A Sports Curator at the Smithsonian Unpacks the Myths and Reality in the Film “Race”

Jesse Owens is best known for his performance at the 1936 Berlin Games, but curator Damion Thomas says there is more to the story

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/c2/23c2f037-eec7-46f1-b0c6-2fcf32fd5c10/u309844aacme.jpg)

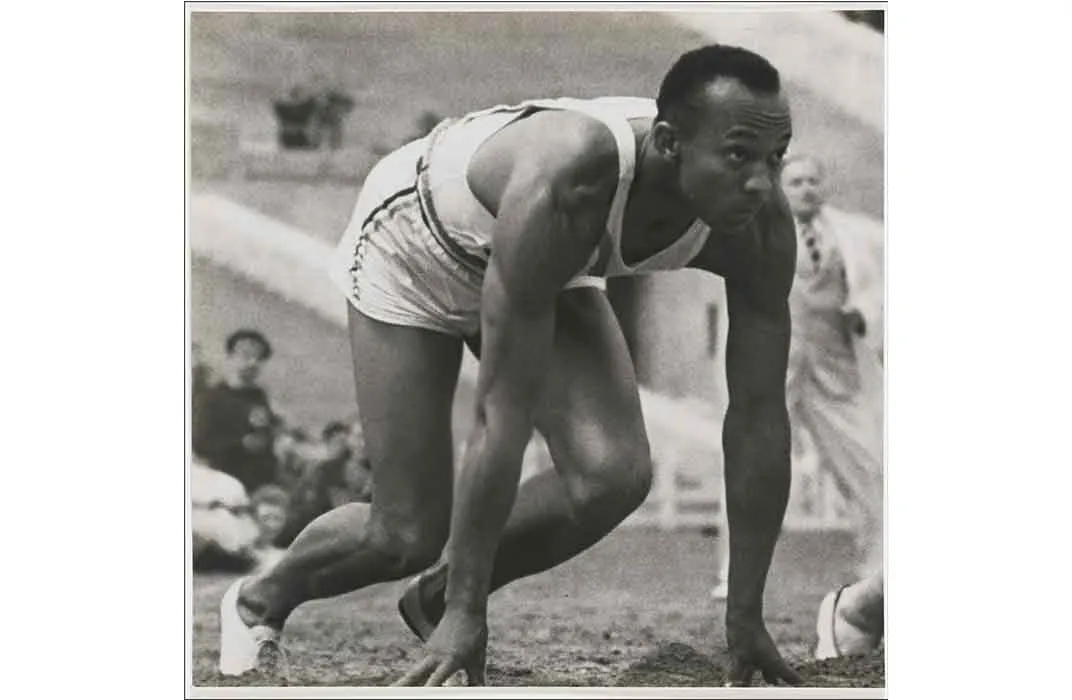

James “J.C.” Cleveland Owens was one of the fastest men to ever live. But as a black child growing up in Jim Crow America, Owens' future was far from set. Born into an impoverished family of sharecroppers in Oakville, Alabama, in 1913, when he was 5 years old, his mother had to remove a large lump on his chest with a kitchen knife because they couldn’t afford to take him for surgery. Owens survived the makeshift procedure, and went on to become a legend, winning four gold medals at the 1936 Nazi Olympics in Berlin, a feat that wouldn’t be matched for another 50 years, when Carl Lewis did the same at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

But there's more to Owens' story than his most famous moment. Indeed, Owens greatest athletic achievement wasn't even at the Olympics, it came a year before at the 1935 Big Ten Track and Field Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan. There, as an Ohio State sophomore, Jesse (his nickname the product of a teacher who once pronounced his name “Jey-See”) set four world records in the long jump, the 220-yard dash, the 220 low hurdles, and then tied the world record in the 100-yard dash in under an hour. He accomplished all of this, despite having injured his tailbone so badly before the race that he couldn’t bend over to touch his knees. It was a feat that Sports Illustrated dubbed the "Greatest 45 minutes ever in Sports."

Owens' life after the 1936 Olympics was no storybook tale, either. Following the Games, Owens struggled to capitalize on his fame, returning to a racially divided country that wanted to celebrate his accomplishments but not his skin color.

