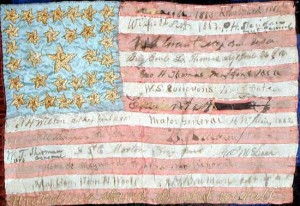

The Civil War 150 Years: Lord’s Famous Autograph Quilt

A Civil War teenager covers her quilt with the signatures of Union leaders

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111025114003quilt-small.jpg)

As part of the ongoing 150th anniversary of the Civil War at the Smithsonian Institution, the Around the Mall team will be reporting in a series of posts on some of the illustrative artifacts held by the museums from that epic battle. See more from the collections here.

In 1860, with South Carolina threatening to secede and the nation on the brink of civil war, a Nashville teenager named Mary Hughes Lord started making a quilt.

She wrote, “the day Tenn. seceded I stitched the U.S. Flag in the center of the quilt, my father being a loyal man.” As war raged across the country, she carried the quilt across rebel lines and had it signed by scores of generals, statesmen and presidents, totaling 101 autographs in the end.

Soon, the quilt itself became a symbol of solidarity for the Union. “This quilt was saluted by 20,000 troops at the funeral of Pres. Lincoln,” she wrote. “ hung over the East door of the rotunda when Pres Garfield’s body lay in State, has been hung out at different Inaugurations.”

At the time, filling a quilt with the autographs of famous figures was not a typical idea. “There were lots of signature quilts, but they were not quite like this one. Frequently they were in blocks, and a person would do a block, so that would be the equivalent of a page in an album,” says Doris Bowman, curator of textiles at the museum. “A lot of people were writing on quilts at the time, but this one was a bit different.”

Lord wrote that she got the idea following a particularly bloody battle in Tennessee. “After the battle of Stone River, Gen’l Rosencrans suggested I make an autograph quilt of it,” Lord wrote. “At his headquaters his was the first name placed on the flag.” For several years, she traveled the country and covered the quilt with signatures, assigning lesser figures spots on the borders and hexagons and reserving the center flag for men such as Lincoln, James A. Garfield and Ulysses S. Grant.

Detail view of the quilt's center flag, featuring the autographs of Lincoln, Grant, Arthur and others. Photo courtesy American History Museum

What propelled Lord to pursue this quest with such a patriotic fervor? Although details are scarce, it may have been a labor of love. “She had married Henry Lord, but she was only 17 at the time,” Bowman says. “She was interested in someone before that—or he was a very close friend at least—and he was killed early in the war.”

The words Lord put down about her famous quilt late in life bespeak the emotion she would have invested in such an effort. “The various people who have brought it on exhibition have not been very careful of it,” she pointedly wrote. “I have never thought of disposing of it, but having lost my home through fire, I wish to rebuild, and this is the only way I can see to raise money.”

Ultimately, though, Lord was able to hang on to the quilt, and resettled in the D.C. area. “The quilt was never actually sold, but instead passed to her daughter, who brought it to the Smithsonian in 1943,” Bowman says.

Now at the American History Museum, the autograph quilt is not currently on display, but it may viewed it as part of the behind-the-scenes quilt tours conducted the second and fourth Tuesday of every month. A virtual tour of the quilt collection is also available, through which visitors can see Lord’s autographed quilt along with more than 400 others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)