Teddy Roosevelt’s Epic (But Strangely Altruistic) Hunt for a White Rhino

In a new book, a Smithsonian naturalist tells the gritty, controversial tale of how one of America’s presidents felled a threatened species

“I speak of Africa and golden joys.” The first line of Theodore Roosevelt’s own retelling of his epic safari made it clear that he saw it as the unfolding of a great drama, and one that might have very well led to his own death, for the quoted line is from Shakespeare, the Henry IV scene in which the death of the king was pronounced.

As a naturalist, Roosevelt is most often remembered for protecting millions of acres of wilderness, but he was equally committed to preserving something else—the memory of the natural world as it was before the onslaught of civilization. To him, being a responsible naturalist was also about recording the things that would inevitably pass, and he collected specimens and wrote about the life histories of animals when he knew it might be the last opportunity to study them extant. Just as the bison in the American West had faded, Roosevelt knew that the big game of East Africa would one day exist only in vastly diminished numbers. He had missed his chance to record much of the natural history of wild bison, but he was intent on collecting and recording everything possible while on his African expedition. Roosevelt shot and wrote about white rhinos as if they might someday be found only as fossils.

Interestingly, it was the elite European big-game-hunting fraternity that most loudly condemned Roosevelt’s scientific collecting. He had personally killed 296 animals, and his son Kermit killed 216 more, but that was not even a tenth of what they might have killed had they been so inclined. Far more animals were killed by the scientists who accompanied them, but those men escaped criticism because they were mostly collecting rats, bats, and shrews, which very few people cared about at the time. Roosevelt cared deeply about all these tiny mammals, too, and he could identify many of them to the species with a quick look at their skulls. As far as Roosevelt was concerned, his work was no different from what the other scientists were doing—his animals just happened to be bigger.

In June 1908, Roosevelt approached Charles Doolittle Walcott, the administrator of the Smithsonian Institution, with an idea:

As you know, I am not in the least a game butcher. I like to do a certain amount of hunting, but my real and main interest is the interest of a faunal naturalist. Now, it seems to me that this opens up the best chance for the National Museum to get a fine collection, not only of the big game beasts, but of the smaller animals and birds of Africa; and looking at it dispassionately, it seems to me that the chance ought not to be neglected. I will make arrangements in connection with publishing a book which will enable me to pay for the expenses of myself and my son. But what I would like to do would be to get one or two professional field taxidermists, field naturalists, to go with us, who should prepare and send back the specimens we collect. The collection which would thus go to the National Museum would be of unique value.

The “unique value” Roosevelt was referring to, of course, was the chance to acquire specimens shot by him—the president of the United States. Always a tough negotiator, Roosevelt put pressure on Walcott by mentioning that he was also thinking about posing his offer to the American Museum of Natural History in New York—but that, as president, he felt it was only appropriate that his specimens go to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Compared to those of other museums, the Smithsonian’s African-mammal collection was paltry back then. The Smithsonian had sent a man to explore Kilimanjaro in 1891 and another to the eastern Congo, but the museum still held relatively few specimens. Both the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum in New York had been sending regular expeditions to the continent, bringing home thousands of African specimens. Eager not to fall farther behind, Walcott took up Roosevelt’s offer and agreed to pay for the preparation and transport of specimens. He also agreed to set up a special fund through which private donors could contribute to the expedition. (As a public museum, the Smithsonian’s budget was largely controlled by Congress, and Roosevelt worried that politics might get in the way of his expedition—the fund solved this sticky issue).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/fe/5bfee68e-b65e-42cb-84e4-3a99d00fa608/sia201400109web.jpg)

As far as Walcott was concerned, the expedition was both a scientific and a public-relations coup. Not only would the museum obtain an important collection from a little-explored corner of Africa, but the collection would come from someone who was arguably one of the most recognized men in America—the president of the United States. Under the aegis of the Smithsonian Institution, Roosevelt’s proposed safari had been transformed from a hunting trip to a serious natural-history expedition promising lasting scientific significance. An elated Roosevelt wrote British explorer and conservationist Frederick Courteney Selous to tell him the good news—the trip would be conducted for science, and he would contribute to the stock of important knowledge being accumulated on the habits of big game.