Smithsonian curator Damion Thomas, who oversees the sports collections at the National Museum of African American History, speaks with Smithsonian.com to unpack the myths and realities of one of the greatest Olympians of all time.

Talk to me about Jesse Owens' early life and the context around his family’s poverty

Jesse Owens is born in Alabama, and his family moves to Cleveland as part of the Great Migration, a number of African Americans who left the South during World War I looking for greater opportunities. Jesse Owens’ family were sharecroppers, which was a legalized way to keep African Americans tied to farms in the South.

It was a system in which you bought all of your food and clothing from the owners of these large plantations. They wouldn’t tell you how much it all cost; they wouldn’t tell you how much money you had in your account. Then they would take the cotton that you harvested that year, or the crops you harvested, they would take them to market and sell them, and then come back and tell you how much they sold them for.

So the people who actually did the work didn’t control the ability to take the items to market, and so what happened is that sharecropping families always got cheated. Somehow, they always still owed rent, owed for food and clothing and things like that. It was a system designed to keep African Americans tied to the land. And it was a system designed to keep them from having financial prosperity. That’s the plight of generations of African Americans who are tied to the South before they begin to move up North.

But the family still struggles once they move to Cleveland, right?

One of the reasons that Jesse Owens went to Ohio State is that they gave his dad a job. It’s a way for his dad to get some employment in a very harsh racial environment. I thought the film did a great job in not romanticizing the North but demonstrating the clear-cut ways that African Americans were still treated as second-class citizens. . . He was still operating in a very racist environment, even at a Big Ten university in the North, there were still tremendous challenges that African Americans faced though they were allowed to compete and attend. I thought, in many ways, that was one of the biggest strengths of the film, it didn’t romanticize his time at Ohio State.

Can you explain just how significant his 1935 performance at the Big Ten Track and Field Championships in Ann Arbor was?

It was an all-time historic event. To set so many world records in one meet, it’s something that you don’t see. It’s really interesting in the film that they have a clock and you can see the short timespan in which he accomplishes these amazing feats. I thought that was another one of the strengths of the film, it suggested how important this meet was and how dominant he was.

Jesse’s greatest competitor in the United States was Eulace Peacock, whom we meet in the film. How would you say the athletes stacked up against each other? Eulace did beat Jesse at an important meet. Is there a case to be made that Peacock was the more dominant athlete?

Eulace Peacock was a great track athlete. But we largely don’t know anything about him because he didn’t make the Olympic team. He didn’t compete, didn’t get a gold medal. I think it speaks to how significant the Olympics are for track and field athletes, and because he didn’t get a chance to compete, he’s become largely forgotten in our history. Peacock did beat him in an important race, but Jesse Owens has four gold medals. Peacock doesn’t have any. And that is the defining way we evaluate track and field athletes.

Tell me about track and field athletes in the 1930s. The sport enjoyed an incredible popularity in the United States

Track and field was a much bigger sport at that time. During this time, it’s all about amateur sports, they’re held in higher esteem than professional sports. Those sports were looked down upon. Track and field, collegiate basketball, collegiate football were considered the ultimate sporting spaces.

How did you feel about the film's portrayal of the United States Olympic Committee president and newly minted member of the International Olympic Committee Avery Brundage?

I think the film does an excellent job explaining how important Avery Brundage is to the U.S. Olympic Committee. He is the head of the committee for roughly 20 years, then he’s head of the IOC [International Olympic Committee] for an incredibly long time as well, about 20 years. You can make a case that Avery Brundge is one of the most significant people in Olympic history.

At the time, World War I was known as the Great War and people never thought they’d see a war that was so destructive. So here you are, roughly 15 years later looking at the prospect of going through that again, and a lot of people had lost family members and seen the destruction of families, societies, countries from that war and wanted to avoid it. There’s a level of appeasement that you see taking place. The film did a great job of showing Avery Brundage seeing the signs, seeing people being round up, seeing people being assaulted and treated less than others because they were Jews.

In some ways, it’s also a testament to Avery Brundage’s mistaken belief in the power of sports—this idea that sports are about peace, and sports can bring people together, and sports are a way to heal wounds. One important thing to remember about the 1936 Olympics is that one of the reasons Germany is awarded the Olympics is that it’s a way for nations around the world to welcome Germany back into its good graces. After that, Hitler comes to power and wants to use the Games for his own political purposes. So it’s a difficult time. And I think the film tried to wrestle with that difficult time.

