For Susan B. Anthony, Getting Support for Her ‘Revolution’ Meant Taking on an Unusual Ally

Suffragists Anthony and Cady Stanton found common cause in a wealthy man named George Francis Train who helped to fund their newspaper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/83/c783ac89-6b6d-462a-842c-e1bafa2958a6/nmahjn20131553web.jpg)

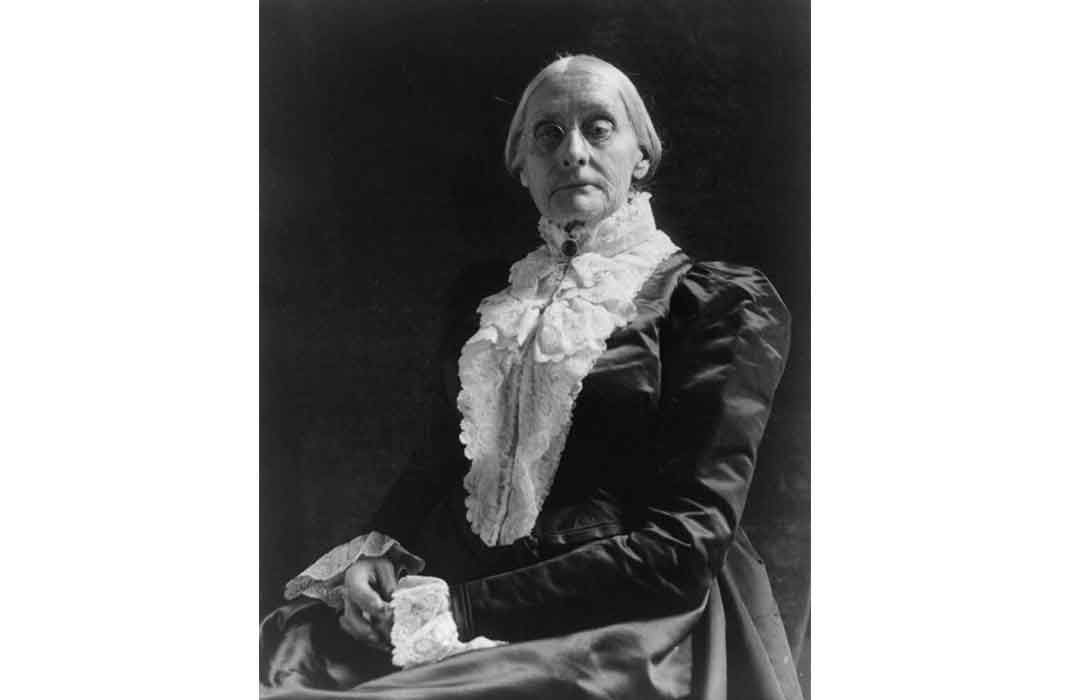

Tucked carefully away in a storage cabinet at the National Museum of American History, there is an old-fashioned inkstand bearing a story that must be told from time to time. It once sat on the desk of Susan B. Anthony and dispensed the ink that she used to produce a newspaper that few remember today.

Before the spread of the ballpoint pen, an inkstand was an essential tool for any writer. It held an inkwell, a shaker of sand used to blot dry the ink, and a compartment with a little drawer to store the steel nibs that served as the tip of the pen. This particular inkstand is dark, almost black. Its lines are feminine and strong, much like its original owner.

Lecturer, organizer, author and lobbyist for the rights of women, Susan B. Anthony was also the proprietor of a radical newspaper, which was controversial, financially unsuccessful, but never boring.

