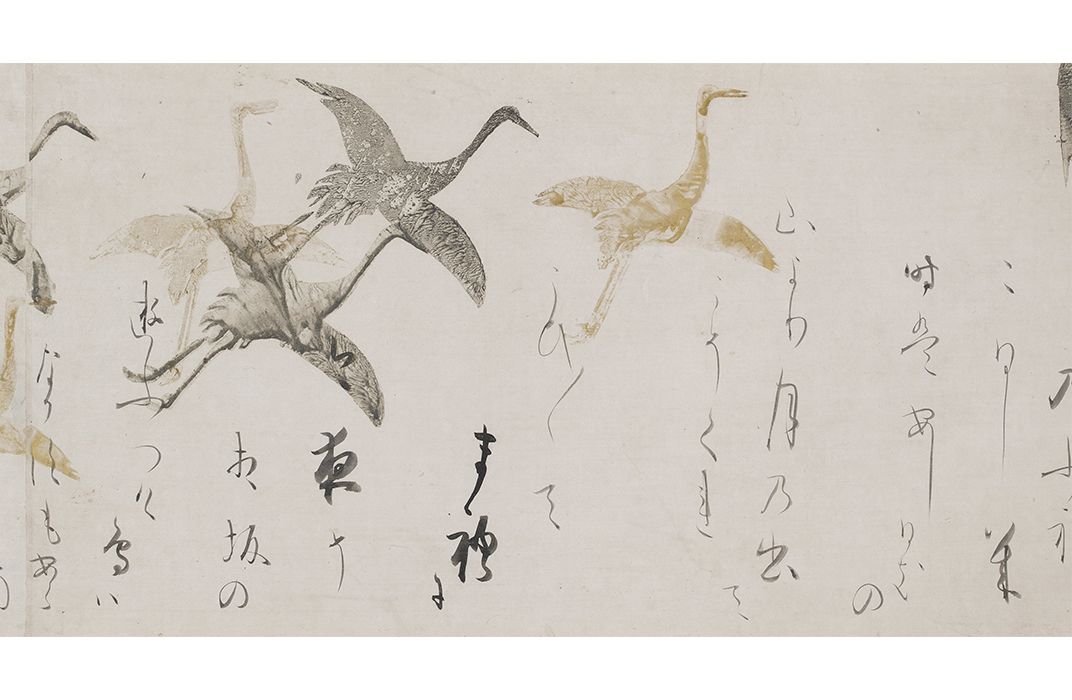

The D.C. exhibition coincides with the 400th anniversary of the Rinpa style of painting, which began as a process of dropping ink onto a wet background to create delicate detail, also known as tarashikomi. A related exhibition at the Freer and closing next month when that esteemed gallery undergoes a two-year renovation is entitled “Bold and Beautiful: Rinpa Screens” and traces Sōtatsu’s influence on the work of other artists as well, including Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and his brother Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743).

Less is known about the biography of Sōtatsu. He is thought to have been born in 1570 and lived until about 1640—but his designs revolutionized Japanese art and survived to influence works 400 years later, from the likes of Gustav Klimt to Henri Matisse.

The six-fold screen at the center of the exhibit, Waves at Matsushima with its shimmering gold and silver tones, is believed to have been created about 1620. The work didn’t acquire its name until about 100 years ago. The title refers to an area of small pine-covered islands in Japan that came to be well known in recent years for having survived the 2011 tsunami.

“Freer didn’t buy them as ‘The Waves of ..’ anything,” says James Ulak, senior curator of Japanese art at the Freer and Sackler and who co-curated the exhibit. “They were simply described as ‘Roiling Waves and Rocks,’” Ulak says of the screens, “which is probably just as well. It doesn’t indicate a specific place.” The swirls and eddies of the water doesn’t necessarily indicate treacherous crossings, Ulak says. “Roiling waters, in hand scrolls and religious tracts, are things from which blessings emerge,” he says. “Just because it’s stormy, doesn’t mean it’s bad.”

And amid the swirling waters are rocks of safe shores, sandbars and pines.

“Sōtatsu literally made waves in his brilliant reworking of visual traditions for a vital new society that was emerging in early 17th-century Kyoto,” says Raby, who calls them “screens of utmost importance in the history of Japanese art. “In scale, elegance, illusion and looming abstraction, they announced a stylistic turn that would influence Japanese art and indeed Western art well into this century,” he says.

“And it is these screens, these waves, that form the pivotal point for this exhibition.”

With its precise and hypnotic lines of water amid branches and the much more abstract smudges of rocks, Ulak says, “the screen itself is an absolute encyclopedia of Sōtatsu’s technique, his use of pigments, his blending of pigments without lines, letting degrees of tonality form images.”

And where there are lines in the crashing waves, Ulak says, “look at these waves and think about holding a brush and doing this. Look at the line. It’s an incredible work of craft.”

And the showpiece is only the beginning of the exhibition, which covers the artist’s days as a craftsman and commoner in a Kyoto fan shop, his collaborations with a great calligrapher of the time, Hon’ami Kōetsu, and his work as a restorer of ancient texts such as the Lotus Sutra. The artist’s relatively speedy ascent from craftsman to favored artist of the sophisticated elite was something new at the time.

“Sōtatsu appears at a time when a whole society is shifting,” Ulak says. By incorporating older images from hand scrolls of 12th- to 14th-centuries on a series of fans, “you see the phenomenon of everyone with some means in Japanese society being able to become fluent with the mantle of a unified past.”

His success with the nobility led to creating a studio where as part of a team he created some stunning artwork and later, influenced artists for centuries to come. But over the centuries, Sōtatsu’s name faded from memory.

Likely originally commissioned for a temple by a wealthy sea captain, “Waves at Matsushima” only became wider known after a pair of exhibitions in the early 20th century.

One show was in 1913 and revived Sōtatsu’s reputation among artists in Japan but also in Europe, where his jewel tones and flat landscapes had direct influence on artists from Henri Matisse to Gustav Klimt. The other came in 1947, Raby adds when, “in the rubble of a just-concluded war, the Tokyo Museum held two remarkable parallel exhibitions, one was on Sōtatsu and the other on Matisse.

“To young Japanese artists who viewed the exhibitions, the coincidence was undeniable,” Raby says. “No one could miss the parallels. For Sōtatsu’s vocabulary seemed so very modern.” It only took, he said, “in the space of less than a generation, an entire shift, the forefront of which was Charles Lang Freer,” he says.

“And in recognition of this, in 1930 a monument was erected to Freer in Japan. Where? Not just in Kyoto,” Raby says, “but adjacent to Sōtatsu’s grave.”

“Sōtatsu: Making Waves” continues through Jan. 31, 2016 at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)