Reports on the Death of the Circus Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

Celebrating the arts, business, history and culture of the circus, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival brings 400 performers to the National Mall this summer

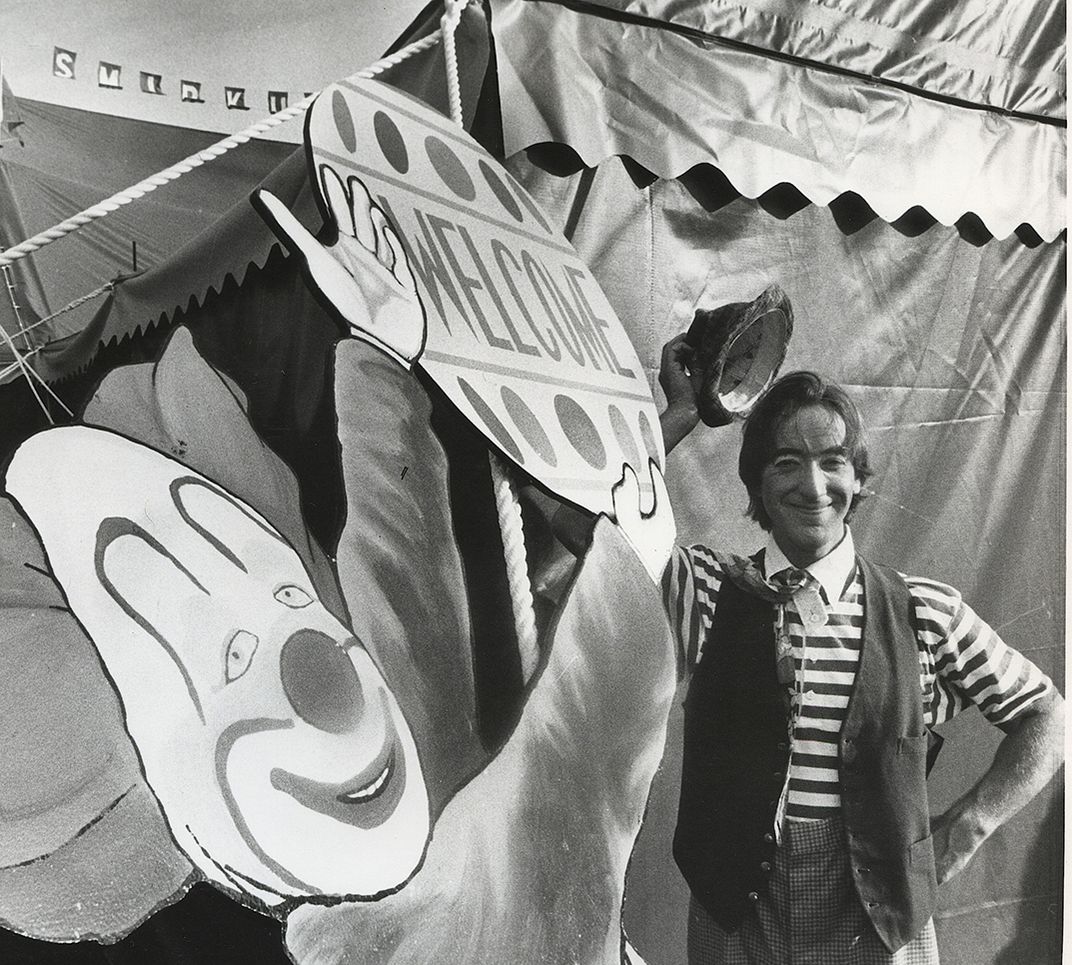

As a kid, Rob Mermin didn’t dream of running away to join the circus. But as a college student in the late 1960s, amidst war protests and civil-rights struggles, he sought an alternative path that might help make the world a better place through humor—without malice, without cynicism and without violence.

“I knew there were still tent shows in Europe, and I was curious about circus life, so I thought I could go over there and apprentice myself to a clown and learn the trade,” Mermin recalled.

“I was 19 years old and found myself hitchhiking around England looking for a circus, with $50 in my pocket, which I figured would last me three days. And sure enough on the third day, late at night on the border with Wales, I found a circus tent in a field popped up like a mushroom. I crept under the big top, slept under the bleachers with straw and sawdust for a pillow, and the next morning I asked for a job. When I mentioned the word clown, the boss interrupted me, grinning slyly, and declared, ‘You’re a clown! Fine—the matinee is at 11, put your make-up on over there.’ And that was it. The next thing I know, I’m thrown into the ring: riding a bucking camel, chased by an ornery mule, and running around with two new partners: a Spanish tightrope walker and a Latvian clown who doubled as animal trainer. This was the life! Bruised, battered, and exhausted, I slept with the elephants that night, knowing that if I survived, I’d have stories to tell when I’m old.”