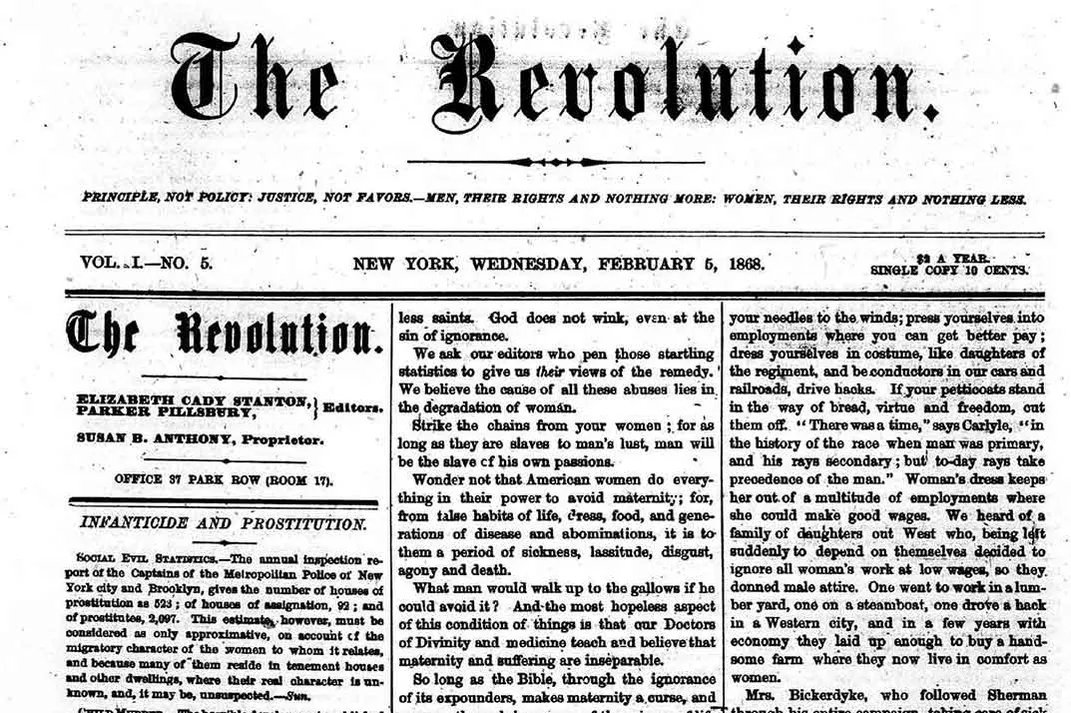

With her fellow women's suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton serving as editor, Anthony spent more than two years putting out a 16-page weekly paper appropriately titled The Revolution.

The year was 1868. The Civil War had ended only a few years before. Women could not vote. Once married, they could not hold property or file lawsuits. They could rarely obtain divorces, even when abused.

Blacks had been freed but they too couldn't vote. President Andrew Johnson, sworn in following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was about to be impeached for bungling the legalities of reconstruction.

Susan Anthony lived at a time when cheap rum and whiskey made one in every five husbands an alcoholic. Cigar smoke filled the air in every public place and the slimy brown stains of tobacco spit dotted streets and even floors and walls where (mostly male) tobacco chewers had missed the spittoon.

Throughout the Civil War, the women's suffrage movement had been more or less on pause. Women had found new economic opportunities during the war, but as they did after World War II, those disappeared once the war ended. “It's like Rosie the Riveter and then Rosie being sent home because the returning veterans need their jobs back,” says Ann Dexter Gordon, a research professor of history at Rutgers University and the editor of the Elizabeth Cady Standon and Susan B. Anthony Papers. “There's a lot of pushing women back after the Civil War.”

Anthony wanted to see the cause of women's suffrage rise up again. Part of her vision for how to do this was to start a newspaper. But she didn't have the money; that is, until she met one of the strangest and most colorful characters of the era—George Francis Train, who one historian once described as “a combination of Liberace and Billy Graham.”

Dapper, polished and always freshly shaved and scented with cologne, Train carried a cane for effect rather than need. But he never touched alcohol or tobacco. One assumes Anthony would have appreciated that.

Train was wealthy, too. He had made his first real money as a teenager by organizing a line of clipper ships that carried would-be gold miners from Boston to San Francisco. He went on to amass a moderate fortune by betting on the success of railroads along routes that most other investors didn't consider viable.

He ran for President against Lincoln in 1864, but no votes in his favor were recorded. While running again for President in 1868, he made a trip around the world in 80 days and was apparently the inspiration for the character of Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne's novel, Around the World in Eighty Days.