Roosevelt saw the trip as perhaps his “last chance for something in the nature of a great adventure,” and he devoted the last months of his lame-duck presidency to little other than making preparations. Equipment needed to be purchased, routes mapped, guns and ammo selected. He admitted that he found it very difficult to “devote full attention to his presidential work, he was so eagerly looking forward to his African trip.” Having studied the accounts of other hunters, he knew that the Northern Guaso Nyiro River and the regions north of Mount Elgon were the best places to hunt, and that he had to make a trip to Mount Kenya if he was to have any chance at getting a big bull elephant. He made a list of animals he sought, ordering them by priority: lion, elephant, black rhinoceros, buffalo, giraffe, hippo, eland, sable, oryx, kudu, wildebeest, hartebeest, warthog, zebra, waterbuck, Grant’s gazelle, reedbuck, and topi. He also hoped to get up into some of the fly-infested habitats of northern Uganda in search of the rare white rhino.

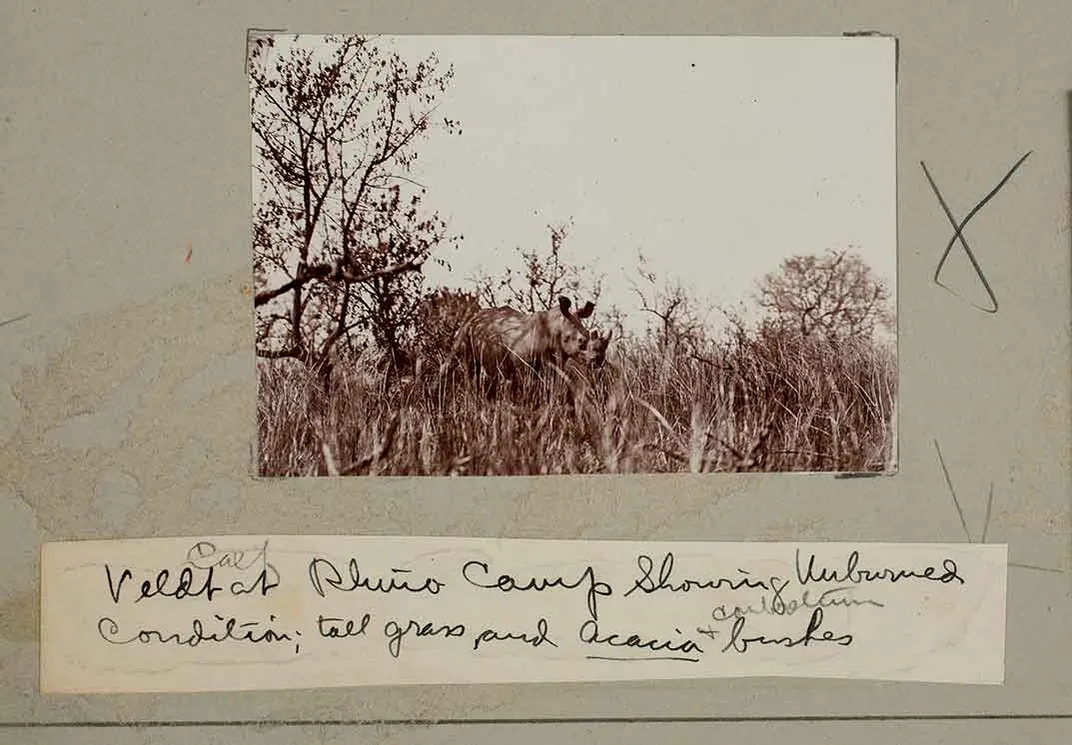

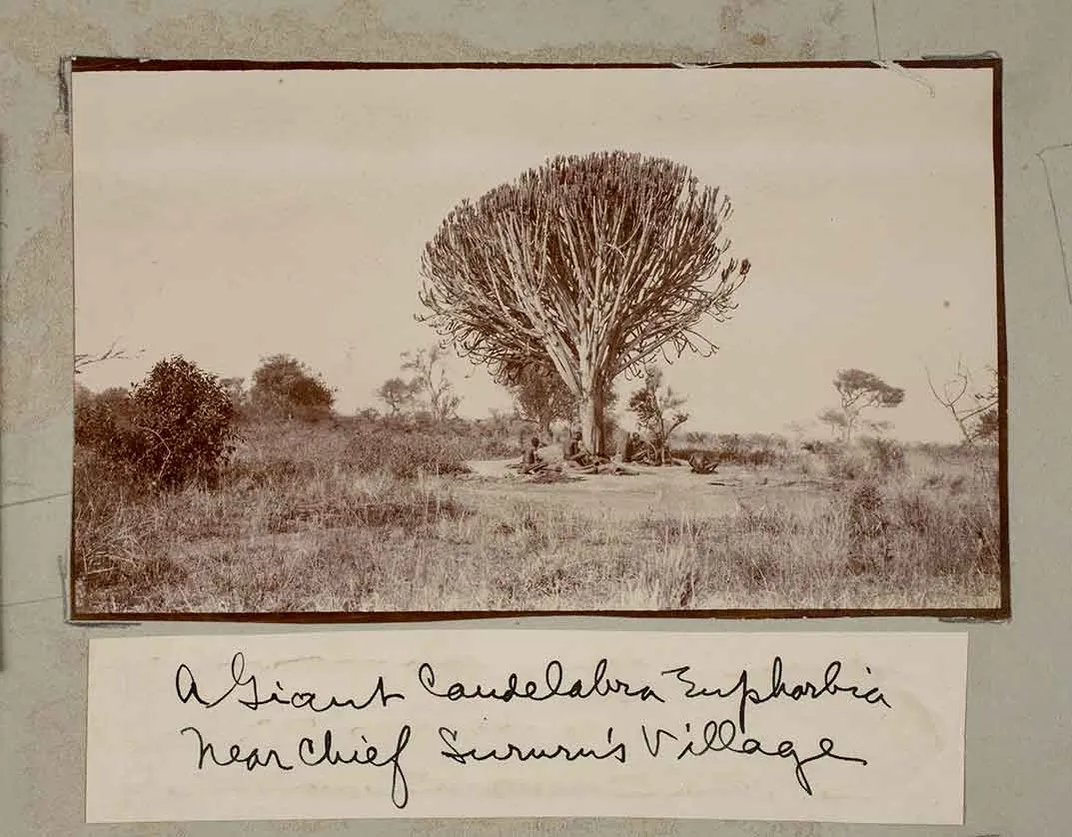

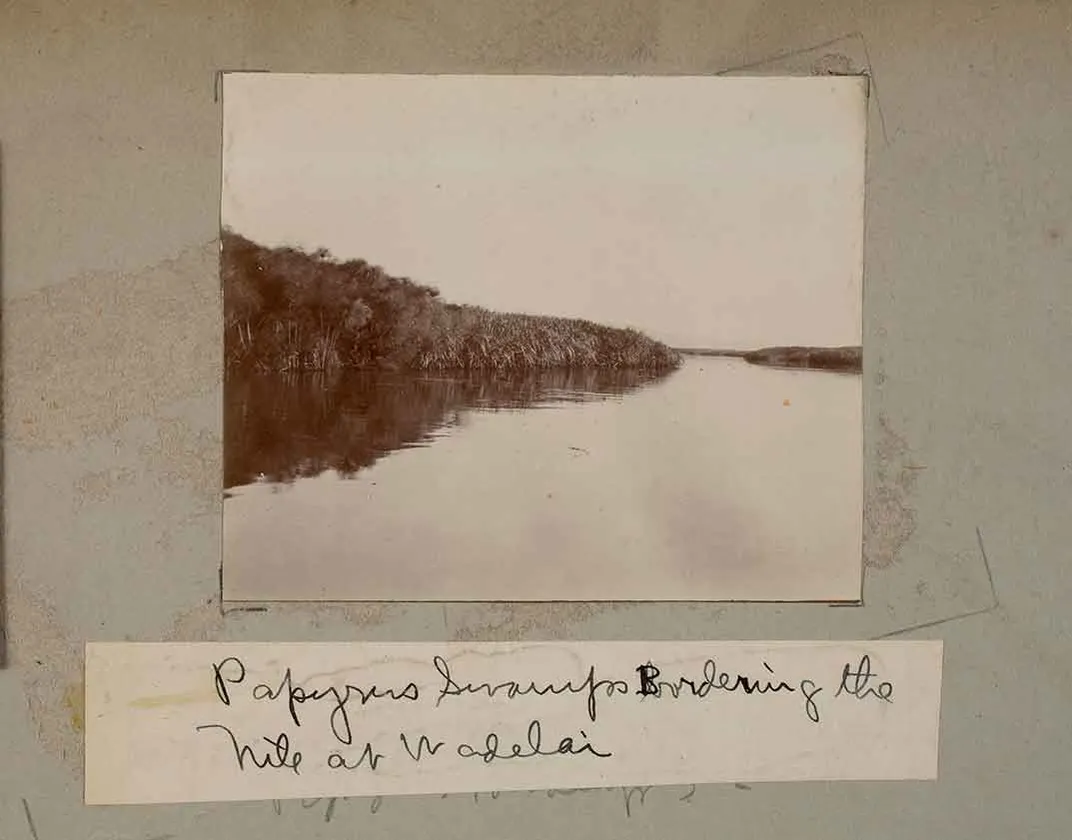

As 1909 drew to a close, he prepared to embark on a most dangerous mission. Disbanding his foot safari on the shores of Lake Victoria, he requisitioned a flotilla of river craft—a “crazy little steam launch,” two sailboats, and two rowboats—to take him hundreds of miles down the Nile River to a place on the west bank called the Lado Enclave. A semiarid landscape of eye-high elephant grass and scattered thorn trees, it was the last holdout of the rare northern white rhinoceros, and it was here that Roosevelt planned to shoot two complete family groups—one for the Smithsonian’s National Museum, and another that he had promised to Carl Akeley, the sculptor and taxidermist working on the African mammal hall at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Nestled between what was then the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the Belgian Congo, the Lado Enclave was a 220-mile-long strip of land that was the personal shooting preserve of Belgium’s King Leopold II. By international agreement, the king could hold the Lado as his own personal shooting preserve on the condition that, six months after his death, it would pass to British-controlled Sudan. King Leopold was already on his deathbed when Roosevelt went to East Africa, and the area reverted to lawlessness as elephant poachers and ragtag adventurers poured into the region with “the greedy abandon of a gold rush.”

Getting to the Lado, however, required Roosevelt to pass through the hot zone of a sleeping-sickness epidemic—the shores and islands at the northern end of Lake Victoria. Hundreds of thousands of people had recently died of the disease, until the Uganda government wisely evacuated the survivors inland. Those who remained took their chances, and Roosevelt noted the emptiness of the land.