Though Brundage does help push the United States to compete in the Berlin Games, the film shows how Jesse Owens was torn by the decision to attend. Can you describe the pressure he faced as he made his decision?

The scene where the representative from the NAACP comes to talk to him is a really important one because there was tremendous discussion in the African American community about whether African Americans should go compete. Particularly since it’s the Jews who are being persecuted.

The NAACP and other African American organizations had formed tremendous alliances with Jewish organizations and had been working together to solve these dual problems what was known as the “Negro question” and the “Jewish question” became a strong connection between African Americans and Jews fighting for equality. In fact, a couple of the founders of the NAACP were Jewish Americans and had been heavy financial supporters of the organization. So people saw this as an opportunity to return the favor and take a principled stand against Nazi Germany. It was a complicated situation where you’re asking an athlete to become a symbol of a larger struggle, and certainly there was lots of pressure on him and the other 17 African Americans who went to compete and had to make a decision on how to best use their platform.

As Race shows, Leni Riefenstahl films the Olympic Games. What was she trying to do and how does her work usher in a new era of Olympic competition?

Race does a great job of capturing her work, which is still one of the most important in film history in terms of her use of slow motion, of close ups, and different kinds of angles. It was her technical innovations that we see transform moviemaking, but also it’s her mythmaking and story production.

The Germans wanted to use the Berlin Games to suggest they were the heirs to the Greek empire, and the film is largely designed with that focus, that’s why you have the torch relay from Greece all the way to Berlin and into the stadium. The Berlin stadium up until that time is the most impressive stadium in the world and that speaks to the engineering prowess of Germany—to create this spectacle that the world comes to see.

The way she films this arena, and what it looks like is important. To this propaganda campaign, one of the things people often say is that Jesse Owens and his four gold medals destroyed the myth of Aryan supremacy, but that’s not how the Germans saw it. One, they saw the Olympic Games as suggesting that they were the heirs to the Greeks. And they do for a couple of reasons, number one is that they won more medals than anyone, so the Olympic Games still became a way for them to claim superiority.

The film doesn’t show Hitler meeting Jesse Owens after he wins his first medal, but there is a story that has persisted that Hitler refused to shake Owens’ hand. Can you talk about the fact or fiction around this handshake?

In terms of the handshake, what happened is that on the first day of competition Hitler shook the hands of all the German winners, and the Olympic officials went to him and said: you can’t do that. As the host, you just can’t shake hands with the German winners, you have to shake hands with all the winners.

It’s either one or the other, and Hitler decided he wouldn’t shake hands with any of the winners and it so happens that Jesse Owens wins the next day, and so that scene where Jesse Owens is taken up into the suite to shake Hitler’s hand is largely fiction because it wouldn’t have happened in that particular way.

One of the things that happened later is this myth of Hitler not shaking Jesse Owens’ hand becomes this story that people tell. And Jesse Owens, who struggled financially after the Olympic Games, would go on the banquet circuit and tell the story. It became this kind of moneymaking story for him. Because by depicting Hitler in that way, it was in some ways making America seem like a more open place to be.

In Germany, Jesse Owens befriends the German athlete Luz Long. Can you explain the significance of their friendship at the Games and afterward?

The thing about Jesse Owens is he was incredibly popular in Germany, and the German fans were very appreciative of him. The reason sports, particularly amateur sports were so important at that point, is that sports teach values, they teach character, they teach discipline, they teach collegiality, and we see Luz Long demonstrating that.

He becomes a symbol of a different Germany. You have Luz symbolizing Germany as a kind of compassionate empire, and Hitler representing the worst of Germany, so Luz becomes an important kind of person that helps balance out those depictions.

In some ways, what ultimately happens in German history is that Hitler becomes evil, but the German people were not. Jesse Owens gets invited back to Germany in the 1950s, he runs around the Berlin stadium track again and is celebrated. A large part of that is the German people trying to distance themselves from Hitler.

What does it mean for Jesse Owens to bring his unparalleled four gold medals home to the United States?