But Train was also passionate about other issues, which it isn't clear that Anthony shared. He was a supporter of the Fenian movement. The Fenians were Irish immigrants who opposed English occupation of Ireland and formed an army within the U.S. with the aim of invading Canada to force England to pull out of Ireland (a series of five armed raids were actually attempted). Train was also a proponent of the controversial greenback monetary system, an early form of the modern fiat (rather than gold-backed) currency that the U.S. uses today.

Train claimed to have invented perforated stamps, erasers attached to pencils and canned salmon, but he was also a devoted and effective supporter of women's suffrage and the temperance movement to ban alcohol. Anthony and Stanton found common cause with him (though he believed that blacks should not be given the vote until they had been taught to read) and he became the principal funder of their newspaper.

While traveling together on a speaking tour in Kansas the three became great friends and Anthony found his limitless energy a source of personal strength and inspiration. She credited him with the 9,000 votes in support of a women's suffrage amendment (that was a lot of votes in the sparsely-populated new state).

“Something happened so that she is bound to him for the rest of her life,” says Gordon. “One of the entries she makes somewhere is something like 'at a moment when I didn't think anything of myself, he taught me my worth.' And it just seemed to me that something happened on that trip that was an identity crisis and Train pulled her through.”

The first issue of their newspaper was distributed on January 8, 1868. In its pages, Anthony, Stanton, Train and a few other writers imagined and advocated for a world entirely different from the cruel one outside of their New York City office door. They all shared frustration over the apparent limits of what had been accomplished in the wake of the Civil War. “Men talk of reconstruction on the basis of 'negro suffrage,'” wrote Stanton, “while multitudes of facts on all sides. . . show that we need to reconstruct the very foundations of society and teach the nation the sacredness of all human rights.”

Neither Anthony nor Stanton were simply women's suffragists; they wanted to change their whole society—a revolution.

At the highest levels of government, they sought dramatic change. “That the President should be impeached and removed, we have never denied,” the paper wrote of President Andrew Johnson, who was indeed impeached but not removed from office.

They wrote of a plan to demand that Ireland be ceded by Britain to the United States in settlement of a debt. “That generation was brought up, they knew Revolutionary War veterans,” says Gordon. “It's easier for some of them to be open to the Irish revolt than we might think, because it was against England!”

The paper opposed sentencing criminals to whippings and beatings. In a speech reprinted by The Revolution while he was running for President as an independent, Train declared: “I intend to have all boys between 18 and 21 vote in 1872. Young men who could fire a bullet for the Union should be allowed to throw a ballot for their country.” He was only about a century ahead of his time. Voting rights for adults between 18 and 21 were not granted until ratification of the 26th Amendment in 1971.

Prohibition of alcohol was wound tightly into The Revolution’s ideology. Alcohol was seen as a corrupting force that caused men to abuse their wives. Banning alcohol was viewed as a way to stop the abuse. Women's suffrage, it followed, would lead to prohibition, which for those inclined to imbibe, was a common reason to oppose suffrage.

One exception was Jack London, who later wrote in the opening chapter of his book, John Barleycorn—about his excessive drinking habits—of the 1912 ballot for a women's suffrage amendment. “I voted for it,” London wrote. “When the women get the ballot, they will vote for prohibition. . . It is the wives, and sisters, and mothers, and they only, who will drive the nails into the coffin.” It was the only way that he could imagine stopping his alcoholism.

The women's suffrage movement in the U.S. arguably blossomed from the success of the abolitionist movement against slavery in the earlier part of the century.

Anthony was born into a New England family of Quakers and was raised around vocal opposition to slavery. Every Sunday, Frederick Douglass was a guest at her father's farm among a group of local abolitionists in Rochester, New York. Most of the major figures in the women's suffrage movement after the Civil War had been vocal abolitionists. But a rift opened up when debate began over what would eventually become the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. The Amendment prohibited denial of the right to vote based on a persons “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Many suffragists, including Stanton and Anthony, felt betrayed by their cohorts for a compromise that left women without the right to vote.

By 1869, Anthony found herself butting heads with her old friend, Frederick Douglass. “I must say that I do not see how any one can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro,” Douglass said during an 1869 debate.