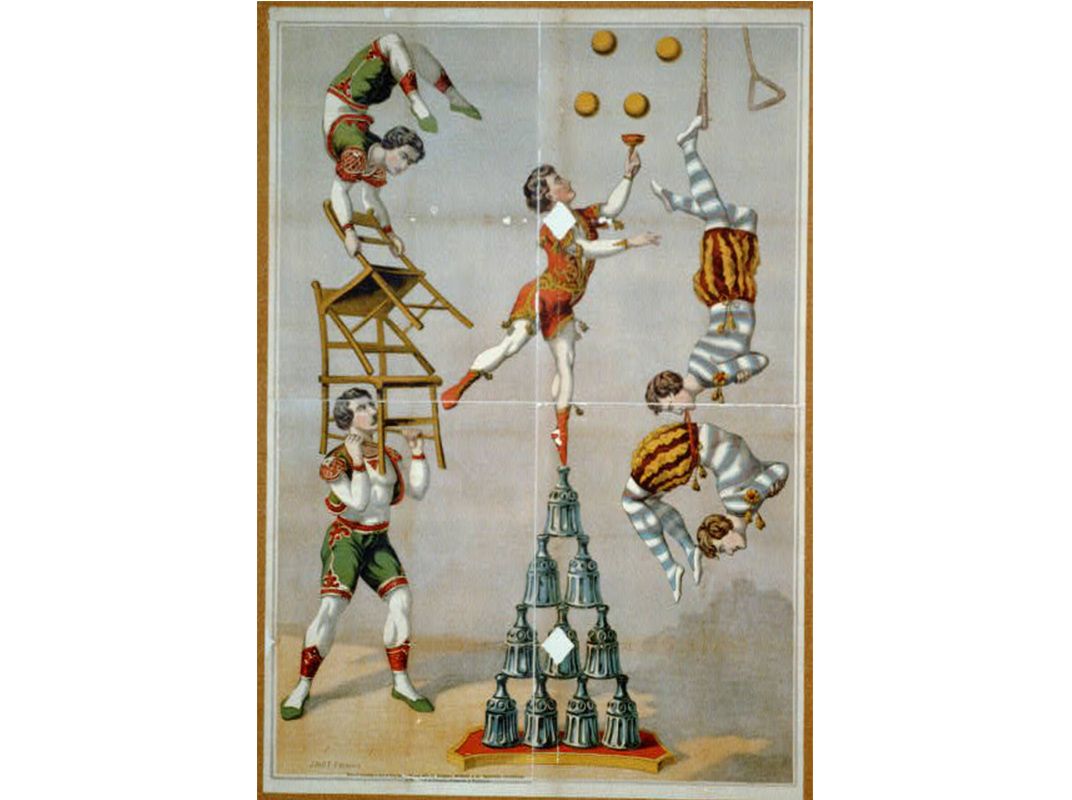

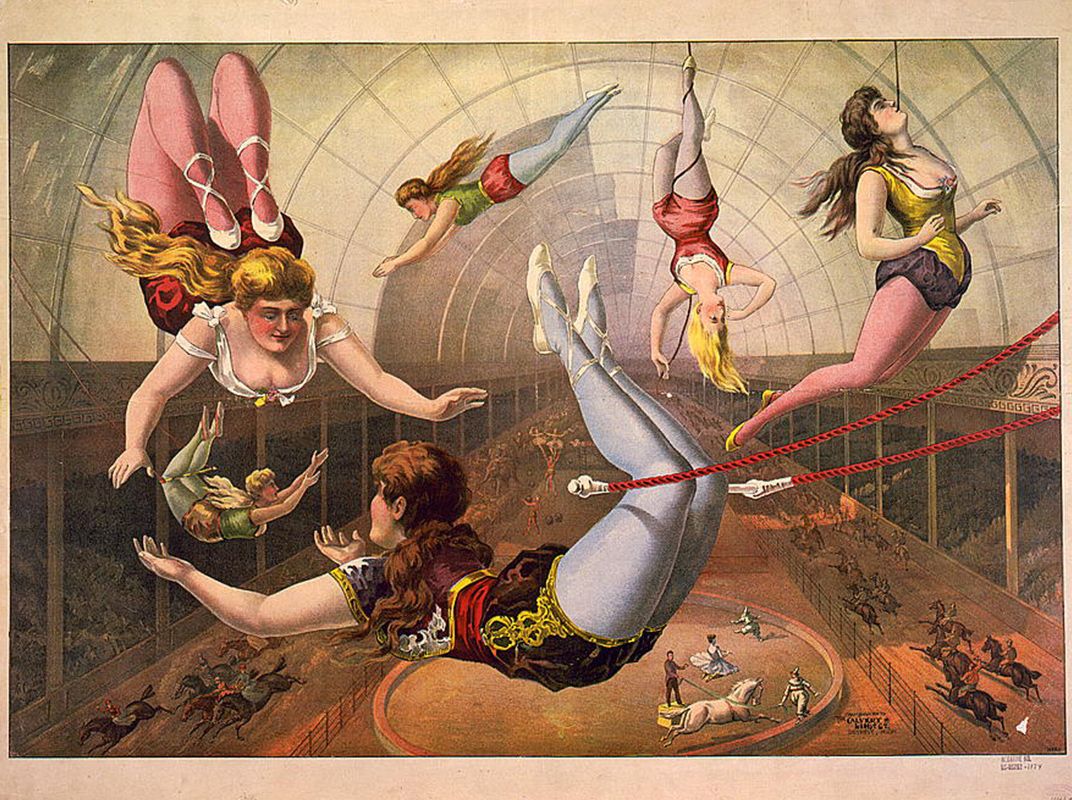

The eighth annual World Circus Day is celebrated on April 15, exactly 75 days before the Smithsonian Folklife Festival opens on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. On June 29, the Festival’s tents this year will play host to an ambitious program devoted to Circus Arts with some 400 participants—acrobats, aerialists, clowns, cooks, equilibrists (or tightrope walkers), musicians, object manipulators (or jugglers) and riggers—invited to demonstrate and share their skills and traditions. Well-known circus performers will appear alongside students from circus schools arriving from communities in California, Florida, Minnesota, Missouri, Vermont, Washington and elsewhere.

Mermin will be one of the participants. After his circus debut in 1969, he spent much of the next 20 years working as a clown and mime in Europe, where he not only honed a variety of skills, but also came to appreciate the model of the traveling, family-owned circuses. He sought to replicate those traditions with the founding in 1987 of the award-winning Circus Smirkus in Greensboro, Vermont that teaches the circus arts to children and teens.