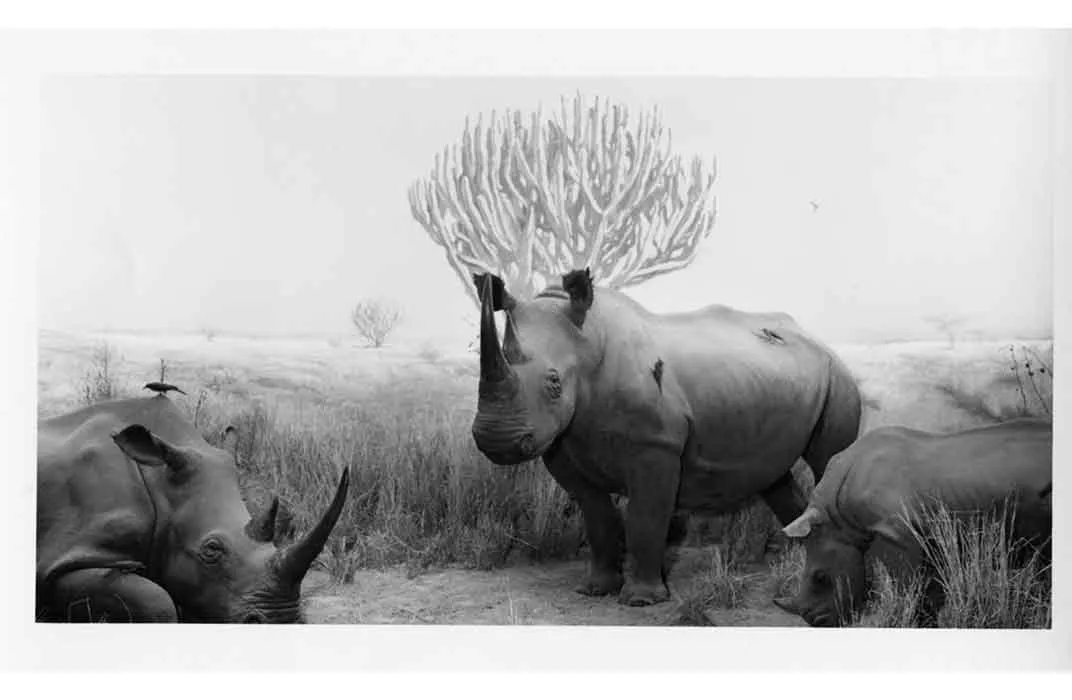

The white rhino lived there—a completely different species from the more common black rhino Roosevelt had been collecting. Color, though, actually has little to do with their differences. In fact, the two animals are so different that they are usually placed in separate genera. The white rhino—white being the English bastardization of the Afrikaans word wyd for “wide,” in reference to this species’ characteristically broad upper lip—is specialized for grazing. By comparison, the more truculent black rhino has a narrow and hooked upper lip specialized for munching on shrubs. Although both animals are gray and basically indistinguishable by color, they display plenty of other differences: the white rhino is generally bigger, has a distinctive hump on its neck, and boasts an especially elongated and massive head, which it carries only a few inches from the ground. Roosevelt also knew that of the two, the white rhino was closest in appearance to the prehistoric rhinos that once roamed across the continent of Europe, and the idea of connecting himself to a hunting legacy that spanned millennia thrilled him.

For many decades since its description in 1817, the white rhino was known to be found only in that part of South Africa south of the Zambezi River, but in 1900 a new subspecies was discovered thousands of miles to the north, in the Lado Enclave. Such widely separated populations were unusual in the natural world, and it was assumed that the extant white rhinos were the remnants of what was once a more widespread and contiguous distribution. “It is almost as if our bison had never been known within historic times except in Texas and Ecuador,” Roosevelt wrote of the disparity.

At the time of Roosevelt’s expedition, as many as one million black rhino still existed in Africa, but the white rhino was already nearing extinction. The southern population had been hunted to the point that only a few individuals survived in just a single reserve, and even within the narrow ribbon of the Lado Enclave, these rhinos were found only in certain areas and were by no means abundant. On the one hand, Roosevelt’s instincts as a conservationist told him to refrain from shooting any white rhino specimens “until a careful inquiry has been made as to its numbers and exact distribution.” But on the other hand, as a pragmatic naturalist, he knew that the species was inevitably doomed and that it was important for him to collect specimens before it went extinct.

As he steamed down the Nile, Roosevelt was followed by a second expedition of sorts, led by a former member of the British East Africa Police. But Captain W. Robert Foran was not intent on arresting Roosevelt—whom he referred to by the code name “Rex”; rather, he was the head of an expedition of the Associated Press. Roosevelt let Foran’s group follow at a respectable distance, by now wanting regular news to flow back to the United States. Foran had also been instrumental in securing a guide for Roosevelt on his jaunt into the virtually lawless Lado Enclave. The guide, Quentin Grogan, was among the most notorious of the elephant poachers in the Lado, and Roosevelt was chuffed to have someone of such ill-repute steering his party.

