“Roads of Arabia” Presents Hundreds of Recent Finds That Recast the Region’s History

More than 300 objects begin a North American tour at the Sackler, adding new chapters to Saudi Arabia’s history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121115030029Incense_Thumb.jpg)

Art exhibits rarely come with their own diplomatic entourage, but the new groundbreaking show at the Sackler, “Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” does. The show’s 314 objects that traveled from the Saudi peninsula were joined by both Prince Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, president of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, and the Commission’s vice president of antiquities and museums and the show’s curator Ali al-Ghabban.

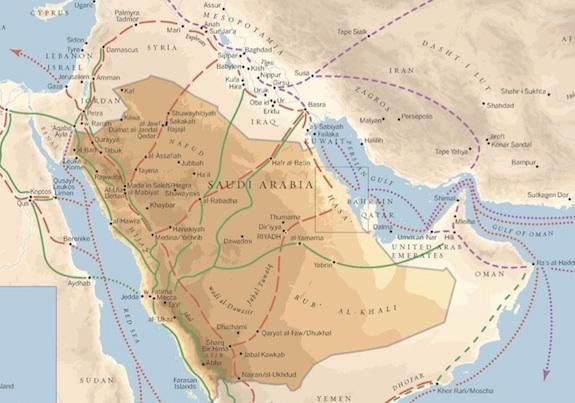

“Today we hear that Arabia is a desert and petrol wealth. This is not true,” al-Ghabban says. Instead, he argues, it is a land with a deep and textured past, fundamentally intertwined with the cultures around it from the Greco-Romans to the Mesopotamians to the Persians. Dividing the region’s history into three epochs, the show moves from the area’s ancient trade routes at the heart of the incense trade to the rise of Islam and eventual establishment of the Saudi kingdom.

“We are not closed,” says al-Ghabban. “We were always open. We are open today.”

Many of the pieces in the show are being seen for the first time in North America, after the show toured Paris, Barcelona, St. Petersburg and Berlin. The Sackler has partnered with the Commission to organize a North American tour, tentatively beginning in Pittsburgh before moving to Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts and San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum.

Sackler director Julian Raby calls it one of the museum’s most ambitious undertakings to date.

The show comes after the Metropolitan Museum of Art held its own exhibit, “Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition” in the spring. But rarely has a museum focused on the pre-Islamic roots of the region.

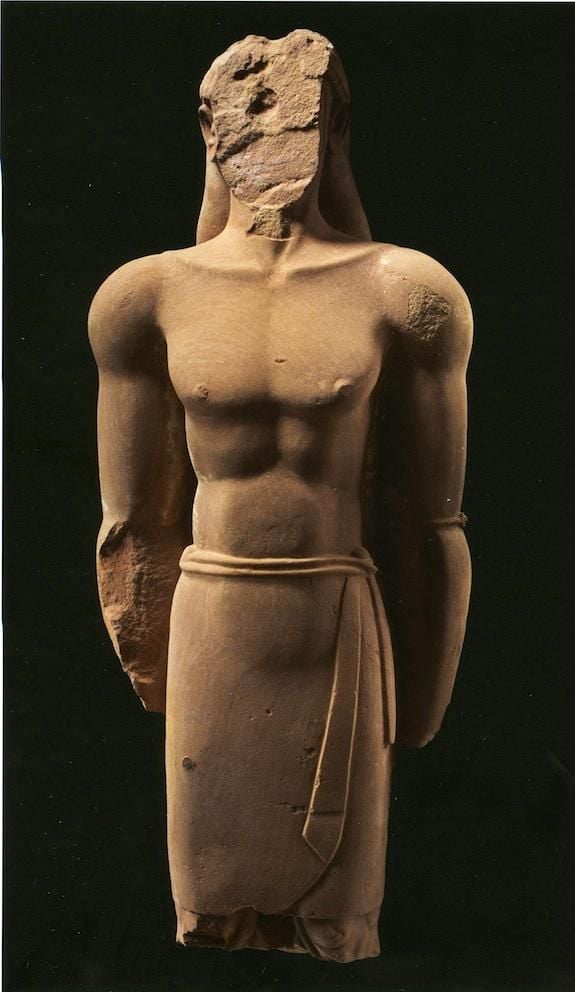

One of the show’s organizers in the United States, Sackler’s curator of Islamic art, Massumeh Farhad says, “It was practically all unfamiliar.” Though the items in the show, ranging from monumental sculptures excavated from temples to tombstones with some of the earliest known Arabic script, were discovered over the past several decades, many objects were just unearthed only in the past few years. “It’s new material that really sheds light on Arabia,” says Farhad, “which up to now everybody thought its history began with the coming of Islam, but suddenly you see there’s this huge chapter preceding that.”

Before Muslim pilgrims made their way to Mecca, Arabia was a network of caravan routes servicing the behemoth incense trade. It is estimated that the Romans alone imported 20 tons annually for use in religious and official ceremonies and even to perfume city sewage. “You forget what a smelly world it used to be,” Farhad jokes. Since incense–in the form of frankincense and myrrh–was only grown in southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa, traders had to travel through the peninsula, stopping to pay steep taxes at cities along the way. Though al-Ghabban tried to look past the pervasiveness of oil wealth in his country, the comparisons are hard not to notice (indeed, Exxon Mobil is even one of the show’s sponsors). “Incense was the oil of the ancient world,” explains Farhad.

As a result, the settlements, each with their own culture, grew wealthy and were able to both import goods and support a strong local artistic community, leaving behind a diverse material record. Enigmatic grave markers from Ha’il in the northwest, for example, share characteristics with those found in Yemen and Jordan. But, Farhad says, they’re distinct in dress and gesture. Some of the most stunning items in the show, the minimalistic rendering of human form speaks without translation to the sorrowful contemplation of death.

Other objects are already starting to challenge what were once historical truths. A carved figure of a horse, for example, includes slight ridges where the animal’s reins would have been–inconsequential except for the fact that researchers place the carving from around 7,000 B.C.E., thousands of years prior to earliest evidence of domestication from Central Asia. Though Farhad warns more research is needed, it could be the first of several upsets. “This particular object here is characteristic of the show in general,” says Farhad.

With the rise of Christianity, the luxurious expense of incense fell out of favor and over time the roads once traveled by traders were soon populated by pilgrims completing the Hajj to Mecca, where Muhammad famously smashed the idols at the Ka’ba. Because of Islam’s condemnation of idolatry, figural art was replaced by calligraphy and other abstracted forms. A room of tombstones that marked the graves of pilgrims who had completed the holy journey to Mecca represents some of the earliest known Arabic script. Lit dramatically, the rows of red and black stone mark a striking transition from the Roman bronzes from the 1st century C.E. just a few feet away.

In the exhibition catalog, Raby writes, “The objects selected for Roads of Arabia demonstrate that the Arabian Peninsula was not isolated in ancient times.” Through its role as a conduit for trade, Raby argues, Arabia supported a “cultural efflorescence.” By rethinking the region’s history, it seems Saudi Arabia, through the Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, also hopes for reconsideration as an open and dynamic country along the lines of this new picture now emerging of its past.

“Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” opens November 17 with a symposium titled, “Crossroads of Culture” and cultural celebration, Eid al Arabia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)