“I wanted to recreate for American children what I had experienced in European circuses: working under canvas, an intimate show with live music, and communal living in caravans, where the circus families are very tightly knit, living and working together.” This European tradition, which continues today, stands in contrast to the enormous circus enterprises that were the norm in the United States from the late 19th to the mid-20th century.

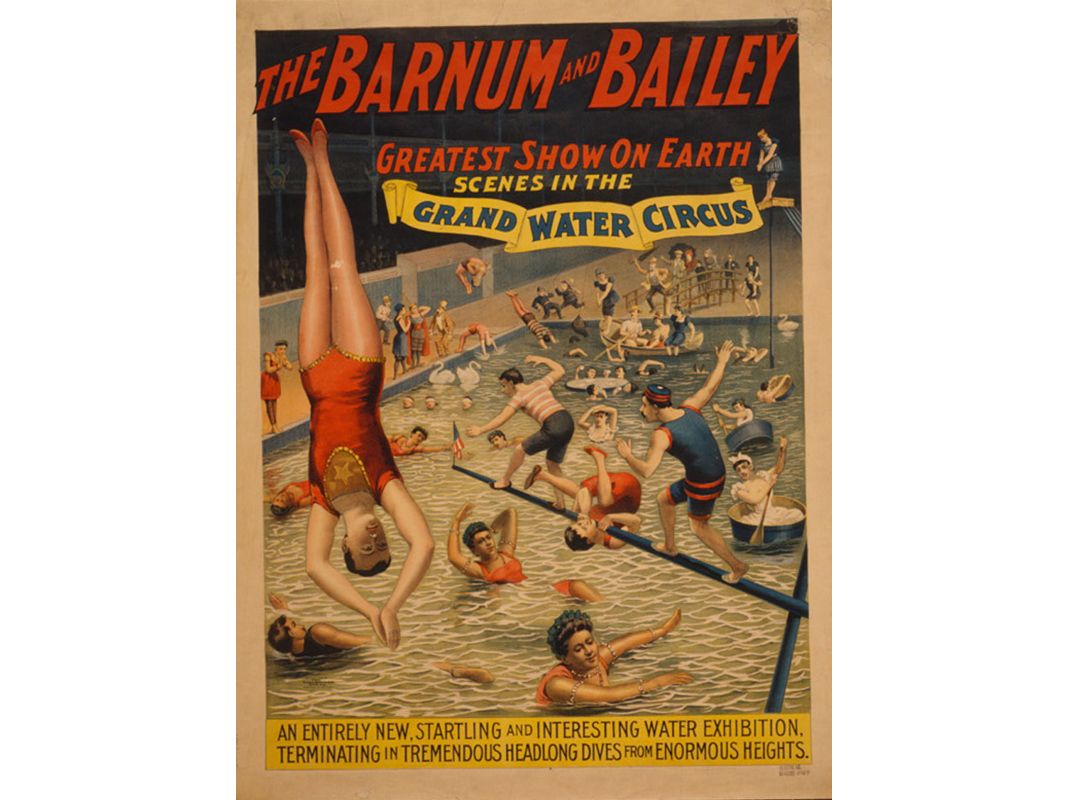

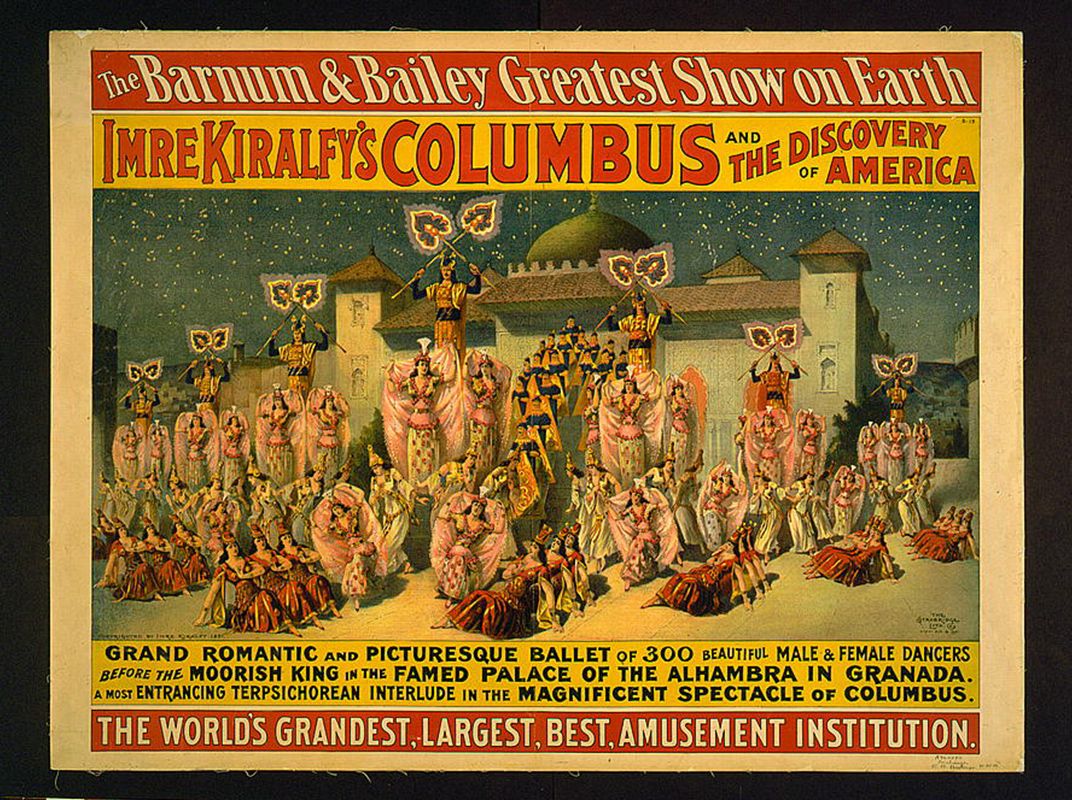

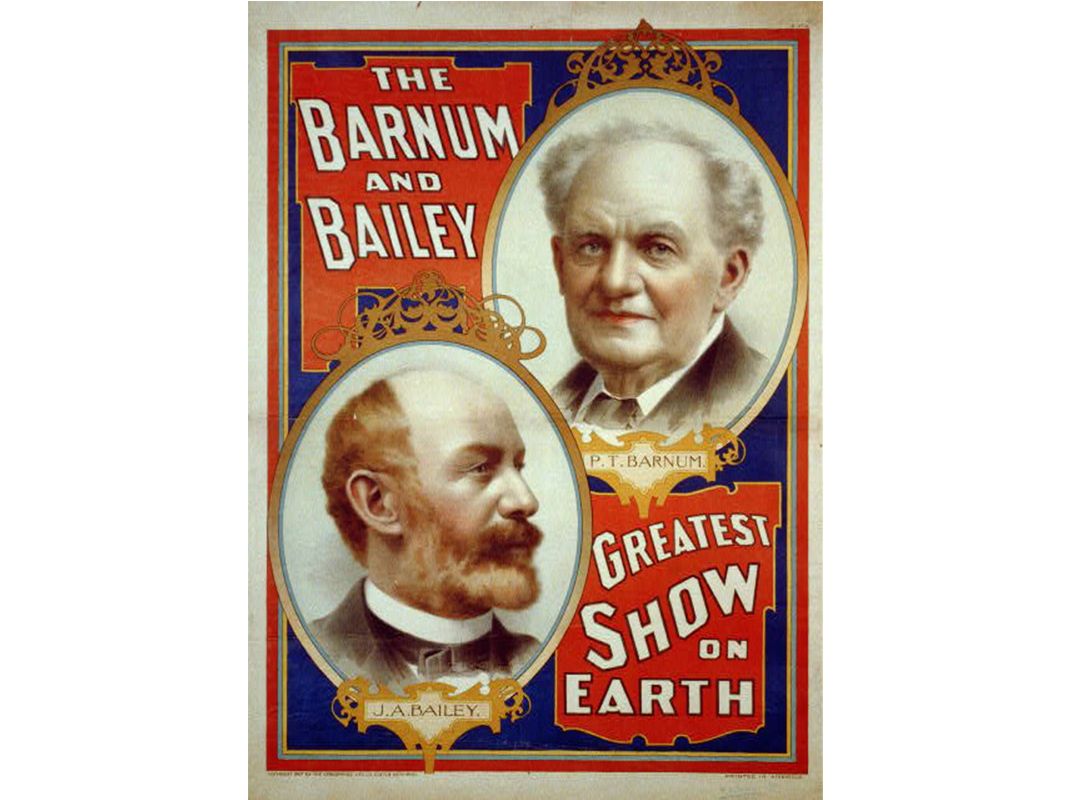

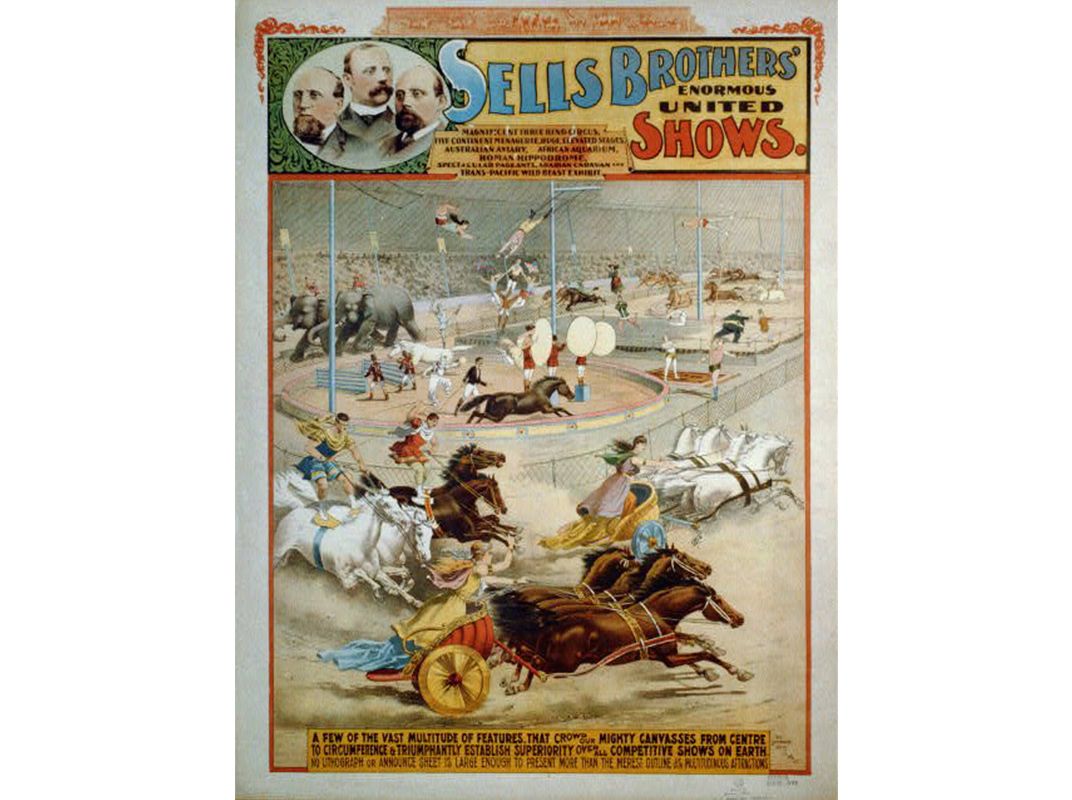

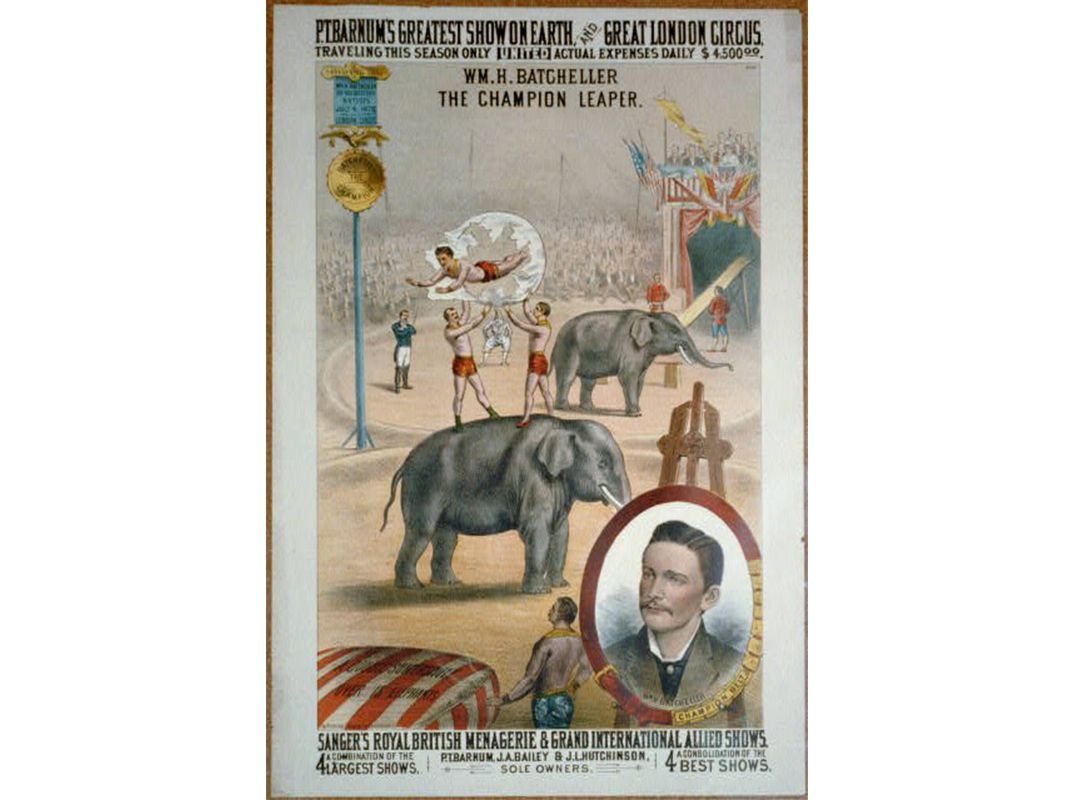

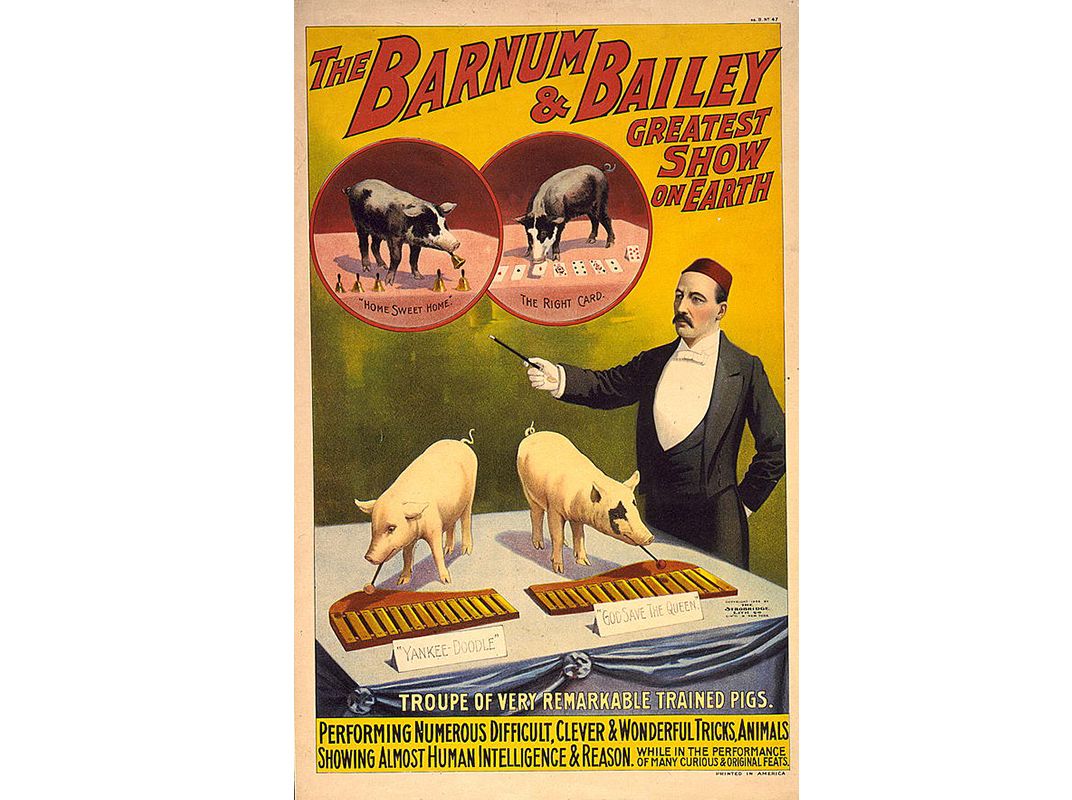

The largest of those enterprises, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, announced in January 2017 that it will close in May after 146 years of performances. Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey epitomized the American style of circus. It was big (three rings, hundreds of animals, and more than a thousand performers and support staff), bold (introducing new acts, often imported from Europe), and brassy (billing itself as no less than “the greatest show on earth,” with typical American hyperbole).