Grogan was still recovering from a boozy, late-night revel when he first met Roosevelt. The poacher thought [the president’s son] Kermit was dull, and he deplored the lack of alcohol in the Roosevelts’ camp. Among some other hangers‑on eager to meet Roosevelt was another character—John Boyes, a seaman who, after being shipwrecked on the African coast in 1896, “went native” and was so highly regarded as an elephant hunter there that he was christened the legendary King of the Kikuyu. Grogan, Boyes, and a couple of other unnamed elephant hunters had gathered in the hope of meeting Roosevelt, who characterized them all as “a hard bit set.” These men who faced death at every turn, “from fever, from assaults of warlike native tribes, from their conflicts with their giant quarry,” were so like many of the tough cowpunchers he had encountered in the American West—rough and fiercely independent men—that Roosevelt loved them.

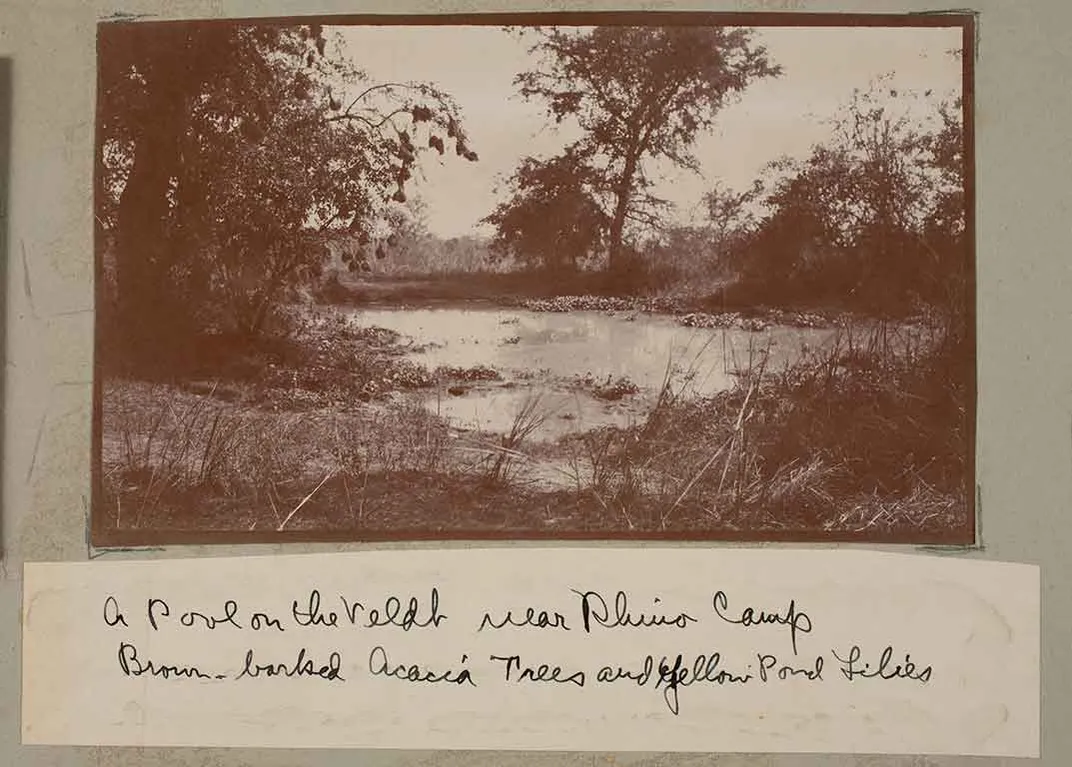

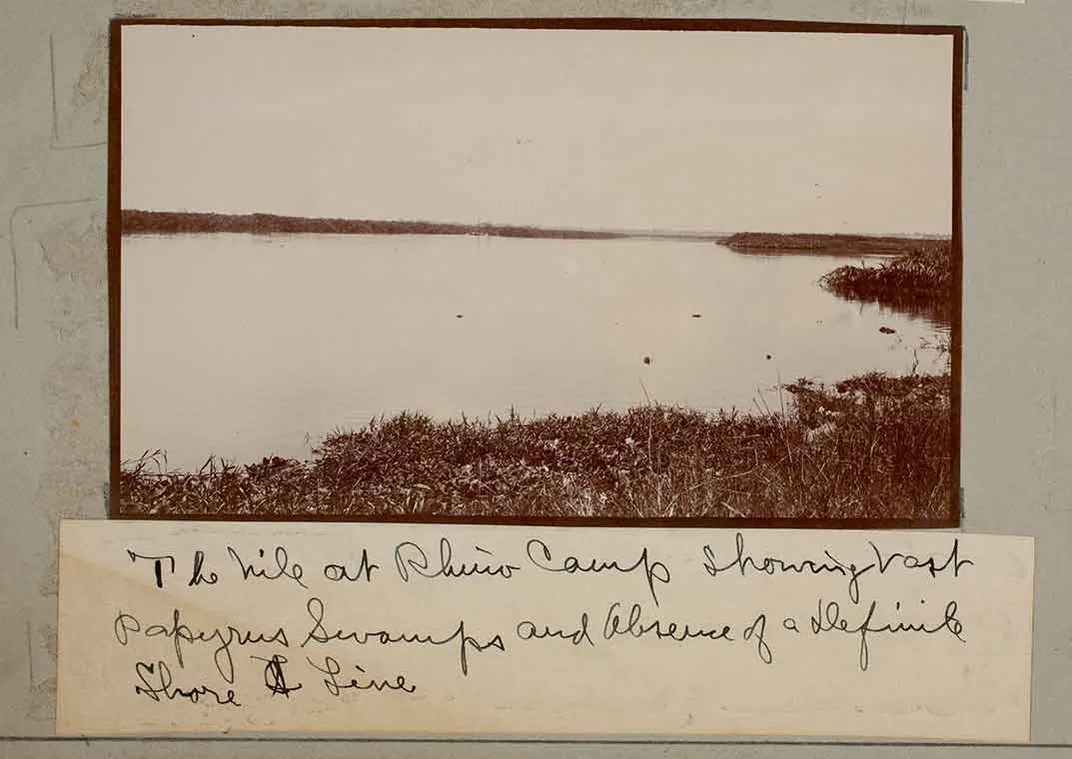

Downriver they went, past walls of impenetrable papyrus, until they came upon a low, sandy bay that is to this day marked on maps as “Rhino Camp.” Their tents pitched on the banks of the White Nile, about two degrees above the equator, Roosevelt was in “the heart of the African wilderness.” Hippos wandered dangerously close at night, while lions roared and elephants trumpeted nearby. Having spent the past several months in the cool Kenyan highlands, Roosevelt found the heat and swarming insects intense, and he was forced to wear a mosquito head net and gauntlets at all times. The group slept under mosquito nets “usually with nothing on, on account of the heat” and burned mosquito repellent throughout the night.

Although their camp was situated just beyond the danger zone for sleeping sickness, Roosevelt was still bracing himself to come down with some sort of fever or another. “All the other members of the party have been down with fever or dysentery; one gun bearer has died of fever, four porters of dysentery and two have been mauled by beasts; and in a village on our line of march, near which we camped and hunted, eight natives died of sleeping sickness during our stay,” he wrote. The stakes were certainly high in Rhino Camp, but Roosevelt would not have taken the risk if the mission was not important—the white rhino was the only species of heavy game left for the expedition to collect, and, of all the species, it was the one the Smithsonian would likely never have an opportunity to collect again.