Anthony responded saying, “if you will not give the whole loaf of justice to the entire people, if you are determined to give it to us piece by piece, then give it first to women to the most intelligent and capable portion of the women at least, because in the present state of government it is intelligence, it is morality which is needed.”

It wasn't just a question of waiting for their turn. Anthony and other activists were concerned that universal male suffrage would damage the odds of women's suffrage ever happening. While white men had been exposed somewhat to the arguments in favor of women's rights for years, the men who would be newly enfranchised by the 15th Amendment had not been. Former slaves, prohibited by law from being taught to read, could not have read the suffragists' pamphlets and newspapers. They were expected to vote against women if given the ballot, as were the Chinese immigrants who had begun to pour into California.

As a Congressional vote on the 15th Amendment loomed, the division between women's rights advocates and the rest of the abolitionist community deepened. The rift would eventually tear the women's suffrage movement into two disparate camps that would not reunite for decades.

Anthony and Stanton, both already major national figures and leaders, found that their authority across the movement had been compromised in part because of The Revolution. Specifically, because of the involvement of George Francis Train.

In a letter which was published by The Revolution, William Lloyd Garrison (a founder of The American Anti-Slavery Society, and editor of another newspaper) wrote: “Dear Miss Anthony, In all friendliness and with the highest regard for the Woman's Rights movement, I can not refrain from expressing my regret and astonishment that you and Mrs. Stanton should have taken such leave of good sense, and departed so far from true self-respect, as to be travelling companions and associate lecturers with that crack-brained harlequin and semi-lunatic, George Francis Train! . . .He may be of use in drawing an audience but so would a kangaroo, a gorilla, or a hippopotamus...”

Garrison was not alone. Old friends snubbed them, in some cases literally refusing to shake hands. Train was a problem as well as a blessing. Eventually, they announced that he was no longer associated with the paper.

In practice he was still writing uncredited material in almost every issue, usually about fiscal policy and his surprisingly prescient vision of a system of greenbacks that would be “legal tender for all debts, without exception.” But between Train's history of involvement in The Revolution and Anthony's stance against the Fifteenth Amendment, serious damage had been done.

A list of delegates was released in October of 1869 for a convention to establish the brand new American Woman Suffrage Association. The Revolution commented in its October 29th edition, “Where are those well-known American names, Susan B. Anthony, Parker Pillsbury, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton? Not one of them appears. In fact, it is clear that there is a division in the ranks of the strong-minded, and that an effort is to be made to ostracise The Revolution...”

Anthony struggled to keep the paper afloat, but without constant new infusions of cash from Train she couldn't make ends meet. Half of her potential subscribers had shunned her. The income from ads for sewing machines, life insurance and (ironically) corsets wasn't enough, either. The Revolution was sold to new proprietors and eventually folded completely.

“It did amazing things while it was going on,” says Gordon. “They're meeting with people who were in the First International with Karl Marx. They are in touch with white and black reconstruction people in the south. . . . They have a British correspondent. There's letters coming in from Paris. If the money had come in, could they have kept this up? What would have happened?”

Train shrugged off the end of the newspaper and returned to his favorite pastime by launching his third campaign for President as an independent candidate in 1872. No votes were recorded for him. His businesses crumbled. He went bankrupt and embarked on a strange campaign of speeches and articles to become Dictator of the United States.

Anthony, Train, Stanton and The Revolution had wanted everything to change all at once and right away. Some of those ideas were successful and others were not. Prohibition didn't work out as planned and Ireland is still part of Britain. President Johnson survived impeachment and finished his term of office. But spittoons have disappeared from the floors of every room, people of all races have equal rights under the law, and George Train got his system of greenbacks.

In 1890, the American Woman Suffrage Association buried the hatchet with Anthony and merged with her rival National Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony died in 1906, beloved by millions of men and women alike but still trapped in a world that made no sense to her. It wasn't until 1920 that women were empowered to vote by the passage of the 19th Amendment. Shortly after the Amendment was fully ratified, The National American Woman Suffrage Association packed up a collection of relics associated with Anthony and the history of the movement. The collection was sent to The Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. It included Anthony's iconic red shawl and the inkstand that had she'd reached for every day at The Revolution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)