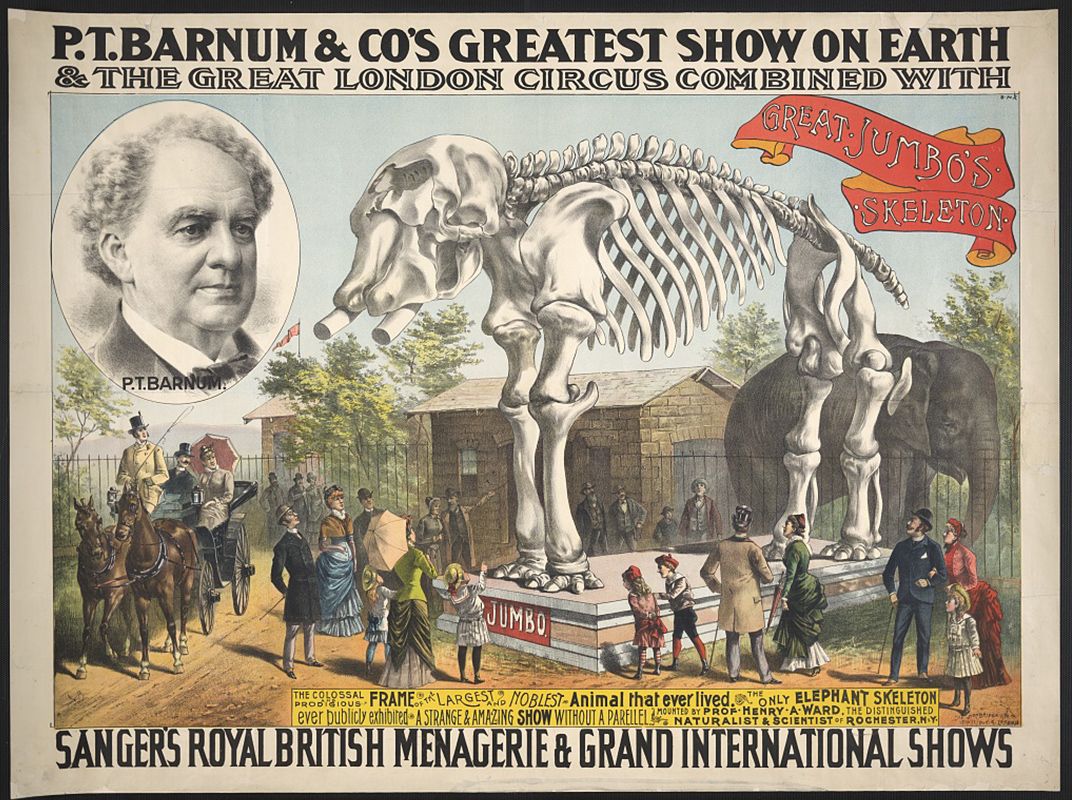

The master of such talk was the circus showman P.T. Barnum (1810–1891), who not only coined the phrase “greatest show on earth,” but who also is typically credited (even if incorrectly) with aphorisms such as “Every crowd has a silver lining” and “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/4f/5f4fa7e1-6173-4d57-b610-7b1a80e59037/npg93154detbarnumrweb.jpg)

Barnum also heavily promoted what he termed “living curiosities.” These included Charles Stratton (a.k.a. General Tom Thumb); Chang and Eng Bunker, conjoined twins from Siam (now Thailand), which is why such twins became known as Siamese; Josephine Clofullia (a.k.a. the Bearded Lady); and Isaac W. Sprague (a.k.a. the Living Skeleton). Often exhibited in a sideshow outside the main tents, these and other “curiosities” lent a sensationalist and to some an unsavory reputation to the circus, which lingered in certain quarters throughout the end of the 20th century.

Because of this reputation, scholars and cultural critics paid less attention to the circus arts than they did to other forms of popular culture, particularly music and film. It is only in the past two to three decades that a more analytical and sophisticated scholarship began to emerge, books like the 2002 The Circus Age: Culture and Society Under the American Big Top by Janet M. Davis, a professor of history and American Studies, who also recently authored an article about circus misconceptions in the Washington Post; and Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittmann’s 2012 The American Circus; as well as Linda Simon’s well-researched 2014 The Greatest Shows on Earth: A History of the Circus. Davis, Wittmann, and Simon are also serving as advisors to the Smithsonian Folklife Festival program on circus arts.

This recent scholarship demonstrates that the history of circus in America consistently parallels and reflects the history and evolution of the United States itself in several significant ways. Circus culture—like much of America’s artistic and cultural heritage—initially originated elsewhere. But it developed and thrived in the United States, just as the immigrants established themselves in their new homes, building upon the contributions of their predecessors and passing their traditions and skills to the next generation. Circus performers brought international diversity and multiculturalism to many parts of the country that were otherwise homogeneous.