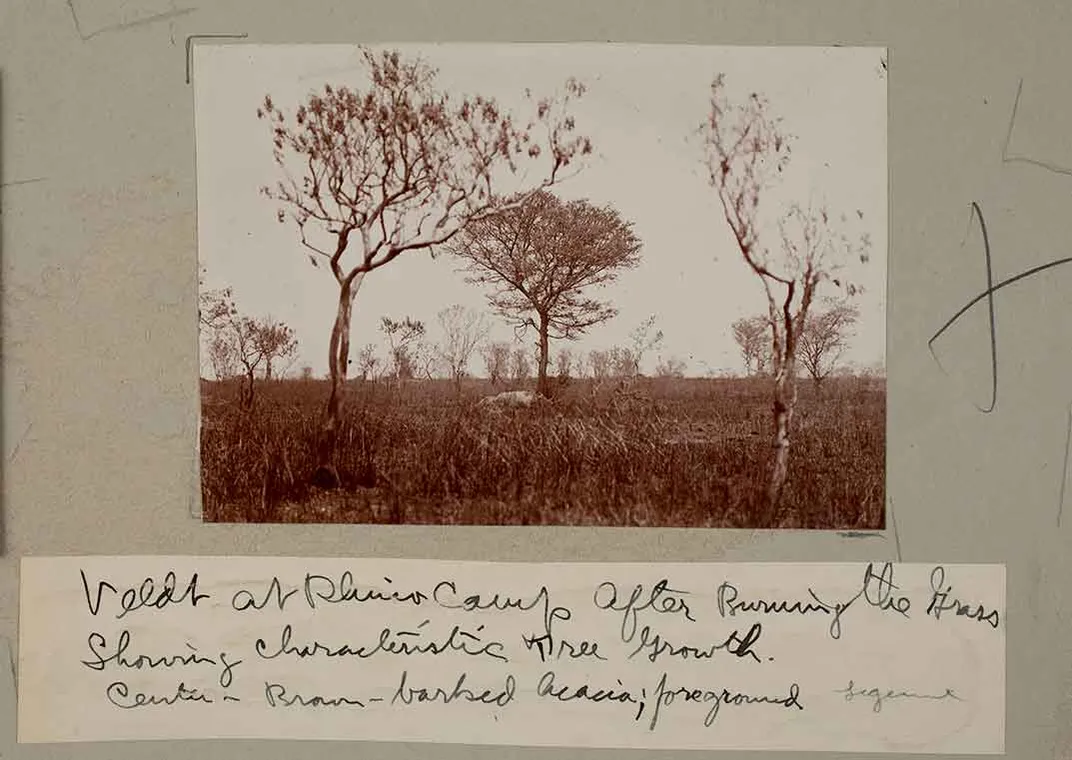

In the end, Roosevelt shot five northern white rhinoceros, with Kermit taking an additional four. As game, these rhinos were unimpressive to hunt. Most were shot as they rose from slumber. But with a touch of poignancy, the hunts were punctuated with bouts of wildfire-fighting, injecting some drama into one of Roosevelt’s last accounts from the field. Flames licked sixty feet high as the men lit backfires to protect their camp, the evening sky turning red above the burning grass and papyrus. Awakening to a scene that resembled the aftermath of an apocalypse, the men tracked rhino through miles of white ash, the elephant grass having burned to the ground in the night.

Whether the species lived on or died out, Roosevelt was emphatic that people needed to see the white rhinoceros. If they couldn’t experience the animals in Africa, at least they should have the chance to see them in a museum.

Today, the northern white rhino is extinct in the wild and only three remain in captivity. One of the Roosevelt white rhinos is view, along with 273 other taxidermy specimens, in the Smithsonian’s Hall of Mammals at on the National Museum of Natural History.

Adapted from THE NATURALIST by Darrin Lunde. Copyright © 2016 by Darrin Lunde. Published by Crown Publishers, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Darrin Lunde, is a mammal scholar who has named more than a dozen new species of mammals and led scientific field expeditions throughout the world. Darrin previously worked at the American Museum of Natural History, and is currently a supervisory museum specialist in the Division of Mammals at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. Darrin independently authored this book, The Naturalist, based on his own personal research. The views expressed in the book are his own and not those of the Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/31/6431907d-5678-4a2d-9146-9d5b7565f5a0/sia2016009164web.jpg)