When Jesse Owens wins four gold medals, the meaning is complicated. What does that say about society and African Americans? Those are important questions that people want to engage. On one hand, you can say even with segregation, African Americans are able to achieve incredible heights, demonstrate incredible achievements, but what you also have to acknowledge is that American society is about defining African Americans as inferior.

If we go back to the early history of sports and why sports becomes popular in the United States, it is because sports reinforced intellectual ability. A healthy mind and a healthy body go together. That’s one of the reasons sports becomes such an important part of the educational system. What happens then when African Americans become the dominant athletes? What ultimately takes place is that meaning of sports starts to change.

Rather than athletic capacity and intellectual capacity being intimately tied, now people say it’s an inverse relationship. Jesse Owens is a dominant athlete because he’s more primitive, because African Americans have longer limbs. People argue that African Americans have more fast twitch muscles. There becomes a biological argument that explains why African Americans achieve in athletics, achieve in track and field. What happens is that even when Jesse Owens becomes a dominant athlete, arguably the best ever, this is still used to define African Americans as inferior.

What is it like for Jesse Owens to be an athletic superstar in a very racial divided America?

After 1936, Jesse Owens tries to capitalize on his athletic fame. He’s an athletic star, but part of the problem is he doesn’t get the opportunity to transcend into the status of celebrity. One of the things the film doesn’t deal with is the aftermath of Owens winning four gold medals. Jesse Owens wins four gold medals at the Olympic Games and the U.S. Olympic Committee has to pay back the expenses and so they go on a tour of Europe where they’re asked to run races in poor conditions. He competed in several events before the tour is over and then he says, I’m done, I’m not doing it, and he leaves.

Avery Brundage then suspends him from international competition. So here you have one of the biggest stars getting suspended from competing in amateur sports. That’s where things begin to change for Jesse Owens.

He gets involved in the presidential campaign and he tours with Al Smith. It’s a very unpopular decision for Jesse Owens to do that particularly when African Americans were largely supporting Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Then he comes back and how do you turn athletic success into money-making opportunities? Jesse Owens spent much of the 1940s working for the Harlem Globetrotters, where he would be an announcer and he would run around the track during half time.

He was involved in a number of dehumanizing activities, racing horses and things of that nature trying to earn a living. So it was tough for him to make a living.

In the 1960s, many African Americans become critical of Jesse Owens. Do you think this critique is fair or unfair?

One of the things that happened to a number of African Americans athletes, in particular Jesse Owens and Joe Lewis, is that by the 1960s, people begin to see their model of integration, particularly this idea of being a “good negro,” someone who doesn’t talk about race, being called a credit to their race because of the fact that they’re deferential, because they’re not rebel rousers.

By the late 1960s, you have a whole generation of athletes who have come into the NBA, the NFL and to other sports. By the late 1960s, the black presence in sports is firmly established and then those athletes begin to look back at earlier generations and sort of critique them for their willingness to kind of be humble and deferential.

And it’s unfair because each generation has its own struggle, each generation has its own battles to fight and so to look at an earlier generation of athletes and critique them because they’re not fighting the battles of your generation is simply unfair.

Is there anything else you noticed in the film that you’d like to discuss?

Yes, there is one thing. The film doesn’t do a good job of discussing Owens in relation to the other 17 African Americans that competed in the 1936 Olympics. Jesse becomes the one racial representative when there were some incredible athletes there. Ralph Metcalfe went on to a distinguished career in Congress, James LuValle went on to a distinguished career, and others. I think the emphasis on Jesse Owens obscures the fact that he was part of a larger contingent, and the significance of that group of athletes is often lost by the focus on Jesse.

Last question, overall, how do you think that Race did tacking the dual meaning in its title?

I think that one of the problems with Hollywood is it often wants to end its films with a triumphant story. Certainly, Jesse Owens has a triumphant moment at the 1936 Olympics, but it’s quickly washed away when he gets banned from amateur competition, and his inability to secure a solid financial future.

He lives a really difficult existence, gets in tax trouble with the IRS. I don’t know that we got a full story about what winning meant and didn’t mean for Jesse Owens. It’s interesting that at the end of the film we see Jesse Owens going to the Waldorf Astoria in New York. That is a perfect ending to the film because he’s being honored, but he’s got to go through the back door. That is a perfect metaphor for the experiences of African Americans through much of the early- to mid-20th century.