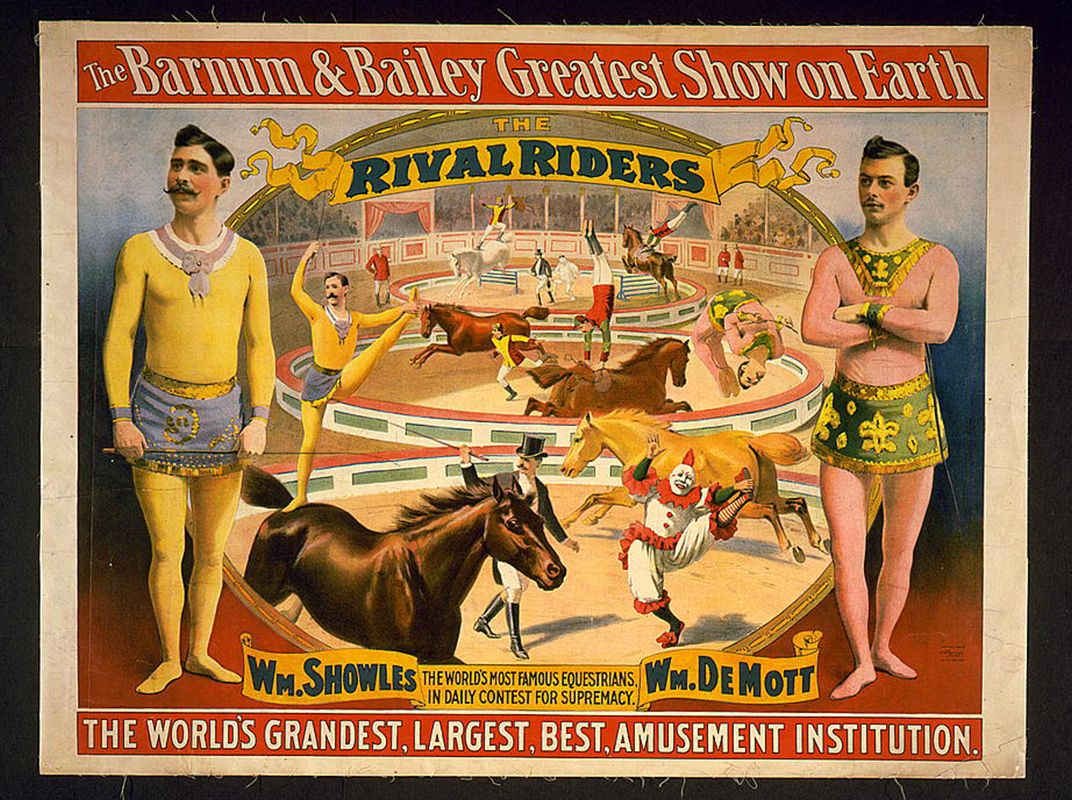

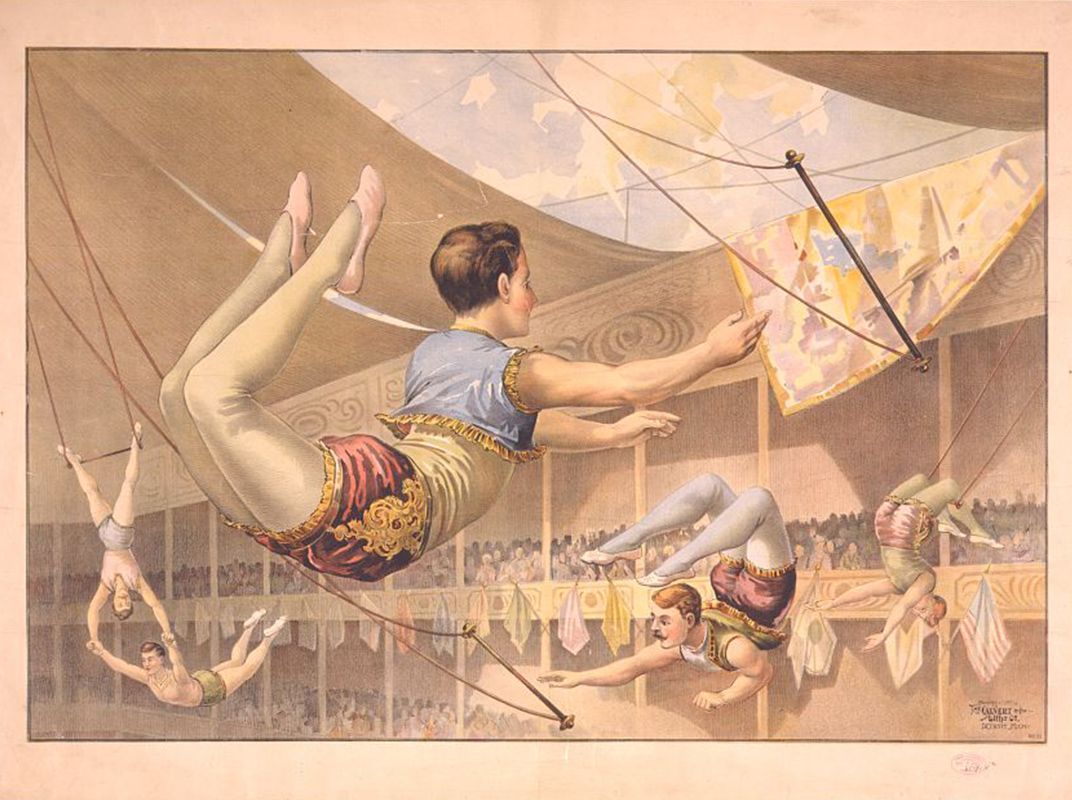

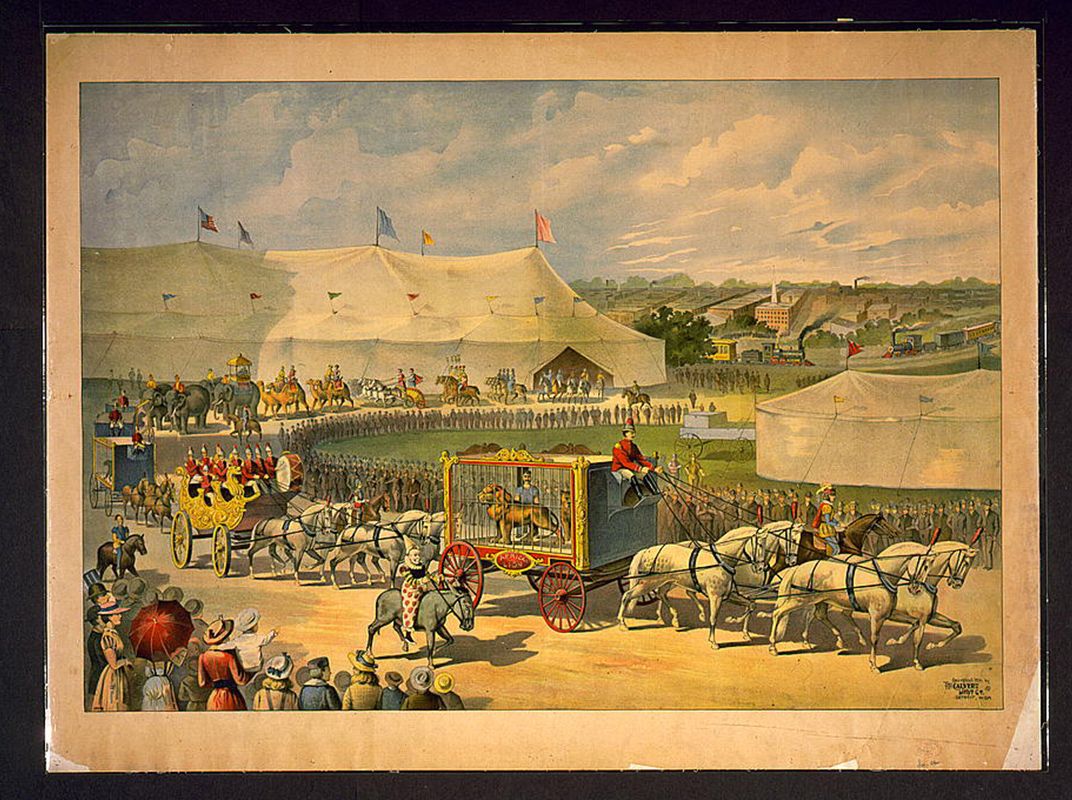

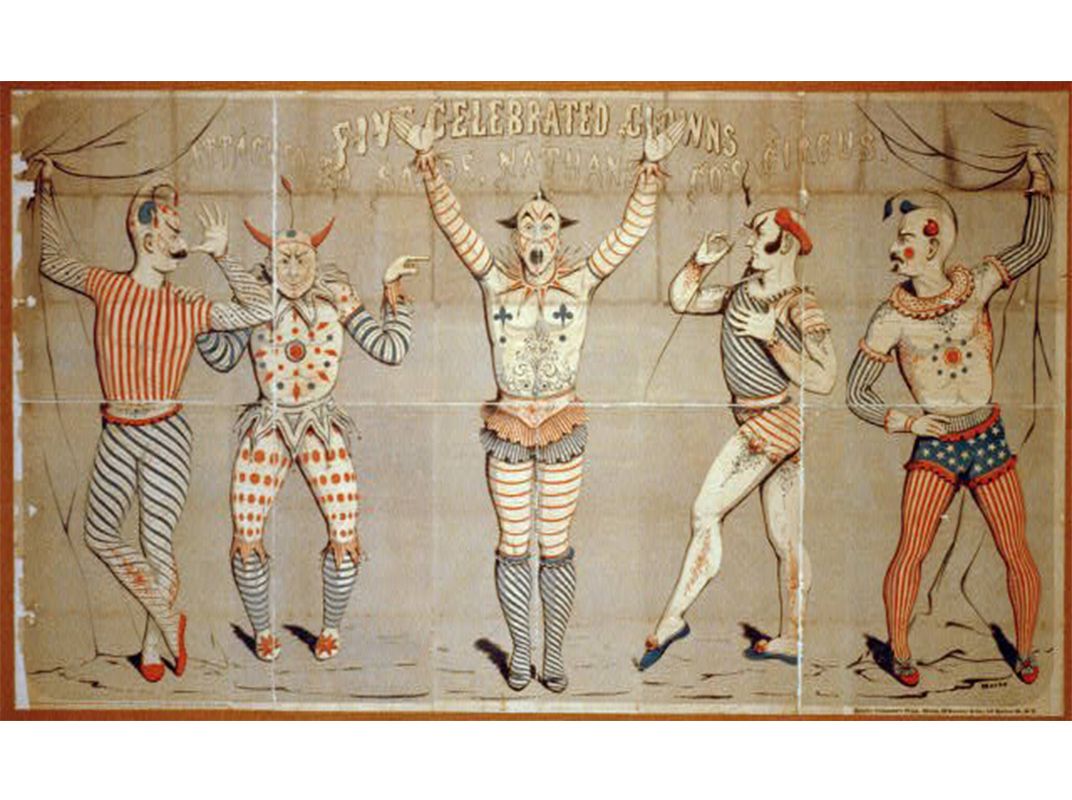

Circus history also parallels the histories of science and technology, conglomeration and industrialization, and advertising and marketing in the United States. Circuses could not have prospered without electrification to illuminate the big tops or the transcontinental railroad to transport the circus troupes. The consolidations and mergers that created the Standard Oil Company, U.S. Steel Corporation and American Sugar Refining Company, drove the mergers that created the large circuses. And brightly colored circus posters (above) crafted from the latest lithographic techniques decorated the sides of every available surface in town and country. P.T. Barnum and other entrepreneurs used every possible means—including advance teams and spectacular parades—to attract audiences of all ages.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)